Director

Denis Villeneuve Takes Guillermo del Toro Inside the World of Dune

If making movies is a leap of faith, then Denis Villeneuve’s Dune is a bungee jump. Frank Herbert’s landmark sci-fi fantasia has been considered unfilmable since it was first published in 1965, and the quixotic attempts to adapt it since include Alejandro Jodorowsky’s famously abandoned project (captured in the 2013 documentary Jodorowsky’s Dune) and David Lynch’s notorious 1984 misfire. Then in walked Villeneuve, the French-Canadian master behind brainy, meticulously crafted genre spectacles like Arrival and Blade Runner 2049, determined to tell his version of the battle for the desert planet Arrakis (giant sandworms!), and the messianic figure at the center of it all. Armed with a reported budget of $165 million, technology his predecessors could not fathom, and a starry cast led by Timothée Chalamet and Zendaya, Villeneuve has managed a feat of world-building on a scope that demands the biggest screen possible, while honoring Herbert’s original text.

If anyone knows what it’s like to film the unimaginable, it’s the Oscar-winning director Guillermo del Toro, who had plenty of questions for his friend when the two of them spoke last month. —BEN BARNA

———

DENIS VILLENEUVE: Guillermo, there’s something I have to say. Directors are always intimidated by other directors. They can be competitive. But you are a benevolent giant. I trust you, 100 percent. You’re one of the rare directors that I’ll show a finished movie to.

GUILLERMO del TORO: I know exactly what you mean. I’ve been doing this for 30 years, so I’ve had every experience. Some directors will see the vulnerable parts of your movie, and you can feel that they are not telling you. They don’t want you to make your movie better. But the choices you made since you first showed me the movie are so compelling, and they go past the audience unnoticed. There are certain moments in which you want us to experience the exoticism of the location and the technology with the characters. I was thinking of the attack on the spice plant. You use a very similar lens, and cutting and assembly choices, to the highway tollbooth scene in Sicario,1 or the attack on the bus in Incendies. The distant camera, the jargon on the radio, the cutting to faces. You made it very immediate, and it doesn’t matter if it’s sci-fi or not, you put us there, and that is wise. Did you plan key sequences to be that experiential?

VILLENEUVE: Yes. It’s a key sequence, where you have Paul struggling with his identity, his heritage. And he will strangely find his home in the desert. I was trying to recreate an experience I had myself, of finding yourself in the most strange environment while feeling a deep connection to it. What you felt was exactly the goal, which is that the audience will be in Paul’s feet and experience the discovery of this strange environment. That immersive feeling is one of the things I deeply love about cinema. I think it comes from my youth, when I had the chance to make little documentaries and experimental short films. I was alone with the camera, going through life.

DEL TORO: Some of what you had to Some of what you had to tackle in this film is familiar to me. One thing we had to tackle on Pacific Rim was, how do we do scale? For example, the language of water running over the edges of a ship. Or, the more you make a cloud of smoke complex, the more you are giving scale to the object that’s burning. The camera cannot fit it all in.

VILLENEUVE: There’s something about the fact that the camera cannot grab the world because it’s too big. That was how we approached Dune. There was something about the composition where sometimes things are on the edge of the frame. It’s almost like the cameraman was struggling to capture everything, but it was not possible because the world is so immense. I’m happy you noticed that.

DEL TORO: There are other things, like the way you use long lenses to compress heat signatures on the ground, or the way ships barely make it off the ground. You are building the shots with an “error” that you are creating on purpose. Most directors would choose a sort of David Lean approach, with everything symmetrical and perfect, but you chose not to do that. You chose to build in randomness.

VILLENEUVE: Again, I wanted the movie to be very immersive. And a way to do that would be to feel that there’s a spontaneity, that we are diving with Paul. The camera is just above his shoulder and we’re trying to understand the reality all around him, but things are too complex and too fast and there are too many things to grab onto, and the camera is not able to follow.

DEL TORO: The art direction is very symphonic. Each culture in the film has a different rhythm, but it always feels like one movie.

VILLENEUVE: That was the goal, to create very distinctive cultures with very distinctive forms of architecture and behaviors and needs, but that, in all this disparity, it doesn’t feel like a bunch of different ideas. I have to give a lot of credit to my production designer Patrice Vermette, because that was one of his main concerns.

DEL TORO: One of the moments that was very interesting was the test of fear, 5 in which you come very, very close and you feel it. It’s so smart, this choice to do it through sound. There’s no effect. It’s just pain.

VILLENEUVE: I wanted the movie to be as realistic as possible. My dream was that a scientist could watch it and almost explain it. At the end of the day you’re watching the journey of a man that will be accepted as a messiah. And I love that when you see all his powers, you can explain everything.

DEL TORO: Or disprove them.

VILLENEUVE: For me, god is nature, so I tried to make sure that there were moments that are magical because you want them to be. But you can also explain them from a naturalistic point of view.

DEL TORO: With the worms, the way you chose to show the frequency of vibration on the sand and the rate of sinking under people’s arms and feet is amazing. The animation of the particle effects and the vibration is something that you must have referenced from vibrating sand in a documentary somewhere.

VILLENEUVE: As I was storyboarding, I was thinking that when the worm approached, if such a thing runs under the sand, there will be a physical sensation. And then we started to experiment, and my special effects supervisor came up with this idea of vibrating plates under the sand. So actually, the actors are sinking for real. It’s not visual effects, it’s special effects. And then there was this idea of the vibration on the sand and the shock waves in the sand, which came from studies. My collaborators understood my obsession with nature and physical reality.

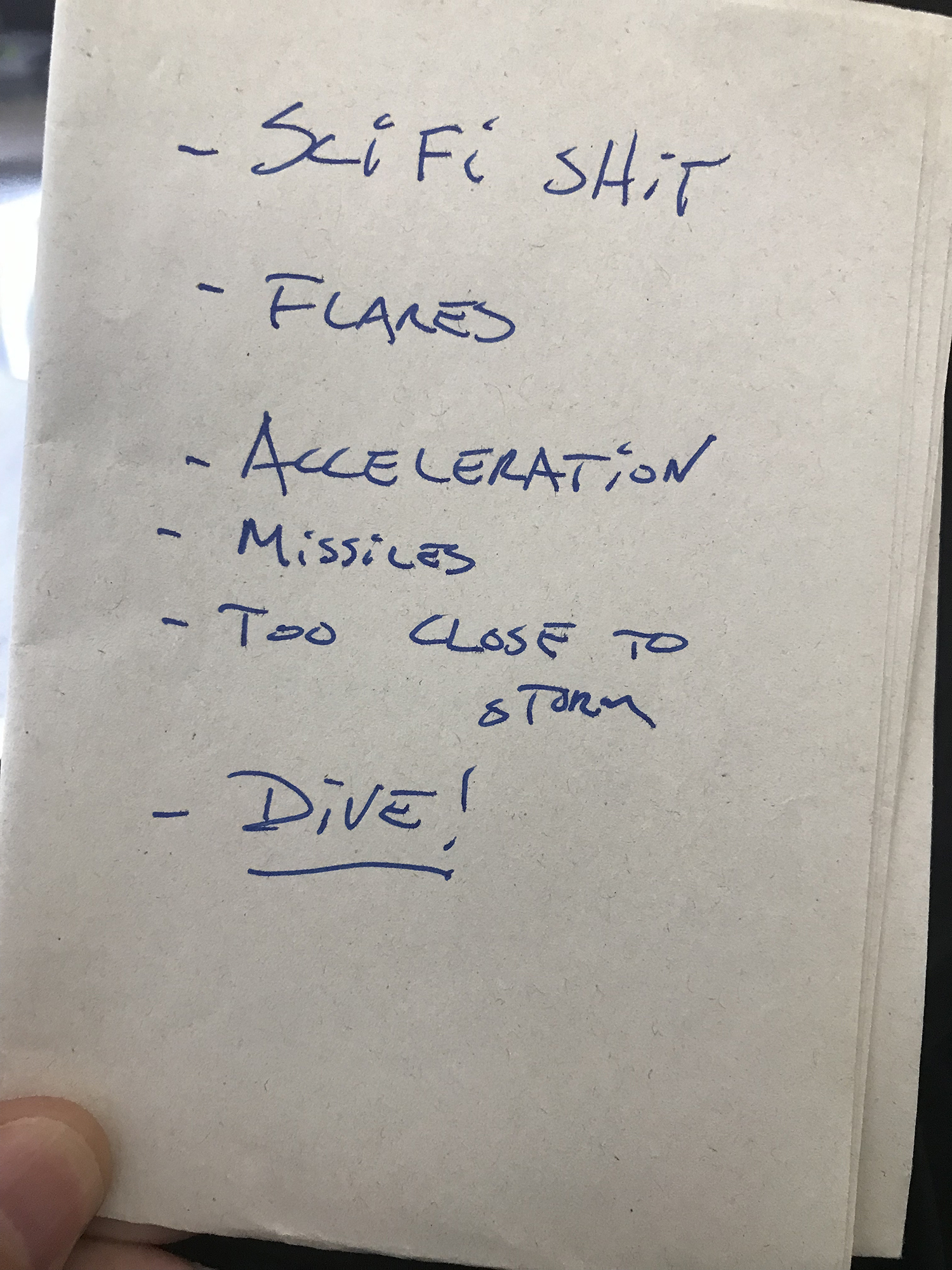

Denis Villeneuve in an ornithopter.

DEL TORO: Your cinematography is interesting to me. The way you expose an image, the darkness is ever so slightly underexposed or over-exposed, creating a milky wash that makes it painterly. And then when we go to the desert, it’s beautiful and brutal and rich. It’s very daring. Sorry that I’m talking rather than asking.

VILLENEUVE: No, no, no, you’re very generous. This is very positive therapy for me.

DEL TORO: I think it’s one of the few movies that has captured the ocean-like movement of the desert. And the way the worm comes in and out, the way that we only see the barbs inside of the mouth, these are decisions. How did you shoot that?

VILLENEUVE: The worm?

DEL TORO: The mouth of the worm.

VILLENEUVE: Frankly, that is all visual effects.

DEL TORO: Oh my god.

VILLENEUVE: It came through a long design process. Then there is a behavioral process. And there were tons of experiments with sand. The work on the sand is something that I don’t think has been done before. They really pushed the envelope in order to make it realistic, because you will believe the worm if the environment around it reacts in the proper way.

DEL TORO: My idea with this interview is to break down your decisions because they are remarkable. When people talk about a big-budget movie, there’s almost an idea that the budget takes care of the movie. I have done movies that cost $1.9 million and $190 million. The bigger the movie, the more complex the decision-making.

VILLENEUVE: Yes. Everything in the frame has to be decided.

Zendaya and crew.

DEL TORO: I’m sorry to come back to your choices, but I will. The way you shot the worm attacking the refinery, there are no silly, artificially dynamic shots. You shoot it from a distance, almost like binoculars spotting the trail on the sand. They’re far away. A bad choice would have been to do a sand-level camera shot of the worm breaking the surface, making it artificially dynamic. You chose not to do that, which is far more daring, because you’re keeping your distance.

VILLENEUVE: It’s more frightening to be far away. The feeling that the thing will get closer to you, but for now it’s far away. To create the effect of distance with the monster coming towards you is something I was obsessed with.

DEL TORO: Can you talk about the lensing of the little hunter-seeker that attacks Paul? It’s very minimalistic and that sequence is very, very tense.

Sardaukar inspection.

VILLENEUVE: There’s nothing more frightening than a spider that doesn’t move. That freaks me out. The hunter-seeker is based on that deep fear of immobility. It’s a bit like in nightmares when you feel like you saw someone in the room, but you aren’t sure they’re there. That was the idea. I love the tension that can be born from immobility.

DEL TORO: How long was your pre-production period?

VILLENEUVE: My memory’s a blur because of the pandemic. It was the longest prep I’ve ever had. On Blade Runner, I suffered because I was finishing Arrival, and it was like, “Never again.” So we had enough time. The key was to start alone with my storyboard artist and then work with a concept artist that I love. What will be the main emotion coming out of the architecture of the landscape, of the light? What will be the look of the movie? I designed the main qualities at the beginning, and then Patrice Vermette came on board and expanded the world. The costume department had to struggle with time because it was a bit last-minute for several reasons. We had to shoot in a very precise box, meaning that I had a lot of money, but not all the money in the world. It was kind of restrictive, and from that came a lot of good ideas.

Cinematographer Greig Fraser and Denis Villeneuve on a location scout in Abu Dhabi.

DEL TORO: I have a saying: “If you have enough money, that means you don’t have enough imagination.”

VILLENEUVE: Exactly!

DEL TORO: When did you discover Dune the novel, and when did you first think, “I could tackle it.”?

VILLENEUVE: I discovered Dune when I was 13 or 14, at the same time I was discovering directing. I was starting to recognize some movies were made differently, specifically those by Steven Spielberg. I discovered François Trufaut, and from there I discovered the French New Wave, and then it was like an explosion of discovery. All the while, Dune stayed in the back of my mind. When people asked me, “What is your dream project?,” the answer was Dune, but in a way it had not been done before. Not in a way that was arrogant or condescending towards David Lynch, because he’s one of the masters. But I felt that when I saw his movie, there were things in it that were absolutely genius, and other things that were too different from the book. It was his take on it, and I didn’t find elements of the book that I loved, the emotions that I was looking for.

DEL TORO: Sometimes when I adapt something, it’s hard to explain to the audience that it’s not an act of arrogance. It’s an act of love.

VILLENEUVE: Exactly. And the fact that David Lynch is untouchable, maybe it was easier. For me, it’s a pure act of love toward the book. It has nothing to do with a comparison.

DEL TORO: Sometimes when a fan says to a filmmaker, “I didn’t like this and this about the way you adapted the book,” the snappy answer is, “Okay. You go do it yourself.” That’s exactly what you did.

VILLENEUVE: I will say that when I first read that Lynch was doing a Dune adaptation, I was deeply, deeply excited. There are a lot of things that I thought were masterful in the movie. But it was not the movie that I had in my mind. It’s not an act of arrogance. I would never dare compare myself to him. It’s more that Dune is part of my life, too.

DEL TORO: They are landmarks on the same landscape. That’s the beauty of making versions. The landscape exists intact between the page and the brain of the reader, and landmarks say, “Hey, how about this?” It’s a beautiful act of sharing and reverence. The best role of the director is to be visible and invisible. I can recognize your signature, but none of it comes from you strutting into the scene and overtaking it. You are serving the movie.

VILLENEUVE: There was a precise moment in my life when I decided I would not make cinema to exist, but rather to communicate or give something. So in a way, I will try to disappear as a director.

DEL TORO: We use movies and stories to vaporize ourselves into the world.

———

Grooming: Maina Militza using Oribe at Folio Agency