SMOKE BREAK

Carmen Winant on The Last Safe Abortion and the Future of Feminist Photography

Carmen Winant, photographed by Eloise King-Clemens.

FRIDAY 4:13 PM NOVEMBER 14, 2025 PARIS

In 2018, when Carmen Winant showed up to the MoMA with a shoebox of 2,000 cut-out photos, she’d hardly ever exhibited her work publicly. There were archival images of babies breaching, rivulets of vaginal fluid, taut bellies and breasts. For the museum’s exhibition of emerging photographers, her plan was to coat the walls with her photos using blue artists tape. But then she panicked. “I tried to get out of it. I said, Oh, let’s frame them.” Her curator was firm, and the blue tape would stay. And so began her breakout show, My Birth.

Since 2018, Winant’s become something of a superstar. Her style, blanketing walls in archival images, works in service of her gestalt: to reclaim and reframe images of women, especially those long erased and overlooked. At the 2024 Whitney Biennial, she showed The Last Safe Abortion, a photo installation of 2,500 prints of abortion care, featuring sterile rooms, friendly-looking receptionists answering phones, and a few flashes of Winant in mirrors. No coat-hangers or baby corpses, just the everyday tasks central to abortion care. “It’s not about me and yet it is,” Winant told me on the steps of the Palais Royal last week, where she was giving a lecture, “What Is a Feminist Picture?,” at the annual Paris Photo exhibition. After, she joined me outside to explain why her work is “fucking funky.”

———

ELOISE KING-CLEMENTS: So the lecture you just gave is called “What is a Feminist Picture?” Did you come up with that title?

CARMEN WINANT: I sort of recycled that title. That is actually the name of a class I once created and delivered where we were thinking much more about that question at face value, thinking about literal strategies and in composition, in light, in arrangement, that are feminist. I mean, I have not invented these. I want to make it clear.

KING-CLEMENTS: Yeah.

WINANT: I am feeling around historically, mostly in the 20th century, for how women and feminist photographers have approached this question. So for instance, there’s a very well-known photographer named Jeb. It’s actually an acronym for Joan E. Biren.

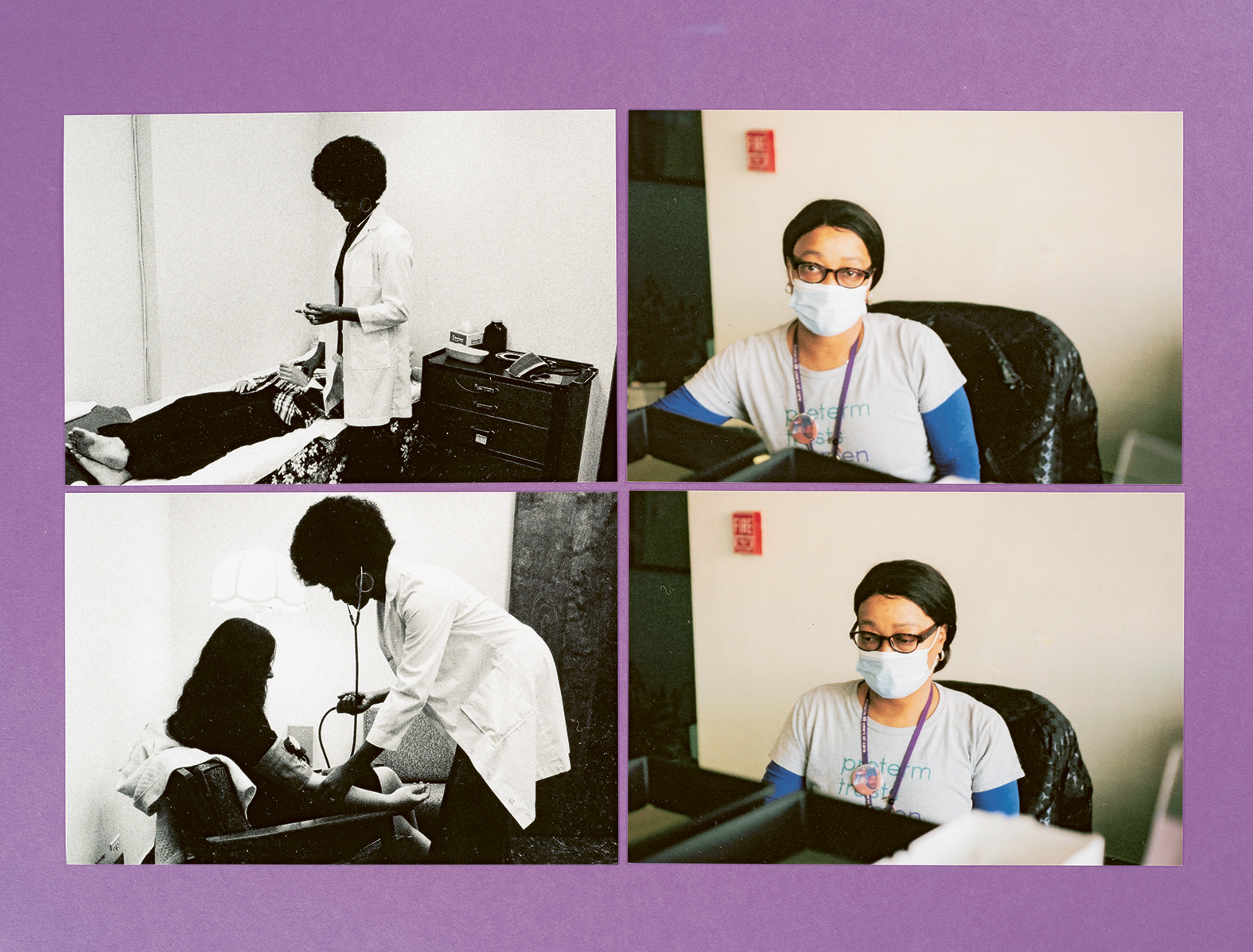

The Last Safe Abortion. Artist book, 2024. Courtesy of Carmen Winant.

KING-CLEMENTS: Okay.

WINANT: She’s still alive and is very vibrant and making pictures, but was very active in gay liberation, some lesbian separatism. She thought a lot about how many people should be in a photograph and how accustomed we are to there being a sole hero figure, not just in photography, but in art history, and how she worked to upend that by often taking photographs of groups of women. They would trade the camera back and forth, taking turns on the same mode of film or double-exposing one picture on top of another. So that’s where I borrowed the title from. And I like that it was a question, an inquiry.

KING-CLEMENTS: Online it was billed as a “performative lecture.” So I was like, “This could just be a talk, or this could be really out there.”

WINANT: I don’t know if it quite lived up to its name. I joke—and it’s not a very funny joke—that PowerPoint is my second medium.

KING-CLEMENTS: Not Google Slides?

WINANT: I like any of them. I don’t discriminate. Sometimes I make them and I don’t ever show them. Then I started to think, “Well, maybe these things that I’m making as research for myself are interesting and viable to present in relation to the work—not as an explanation of it, but as a compliment.”

The Last Safe Abortion. Artist book, 2024. Courtesy of Carmen Winant.

KING-CLEMENTS: It reminds me of your work, which you talked about as being “funky,” the way you present it.

WINANT: I feel like I’m still unlearning the inculcated sexism of the world and of art school. It’s really just the serious photographers, which is code for the white male photographers. When I was a teenager, as with a lot of teenagers, I plastered my walls with images. It was obsessive to a point that was maybe a little bit unhealthy. I would put images on top of images of images of images.

KING-CLEMENTS: What were the images?

WINANT: Oh my god, they were so corny. It was just what I had access to. I would collect Absolut vodka ads. There’d be Got Milk? ads. Then I went to art school and I learned how to be a “photographer,” in quotes, and give myself permission to start making art the way that I did when I was a teenager. So to your question about the funkiness of it, yeah, it’s fucking funky. And that was coded for me in ways I couldn’t have even named at the time as being women’s artwork and children’s artwork.

KING-CLEMENTS: Did you ever have a man in a suit be like, “This isn’t art”?

WINANT: No. If anything, I’ve been so affirmed. I’m sure people feel that way about my work, but I’ve been so affirmed by feminist curators that I’ve worked with who have lifted me up. The example I was going to give when you were asking about funkiness was at MoMA in 2018. I worked with a curator named Lucy Gallun, she brought me in having barely shown my work at that point and gave me this opportunity. But then I felt nervous about following through with the plan, which was taping birth images to the wall with blue tape, painter’s tape, and I tried to get out of it. I said, “Oh, let’s frame them.” But she wouldn’t let me.

The Last Safe Abortion. The Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, 2025. Courtesy of Carmen Winant.

KING-CLEMENTS: Wow.

WINANT: She gently talked me out of it. So I feel like if anything, I’ve had the inverse experience. There’s beautiful, refined, enormous photographs everywhere, and not only am I taping up my shitty, cut-out little images, but they are [images] of vulvas and vaginas spilling fluid. I’m not feigning modesty when I say that that was a scary and extremely vulnerable experience for me to follow through on.

KING-CLEMENTS: I do feel like 2018 was a bit of a different time. There was less nudity.

WINANT: It was definitely a different time. I can say, at least in the context of the art world, that attitude shifts have taken place between 2018 and 2025, largely around motherhood. All of a sudden, motherhood feels trendy. It’s a subject worthy of creative and intellectual inquiry.

KING-CLEMENTS: That’s great.

WINANT: But I get a little bit nervous because I’m like, “Something’s trendy.” That means at a certain point, it’s going to be untrendy. I’m so used to swinging over to a more paranoid position, so I’m trying to hold on to a more optimistic one around this.

KING-CLEMENTS: Yeah. So you put it [your images] with your blue tape, and then what? Do you go to the exhibition? Is there an opening where you’re having drinks? How do you react once it’s installed?

The Last Safe Abortion. Whitney Biennial, Whitney Museum of Art, 2024. Courtesy of Carmen Winant.

WINANT: When I’m installing it with the help of others, I’m this close to it, you know what I mean? It’s like, an inch away from my face, literally and metaphysically, so it’s hard to see. If anything, I feel like I need distance from it. Of course, I look back on older work and I think, “Oh, I would make that differently” or “I don’t like that as much anymore” or “I made these mistakes.” But they’re long-term projects, so it feels very satisfying to get them in the world to be interacted with.

KING-CLEMENTS: And there’s a mission behind that. You’re not putting a lot of ego into this.

WINANT: That’s my hope. I mean, I’m constantly trying to dissolve my ego, but I don’t know how that project is going.

KING-CLEMENTS: I don’t see any ego.

WINANT: Making art that is about service helps me to diffuse or circumnavigate the egomania of the art world.

KING-CLEMENTS: Are you taking a lot of photos now? Because I did some research and saw that you had stopped taking photos. You were mostly working with archival work, and then you started The Last Safe Abortion.

The Last Safe Abortion. Artist book, 2024. Courtesy of Carmen Winant.

WINANT: Yeah.

KING-CLEMENTS: What was that like?

WINANT: For years I didn’t make my own pictures and I really thought I never would again. There’s lifetimes of work in the archive, in the most capacious sense of that word. But then I worked on the project My Birth and The Last Safe Abortion. I made photographs in the clinics, of the clinic workers, and I also included photographs of myself in the mirror, like when I would go by a reflective surface or if I was trying to finish off a roll. I’m just so hesitant to make myself the protagonist. It’s not about me and yet it is. Quite literally, I had an abortion between the births of my children. It was terrifying for all those reasons, but I included a number of photographs that I took of myself for that reason, to really bring the project up to the present moment. Otherwise, it can be read as something just ossified in time.

The Last Safe Abortion. Whitney Biennial, Whitney Museum of Art, 2024. Courtesy of Carmen Winant.

KING-CLEMENTS: That’s a really great point. I struggled sometimes with loving photography, then also feeling really angry at photography. As a feminist, I feel like photography historically is a medium of the male gaze. To what extent do you love and to what extent does it make you angry?

WINANT: Photography is so destructive. For better or worse, I can never get away from it. And that feeling only intensifies over time. I think I feel less angry about it. I feel the potential of it in new ways. Just to give you one example, I was working on the abortion project. I traveled to a number of clinics, and I was in Wichita, Kansas, which is the site of a very infamous assassination of an abortion doctor named George Tiller in the early 2000s who was shot coming out of church. He was one of the few doctors who performed medically necessary late-term abortions in the country. They walked me around the clinic and they had this dusty $10 photo album and started flipping through it with me. It had the most historically important photographs of Dr. Tiller—the days and hours before he was assassinated, the rituals that they performed in their clinic together after he was killed. Those are very moving experiences for me that reinvent what photography can be, but also facilitate and precipitate relational experiences. I don’t see that working without the photograph between us.