Trevor Paglen Dives Deep

The physical dimension of the Internet, documented through photographs, is the subject of artist Trevor Paglen’s latest solo show at Metro Pictures in New York. With it, he aims to create awareness and incite public discourse surrounding the NSA’s surveillance program, one of Paglen’s focuses even before Edward Snowden went public in 2013.

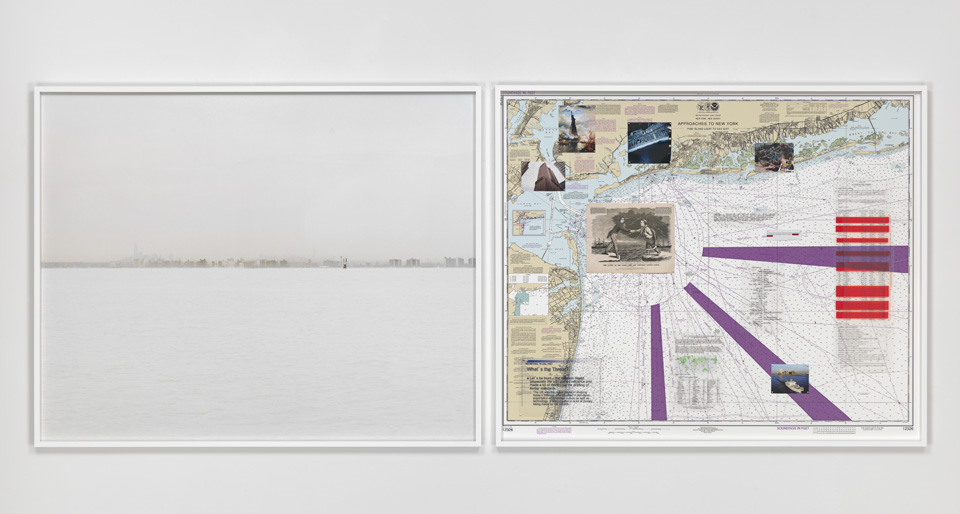

For the show, Paglen spent months researching and mapping out choke points—places where transoceanic cables transmitting Internet data merge together near coastlines—in proximity to the United States. He went on several diving expeditions to photograph these cables underwater, in effect revealing the Internet as a tangible structure that gives those in power the ability to create a surveillance state of an unprecedented scale. He photographed the shorelines, too, which are hung adjacent to corresponding maps. Paglen also installed Code Names of the Surveillance State, a video installation he’s previously staged, that depicts the code names of NSA and the U.K.’s Government Communications Headquarters’ surveillance programs scrolling down a screen like movie credits. Separately, footage shot for the Edward Snowden documentary CitizenFour plays on a loop. Additionally, the show includes Autonomy Cube, a functional Wifi source that routes traffic through Tor (a free software that enables online anonymity), making it impossible to spy on individual’s activities.

Paglen received an MFA from the Art Institute of Chicago and a PhD in Experimental Geography from UC Berkeley. He’s channeled a thirst for adventure and a resourceful, multidisciplinary approach towards research-based art projects including separate photo series of barely visible drones in-flight, secret military and government buildings, satellites in the night sky, and more.

After seeing him speak about his work at Istanbul74 in May, we caught up with him via Skype, when he was at his studio in Berlin.

RACHEL SMALL: Before you became interested in studying the NSA specifically, you were interested in surveillance and military systems in a general sense. How did your initial interest in hidden military and government systems arise?

TREVOR PAGLEN: I was doing a lot of work around prisons in the late 1990s and early 2000s, and so on one hand [my research on the] military came literally from looking at satellite photos of prisons, and old U.S. Geological Survey archives, and realizing [blank spots on the maps] were showing military places.

What started happening really quickly after 9/11 and the construction of this “War on Terror” business, is that I saw all kinds of parallels between the way that was being constructed and the way that prisons had been constructed since the early 1980s. I was interested in looking at the secrecy surrounding California prisons: for a while they had these media bans on prisons, and you couldn’t go in there. They were quite restricted in terms of the press’s access to them, and they’re also physically very isolated—I’m talking about prisons that were built since 1980 or so—they’re way out in the middle of nowhere. On the map, that physical isolation translates into a kind of invisibility as well.

SMALL: How did those prison systems develop?

PAGLEN: That’s a huge question. Basically, the short version of it is that between the late 1970s and mid-1990s the United States embarked on the largest prison construction project in the history of mankind. It got to the point where the U.S. incarcerates—in both absolute and relative numbers—were more people than anybody else in the world, including China, including Russia, including totalitarian regimes. A lot of it is related to the War on Drugs, and other mandatory minimums…all that was created. It was a conscious decision to criminalize whole classes of behaviors, and people who were not really considered criminal before that. This was constructed, both legally and physically.

Why did that happen? You could say it’s revenge for the Civil Rights Movement, which is definitely a part of the story, because what happened in the late 1960s was that politicians realized that if you said “get tough on crime,” especially if you did this in the South, that was code for, like, “put black people back in their place.” That conflation of crime with race was something that was deliberately constructed by the Republican Party in the late ’60s and early ’70s as a way to wrest control from the Democrats in the south. It’s called “Nixon’s Southern strategy.” So that’s one part of it. Another part of it has to do with the fact that the U.S. has been basically in economic decline since the 1970s and real wages have stagnated, and the idea of working class jobs that could support somebody is over. You see that economic inequality and incarceration rates track exactly right on to each other. Because when you have an economically unequal society, you end up with huge swaths of society that are disposable, basically.

SMALL: So there are parallels with how this surveillance system developed.

PAGLEN: Absolutely. There’s that, and then post-9/11, the first thing the CIA does is create these black sites: they created a network of secret prisons around the world; they create Guantanamo Bay. To me, seeing the construction of these prisons…it’s like, “Wow! This is the ‘prison boom!'” Not only in terms of the construction of them, but also ideologically, what’s going on here, in terms of demonizing races of people, putting them into extra-jurisdictional kinds of confinement, and that sort of thing.

But the other part about that, related to surveillance, is that the U.S. generally wants to solve problems with coercion. That’s kind of the default way the American state wants to try to solve problems. So there are many parallels between that: mass incarceration, mass surveillance, and militarism.

SMALL: So you were discovering these prison systems and then becoming more aware…

PAGLEN: Yeah, it shifted. I started thinking about “Wow, well I can’t think about prisons without thinking about military secrecy.” So I was looking at a lot of that—military secrecy, prisons, geography—and the links between all of these, and I think that happened when Abu Ghraib [came to light]. I think that was when I thought, “You’re on the right track.” The connections that I was seeing were real.

SMALL: This was before Edward Snowden.

PAGLEN: Well, the first thing that Snowden revealed was the court opinion showing the court order that directed Verizon to turn over all bulk domestic telephone data, using the authority of this thing called Section 215 in the Patriot Act. The government had a secret interpretation of that Section 215. One of the things that it says is that the NSA can collect data that’s relevant to a terrorist investigation. The pre-Snowden word on the street was, “Hey, there’s this secret interpretation of Section 215 that says, ‘Every phone record in the world is relevant to a terrorist investigation.'” The Snowden documents put that in writing. What the Snowden stuff did was make all of this stuff a whole lot more real for a lot more people; [it was no longer] a hushed conversation.

SMALL: Surveillance is definitely a way of keeping people in line.

PAGLEN: It has that potential. What worries me about the creation of these mass surveillance infrastructures is what we talked about before: how the U.S. typically tries to solve problems through coercion. And what mass surveillance does—even if it’s not abused right now—the infrastructure basically creates the potential where someone can literally flick a switch and form a totalitarian society that is able to survey a population more intimately than [ever before]. You have the most efficient totalitarian means of societal control that humans have ever invented. Literally just a few switches away.

So, that switch has been built. Maybe you trust Barack Obama not to throw that switch, and maybe you trust George Bush not to throw that switch, but as we look towards the future, we see inequality becoming more and more acute. We’re seeing more and more protests against cops and this kind of thing. We’re also seeing more and more natural disasters. We’re seeing more and more environmental insecurity. When you put that together as a package, and imagine those processes playing themselves out over the next five to 20 years—and let’s imagine that Barack Obama is not the President and Caligula’s the President—are you going to throw that switch? Probably that switch is going to be thrown. So I say, don’t build that switch in the first place.

This is not a theoretical worry. Because you can make a historical argument too: Show me what society that ever existed that did not use the tools that they had available. Ask any person from East Germany…you will never hear somebody say, “the Stasi never bothered me because I didn’t have anything to hide.” That’s not a thing that people say. [laughs]

Within the NSA they talk about the “golden age of surveillance,” which is now, because so many of our deepest darkest secrets are floating through the metadata that’s on clouds that we make.

SMALL: They use the words “golden age”?

PAGLEN: Yeah, they use the words “golden age of surveillance” to describe the moment now. The reach they have is so much further beyond anything that was possible before the Internet, because now, everything is digitized.

SMALL: It’s funny how the same structure that makes all these things ephemeral as well. Like, I lose my phone and all my photos are gone, but the same system makes it both ephemeral and accessible to anyone in the world. So…it’s not really ephemeral.

PAGLEN: It’s not very ephemeral! The work in the show takes that on—like where we have these metaphors like the cloud. Very mystifying things. Like, the cloud? It’s everywhere and nowhere.

For this project, there’s a lot of logistics that goes into taking these images. We’re literally looking at maritime maps and charts and trying to figure out where these cables were and trying to find places where they would emerge from the ocean floor. If they’re just on the ocean floor, they are generally going to be buried. So, we were looking for places where they would be over a reef, or something like that. I was making charts that would have GPS coordinates that would say, “Okay, if you started at this GPS coordinate and then swam to the other one, you should intersect with some of these cables and be able to see them.”

SMALL: With this work and with your other work, how would you imagine that people are able to put the brakes on the threats that mass surveillance pose? What should viewers be aware of?

PAGLEN: I don’t know. In a way, I’m not totally sure that that’s my job in the world. My job is to try to learn how to see this stuff, and connect that, and develop ways of seeing to try to see what the world looks like now. I feel like that’s really what my contribution can be. That’s a different contribution than people at the ACLU or the Electronic Frontier Foundation, who are trying to develop policy alternatives or trying to figure out how to change the course of these histories. You need all of those. The world changes because a lot of people brought a lot of different skill sets to a problem.

SMALL: I feel like people pushing for these policies get more support when they understand it more. And your show will help people understand. No one is going to be able to change anything without understanding the threat or the system. Also, I feel like, in a lot of your work, there is an underlying sense of justice. Would you agree with that or disagree with that?

PAGLEN: I guess there is. Injustice drives me crazy! [It] really upsets me when I see politicians lying…

SMALL: I would imagine that there’s a collective understanding in the U.S. that politicians are going to lie. But I feel like the people who turn a blind eye to it are telling themselves, “Oh whatever, they have to, it’s their job.” But when you look closer and you understand the deep-seated reasons why they are misleading, or lying, or launching whatever campaign, then it becomes infuriating. It’s like, “Oh no, it’s actually these incredibly awful set of things at play.”

PAGLEN: I mean, to be not outraged, or to be so jaded that you expect this of politicians is a way to have given up on the democratic project, to me, that seems very cynical… I mean, to be honest with you, I’m pretty cynical about the future, but I feel like that’s not an ethical position for me to take. It’s not okay for me to behave as if I’m cynical about the future. Even if I am.

SMALL: That makes sense. I hope this doesn’t sound like a cliché, but I think it’s important for everyone who wants to make change to balance a sort of cynical realistic side with an idealistic side, be wary while being idealistic; otherwise, there’s no way to proactively fight a disconcerting future.

PAGLEN: That’s how I feel. Even though I’ve done a lot of the social science work around this stuff—this is an important connection to make—I’m not a working social scientist. I used to be! But before that, I was an artist, and I am an artist, although, a lot of [my] practices look like social sciences, or journalism, and have methodologies inspired by those other disciplines. But we live in a world that’s so complicated you have to get all this elbow grease to learn how to see in the first place.

TREVOR PAGLEN’S WORK IS ON VIEW AT METRO PICTURES THROUGH OCTOBER 24.