Brothers of Invention: Josh and Benny Safdie

Brothers Josh and Benny Safdie make movies. They make long ones, like their Cannes-premiered features The Pleasure of Being Robbed and Daddy Longlegs, shorter ones like their “fever dream comedy” John’s Gone, and even shorter ones that play like precipitous experiments with boredom, nonsense and no-permits, with Keaton and Cassavetes-type hijinks, with strangers and spy cameras, co-conspired with neighbors, friends, and their collective, Red Bucket Films.

The Safdies’ most recent film, John’s Gone, is a coercive glimpse into the screwy and slaphappy life of guy from Queens, who, while living on the margins, reaches right into the core of what it means to be lost and in a hole. Played by Benny Safdie, John scams 99-cent stores, sells stuff online, meets with teenage junk divers and a monkey named Millhouse, answers his door only ajar, and runs—literally sprints—away from his girlfriend, Rose. But most of all, John roams. The film’s final moments portray those alien emotions, the ones we don’t see coming and cannot explain.

We met with the Safdies at their Red Bucket headquarters, and the brothers spoke at length about their film and New York city’s scrappy stamina, while restlessly balancing, nearly the entire time, on the back legs of their chairs.

DURGA CHEW-BOSE: I have so many questions! Not just about the story, but also about how you guys shot John’s Gone. What was it shot on? Film? But it looks like old grainy video, too?

BENNY SAFDIE: It’s shot on video—Video8.

JOSH SAFDIE: There was a camera that our dad got in 1988, and it’s kind of the birth of why were are filmmakers. He bought this camera and pretty much spent all the money he had on it. He was obsessed. He was a cinephile. So all of sudden he had a camera, and he was obsessed with capturing all these mundane moments, because he thought through the lens of a camera—everything became a movie.

BENNY SAFDIE: So he filmed with this camera, and it’s the most beautiful imagery you could possibly look at. It has this nostalgic feel to it, but at the same time, the colors are pale but saturated.

JOSH SAFDIE: It’s the first digital camera. It had one CCD chip in it.

BENNY SAFDIE: So we were trying to find that camera. There was this elusive pro version of the camera that our dad always wanted but could never get and we could never find that, and in the search for that, we found one that had been modified for a security camera. The lens had been cut off, because the lens couldn’t go wide enough, so they made it so that you could put on film lenses. We were able to put Bolex lenses on the camera.

JOSH SAFDIE: And to make a boring technological story short, we used 16-mm lenses on this video camera and a Steadicam at times, and we had a rig on there too… It was crazy-looking!

BENNY SAFDIE: Like a cyborg. We shot on video and then printed to film.

JOSH SAFDIE: And one thing that I kind of love to think is this idea of creating important images, creating good images—a quest. I’m on a quest for good images, always.

BENNY SAFDIE: That’s what Herzog says.

JOSH SAFDIE: Yeah, Herzog says the same thing. But I believe in that. I think that that’s important. And I think that there’s a really big obsession nowadays to have the most perfect-looking image, and every year they come up with the new camera that is the camera that everyone needs to use. I’m seeing it now in movies that are getting released and it’s the Canon 7D camera—which is fine, you know. But when everybody’s using it because they think it’s the best quality, that does not mean best. They’re using that word to describe that quality in terms of pixilation. If that was the case, if the best form of something meant the best quality, the highest resolution, the cleanest, then in painting, photorealism would be the greatest type of painting, and there would be no room for abstract expressionism. And I think manipulating an image and trying to make a unique world for your movie because you’re trying to figure out what fits it most, is what we’re interested in.

CHEW-BOSE: The look of John’s Gone really sets off John’s existing sense of turmoil. Because it’s not immediately clear what it’s shot on or why it looks like that, it makes you somewhat more concerned for him. There isn’t a lot of backstory, but that moment where he breaks down is really moving. Did you work towards that moment? Was this always a story about a guy who’s just lost him mom?

JOSH SAFDIE: That was kind of the premise to the whole character—that this guy’s mom has just died, and he doesn’t know where he’s going. There’s one line in the boxing fight, “He’s on the floor and he’s very confused, and he’s not sure what he’s supposed to be doing.” We knew we wanted to incorporate boxing in this man’s world, just the mentality of punching, and we wanted it to be a brutal quick fight. We found this fight comical but also devastating. I mean, this guy has no idea where he is, there’s this one moment where he looks right at the camera like, “What is that, what is this camera doing here?” Ronnie Bronstein, who is the director of Frownland and the lead actor of Daddy Longlegs, he’s a major part in terms of our writing process.

CHEW-BOSE: Even though it’s a short film, we care about John. Can you speak to the process of building a character in a short amount of time? What kind of choices do you have to make?

JOSH SAFDIE: Well, you don’t think about plot at all. Every movie we make, we are inspired and physically moved to write an idea, because we feel a very a specific, ineffable thing that we don’t know what it is but we’re very attracted it.

CHEW-BOSE: So what was that feeling with John’s Gone?

BENNY SAFDIE: There was actually a scene that didn’t even make it into the movie; it was like some weird cockroach thing, and I just remember having these weird dreams of stuff invading my life.

CHEW-BOSE: Wait, you or John?

BENNY SAFDIE: Me. And then I was talking to Josh, and Josh was having these weird feelings about the state of where we were emotionally. One day Josh was like, “There has to be a monkey, there has to be a monkey.” And that felt right.

JOSH SAFDIE: Well the monkey was, specifically those kids. Owen is child actor. He was in The Squid and the Whale. He’s amazing. He wrote me an email when he was fifteen, and was like “Hey I really like your work, we should hang out.” And so I started hanging out with him. It was a little strange at first. He and his friends, and teenagers nowadays…

BENNY SAFDIE: There’s no distance.

JOSH SAFDIE: They like something and they go on the Internet and become obsessed with it for 20 minutes. So I would hang out with these kids because I’d be sort of inspired by them. Their manic nature of how they absorb culture, and as a filmmaker I feel like I’m meeting these people through my craft, and especially with doing commercial work you feel like you’re selling a lot of yourself to do things.

BENNY SAFDIE: It’s just so tied into the emotional state of mind that is so fast and won’t stop. It’s indistinguishable. It’s like you’re in a blackout; you’re in this punch-drunk daze.

JOSH SAFDIE: Yeah, being punch-drunk was a major inspiration for this. Have you ever seen interviews with boxers who are severely punch drunk from their career? They’re essentially drunk from the beatings.

BENNY SAFDIE: There was also this element of not being able to connect with anybody.

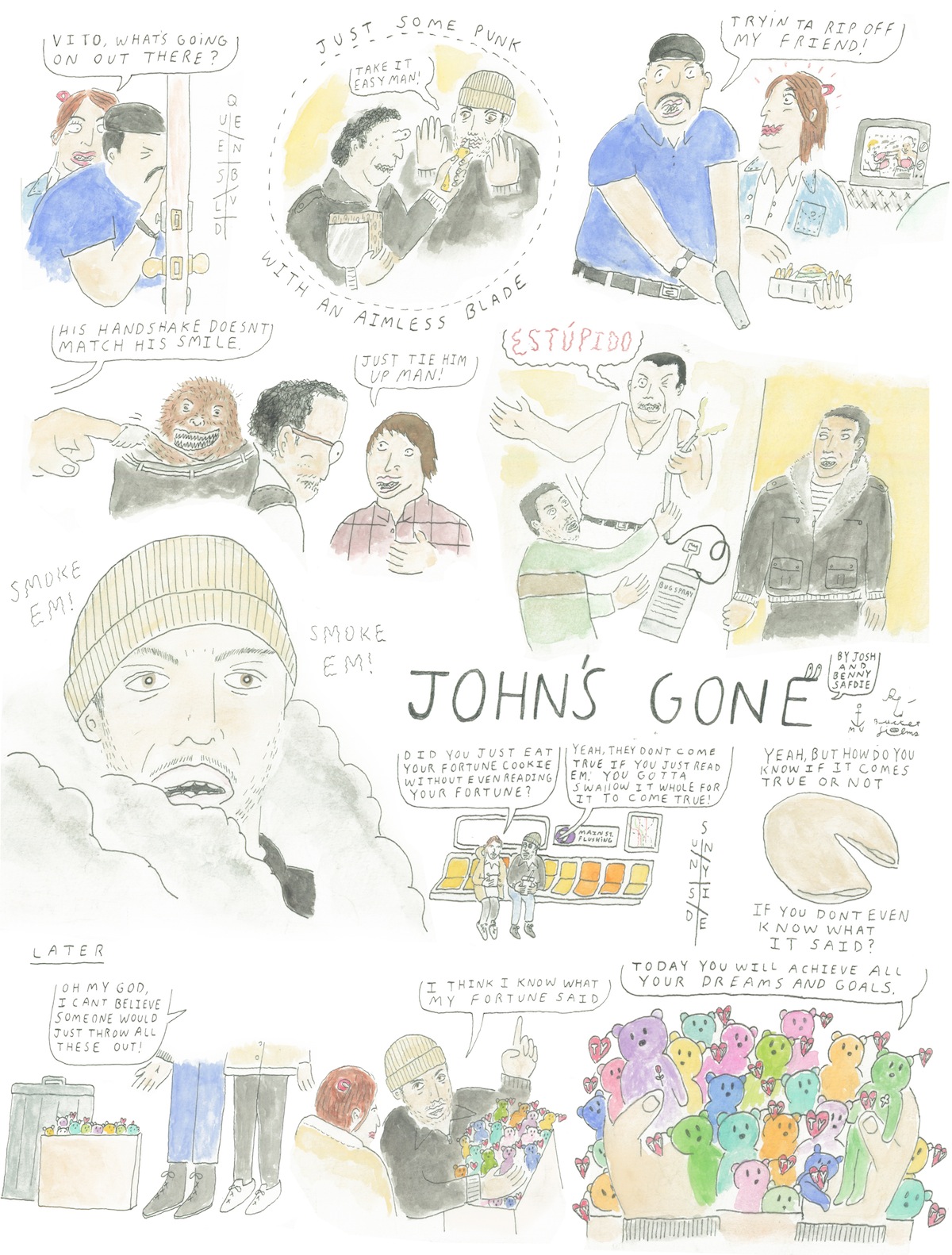

ART BY THE SAFDIES, INSPIRED BY THE FILM.

CHEW-BOSE: And what about Queens? You grew up in Queens, right?

JOSH SAFDIE: Yeah, until high school, essentially.

BENNY SAFDIE: We wanted to go back and sort of re-feel that neighborhood.

JOSH SAFDIE: When John says goodbye to Rose and runs across Queens Boulevard, and he’s hoping over the fence giddily… Queens Boulevard is the most dangerous street in the five boroughs.

BENNY SAFDIE: It’s like a six-lane highway that they happened to put a few lights on…

JOSH SAFDIE: I remember hearing stories, growing up, of full families being wiped out—like six-person families murdered on Queens Boulevard. So to be so elated to jaywalk over it, that’s suicidal, but he’s happy about it. And when people from Queens watch the movie, they always talk about that moment. And those are the type of things, for me, that really depict why I love New York. But it’s not like “I love New York” like you see in the t-shirts, it’s like what’s underneath the t-shirt, like, “I love hating things about New York.” I love yelling at myself while walking down the street. I love that when I came off the plane from Texas and I walked by a basketball court near my house, I dropped my luggage and said, “I got next.” And I just played with these 14-year-old kids and they were all concerned, like, “Who the fuck is this white guy who wants to play basketball with us?” And I was very aggressive with them, and I was so angry. I love that, that I can be aggressive here!

CHEW-BOSE: Do you think you’re trying to restore the kind of erratic energy that was once the norm in New York?

JOSH SAFDIE: This is terrible, but I think that New York is a very cyclical place. Times Square is very cyclical. People are saying it’s dead. To each his own. You know, everyone yells at me all the time because I litter a lot. The only time I’ve ever thought about littering was when I was eight years old, we were on Queens Boulevard with our dad, and we were all eating lunch from a deli. And our dad was like, “All right, hand me all of your garbage.” So we hand him tons of garbage and he shoves it in a bag, rolls down the window and just throws it out the window and onto the street. And I remember thinking as a kid, “Now that’s littering!” Throwing a piece of paper on the street, throwing your empty cigarette box, leaving a can somewhere, it’s not like I do it because I don’t care. I don’t mind seeing a lot of garbage on the street. To me, it feels more like home. I feel uncomfortable when I’m walking down some weird side street and they have like, potted—whatever you call those blue flowers.

BENNY SAFDIE: Cabbages! They plant cabbages!

JOSH SAFDIE: Yeah, that stuff is weird to me. Seeing litter isn’t. I don’t want to be a spokesperson for old New York. New York will always be New York whatever it is. And to me, I just think that it will never die because there’s a certain energy here that is very cutthroat.

JOHN’S GONE WILL PLAY AT BAMCINEMAFEST ON SUNDAY, JUNE 26. FOR MORE ON THE SCREENING, CLICK HERE. FOR MORE ABOUT THE SAFDIE BROTHERS AND JOHN’S GONE, VISIT THEIR WEBSITE.