IN CONVERSATION

Wikipedia’s Jimmy Wales Tells Painter Nicole Wittenberg Why He Isn’t a Billionaire

On a chilly Monday evening late last month, Jimmy Wales found himself in the downtown studio of the artist Nicole Wittenberg, strewn about with easels, paint canisters, and erotic illustrations duct-taped to whitewashed walls. You might expect the co-founder of Wikipedia to spend his time in penthouses and boardrooms, but Wales, 59, seems to have more in common with artists than moguls. Both he and Wittenberg, a longtime friend, have ambitious projects afoot: a solo exhibition, for her, now on view at Acquavella Galleries and, for him, a brand-new book, The Seven Rules of Trust, that reads as much like manifesto as memoir. “I didn’t want to write an autobiography,” Wales explained, “but I also felt like, with some of the things I have to say, the only way to explain it is to give you a story that’s meaningful.” The result is a compelling meditation on the erosion of public confidence that has led us to a moment where Wikipedia, the website Wales founded with Larry Sanger in 2001, seems like the only reliable source there is. Below, he and Wittenberg have a wide-ranging conversation about art, wealth, and the fraught state of the internet today.

———

JIMMY WALES: Well, here we are…

NICOLE WITTENBERG: Here we are.

WALES: In your studio. It’s amazing.

WITTENBERG: It’s so good to have you in America. The book is really good.

WALES: Is it?

WITTENBERG: The book is really good. I didn’t know what to expect. I just remembered, two years ago, you said you were going to write a book. I don’t think at the time I ever asked you why or what brought on the feeling.

WALES: Well, it started during lockdown and then actually I struggled with… It seems so daunting.

WITTENBERG: It’s a huge project.

WALES: It’s a huge project, but basically I met with David Drake, who runs Crown, and he said, “Have you read Peter Thiel’s book?” I’m like, “No, I haven’t, but whatever.” And he’s like, “Well, it’s not even really a book, it’s just a series of essays.” That totally unblocked me because I was really stressed out by that bigger job. But then once I started writing, actually, it turned out to be a book, not a series of essays. So that was good, but it was like I had to get through that first. “Oh my god, a whole book. How do I do that? What would it be like?” I couldn’t conceive of the whole thing upfront.

WITTENBERG: Everyone I know who does really big projects, it comes together in small pieces.

WALES: So when you’re doing a painting, do you have a full, complete vision?

WITTENBERG: No, there’s no vision.

WALES: It evolves as it happens.

WITTENBERG: I start with little things that come from observation usually, or from being in a place. I’m interested in a certain feeling I get from somebody or something or an image. I usually do a very quick sketch for 15 minutes, and I compile them all over time. Usually, it starts as a small painting, which is what’s in the studio now on the easel—a small painting that failed that I’m trying to turn around. Then over time, it builds and becomes something that is bigger than the sketch in terms of what it wants to do, but it still relies upon the feeling of the drawing. In a way, you go to a place and you have this amazing feeling or you see something beautiful. If you were to take a snapshot of it on the iPhone, it would be totally disappointing, but the feeling itself is much bigger than that little snapshot. Paintings are like that.

WALES: When I first met you, you lived in some tiny apartment and you had these enormous paintings stuck against the wall. Now your studio actually is suitable for such paintings.

WITTENBERG: [Laughs] But then you always want to make them bigger than you have space for. I don’t know why that is, but it’s a thing.

WALES: I mean, just looking at one here, I was like, “Oh, I would love that on my wall.” And then I’m like, “I don’t think I have a wall big enough for that.”

WITTENBERG: It’s not quite as big as you think. I think it’s like, eight by eight feet. But back to your book. I read it and honestly, I don’t read a ton of books like this. I don’t know how exactly I would describe what this book is, but I tend to read a lot about film and I love autobiography.

WALES: It’s not really a business book.

WITTENBERG: It gets close to the autobiography.

WALES: Yeah, a little bit. It’s got a few stories.

WITTENBERG: It has some really personal stories, actually.

WALES: It does. I didn’t want to write an autobiography, but I also felt like, with some of the things I have to say, the only way to explain it is to give you a story that’s meaningful, hopefully to you, but meaningful to me. I did read quite a lot of more academic things and so forth.

WITTENBERG: Well, it’s very substantial in terms of the academics.

WALES: It’s not an academic book. It’s a book of stories that’s more accessible in the sense that everybody’s had some experiences with trust. How do you bring that to people in a way that will make them think, “Oh, right. The world does need a bit more trust. How do we build trust in society, trust with each other?”

WITTENBERG: And then you get into the editing and into how entries are made and how they function and how it really is a non-biased explanation of facts—

WALES: Or tries to be.

WITTENBERG: Tries to be.

WALES: It feels impossible, but often it’s more possible than people realize. I think if you go on social media, even in the mainstream media, sometimes you’re just like, “Gosh, there’s no resolution to these issues.” But then it’s like, “No, actually, there probably is. We just need to take a deep breath and come at it a different way.”

WITTENBERG: That’s true. And here we are in New York City looking out over 1 Police Plaza and the courthouses behind us. It’s been a challenging time, I think, living in America, and a challenging time to live in New York. The city’s always changing, and it’s a very vibrant and beautiful city, but there has been an erosion of trust that that you described really clearly in the book from the late ’60s to the present—trust in the federal government, for example. I think of the late ’60s and I think of Vietnam.

WALES: That’s right. When people are recognizing this crisis of trust, they tend to go to what’s happened in the last 10 years: the collapse of local journalism and the rise of social media and the toxicity that goes on there.

WITTENBERG: It’s like the toxicity of anonymity, in a way.

WALES: Yeah, all of that. But then it’s like, “Oh, it’s actually been going on for longer than that.” This has happened a lot lately as I’m talking to people about the book and about social media and this and that, they fetishize the early days of the internet, like it was some magical utopia where everybody was nice and everything was Wikipedia. But I’m like, “I don’t think you really remember,” because it was super toxic. A lot of this stuff has been with us for a long time. Some of it’s just human—people are fantastic, but people can also behave quite badly if the culture and the incentives around them reward that, which is the biggest problem with social media. Bad behavior is rewarded. So, guess what? We get a lot of it.

WITTENBERG: I grew up in the Bay Area, so everyone I grew up with works at a major tech company. I remember early on there was a kind of altruistic vibe around the internet, as in, you didn’t have to listen to your stupid drunk uncle to hear about what was going on.

WALES: It was very optimistic.

WITTENBERG: It would be a free way for everyone to know what was going on, to be connected, to do things that were somehow bigger than ourselves. It had this altruistic vibe.

WALES: I think it still exists, it just gets covered up in the noise. There’s so many great places online. In the book, I talk about this group on Reddit, ChangeMyView, where they post, “Here’s my view on some topic, change my mind.” Even if they agree with the person, they’re like, “Well, here’s the best counter argument I’ve heard.” Then at the end people sometimes go, “Oh yeah, you changed my mind,” or they go, “It didn’t change my mind, but I learned a lot.” And that’s on Reddit, which is full of other great stuff, but also toxic things. So it’s all still there, and one of the things that I always reflect on is that human beings are the same as they were 200 years ago. We haven’t even had time to change.

WITTENBERG: That leads me to something that I wanted to talk to you about, because we both wrote books in the past couple years. A big part of my book, at least the beginning portion, is an interview with my friend and art historian, Jarrett Earnest. Essentially, it’s about the history of image-making and how that sits in our collective unconscious and how we refer back to it all the time and how it moves from paintings from history into paintings of present, how we are very connected as a culture to the past, and how the past and the present speak really freely to each other, even when we’re not aware of it. That’s something I’m very interested in. When I was reading your book, I was like, “Wow, that’s something Jimmy’s really interested in too.” You’re really interested in our history, our past—not in a reverent way, but in a way that it’s very much alive in the present.

WALES: Well, what is going through my mind is the history of encyclopedias, which goes back to the French encyclopedias, [Denis] Diderot and so forth. There was a moment in time when one person might have a pretty good full grasp of all the sum of human knowledge because not that much had been discovered. Now, actually, I’m a little skeptical about that.

WITTENBERG: I’m totally skeptical about that. It just sounds like a really good sales pitch or something.

WALES: Yeah. People commonly think Wikipedia is a radical break from the past.

WITTENBERG: I don’t really see it that way.

WALES: I don’t either. I’m like, “We’re actually very old-fashioned.” As an encyclopedia, we care about good quality sources, and we’re not doing original research. We’re summarizing knowledge, and that has a long history. We try to be neutral. But other than some changes, in the long tradition of encyclopedias, there is continuity with the past, and there is a certain dialogue.

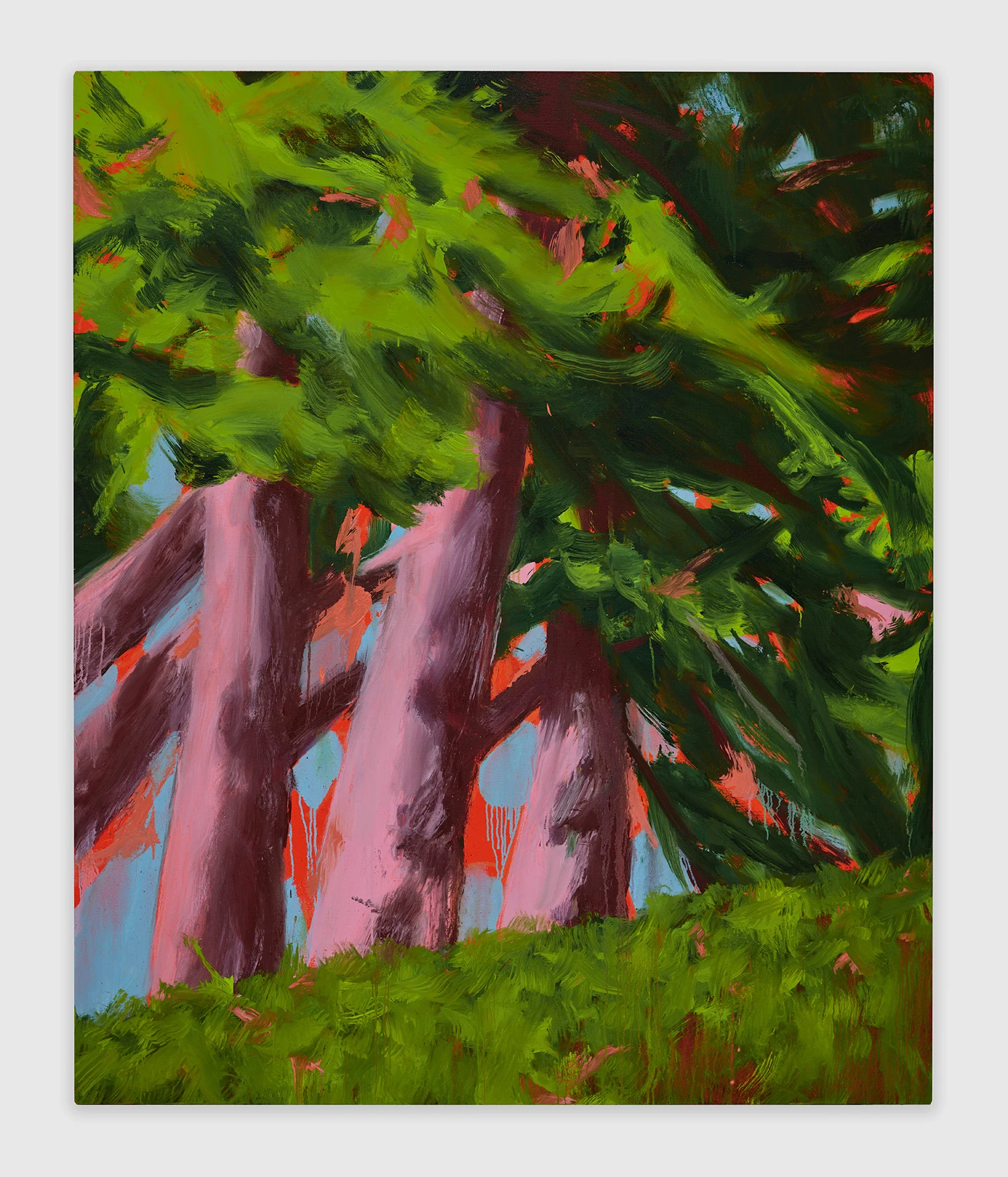

WITTENBERG: In terms of continuity, there are interesting images you bring up in the book. In my book, I was really interested in exploring how older images pop up in my paintings. Part of the book is erotica images that I was doing for a long time. Another part of the book is portraiture and interiors, and then another part of the book is landscape. These are all old ideas about subject matter, and it’s the way you do it and how you do it that makes it new.

WALES: I was going to ask you about this. I was just looking at some of the things around here. You had these quite erotic works for a while. Now you’ve moved—

WITTENBERG: I was using the internet, actually. I was looking at amateur porn.

WALES: Porn on the internet. It’s great.

WITTENBERG: But amateur porn. There’s a distinction.

WALES: Then obviously you’ve got these beautiful landscapes. Now I’m seeing some things and I’m like, “Wow, that actually is a bit of a combination of both.” I look at this and I’m like, “Immediately, that’s Nicole. There’s grass and there’s a person, but is it a naked person or is it just sensual?” Anyway, I just think that’s interesting because it’s part of your history, two eras in a bit of a mashup.

WITTENBERG: Well, we’re always becoming who we are in a way. From what I know about you, Wikipedia is something you’ve developed, but it’s not the only thing you’ve developed.

WALES: No, no, no. I am a terrible business person because I get up every day and just try to do the most interesting thing.

WITTENBERG: What is money for if it’s not to do the things that you’re interested in?

WALES: For sure.

WITTENBERG: I don’t really understand our society’s connection to material wealth. To what end? To have a certain amount of things, it doesn’t really mean anything.

WALES: I actually find it puzzling that when people are just like, “You’re a very smart person, and yet you seem to be doing…” I always think about how I live in London and the number of bankers who have far more money than I ever will, but their lives must be unbelievably boring. I don’t think they’re alleven sure of why they continue. You’ve got millions, but for what purpose? What are you going to do with it? I mean, you can get a bigger boat or whatever, but are you just keeping score in a game that you don’t want to play? Why would you want to have a high score in a game you don’t want to play? I have nothing against people making money. I’m not a communist or anything. That’s completely fine. But I hear from a lot of young entrepreneurs wanting advice and I’m always just like, “Just do the thing. Because first of all, if you try to do the thing and it doesn’t work, that’s just cool. You learn something. The next five years go by no matter what you do.” So you can just keep plugging away at the boring job that you hate, or you could just do the thing you like. By the way, you’re probably far more likely to be successful doing the thing you like than the thing that appears to make you the most money. So just do whatever’s interesting.

WITTENBERG: That is the answer and the question. Living is so precarious. Anything could happen at any time.

WALES: That’s true.

WITTENBERG: To be living your daily life with a lot of passion and enthusiasm means you’re living an interesting life.

WALES: For a lot of people, just getting by is hard enough.

WITTENBERG: Absolutely. It’s a luxury to be able to do what you want to do.

WALES: And that’s where you want to get to. Not to make billions, right?

WITTENBERG: I remember a few years ago, you had a really good idea and I don’t think it really went anywhere, but I was very enthusiastic about it. [It was] this telephone service that would take people’s payments to it and, rather than advertise the telephone service, the money would go to a charity.

WALES: Something they care about.

WITTENBERG: Was it The People’s—

WALES: The People’s Operator, yeah. It didn’t really work.

WITTENBERG: But it was the best idea. I think about it all the time. Every time I pay my phone bill, I reflect on the People’s Operator and I’m like, “God, I wish I was paying that bill right now and giving to a charity instead of putting money towards a billboard promoting my phone company.”

WALES: I had so many ideas that ultimately didn’t work, but I really care. It was fun when I did it, and if it worked, great. If it doesn’t work, there’s always another idea. For me, that’s what I value. And park of the book is, “Oh, I just got obsessed with a few ideas and I have to go and work on this because it’s fun and interesting.”

WITTENBERG: You also talk a little bit about being from Huntsville, Alabama.

WALES: The deep south.

WITTENBERG: You talk a bit about the beauty of that community, and also you refer to a specific horrific event that happened in that community.

WALES: What I think is interesting about that is that I’m talking about how humans are pro-social. People love to collaborate. They love to work together. Then I tell the story of this lynch mob who collaborated and they accomplish a goal together. The goal is horrific, and the whole event is madness. But I’m saying that this natural human tendency to want to work together with others and get things done is super important and key to our survival as a species. If you went alone in the woods and tried to live, you’re going to have a really hard time. But if you go with 50 people, yeah, you can do that.

WITTENBERG: I love being alone in the woods.

WALES: I wouldn’t survive very long, but I’d have a great couple of days. But we see this as well on social media, where people are doing amazing things. Wikipedia is fantastic, but then also you’ll see pile-ons and people just being vicious to each other and enjoying the mob scene. It’s terrible. But it’s like, “Hold on a second. Let’s stop and think about this. Humans are inherently social and love to collaborate, but let’s make sure we’re collaborating on something productive and useful.”

WITTENBERG: Another image that struck me is when you talk about communities coming together to build barns. Wikipedia aside, have you ever been to a barn building?

WALES: I have not. There’s not a lot of barn building in London.

WITTENBERG: I always had this fantasy of building a barn to paint in. I don’t know why or where this came from, since I grew up in Northern California, where there were no barns around.

WALES: I mean, you’ve got your place in Maine.

WITTENBERG: I do. I paint up in Maine. But if I had the time, I think I’d want to just build a barn.

WALES: In Wikipedia, one of the traditions that’s really old for us is giving a barn star. Apparently, this was a tradition in the older days—if someone had done something particularly good in the community, people would sneak in at night and put a brass star on the barn to say thank you. That’s a tradition that we’ve adopted. So if you do something good on Wikipedia, someone will give you a barn star.

WITTENBERG: Do you mail it to them?

WALES: No. This is just an image online. It’s really a fun little Wikipedia thing. If anybody gives you a barn star, you’ll know they’re probably a Wikipedian, because nobody else even knows this tradition anymore.

WITTENBERG: I left the Bay Area after art school. I went to art school in San Francisco, and I graduated from art school in 2001. I couldn’t wait to get out of San Francisco. Everyone I went to high school with and had grown up around, no one was really that interested in art. Then I moved to New York after spending a year in Italy looking at historical paintings and making sculpture. That was fantastic. But I realized when I got here that there were a lot of people in New York talking about this huge community of people who could buy art in the Bay Area. Everyone wanted to open the box to see, “How do we introduce art to the Bay Area?” I have my own thoughts as to why it doesn’t really work and why the people I know from my childhood aren’t really interested in art. I always thought that they were really just trying to make their own culture and they didn’t want it to resemble or to have anything to do with the more established iterations of culture, like East Coast culture, European culture, where art is more a part of our daily lives. So I was curious, why do you think art just doesn’t stick in that world, or hasn’t been able to find roots?

WALES: I think some of it is people who are making loads of money who you might think become fantastic art collectors, they’re young and they’re really busy. One of the things that I think is under-appreciated is people who are programming, they’re makers. They like making things and they like the aesthetics of the things that they’re making. It’s completely different from a painting, but it’s a thing that people are going to use and interact with and they want it to be beautiful. They get that. Programmers do have an idea about how good code is not just efficient code. It’s actually beautiful code. It’s like math. Good math is beautiful math. There is that appreciation. Painting is different from coding, for sure, but there’s an aesthetic to it that matters. Actually, I took my kids to see this fantastic [Johannes] Vermeer exhibit in Amsterdam. They brought together all the Vermeers in the world, just about all the ones they could. And what’s great about Vermeer is it’s super accessible to anyone. A kid can look at it. It’s so beautiful and it’s clearly a masterpiece. But to understand other art, it actually does help to know that dialogue and the history and the details.

WITTENBERG: But great art, for me, needs to be able to offer something to the connoisseur.

WALES: It should.

WITTENBERG: I think it just needs to be able to communicate that. No matter how much you know about art, there’s very few people who would contest your assessment of Vermeer. But I’ve spent my whole life around paintings and it’s really all I love. I wonder how the Vermeer show would’ve done in Silicon Valley.

WALES: I don’t know. But also, I think if you are into the aesthetics of coding, there’s a lot you would need to know about how this is related to something in the history of coding. So that you know the general public won’t quite get it, but you can appreciate it. So then you ought to be able to say with certain art, “I personally don’t quite get this, but I get that there’s something here that would be super interesting to dig into.”

WITTENBERG: In that way, when it comes to coding, I’m part of the general public. I don’t know about the code itself, but the application of the coding might be appealing for me. It might help me run something on my computer that I need to know how to do.

WALES: Sure. That’s very interesting. I have this whole thing about how the way children are taught coding is often so sterile that the kids are like, “This is really boring,” because they immediately start having to write little code. “Oh, great. I spent all day and my program can now add seven plus four. This is not fun.” I’m like, “No, that’s not the right way to do it. Give the kid a more advanced tool. You can actually make something.” So there is actually some great programming software for kids where you can just play with it and make a little game. I think that gives them that accessibility, and it’s more fun.

WITTENBERG: Well, it’s got to be interesting, right?

WALES: It’s got to be interesting, exactly. Actually, I have this whole thing about how history is taught and how highly variable it is from one teacher to another. Some teachers understand history’s full of amazing stories and you can really get kids super excited about amazing stories and make it come alive.

WITTENBERG: Absolutely.

WALES: In other cases you’re just like, “Really? I have to memorize all these dates?”

WITTENBERG: I still remember the name of my fourth grade history teacher because of that. Mr. Hurley.

WALES: Hello, Mr. Hurley.

WITTENBERG: [Laughs]

WALES: Oh, that’s great. So, yeah, we’re done?

WITTENBERG: Maybe. I guess so.

WALES: Yeah, but I don’t know where we stop.