BERLINALE

Grant Gee Made Films About Radiohead and Joy Division. Now He’s Turning to Jazz.

Over the course of his career, veteran documentary filmmaker Grant Gee has followed musicians (Radiohead, Joy Division, and more), novelists (Orhan Pamuk) and essayists (W.G. Sebald). And now, he is back with something completely new—a biopic titled Everybody Digs Bill Evans, which premiered last week at the Berlinale Film Festival. We meet the titular jazz pianist, played by Anders Danielsen Lie, during the worst moment of his life, right after the untimely death of his close friend and collaborator Scott LaFaro. The film, viewers realize, proceeds more like a thought experiment than a conventional biopic. Gee, 61, is more interested in the psychology of suffering, opening the film with a cross-cutting sequence that juxtaposes Evans’ and LaFaro’s concert with the latter’s death and its aftermath. The memory of music, emphasized by black and white colors, becomes a Proustian madeleine.

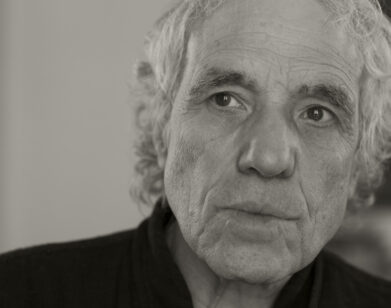

Our interview is scheduled two days after the now-infamous Berlinale press conference during which Wim Wenders argued that the cinema should “stay out of politics”—another reason why the festival has seemed to gradually decline in stature over the last couple of years. When I notice Gee from a distance in the 1,600-seat Berlinale Palast, he appears withdrawn, confirming my suspicion that Grant Gee the man might, like Grant Gee the filmmaker, prefer the shadows to the spotlight. Shortly after his film’s world premiere, he joined me to talk about his very first contact with Evans’ music and the real difference between making a documentary and a feature film.

———

JAN TRACZ: Thank you for finding time.

GRANT GEE: It’s a pleasure.

TRACZ: How is Berlin treating you so far?

GEE: I haven’t seen a great amount of it this time, but I’m back for another job for a month in a few weeks time.

TRACZ: Can you say what kind of job?

GEE: I have another strand of work, which is working with theater directors who use film and video in their stage shows, so I’m working on a show at The Schaubühne.

TRACZ: David Byrne was there two nights ago. Did you manage to talk?

GEE: No, no.

TRACZ: I ask because, first of all, I would love to see a documentary of yours about The Talking Heads. Before Bill Evans, you haven’t done a film on an American artist, right?

GEE: Is that right? Yeah, that’s true.

TRACZ: What happened?

GEE: There was no conscious changing of mind. The conscious thought was I started directing music videos that led to a couple of music documentaries. And after the second one I thought, “Okay, if I do any more of this stuff, I’m going to be typecast as the guy that does music films forever.” I didn’t want that at that time. Before this, the last music film I did was 2007, nearly 20 years ago, and I’d been trying to get another one made. And it was really almost by accident that this odd little novel about an American jazz musician was the one.

TRACZ: Do you remember listening to Bill Evans for the first time?

GEE: Yes, I absolutely do. I saw a photograph of Bill, I didn’t know who he was, and there was something about his expression in this photograph which was fascinating and made me want to listen to whatever music this person made. So I asked a friend: “Where do I start with Bill Evans?” He said, “Well, get the Sunday at the Village Vanguard album.” I got it. And I can remember putting on the first track, “Gloria’s Step,” with no expectation of what was going to come out of the speakers.

TRACZ: What did you feel?

GEE: I would have felt enchanted and charmed and excited by the deft delicacy of it. Something like that. I can’t put it into words, but I can remember the feeling.

TRACZ: What made Evans so special?

GEE: I don’t know enough about music to be able to say what made him different from other piano players. I only know it in terms of feel. I think there’s something maybe about he’s got a more rhapsodic quality than many pianists. There’s a chapter in a great jazz book called Meet Me at Jim and Andy’s, by Bill’s friend Gene Lees; it’s portraits of a number of great jazz musicians and titles the chapter on Bill “The Poet.” I don’t know how Bill’s technique is more or less poetic, but I think one can feel that there’s a poetic melancholy, even in the most sentimental of standards that he covers.

TRACZ: Tell me more about Evans’ grief.

GEE: All I know is, in the film, he didn’t talk a great deal about it. He didn’t say much about it in interviews either. What do we know about Evans’s grief? It’s odd because so little was actually written about him by people who knew him or about his emotional life. What has survived has been Chinese whispers based on one interview. So for instance, his close friend Gene Lees, who wrote the book that I referred to earlier, wrote that “He never really got over Scott [LaFaro’s] death.” That’s one person’s opinion, but it’s probably the only person who actually knew Bill, so anybody who’s written about him since has taken that quote and refracted and refracted. But if it’s true that he never really got over Scott’s death, then you work backwards to be like, “Oh, shit, what must that have been like at the time?”

We do know that after working on Kind of Blue, he decided that the modal music that he was making with Miles [Davis] wasn’t the direction he wanted to take. He wanted to lead his own trio. He’d had a trio before he worked with other musicians before. But the Scott LaFaro and Paul Motian Trio was the one where it all came together. So Bill is achieving his professional and creative dream by 1960. It reaches its apogee at the Village Vanguard in 1961. And 10 days later, Scott’s dead. That trajectory… What is that? What happens after that? He never really got over that. Let’s just imagine how that might be.

TRACZ: When I was driving here today, I was listening to Undercurrent, the album that was out a year after.

GEE: Oh, yes. I love, love, love that one.

TRACZ: And I have to say, it hits different after watching the film. He was trying to find peace after death. But was he able to find his peace, do you think?

GEE: Who knows whether he found peace or not. Undercurrent is interesting because it’s a duet with Jim Hall and I think they all could relax more when he was not Bill Evans leading the Bill Evans trio. Did he find peace? The next album that he made as leader of a trio was at the end of 1962 or maybe end of 1962, I think. You’d struggle to hear any grief in that. But whether he found peace? Yeah, I honestly don’t know. Everything I know is in the film.

TRACZ: Do you remember the cover of the album, Undercurrent?

GEE: Yeah, yeah. Yeah.

TRACZ: Because I was thinking of that photograph, this Weeki Wachee Springs.

GEE: I’ve been to Weeki Wachee Springs.

TRACZ: Yeah?

GEE: If you look at a video for the band Supergrass called “Low Sea,” it’s shot in Weeki Wachee Springs, and I shot some stuff on that and they still have mermaid shapes there, or they did 10 years ago.

TRACZ: Wow. This is your first feature, right?

GEE: First drama feature.

TRACZ: Drama feature. And is there a real difference between documenting artists and directing actors?

GEE: It’s really hard to say. It’s all filmmaking. So, fundamentally, it’s the same thing. It’s just different components of the film. Obviously in a drama, the actors are a component that you have very little of in documentaries. The biggest difference for me is, with documentaries, you’re doing so much yourself. I was joking, but other people carry things around for you when you’re doing drama, you don’t have to carry all the stuff yourself. It’s like the difference between being in an orchestra and being a solo musician. Directing actors to the extent that you need to do for a drama feature was a new experience for me. I expected that my skills in the room actually doing detailed technical direction were not going to be the best, so I tried to compensate by what I thought my strengths were, which is giving them all contextual and psychological information beforehand and talking a lot about roles. And to my mind, I did relatively little active directing. We blocked everything out, but I was asking a lot of questions. And if they had any questions for me, I would answer as best as I could. But it was about allowing the actors to propose what was going to happen here.

Everybody did so much more for this film than I imagined that they would. There was a real sense of letting people do what they do. And to a certain extent, that’s part of my nature. When I teach documentary students I’m always saying, “Just do what you do and don’t tell people what they should do. Let them do what they feel they should do, and then just a little bit of shaping, maybe.” But with people of this caliber, you just let them do what they do, and if they’ve got any questions, they’ll let you know, and then you answer those questions as best you can.

TRACZ: Can I ask you a final question?

GEE: You can ask as many questions as you’d like.

TRACZ: Death appears on so many levels in this.

GEE: Death? Yes.

TRACZ: LaFaro dies, the ex-girlfriend and the brother kill themselves, and Evans was also very young. 51, I think.

GEE: Yes.

TRACZ: What’s your personal relationship with death?

GEE: I’m getting old, so one’s aware of it getting closer. It’s weird, isn’t it? The film about Joy Division, Ian Curtis killed himself. But I don’t know about my relationship with death. What’s the Woody Allen line? “Death’s all right. It’s dying that’s the problem.”

TRACZ: That’s a great conclusion.