IN CONVERSATION

Nick Cave and Jenny Holzer Wrestle With Legacy at the Obama Presidential Center

Nick Cave on the construction site of the Obama Presidential Center Museum. Photo courtesy of Nick Cave.

When Nick Cave and Jenny Holzer got together to talk about their forthcoming commissions for the new Obama Presidential Center, they admitted to feeling a little sheepish. “Who wants to make crummy art?” Holzer pondered. “Who wants to make crummy art in a Presidential Center for a president one admires?” It’s an understandable anxiety. The Obama Foundation’s new art initiative is no small feat. A series of 25+ site-specific works will populate the Chicago campus dedicated to the legacy of America’s 44th president. For Holzer, that means a text-based painting sourced from declassified FBI files on civil rights activists, including the Freedom Riders, whose courage and endurance she sought to memorialize. And for Cave, working in collaboration with Seneca artist Marie Watt, it’s This Land, Shared Sky, a monumental wall relief that fuses beadwork, jingle clouds, and layered fabric to reflect on migration, belonging, and the shared histories embedded in a land meant to stand for opportunity. The two artists, each gifted at infusing beauty with social charge, now find themselves wondering whether art can ever feel worthy of the moment. Last month, Cave and Holzer gave themselves a breather to reflect on representation, relief, and a nation in disarray.—EMILY SANDSTROM

———

JENNY HOLZER: Hi, Nick. Good to talk again.

NICK CAVE: Hey. How are you?

HOLZER: I’m faceless. I hate looking at myself.

CAVE: Well, so do I. Can I get rid of my face? [Laughs]

HOLZER: I like your face. I just don’t like mine. [Laughs]

CAVE: Oh, my goodness. Trust me, I get it.

HOLZER: So should we torment one another with questions, or solutions? Or jokes?

CAVE: Both. I was at the No Kings Rally here in Chicago, which was amazing.

HOLZER: Good work.

CAVE: Sometimes you just feel so isolated from everything, so it was nice to jump on the train and go downtown and be in the midst of all of it.

HOLZER: I salute you, sir.

CAVE: Yeah. But I’m interested in your piece that you’re doing for the Obama Presidential Center with the Freedom Riders. Is this a painting?

HOLZER: I tried to be a painter when I was twenty-something and I failed miserably. So fifty-some years later there’s some improvement. I rely heavily on content to get me by, and for this piece, I went to formerly secret documents. One was about the courageous and effective Freedom Riders, so we stuck with that and we’re trying to finish it to make it good enough.

CAVE: Well, it looks great so far. I know what you mean by trying to make it presentable. We’re in the midst of that as well. I’m collaborating with Marie Watt, and collaboration is interesting in itself.

HOLZER: What started you on your piece? What was the spark?

CAVE: I just started one day in the studio. I was singing the song “This Land is Your Land,” and talking to Marie [Watt]. We’re creating this wall relief that’s about 12 feet by 40, and so I was thinking about land, and that song just sort of led me in that direction.

HOLZER: It’s apt.

CAVE: Well, as I was reading the verses, there were a couple that were funny to me. There was one that read, “As I went walking I saw a sign there. And on the sign it said ‘No Trespassing.’ But on the other side it didn’t say nothing. That side was made for you and me.” It was just interesting to think about “No Trespassing,” and the other side saying nothing. To say that “was made for me” was strange, but very interesting—this sense of freedom, this sense of voyeurism, and being able to continue that sort of travel. I think it was Woody Guthrie that wrote that song. But I was thinking about land as migration, and about my family’s sort of “traveling” up from the South, settling in Missouri and Arkansas. I was thinking about that pilgrimage across the land, and land as opportunity. Then I was talking to Marie about her work, and she was looking at her Native American background and growing up in Seneca Nation and what that meant. Also thinking about the land in which the Obama Presidential Center is settling on, it was indigenous. So we were just tossing around all these ideas and then landed on the title, This Land, Shared Sky.

HOLZER: Were the lyrics referencing freedom, but aching freedom?

Exterior view of the Museum Building. Photo courtesy of The Obama Foundation.

CAVE: It was aching freedom, but at the same time it was an optimistic freedom too. Sometimes I feel that the unknown is the future. It’s the beginning of something new.

HOLZER: On a good day.

CAVE: Well, good and bad—I sort of take them all together. I’ve always had to take them all together.

HOLZER: Had you known her before? Are you established collaborators, or was this a new adventure?

CAVE: No, I did not know her before. But I was open to it. I stepped back and opened myself up for conversation. And realizing that she has to make space for me, and I have to make space for her. She’s bringing to the work these objects, what I would call these kinds of jingle cloudscapes that will hover in between the beaded landscape tapestry. It’s working with these jingles that are made from tobacco containers, rolled, and then hung by thousands in these clusters. What she calls it is, “waking up the sky.”

HOLZER: Will the airflow have them move?

CAVE: No, I think it’ll be static. But she was interested in this idea of waking up the sky and bringing the sky down to meet the earth. There’s this amazing reflective quality in the material, which she also saw as a way of making connections to one another. These jingles were used in ceremonial regalia garments to wake up the spirit, and also for healing. So I was interested in all of that, and the power within the work. With the piece that you’re doing, Freedom Riders, what drew you to that as your source of subject?

Jenny Holzer in the Studio. Photo by Virginia Shore.

HOLZER: When we first began thinking about the center—once I got over the delight and fright that came in equal measure—we were considering benches outside, so people could stay and think about the center, or think about themselves relative to it. Then I went to a place I’ve been for more than a decade now: formerly secret documents. I wondered what happened way back when and why. I find what was written in the moment to be often unguarded and thus truth-telling. Journalists do wonderful things, but people writing in the moment tell it like it is for them. I find if I read a number of formerly secret documents, then I learn something. And because not everybody spends the crazy time that I do in archives, when my wonderful group and I select things to represent to people, they might discover what they wouldn’t come across otherwise.

CAVE: Mm-hmm. And when you said getting over the fright of the ask…

HOLZER: [Laughs] Yes.

CAVE: What does that mean? What were you frightened of?

HOLZER: Not to presume, but I think a number of artists are afraid of not being good enough. I certainly am. Who wants to make crummy art? Who wants to make crummy art in a Presidential Center for a president one admires?

CAVE: I get it.

HOLZER: So that was the trembling. And I wouldn’t want to do anything but justice to the Freedom Riders who got it done at great personal sacrifice.

CAVE: Yeah, and risk.

HOLZER: Yes.

CAVE: Part of our project is being built in the studio. But the real, critical part we’ll be building right on site. So it’s going to be this sort of dance between me and Marie, really just watching the piece manifest right in front of us. So that is sort of uncomfortable, but at the same time, I know that action and that way of making, and I know how to stay open to this fluid method in the madness. I’ll set the first sort of “skin” for her to then bring her work to the surface, and then I’ll do a second layer of a second skin that will build and create volume for this relief work.

HOLZER: How many trunks and giant boxes of found materials will you arrive with?

In-process view of one of the Museum’s exhibition spaces. Photo courtesy of The Obama Foundation.

CAVE: We are arriving with four. They’re twelve-by-eight feet sort of structural panels that will be mounted to the wall. We’ll start from the bottom up, because we have to work in that direction. It’ll be these four constructive, structured panels in addition to probably fifty four-by-seven-foot beaded tarps that will become the second layer. Then it could become a third layer. They’re loosely woven so they’re malleable, and we can kind of bustle and move them around and create flow.

HOLZER: But they’ll be somewhat prefab? The tarps?

CAVE: Yeah, everything is prefabbed in the studio. So we’ll bring all that with us, and then we have about a week or two to install. Are you finished with your piece?

HOLZER: No. We’ve been at it for months, from the research to just finding the right document. I think you saw we came up with a number of finalists from a beautiful portrait of James Baldwin on a formerly secret page and more. That was many months ago. Now about thirty of us will be required to finish this thing, because I’m an idea person but largely incompetent. So thirty people who can realize stuff are on this. I think in two weeks one of the paintings will be done, and then I’m making a second one in case it turns out better. Then I will choose—or someone will choose.

CAVE: Whoa, that’s interesting.

HOLZER: So we have our own suspense built in. But you’ll be there, and if I blow it, I will be delivering something that’s… [Laughs]

CAVE: What’s the scale?

HOLZER: As far as paintings go, it’s pretty big. It’s not a giant mural, but it’s big. Human-sized large. It’s hand-leafed in palladium, so that it reflects light. I wanted people to want to walk up to it and to read it—to read the text about what they did. And the FBI stamps on it represent how the Freedom Riders were watched, and how it sometimes helped and sometimes hurt.

CAVE: Yeah.

In-progress view of the Forum Building courtyard, home to the Elie Wiesel Auditorium, the Hadiya Pendleton Atrium, and the Democracy in Action Lab. Photo courtesy of The Obama Foundation.

HOLZER: The leafing is one of the things that takes a great time, because we set it down hard but then abrade it. So there’s the mark of the hand to stand in for marks on the bodies and to represent time.

CAVE: It was interesting when I was reading about some of the arrests that were made with the Freedom Riders and what was happening in jail. They would start to break into song, which was very interesting to me in terms of a way of staying connected, and using song as this sort of healing and social power. The guards would get so irritated with them singing that they would start taking away their beds and turning down the heat, but they would still break into song. To think about what we put in place to empower and to stay connected was very beautiful. And to read about ideas of resilience, and what we do under extreme circumstances.

HOLZER: Song as armor too, as well as the gentler things you describe, are equally necessary.

CAVE: Well, I’m very excited to be in the company of you and all the other artists. This is an incredible moment in history that will be a forever moment—this is a commission that is permanent. I mean, you have permanent things all over the world, but does this one feel different?

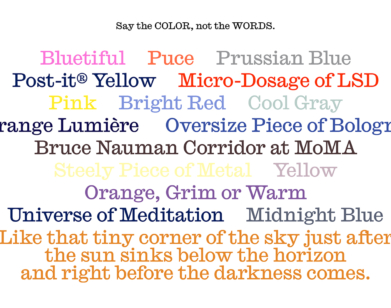

HOLZER: Information about, representation, and memorialization of the Freedom Riders should be permanent, ideally, to have younger people attempt the equivalent as needed. “As needed” is certainly necessary and urgent now. And the site is not neutral–it couldn’t be more positive. Thinking about using art for some of the goals here and goals at large, I prepared something because I was afraid I’d be too sleepy to summon it otherwise. I probably have a project in Paris next year, and the research for it included finding quotes by artists from the 19th century. I will declaim some of them, because they are pertinent, and I happen to love them. They’re from artists and their friends from literature, philosophy and journalism. See if any of these do something to you. This is from a philosopher: “The heart is insatiable because it aspires after the infinite.” That’s not so shabby. [Laughs]

CAVE: No, it’s not.

HOLZER: And this is from a smarter, more idealistic art critic than average: “Art is metamorphosed only by the strongest convictions, convictions strong enough also to transform societies.” This one seemed apt for the Presidential Center.

Exterior view of the Obama Presidential Center’s Forum Building under construction. Photo courtesy of The Obama Foundation.

CAVE: I agree.

HOLZER: And forgive me for liking this one—I couldn’t help myself—from Van Gogh: “There are so many people, especially among our comrades, who imagine that words are nothing.”

CAVE: Well, I think everything that you just read is true. I think art’s always been a reflection of where we’re at in the world, and we’ve always been the ones to illustrate that—good or bad, painful or not. I don’t even think about myself as an artist, but rather a messenger. I was chosen to deliver these deeds, and that’s it. There’s nothing more to it. And sometimes that’s hard and painful. I mean, right now it’s hard for me to deal with what’s going on, to be honest. I’ve just been thinking about ways to implement wellness, and figure out how I can take care of myself in order to do what is asked of me. What do you do for wellness?

HOLZER: Can I ask you a question so I can dodge that? [Laughs] How much of your work is born of desperation, and how much would you say is accompanied by euphoria, or relief? What are your percentages?

CAVE: I would say the percentage is 80/20.

HOLZER: Desperation’s leading the pack?

CAVE: Oh, yeah. Without a doubt.

HOLZER: Ditto. I’m a mess. But it determines us.

CAVE: What percentage?

HOLZER: High percentage. How about incalculable? There’s another dodge, but a nice word.

CAVE: I feel exactly the same. I mean, my studio has flipped on its head and can flip on its head in seconds. Everything can go awry in seconds. And that’s because it has to.

HOLZER: That sounds creative and explosive.

CAVE: Luckily, I have amazing assistants who understand the “why,” and what actions we may need to take in a particular moment. But I’m not afraid to do that, and I’m not afraid to say what needs to be said.

Interior view of the President’s Reading Room in the new Chicago Public Library Branch under construction. Photo courtesy of The Obama Foundation.

HOLZER: As long as you get it out, it can be desperate and messy.

CAVE: And messy is good, right?

HOLZER: Messy is good. But I’m just learning this, because I am a repressed hermit and I didn’t touch any art for 45 years or so. As of recently, I started doing weekend therapy where I actually make ghastly drawings and touch them. And that is, perhaps, useful.

CAVE: Yeah.

HOLZER: So far the art bites, but the process could be a sustaining force. [Laughs]

CAVE: I mean, I think that’s what we have to do. That’s what is needed in order to understand what’s next. I think about the days and sitting in front of a fire and throwing $20 bills in it. Like, “Oh my God, I’m just a hot mess right now.” But I have to work through ideas and try to find the most meaningful and most powerful message that needs to be delivered.

HOLZER: Do you have a summary statement?

CAVE: I don’t know at this moment. What about you?

HOLZER: I’m moved to repeat some of the words I found in the Obama literature, so that they can go around: courage, empathy, integrity, accountability, community, inclusivity, pragmatism, resilience, imagination, hope, elective, and then transparency.

CAVE: Marie and I are thinking not about that land, but this land as of now, and how it has to be reshaped and redefined by us as a nation. I was at that march, and I got so emotional there. It was so amazing and so intense. To be together collectively for one cause is a beautiful thing. There’s this sense of enlightenment, engagement, this collective movement that was so powerful to physically be in. To watch this collection of humanity moving across the globe all at the same time. It was just a beautiful image. That was the moment where I understood the premise of this project and the direction in which it needs to take shape, and to think about this gift that’s being given to the community at large.

HOLZER: To be sustaining and generative?

In-progress view of the Obama Presidential Center’s 21,000-square-foot ADA-accessible playground. Photo courtesy of The Obama Foundation.

CAVE: Yeah, and to enhance and to glorify the significance of arts and culture within this environment. I think about art and diplomacy, and the importance of it to be seen in this way.

HOLZER: May I watch you make your piece if I stand in the corner and don’t interfere? [Laughs] And if I don’t give you any side eye?

CAVE: [Laughs] I’m all for it. Whoever’s there will be able to have that moment to watch how two artists are collaborating and working collectively to bring together this monumental piece. So if you’re around, I may pull you in to help in some way or another.

HOLZER: I would be lucky and grateful.

CAVE: I think that’s another memorable moment that may never happen again. To be on the grounds of the Obama Presidential Center will be a very, very special time. Have you been there yet?

HOLZER: No. Probably December. I can’t wait.

CAVE: I’ve been there a couple of times, and it’s so incredible.

HOLZER: We must skulk then.

CAVE: We must. I will see you when you get there, and we’ll have tea and celebrate. How about that?

HOLZER: All right. It’s a deal.

———

The opinions expressed do not reflects the views of the Obama Presidential Center.