Laurie Simmons

When I picked up a camera with a group of other women, I’m not going to say it was a radical act, but we were certainly doing it in some sort of defiance of, or reaction to, a male-dominated world of painting. Laurie Simmons

Laurie Simmons began showing her photographs in New York in the late ’70s: black-and-white, and then candy-colored scenarios with plastic dolls in 1950s-style domestic interiors. In one shot, a woman stands in a kitchen before a table packed with food; in another, a woman sits alone on a couch beside an open newspaper. The work depicts a lonely, befuddled domesticity, a vague sexuality without outlet, and there is an uneasy nostalgia to them.

Since her early days in the SoHo art world, Simmons, who was born in Far Rockaway, New York, has steadily produced ambitious and distinctive photo-based work. She’s continued to craft miniature scenes using iconography from the postwar American culture she grew up in, while bringing in fresh materials—wallpapers, ventriloquist dummies, cut-out bodies from magazines. In 2006, she directed The Music of Regret, a 40-minute film with an old-timey Broadway feel that includes songs (she wrote the lyrics), dancing dummies, feuding neighbors made of repainted rubber craft puppets from the ’60s—even a bewigged Meryl Streep. Simmons has also returned, on various occasions, to an image that has become one of her signatures—her “object-on-legs,” which began in 1987 with the Man Ray-esque Walking Camera I (Jimmy the Camera), in which a vintage camera she borrowed from the Museum of the Moving Image appears perched on the shapely, white-stockinged legs of a friend. From there, she put legs on a tomato, a house, a purse, a clock, a cake, a gun, and more. There’s an unmistakable feminist perspective to the work, a suspicion of gender roles and the narrow, immature, child-like lives and psyches they promote.

Simmons, now 64, is married to the painter Carroll Dunham, and together they have two kids, Lena and Grace. It’s a family of artists. Grace is a poet. Lena is Lena Dunham, who cast Simmons in her breakthrough feature, 2010’s Tiny Furniture, as Siri, an artist who photographs doll furniture and brittle mother to Dunham’s lost, post-collegiate character. Simmons has said that it took some work for her to get the role right. In real life, Simmons is anything but brittle—she is engaging, curious, and warm.

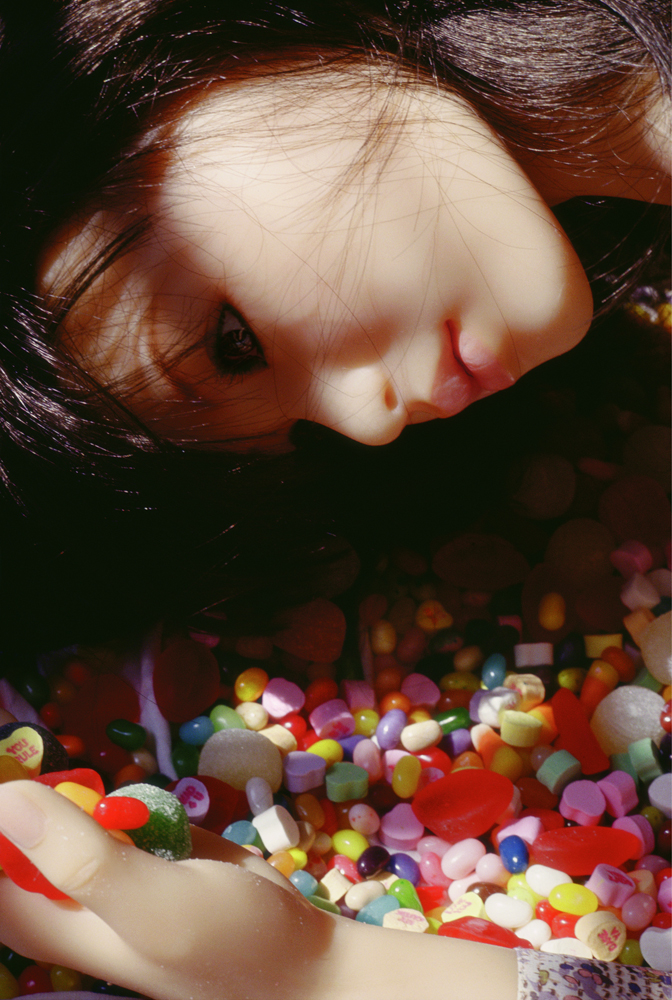

A new period of her work began in 2009, on a trip to Japan with Grace. Simmons entered a shop where she encountered a “love doll”—a life-sized, realistic-looking female mannequin, which men buy as a sexual aide and perhaps for companionship. (The doll comes with an engagement ring and a vagina, packed together in a separate box). She ordered one, then a second one, and shot them in various poses and costumes in her Connecticut home, ultimately dressing them as geishas. The Love Doll photographs are arguably the most striking of her career. The series reveals the burgeoning relationship between photographer and subject, and narrates the doll’s cautious discovery of her new life. A deep vulnerability that was captured in her early work has returned, matched by her seemingly infinite facility with the dolls.

More recently, she has been inspired by Japanese kigurumi culture, in which men and women go out in public dressed as life-size dolls. In one image, a female body dressed in red latex bondage gear, a huge, anime-style mask, and long, crayon-blue wig sits on a chair near a window. The figure seems neither human nor doll.

As Simmons was waiting for the last of her kigurumi masks to arrive from Russia, in preparation for her upcoming show of photographs at New York’s Salon 94 in March, we spoke over the phone, she in New York, I in Toronto.

SHEILA HETI: I love your Love Doll pictures. And I had a really weird reaction to them. I felt the way I sometimes feel looking at pictures of beautiful women in magazines, where I have a sort of desire to be them. It was impossible to keep it in my head that they were dolls, because there’s so much emotion in the faces—I kept having to remind myself: This is not a person.

LAURIE SIMMONS: You know, I’ve been working in my studio with a new assistant who I just adore, and she said, “I can’t believe that you turn the doll just a fraction of an inch, and the expression changes.” I said, “Well, that’s the spécialité de la maison—the house special. I’ve been doing it for over 30 years.” The challenge has always been to wrest emotion out of a face that we think of as only having one emotion. It’s moving a light, moving my camera; it’s just this mental investment that I make, and suddenly, everything changes. Parenthetically, I have to say, I don’t particularly like dolls, nor have I ever liked them. That’s something I really wanted to get out there right away. [both laugh]

HETI: No, it doesn’t seem like it. It seems like they’re a tool. It’s not that you’re obsessed with dolls any more than a painter’s obsessed with paintbrushes.

SIMMONS: I’m really happy to hear you say that because, you know, for every time someone says that, there are a thousand people who say, “My mother has this amazing doll collection I want you to see,” and I’m like, “Oh no, no. God save me!”

HETI: I want to talk about your Geisha Song video [2010], where you shoot the love doll dressed as a geisha, the camera sort of circling around her as she sits very still. And you can see how the back of the doll’s head fastens, and you can see these little bumps on the skin that show that it’s manufactured. When I saw this video, suddenly the dollness of the doll came back. You don’t see any of those giveaways in the pictures. Did you make the video partly to reveal the very thing you tried to conceal in the photographs?

SIMMONS: No, and I was sort of upset at first, because I had a makeup artist work on the geisha makeup for hours, and there were some imperfections and dust in the studio, and under the scrutiny of the HD lens, you could see everything. So I thought about it and I talked about it with my husband, who’s basically my brain trust, and I just decided that this was the moment to let it be, that I couldn’t really fight it. And ultimately it became beautiful to me because I always edit out, you know, the coffee cans that hold up the set. I’ve always gone for a kind of perfection. So it was a big moment to see all that, let’s call it schmutz, on her face, and let it go. I’m stunned you noticed it.

HETI: Well, it struck me, because it took away the feeling of, “Oh, if only I was that doll.”

SIMMONS: But in the end, it’s so much better to get the feeling of, “Wow, she’s so perfect,” from a doll than to have to bear that from a woman in a magazine.

HETI: But it wasn’t only her beauty I was responding to. My desire to be her also had to do with the innocence you imbued her with. I don’t think in my whole life I’ve ever felt envy for a creature because they’re innocent, but that’s what I felt looking at those pictures.

SIMMONS: I always try so hard to find a male doll and shoot a male doll, and it always kind of implodes. Whenever I use men, they’re so scary and so dark, and I can never find this sort of lightness or this place between doll and human that I find with female dolls.

HETI: You’ve said that you wanted your photographs to be “dumb-looking.” I love that so much. I wonder where that came from.

SIMMONS: I think from the fact that my father gave me my first Brownie camera when I was 6 or 7. My father had a camera too. We would just go out in the backyard and he would tell us to stand there, and we would end up being a figure in the center of the picture. Like, there’s my sister in a party dress. There I am with a runny nose. It was the dumbest sort of framing job you’ve ever seen in terms of the conventions of picture-making, and I loved that. I thought, “Do I really have to do any more than that?” So in my early pictures of dolls and dollhouses and toy cowboys, I just stuck them in the middle of the picture.

HETI: It’s so confident, for one thing.

SIMMONS: I do remember at my very first opening in 1979 another artist coming up to me, and he was haranguing me, saying, “Did you really intend for these things to be so dumb? You just put it there and took a picture of it.” He wouldn’t let it go. So that’s what made me think about the dumbness aspect more.

HETI: There’s something else you said—that you didn’t want to go out into the streets, you wanted to work in your own home. I always feel like that too. I tried to get a studio and I couldn’t work there.

SIMMONS: I’ve tried that “get a studio” thing. It just doesn’t work.

HETI: All the emotions are in your house. How can you work so far from your feelings?

The first scene in Girls always cracks me up because Lena was never cut off that way, but my parents cut me off. I was the no-more-money girl. I think Lena probably borrowed heavily from my ‘real girl’ struggles as a young artist in New York.Laurie Simmons

SIMMONS: Right. I mean, a few times, like when I shot underwater [Water Ballet series, 1980-81], I obviously had to go to swimming pools. But then after that, I started dropping little toys in tanks of water in my own house. There are times when I really need to go somewhere to shoot, but it never feels right. And I never wanted to be that person who I would see out on the street with their cameras, and they looked really strong and cool and tough, but I just kept thinking, “I’m not that person.” It felt like the actual act of shooting was a kind of performance.

HETI: That’s why I hate cafés. I could never write in a café.

SIMMONS: Right, we didn’t want to be that caricature of who we are. I love acting. I can’t believe how fun it is and how in-the-zone I am when I’m doing it. But I didn’t want to be an actor out there with my camera. Even after all this time, I think I’m still, in many ways, a terribly self-conscious person. I’d probably be shooting and think, “Well, how does my hair look?”

HETI: Is that part of why you’ve said that glamour, for you, is getting prepared for the party; it’s not being at the party?

SIMMONS: I think so. When you’re getting ready, you finally reach a point where your clothes are right and your hair and makeup are right, and you’re not comparing yourself to anyone. It’s a really great moment. Then you get to the party and it’s like, “Oh my god, I’m wearing the wrong thing! I’m garish!” or “I’m underdressed!” Of course, when I had kids, I would get dressed to go to the party and I would come out and they would say, “Mommy, you look so beautiful!” And it was all downhill from there. [both laugh] But I have to take a break and ask you: What about a little mermaid in a bottle who lives in her own shit and vomit?

HETI: I remember where I was when I wrote that story, “Mermaid in a Jar.” I was at a boyfriend’s, and he was the only boy I ever dated who was rich, and his parents had a ski chalet, and I just didn’t know how to break up with him, so I decided I would be celibate.

SIMMONS: That’s a good way. Unless he decided to be celibate too, and then you’d be perfect for each other.

HETI: We went to his ski chalet and he was kind of, like, a pot smoker and a drinker, you know, one of those wealthy kids who doesn’t know how to live because he’s probably intimidated by his father’s success and didn’t have to work. So he had just blown up at me for my celibacy, and I was in this horrible place and feeling so trapped, and I wrote that story.

SIMMONS: What I really love about the story is this almost little-girl fantasy quality colliding with real-world stuff. That’s something I really identify with.

HETI: I don’t know if you feel this way too, but I think there’s a kind of connection between the first work you do and the imagination you had when you were a child.

SIMMONS: That’s a lot of what I’m thinking about now, because I feel like I spent so much time trying to understand my identity and my identity as an artist. But when all is said and done, at this age, I feel the most like I felt when I was 11. And all those talents I had when I was 11 and 12—I’m letting them sort of happen again. So it seems, in some weird way, that—I can’t speak for men, but for women—we go back to a kind of pre-adolescent state when we were superfree and supercool.

HETI: I just got shivers all over my body. Did you know that Simone de Beauvoir says the same thing in The Second Sex? Women, post-menopause, go back to how they were before they started menstruating, and there’s this great freedom in a woman’s life when she reaches the end of that reproductive cycle, and that most women come into their own strength, the same strength they had as a girl.

SIMMONS: That’s amazing. I remember years ago hearing a gynecologist say, “Women report a great sense of calm and well-being post-menopause.” This was way before I was even thinking about it, but I thought, “Hmm, that might be something to look forward to. A sense of well-being!”

HETI: That’s part of the reason I decided to be celibate at that time. I just had read The Second Sex, and I was like, “I wonder if I can bring this on artificially,” the power I had when I was 11, or that confidence.

SIMMONS: Yeah, but I think the big news there—and we’re gonna go way off-topic—but most post-menopausal women I know are not celibate. But let’s have another interview for a medical magazine. [both laugh]

HETI: By the way, I couldn’t believe you made the Kaleidoscope House [series, 2000-02]. That is such an iconic thing from my childhood, not that I had one …

SIMMONS: Yeah, it’s a cool thing. I made a toy so I would have another prop, to be totally honest. It seemed like two worlds were colliding, with a big advantage for me. Also I thought, the daughters might like to play with it. So I made a doll that was Lena, and a doll that was Grace, and the cat in it was our cat.

HETI: Your parents weren’t artists, were they?

SIMMONS: No, my father was a dentist. And my mother was a—do we still say “housewife”? A home engineer. [laughs] I came to New York in 1973, and it’s funny. The first scene in Girls always cracks me up because Lena was never cut off that way, but my parents cut me off. I was the no-more-money girl. I think Lena probably borrowed heavily from my “real girl” struggles as a young artist in New York.

HETI: Do you think you and your husband passed on stuff about navigating the art world to Lena and Grace?

SIMMONS: I think they were very aware of the highs and the lows. It was impossible to hide the periods when there was extreme belt-tightening, because there were things we had to do, like sublet our house and move to a smaller place, or figure out a new way to live. Then there were also moments of, you know, you have an exhibition: no sale, no reviews. It’s hard not to get blue, and I think the kids were very aware of those periods. So if there’s anything they’ve picked up, it’s a kind of resiliency. That seems like a pretty good legacy.

HETI: Did you see a lot of people drop out?

SIMMONS: Oh, my drop-out list is long. I think about it so much, because there’s a kind of last-man-standing feeling. The thing I wondered about so much as a young artist, particularly when things weren’t going well and I was really struggling, was, “Will I know when to give up? Will I know when I’ve suffered enough rejection? Will I know when to get out?” But from my vantage now, I think it’s kind of what you have to do, why would you ever stop?

HETI: The thing I worry about is, what happens when your talent flees? Because you see that with writers sometimes, they start writing these awful books. And there’s something sort of horrifying about it.

SIMMONS: I think it might go away for a while, but then I really believe it could come back. It’s a series of peaks and valleys, like anything else.

HETI: In your marriage, do you have a feeling of being soul mates on an artistic level?

SIMMONS: Yes.

HETI: How does it work?

SIMMONS: It works really well. Our so-called “pillow talk” is so much about what we do. Not the specifics of how we make our work or what happened in the studio today as much as what it’s like to move your work from your mind to the studio to the world and, like, what exactly are we doing being artists in the 21st century?

HETI: What do you think is the main thing about being an artist in the 21st century?

SIMMONS: Well, I teach a graduate photo seminar at Yale, and I sometimes feel so overwhelmed by the task the students set before themselves to be artists, because—it seems so quaint, but when I picked up a camera with a group of other women, I’m not gonna say it was a radical act, but we were certainly doing it in some sort of defiance of, or reaction to, a male-dominated world of painting. This was before the internet, before photographs on Instagram and online in magazines and newspapers. It’s just, how do you proceed? How do you find a place for yourself as an artist? The visual world has blown up, the world of writing has blown up; there’s so much text online. Anyone and everyone can express themselves. It’s a lot to think about as an artist. Also, that the persona of the artist might actually be of some importance. When I came of age, it was important to be quiet and hang back and be mysterious. I knew artists who didn’t even want to show up at their own openings. They never wanted to have their picture taken, didn’t want to autograph a book, didn’t want to answer a question. I came of age in a world where it was “Let the work speak for itself.”

HETI: When I was a teenager, I would read Dostoyevsky or I would read Tolstoy, and I’d never read an interview with Dostoyevsky. I had seen, maybe, a line drawing of his face, which made no impression on me. That’s the world I thought I would grow up into as a writer. And it’s not at all like that anymore. If somebody asks me to do an interview, part of me says yes in my mind and part of me says no, because I still have that romantic idea of the artist as somebody who you know through their work and that’s it. Warhol is who I think of when I think of someone who really used the persona of the artist in an interesting way.

SIMMONS: It’s hard to remember, but when I first came to New York, in the ’70s, artists were certainly divided about the Warhol persona, and about the work. I thought it was utterly cool—I thought the Factory was utterly glamorous—but there were a lot of artists I really admired and respected who were older that kind of dismissed it, couldn’t get it, and felt that there was a lack of seriousness about it. Hard to imagine now.

HETI: Can you tell me about your latest work?

SIMMONS: It’s inspired by these people called “dollers.” They perform kigurumi—it comes from Japan, but it’s a worldwide thing. They walk around in doll costumes publicly.

HETI: How do you cast the photos?

SIMMONS: I use people that are close to me, like a studio assistant or a friend, someone I know who’s going to really enjoy it. It’s important to me to have men inside there, too, because so many dollers are men. It’s putting me into a pretty odd headspace, the shooting, because I understand the motivation of these dollers to dress up. There’s a way that you start to prefer the reality of that world to your own world. It’s so much more beautiful. And the characters become really real to me, like, scarily real, so that when my studio assistant takes her mask off, I’m really disappointed that Danielle is no longer her character.

HETI: It’s such a great metaphor. Because in real life, with the people one knows—there’s the person you see and have access to, and then there’s the private person inside that person. These dolls are the same thing. There’s a person inside the person.

SIMMONS: I feel like I’ve finally got to this place that I really want to be. The place where, in my fantasy, the characters just get up and walk around—this interstitial place between humans and dolls. But I also feel like, where am I supposed to go from here? Because this feels like the place I’ve always wanted to be, for my whole life of shooting.

SHEILA HETI, A TORONTO-BASED WRITER, IS THE AUTHOR OF FIVE BOOKS.