Glenn Ligon

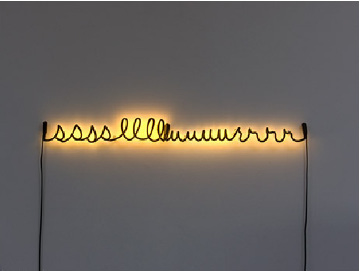

In so many ways, Glenn Ligon’s art productionsare like illuminated manuscripts. The 49-year-old Bronx-born artist is probably most famous for his text paintings, which he’s made since the ’80s, appropriating words by everyone from Zora Neale Hurston and Ralph Ellison toRichard Pryor. Sometimes a line floats in the center of the canvas, and other times it repeats manically from top to bottom, covered over in paint until it’s almost aggressively illegible. Such sentences that flicker in and out of abstraction include: I do not always feel colored and Iwas a nigger for twenty-three years.

I gave that shit up. No Room for advancement. Clearly, Ligon relies heavily on the legacy of writers, but he also actively engages with the history of abstract painting. In other pieces, however, he takes that fight between readability and revolt away from the canvas and the oils—particularly in a number of neon works, where the white neon bar is covered over in black, giving the simultaneous sense of illumination and blackout. Recently, the artist even entered the film business. His piece The Death of Tom is an abstractionist restaging of the last scene in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the silent movie filmed by Thomas Edison’s studio in 1903. Ligon asked experimental jazz musician Jason Moran to create the soundtrack for the film—“playing to the shadows,” as the young musician puts it. Here, the two talk about the importance of learning things that aren’t always written down.

Jason Moran: When did you figure out that art—with a big “A”—was an option for a lifestyle, versus, say, working for ups?

Glenn Ligon: You know, it took a long time to figure that out, because there wasn’t any precedent in my family for being an artist. Although, ironically, when my mother was younger, she wanted to be a singer, which I found odd because I never thought she had a good voice. [both laugh] But at some point she must have had a good voice. I remember seeing pictures of her from the ’40s, when she’d just gotten married. She was very glamorous, very stylish, and being a singer once must have been a possibility for her. When I started showing artistic talent at a very young age, she was encouraging.

Moran: What was your artistic talent?

Ligon: Drawing, mostly. But I also had a deep interest in literature, which became a big part of what my work is about. But back then I was just filling up notebooks with sketches and drawings. So my mother sent me to pottery classes after school. At this point she had separated from my father. My brother and I were going to private school on scholarship. There wasn’t a lot of extra money, but there was an attitude that money could be spent for anything that bettered us—in that black, working-class, striving kind of way. Culture was betterment. Anything we wanted to read was fine. Pottery classes or trips to the Met were fine. Hundred-dollar sneakers? No.

Moran: What year are we talking about?

Ligon: We’re talking about the late ’60s and early ’70s in New York. But, as I said, my mother really didn’t come from artists. Her famous quote to me was, “The only artists I’ve ever heard of are dead.” The pottery classes were meant to be a part of my overall uplift. I knew what it meant to be sent to art classes, but I still didn’t know anything about being an artist. I graduated from Wesleyan University with a b.a. in art. I was really headed toward an architecture degree, but when I did the requirements for the major, I realized I was more interested in how people live in buildings than in making buildings. I was more interested in the interactions that happened inside the structures. So I got an art degree as a default position. When I got out of school, I went to work proofreading for a law firm. That became the thing that I told my mother I was doing—proofreading—because that was understandable. I had a job.

Moran: After college you lived in the city?

Ligon: Yeah, I lived in Fort Greene, Brooklyn, painting on the weekends and at night, and working at the law firm during the day. Then I switched up so that I could work 12-hour shifts at the firm on the weekends so I could have days free to paint. But it was almost like I had a secret life, because I wasn’t showing any of my work. It was just in my house. In ’89, I got a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. That’s when I started to get into group shows. Suddenly I sort of “came out” as an artist

[laughs] . . . I said to myself, “If the government thinks I’m an artist, I must be one.”

Moran: That was when they still gave individual grants.

Ligon: Yes. And they learned their lesson. [both laugh] They don’t trust artists anymore. Now the money has to go through arts organizations. But, yeah, back then you could get a grant, and I got $5,000—a huge amount of money. It was a turning point for me because I could either keep working at the law firm or I could cut back and think about how to become an artist rather than just make art, you know?

Moran: What was the kind of work you were doing in the ’80s? Was it text or figurative?

Ligon: I was still trying to figure out how to be an abstract painter, really. Painting was my first love, and I was interested in abstract painters like [Willem] de Kooning, [Franz] Kline, and [Jackson] Pollock. They were my first heroes. But around 1985, I was in the Whitney Museum independent study program and they kind of pooh-poohed painting. Painting was the enemy. The program consisted of a very long reading list and discussions of what we read. It was an introduction for me to how theoretical models from other disciplines were being applied to art. I was still interested in painting, although it wasn’t encouraged there, and it took me a few years to figure out that I wanted to continue to do it. But the Whitney program was when I started to put text into my work, in part because the addition of text literally gave content to the abstract painting that I was doing—which isn’t to say that abstract painting has no content, but my paintings seemed content-free. At some point I realized that the text was the painting and that everything else was extraneous. The painting became the act of writing a text on a canvas, but in all my work, text turns into abstraction.

Moran: Right. It’s like jazz musicians like [John] Coltrane—not that he doesn’t play content, but he plays a different kind of content. You get a vibe from his music, but he also gave very clear titles for these abstract pieces. I think some of my frustration was that I didn’t think I was a good enough of a musician to be able to just play something that someone would understand on a gut level. That led me to do what I do sometimes with voices—to sample them or bring that content into the music.

Ligon: I remember I once did these text paintings that consisted of single, repeated sentences from Zora Neale Hurston. At a lecture, a guy said to me, “You know, when I look at your work, I don’t know what I’m looking at, but when I look at a de Kooning painting, I know what that is.” I said, “Well, the paintings I’m doing have a very legible sentence at the top of the canvas.” [laughs] I think what he meant was, “I don’t understand—or want to understand—your content. I understand abstraction, but I don’t understand these words.” I had to point out to him that de Kooning paintings are a language to be learned. When they were first shown, they were ridiculed as being just drips and splatters and splashes. You had to learn how to read them. I’m only asking that the same process happen with my work. But I’m fascinated by what you were talking about, how jazz musicians like Coltrane needed these very clear titles for their abstract music, and your decision to bring voices into your music as a way to tap into content. It’s related to the way my text-based work still functions as abstraction for me. If I repeat a sentence down a canvas, the text starts to smudge and disappear. It essentially becomes an abstract piece. The meaning of the text is still there . . .

Moran: Someone once told me that some writers go through their favorite works and type out a sentence or a paragraph just to feel the rhythm of that writing.

Ligon: It’s a great idea: to feel the rhythm of something by seeing how it flows on a page.

Moran: That’s the immediate process of how most jazz musicians learn how to play. Ninety percent of the stuff isn’t written down. Most of it is improvised. You really have to listen and figure out, how did Thelonious Monk play this? Or, how did Duke Ellington get that tone from this chord? You have to sit for hours just listening to people play, and then try to repeat what they were playing so you can build up your own language.

Ligon: What drew me to your work was when I heard you playing Monk. I heard Jason Moran playing Monk—I didn’t hear someone trying to re-create Monk in a straightforward, note-for-note, this-is-how-he-would’ve-done-it way. I realize that it’s the result of an incredibly intense research project. You figure out how he played as the base, and then you build your own vocabulary up

Moran: For me, Monk is the best example. When he plays someone else’s work, it just sounds like him. I discovered Monk in the ’80s, right around the time of the documentary Straight, No Chaser [1988]. I was like 13, so I’m not thinking about how he was misunderstood in the ’50s. I don’t know about his history or baggage or what he overcame. He had his eyes set and he never wavered, and I thought, That’s how you’re supposed to do it—period. When I try to approach Monk’s work, I have to make sure that I have reckless abandon within it. I try to make sure I don’t let that sand castle just stand. It should start getting demolished from the bottom and move its way up to the top, dissolving into something else. I think that’s the problem with jazz in general. It’s still a young art form—a little over 100 years old now—and there’s the idea like, Shit, we’ve only had a couple of golden eras, and we really want to keep looking back at them. That will just get us stuck.

Ligon: I love Monk’s song “Just a Gigolo.” It’s probably a minor song for him, but whenever I hear a recording of him playing it, I’m mesmerized, because Monk clearly loved pop music. He took it very seriously and made an amazing thing out of it. Jason, I remember seeing you in concert about a year ago where you played a recording of lyrics by Ghostface [Killah] of the Wu-Tang Clan—while on the piano, you played the music from a runaway-slave song. It was an incredible mash-up of different historical moments.

Moran: When I talk to students about playing those old standards, like “Just a Gigolo,” I say, “That song has been played far better by another musician, so you can either try to outdo that musician or try to play like them. Or you can take a deconstructionist standpoint.” Music reads from left to right, from top to bottom. Why haven’t you read it backwards? Read it vertically. Just cut out what you need—literally—and throw the rest away. See what that sounds like and what it spawns. With Wu-Tang, I just hadn’t heard them addressed properly. It should still have its vulgarity. Fucking hip-hop is vulgar. So Ghostface has this song called “Run.” I don’t know what it is about rappers, but as lyricists they feel like someone is always assaulting them—they tend to talk about this paranoia a lot. In the song “Run,” he’s running, and I feel like it’s a cop that’s chasing him. I thought, Well, this is the same shit as “Run, Nigger, Run,” the old slave song. It’s the same concept. It’s the same feeling. So I wanted to put those together to see if they worked. I wanted the audience to contemplate whether that connection worked. I really use the stage as a testing ground. Most people work at home and bring in the result. Fuck that. Let’s cut to the chase. I want to test it in front of people who have their notions of what a song is or isn’t. It’s a matter of working.

Ligon: I think there’s an interest right now in the performance aspect of artworks, instead of just hanging things on walls. We’re in a moment when a lot of younger artists are looking at work from the ’60s and ’70s—they are looking at the pieces by Marina Abramovic or Vito Acconci. These pieces have a time element. They were performed live. To perform them again now isn’t simply an homage, because it’s a different audience, a different moment. I worked on a film project called The Death of Tom, because I was interested in performance, and also I wanted a different way of using text. The film was based on a novel—Uncle Tom’s Cabin—but it was meant to be a re-creation of the last minute of Thomas Edison’s silent-film version from 1903. I play Uncle Tom. [laughs] It’s funny. It’s one of those situations where you think you have a great idea and then you’re embarrassed by it. I worked with a cinematographer to shoot it exactly the way Edison’s cinematographer did—on a hand-cranked camera, black-and-white, 16 millimeter, with a double exposure. There’s a moment where little Eva comes down from heaven to visit Tom. When we cast the parts, there was never a moment where

I wasn’t sure I should play Tom. Of course, when I saw the video footage, I thought, Oh, my god, this is the most embarrassing thing I’ve ever done in my life. After we shot the film and had it processed, we found out that it hadn’t been loaded properly in the camera. The film was just blurry, fluttery, burnt-out black-and-white images, all light and shadows. But I thought that failure of representation was in line with my larger artistic project, which has always been about turning something legible like a text into an abstraction. And then I realized that the Edison film would have had a piano accompaniment when shown in theaters. That’s when I thought I should bring you into the project. I was very surprised how narrative the film became by the way you played over it.

Moran: I was somewhere in Europe when you mailed me a dvd of the film and video documentation of the shoot. I remember watching mostly the video footage and then seeing that last piece—which became the whole piece—which was the blurriness. I thought, Let’s see what it would be like if I only played to the failed footage. There’s an Art Blakey saying that goes something like, “When you play something wrong, play it loud.” That way, you really commit to your mistake. I remember I was in Oslo at a sound check. I told the sound engineer to just press record, and I watched the footage a couple of times and played to the shadows. And then I couldn’t believe it when you wrote back saying you weren’t going to use any of the other footage, just the failed footage.

Ligon: That’s because the score was so good! In the end, what you see when you watch the film is all the dress rehearsals and various takes of Tom’s death, repeated over and over again. But the way you play to those repeating scenes gives it so much drama and narrative.

Moran: Luckily, I got to see the piece at your show at Thomas Dane Gallery in London this past spring. I was talking to people afterward, and the filmmaker Isaac Julien said that your entire show was kind of the first post-election show. And The Death of Tom is like the quintessential post-election piece. It really tries to close the door on a part of an African-American experience that had its time and its use. But hearing Isaac say that really made it clear how important that show was. There was also your big black neon piece that says the word America. You told me how it flickers slowly on and off.

Ligon: Yeah, every a couple of hours it goes off, and then on again. The irony about that piece is that it is actually based on Dickens’s novel A Tale of Two Cities. And really the genesis of that piece was when the U.S. first went into Iraq and Afghanistan. I remember seeing a picture a couple of years ago of a little Afghani kid, no more than 13, standing outside the ruins of his house that had been mistakenly bombed by Americans, and several members of his family had been killed. He was bemoaning these unjust killings and cursing America, but also saying that America needs to live up to its promise. I thought, “This is an amazing moment. You’re standing in the ruins of your house, with members of your family still buried in the rubble, and you say, ‘I believe in America,’ because America has the ideals that it does not live up to, instead of just saying, ‘Fuck you all. I’m gonna strap on the bomb, and I’m comin’ for you.’ ” But there is this sense that America, for all its dark deeds, is still this shining light. That’s how the piece came about, because I was thinking about Dickens’s “the best of times, the worst of times.” Yes, that’s where America is. We can elect Barack Obama, and we’re still torturing people in prisons in Cuba. Those things are going on at the same time. Of course, because the piece is a black covering over white neon, it gets read as black America/white America, and those kind of binaries, which is a part of it. I’m not denying that. But I think that maybe if the piece has a kind of richness, it is because of the ambiguity.

Moran: What books are key reading for a viewer who is looking at what you have done?

Ligon: A key text for me is [James] Baldwin’s essays. And, in particular, his essay Stranger in the Village. It’s a text that I’ve used in a lot of paintings. The essay is from the mid-’50s, when he’s moved to Switzerland to work on a novel, and he finds himself the only black man living in a tiny Swiss village. The essay is about the fascination and fear that the villagers approach him with. He even says, “They don’t believe I’m American—black people come from Africa.” The essay is not only about race relations, but about what it means to be a stranger anywhere. How does one break down the barrier between people? It’s a global question and it probably reflects what I’ve been trying to do—reach out more.

Moran: Do you think you’ve succeeded?

Ligon: I think now that I’ve gotten older I’m much more interested in what you were talking about before, thinking about how do you experiment in public? How do you let an audience in on this process of learning about something?

Moran: That was the thing that attracted me to conceptual art. It wasn’t as if it were all explained, but it shows the steps—starting with the open sides of a cube. The process becomes part of the piece. Just like me listening to Bach on my headphones and trying to play along. Or the whole band with headphones . . .

Ligon: And you actually do that onstage. You come out with your headphones on listening to something.

Moran: Yes, there is something intrinsic to it, like it’s of the moment. The part in my concert [In My Mind: Monk at Town Hall 1959] where everyone puts on headphones was my attempt at interaction without actual interaction with each other. Everyone is just interacting with the one song that each one is listening to, and that group interaction, we never actually hear. Jazz is always about listening to everything that’s happening, and responding, but for this piece, we play something on our instruments that we can’t even hear because the headphones are turned up so loud.

Ligon: The musicians must have had to really trust you because that seems a little counterintuitive. [laughs]

Moran: Yes, and a few people took their headphones off to listen and found that they were gravitating toward the same rhythms and sounds. It’s interesting to think what effect the music that I make can have. I have no idea what people are doing with it. Or the work that you make—you have no idea how it is affecting people.

Ligon: Right.

Moran: When you make a work and you put it out, and then people eat that up and they digest it a certain way, you have no idea what their bowel movement’s gonna be. [both laugh] How they use it, what nutrients they pull, and what waste they leave . . . That becomes so interesting. I mean, we’re in New York City, man. This is what I tell my students. In music school, they don’t tell you to go spend time in museums. They never tell you to go see dance. And those are forms that use music so much. There’s a whole other living I’ve created working with visual artists—not just dealing with me and a piano going to a solo performance. You know, like I wish I could take one of Bruce Nauman’s crazy clown scenes and put music to it. I’ll never forget in the mid-’90s going to see the Nauman show at moma. It looked like some strange circus. And being able to hear things that were happening in another gallery, it was a real stretch of the imagination.

Ligon: I saw that Nauman show, too, and I think it was the first time that I realized that a certain kind of performance work could be scary. [laughs] Sol LeWitt had a huge influence on my work because of his use of repetition and his clarity, setting up a system and letting that system go. That’s kind of where the text paintings came from. But when you look at Nauman, you realize this is some scary inside-your-head stuff, that art can also be a window to one’s unconscious.

Jason Moran is a New York–based jazz musician, composer, and recording artist