POLAROID

How a Chinese Restaurant Called Davé Became the Fashion Epicenter of Paris

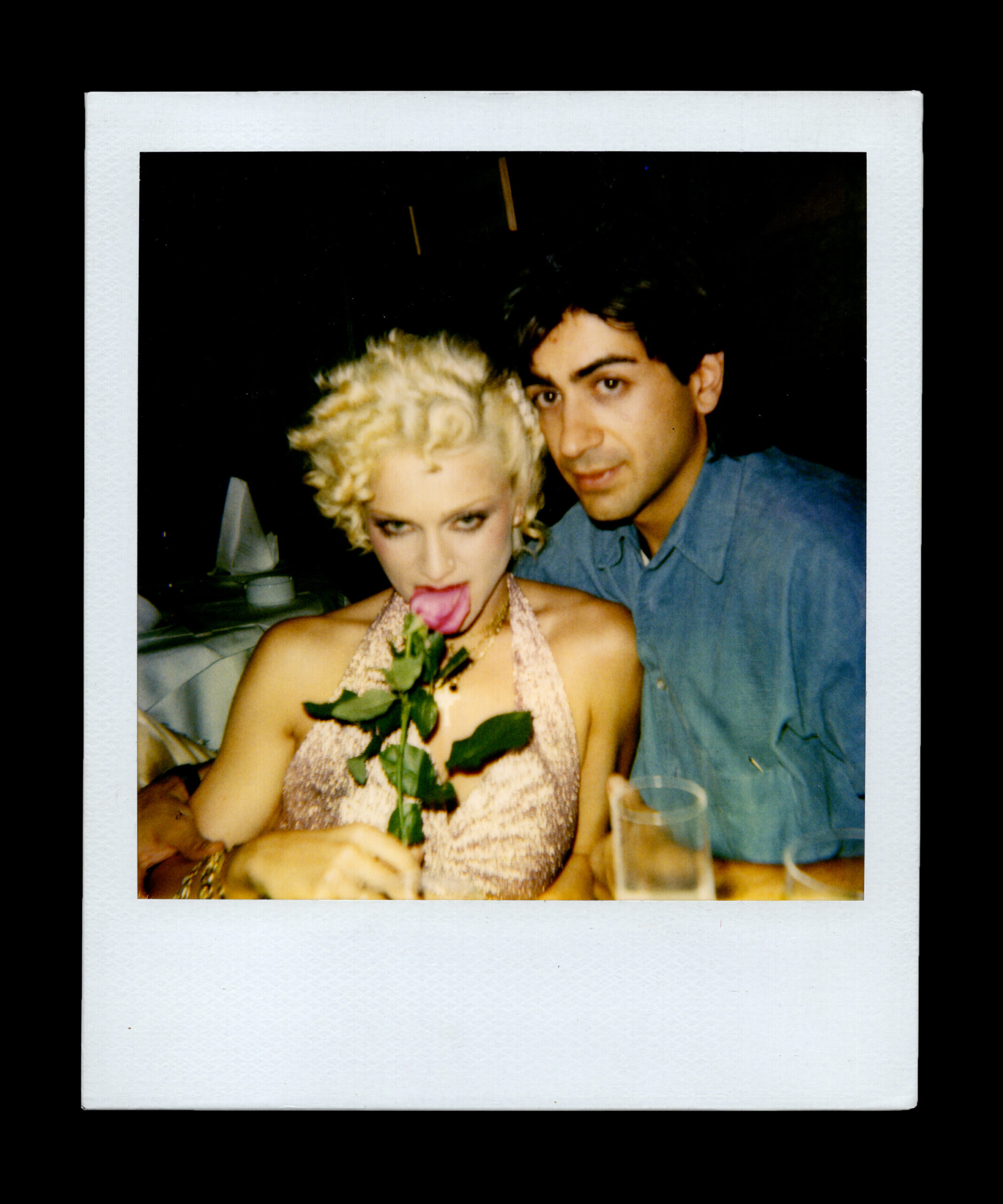

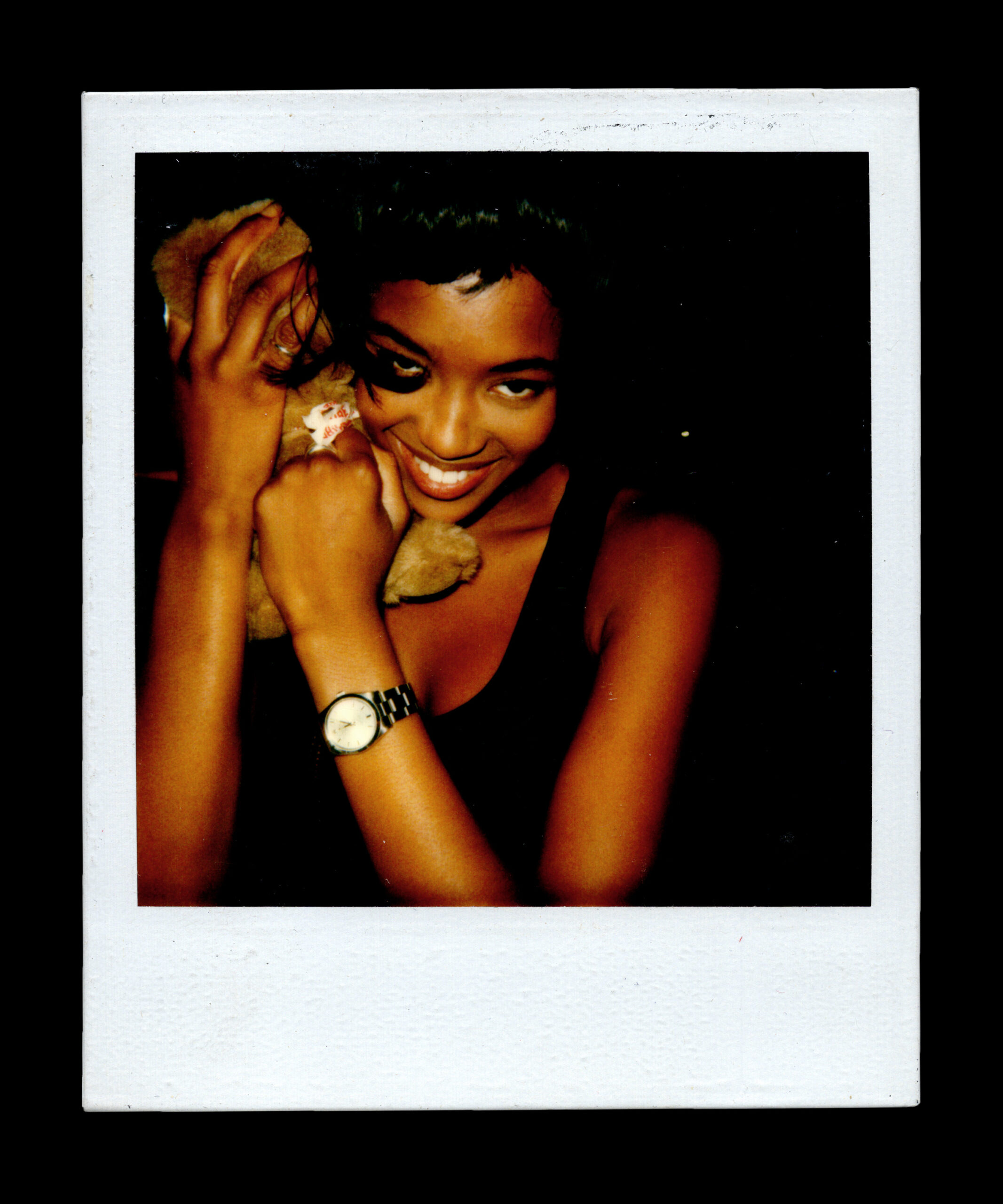

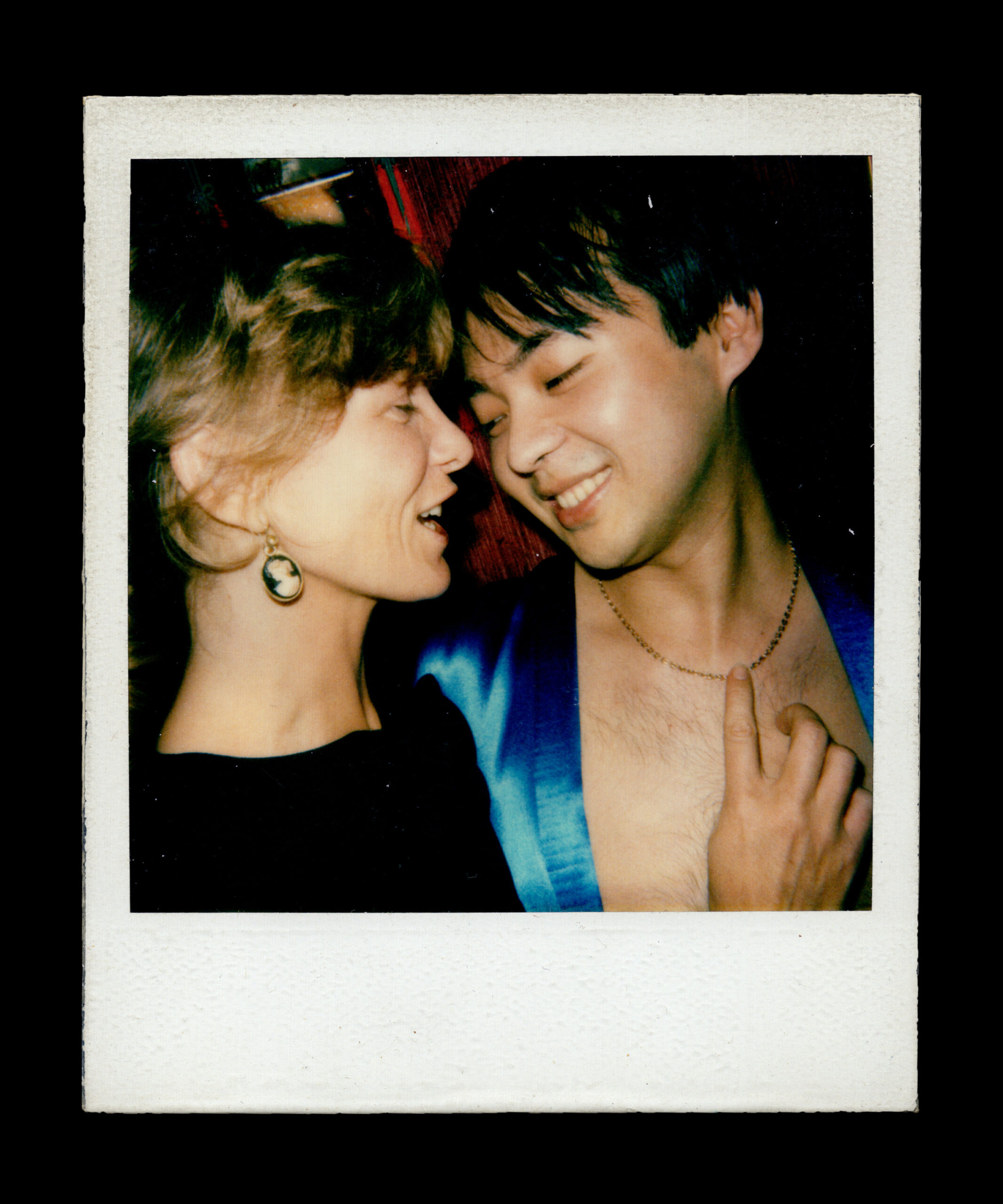

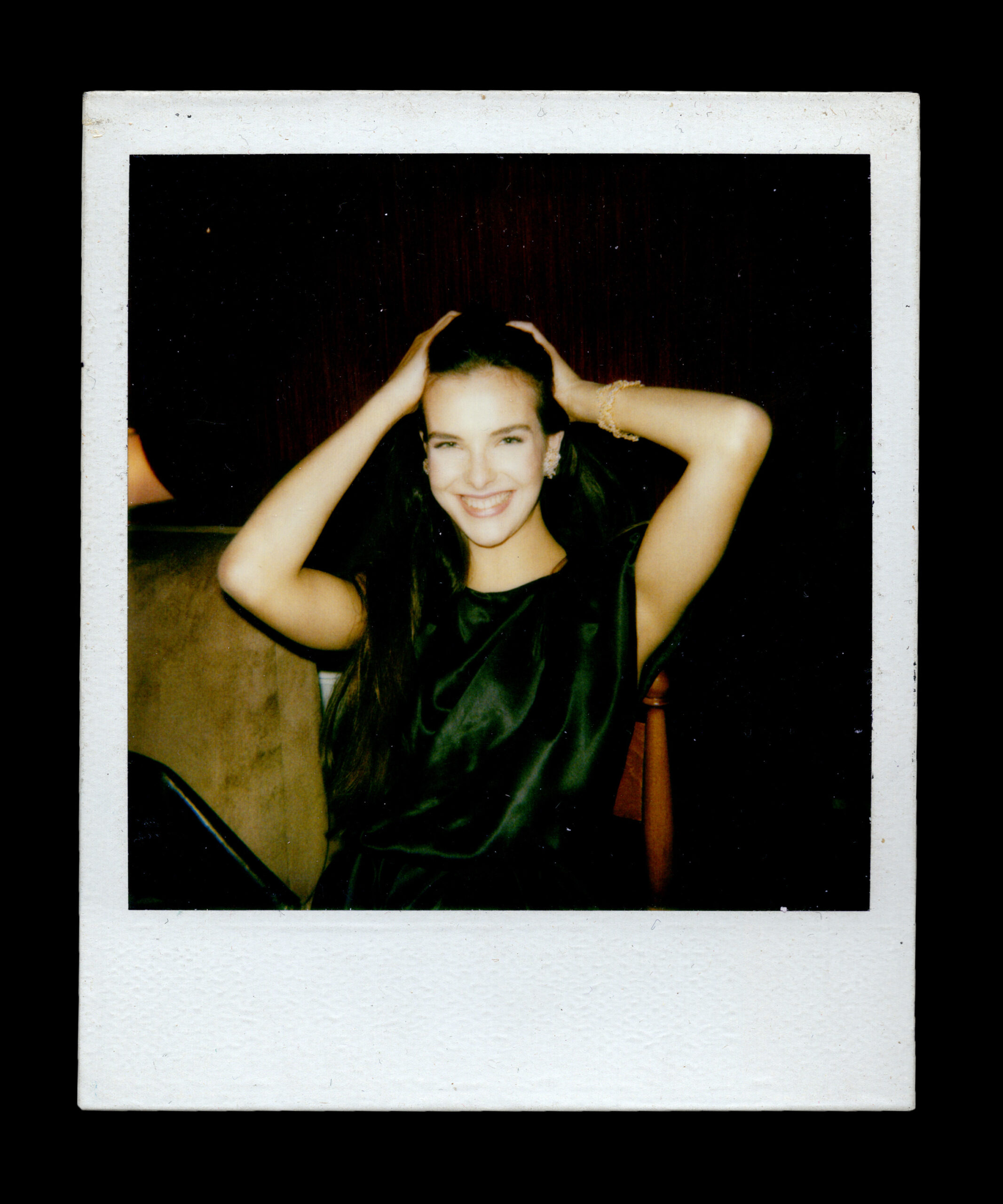

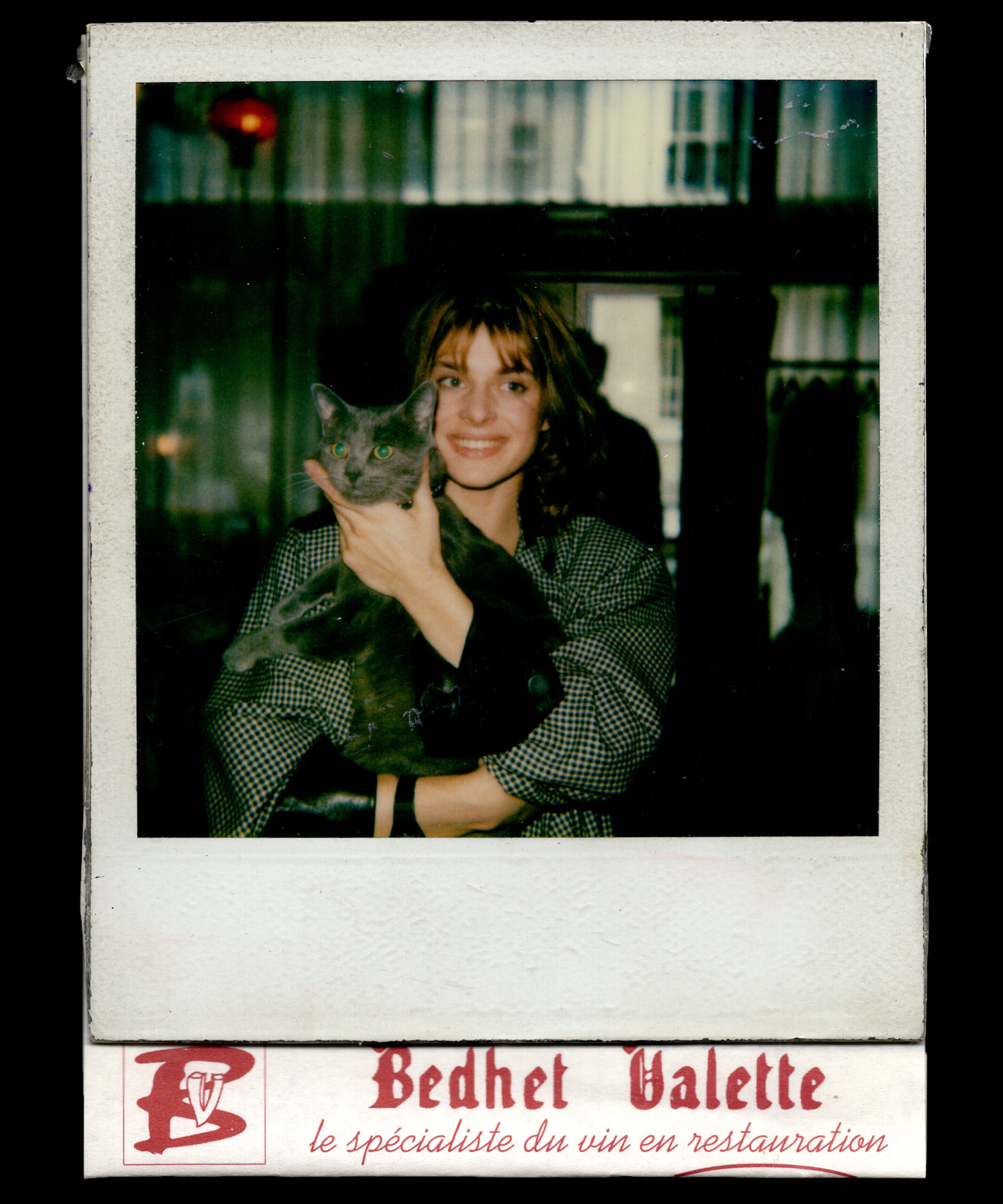

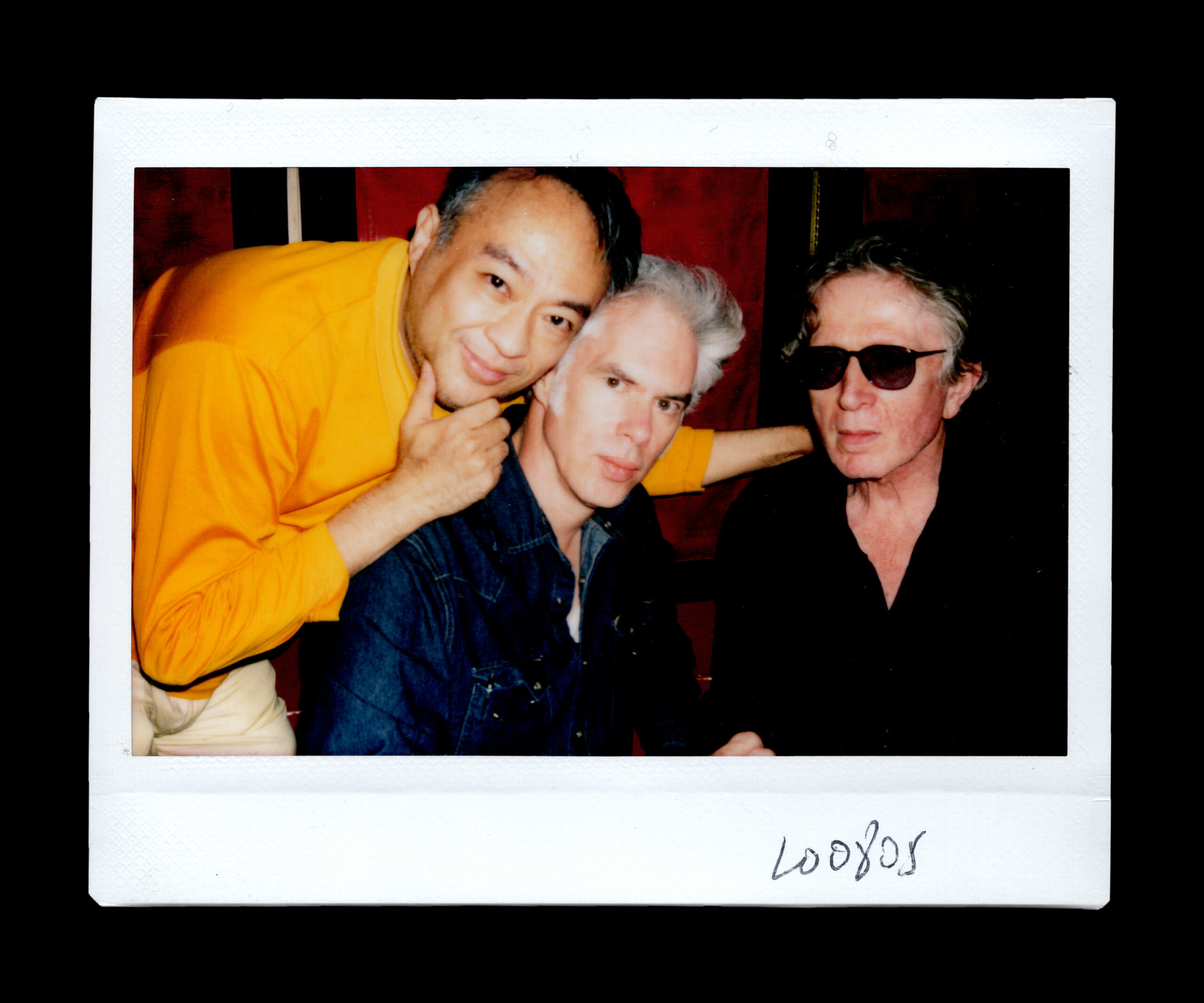

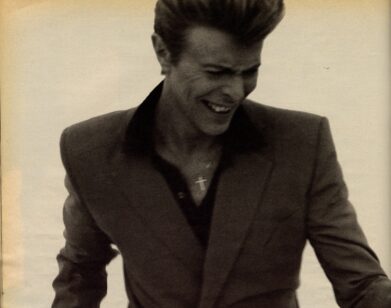

Davé with Yves Saint Laurent. All photos from A NIGHT AT DAVÉ by Charles Morin & Boris Bergmann, published by IDEA.

Davé, the legendary Chinese restaurant by the Palais Royal, was an if-you-know-you-know secret for artists, writers, and fashion elite like Madonna, Yves Saint Laurent, Allen Ginsberg and countless others in the 1980s. But it wasn’t your typical restaurant. If you knew Davé personally, you were seated without a menu, blind to prices. And what happened there stayed there. Still, Davé Cheung’s polaroids were the stuff of lore. This month, they’ve been collected by IDEA Books in A Night at Davé, a rare and glamorous glimpse into what became a mostly unsung celebrity watering hole (with a foreword by Sofia Coppola). Below is an excerpt from the book, in which Mr. Cheung himself reflects on polaroid conservation, the restaurant’s “truly loaded atmosphere,” and the celebrity regulars who he called close friends.

———

CHARLES MORIN: Can you tell me how you ended up in France?

DAVÈ CHEUNG: I was born in Hong Kong. My family came from northern China, from the city of Tianjin. They were always convinced we would go back to China. That’s why they never bought an apartment in Hong Kong—they always rented. My father even tried to live in Taiwan, at one point. But back then, Taiwan was very poor, very hard. And again, we were always thinking it wasn’t permanent. We heard rumors they’d invade China with help from the Americans. And you choose to believe it. Because believing you’ll go back is less painful than telling yourself it’s over. But when the Cultural Revolution arrived, we understood. It was finished. No turning back. Purging.

MORIN: Have you never returned to China since?

CHEUNG: Only once. In 1989, when my father died. My mother and I went back to the place where he was born. We stayed with my aunt. One day a man showed up. Dressed very simply, almost plain. Very polite, yet very strict. He asked us how long we intended to stay. He already knew the answers. Then he asked for our French passports. He said, “We’ll return them when you leave.” It was both strange and chilling. But back to why we chose France… When my father arrived in Hong Kong, he had some money—that is, gold and US dollars. My mother had a childhood friend who had helped her a lot upon arrival in Hong Kong. That friend worked for the French consul. When he was appointed ambassador to Afghanistan, she went with him. After Afghanistan, the consul returned to Paris. There, my mother’s friend met other Chinese people, she opened a restaurant. Then she returned to Hong Kong for her father’s birthday and, of course, came to see us. She told us about Paris. Easy work. The “Trente Glorieuses.” A time when the word “unemployment” didn’t exist. It made you dream. In Hong Kong, things were getting harder, so we went to the consulate. There, someone drew up a document promising to get us jobs in Paris. My father left first, six months before us. My mother had to sell all her jewelry. Back then, a plane ticket was very expensive. No charters, none of that. I remember people dressed up for the flight. The women especially: in suits, heels, very chic, from big fashion houses. It was a real departure—almost a ceremony. I was about to turn fourteen.

MORIN: How did you start taking Polaroids?

CHEUNG: I bought my first Polaroid camera on June 1st, 1982—surely influenced by Andy Warhol’s Polaroids—and I found the images extraordinary. The colours were more beautiful than reality, better than any photo. I don’t quite know why, but there’s something about the instant moment that elevates everything. Jean‑Baptiste Mondino taught me to focus properly and, above all, to capture my subject well, to center it.

MORIN: And it all started on Rue Saint‑Roch, in your first restaurant, right? Not on Rue Gambey, in the family restaurant?

CHEUNG: Yes, it started on Rue Saint‑Roch. That was my very first restaurant. Rue Gambey was a small place, but in the end already a scene. I wasn’t taking Polaroids back then. I watched, I observed, but I didn’t photograph. It came later—like a reflex. When I needed to keep a trace, hold on to an emotion.

MORIN: Your Polaroids are in exceptional condition. But I remember that in your restaurants, whether Rue Saint‑Roch or Rue de Richelieu, most were on the wall, under glass or sometimes just pinned—so utterly unprotected, not from light or smoke. And I remind you, your restaurant allowed smoking even when it had been banned. Can you tell us how you managed to preserve them?

CHEUNG: Polaroids are extremely fragile. As I was clever, those I displayed on the wall were copies. The originals I always kept safe—in boxes, filed in my archives. They remained intact, almost. Like memories one would protect without saying it.

MORIN: What did you photograph first? Did you photograph someone? Or was it the place, the restaurant?

CHEUNG: The first pictures were actually of my sister. Experiments. Tests to understand how light reacted and played. Nothing premeditated, just the urge to see.

MORIN: And the first time you photographed a famous person, how did you ask them?

CHEUNG: People love being photographed. And with Polaroids you see right away how the image looks. You feel like you have real visual control over yourself, which is reassuring.

MORIN: Have you ever had people ask you to tear up a Polaroid?

CHEUNG: It happened. We laughed, people laughed. And then they wanted to take more. I remember especially a very beautiful Italian actress. We took a few photos, she didn’t say anything at the time. But as soon as she left, she sent someone to take the photos from me immediately. She was wrong… and right. Her face was so strong. There was something. Often those who say they don’t like being photographed have a very precise self-image. Like Marlene Dietrich. They want the photo to exactly match what they see in their head. People always see themselves from the same angle. But with me, there was trust. It was like an implied agreement.

MORIN: Do you remember people who were difficult about their image?

CHEUNG: I remember someone from the 80s with whom you had to be extremely, extremely cautious. I’m talking about Valérie Kaprisky. She wasn’t perfect, but that is exactly where beauty lies. One of the friend of filmmaker Andrzej Żuławski once told me: “She has a gift, like Bardot. She doesn’t realize it.” And it’s true. As soon as she moved, in movement, in abandon, even without clothes—there was such grace that it was never vulgar. That’s the gift of a born gymnast: every millimeter counts. As if she were always balancing on an invisible beam. So she refused to be photographed with others. I was able to do one portrait of her… but frankly, it’s completely silly. Nothing interesting. Then everyone got the Adjani syndrome.

MORIN: It’s true that you have no photo of Isabelle Adjani among all your Polaroids?

CHEUNG: She made everything so complicated… You saw perfectly at Cannes, you know, when photographers laid their cameras on the ground to protest against her, against her attitude. Then I think she understood it was over. She annoyed everyone. It’s also the story of Maria Schneider. I knew her very well. After Last Tango in Paris, everything derailed for her. The truth is, she was so timid she became impossible to manage. She claimed her place by opposing everything. That was her language. She became perfectionist. It wasn’t caprice. It was a way to show she had control. A way of saying: I am precise, I decide. A way to survive, no doubt.

MORIN: Yet she had absolutely no control…

CHEUNG: You’re allowed to piss everyone off as long as you bring in money. If you bring in money, they turn a blind eye. But once you cost an arm in tantrums and you no longer bring in anything at the box office, it’s over. She had done a film with Carole Bouquet—Bunker Palace Hotel. Maria told me Carole was very kind with her.

MORIN: You were close to many actresses, but Aurore Clément is your best friend. If I understand correctly, you call each other every day. Besides, she’s the wife of Dean Tavoularis, the production designer of Francis Ford Coppola, who are also two of your friends.

CHEUNG: With Aurore, it’s a bond that doesn’t break, a fraternal love. What few people know is she was supposed to play the role of Maria in Last Tango in Paris. She and Maria Schneider were the two finalists. But during the casting, Bertolucci asked her to take off her blouse. She messed up with the buttons somehow. I think that’s what changed everything. We see her nude in Lacombe Lucien, a film of unsettling ambiguity, and also topless in Apocalypse Now. So nudity wasn’t a problem for her. But maybe it was different there. In Apocalypse Now, she told me she had to film the love scene with Martin Sheen under the eyes of Martin Sheen’s wife, who was literally next to them, very jealous. Carole Bouquet told me the same on the set of James Bond, with Roger Moore. His wife was constantly present, surveilling. Afraid he’d run off with the young Frenchwoman. After that casting, Aurore said to Maria on the way out: “I’m sure the role is yours.” And later, Bertolucci confessed to his biographer that the film would’ve been completely different with Aurore. In Lacombe Lucien, she is heart‑wrenching. She brings an incredible softness. A light in the midst of brutality.

MORIN: How did your first meeting with producer Jean‑Pierre Rassam go?

CHEUNG: Very funny, very seductive. The first time, he came to dinner with Francis Ford Coppola, Dean Tavoularis, Carole Bouquet, and with his cook and his own food. He loved to provoke, to see people’s reactions. So I told him: “At least, let us reheat that properly!” He saw I didn’t mind, that I played along. After dinner, he suggested we all go for a drink at Les Innocents, a trendy spot just next door. To me he said: “You come if you want!” He ordered champagne as only he knew how. And I, who don’t drink, went to pay the bill. It floored him. He was truly impressed. Because nobody did that—on the contrary, everyone let him pay. After that, a true friendship was born. He came every day. To the point where Carole Bouquet once asked me: “But what did you do to my husband?”

MORIN: Have you ever been tempted by excess? Drugs?

CHEUNG: Back then, those circles were still porous. The rich and poor mixed, socialized. Only the truly, truly rich formed a separate caste. So drugs circulated in a way, let’s say, less transactional than today. When I was very young, I found myself at a party. Sitting on a huge sofa—enough for twelve people—to talk, laugh, party. Around me, two people had big shiny eyes, a bit too happy. A plate was passed around. I didn’t know what it was. People sniffed, and someone offered it to me. I said, “No thanks.” I didn’t have to repeat. The two young people jumped on it. But I was perfectly fine. No need for more. Another time, it was at an even stranger party. A deputy, very close to Jacques Chirac, had stolen from his slush fund to organize an opium soirée. But attention—the idea was not to smoke it nor ingest it. A girlfriend of ours had had a “brilliant” idea: she emptied ultra‑yeast capsules with a hat pin—they were common then—and turned them into suppositories. She even prepared a ten‑hour pre‑recorded soundtrack so the party would last, the effect build up slowly. And me, as usual, I took nothing. Yet I was in complete sync with everybody.

MORIN: You never needed anything to get high?

CHEUNG: No. When there’s a real drug in the air, a truly loaded atmosphere, I feel the same effects without taking anything. There’s a scientific word for it—I should have noted it, I forgot. It’s like a form of mental assimilation. It passes through the mind. A kind of human photosynthesis, perhaps? Jean‑Pierre Rassam used to joke: “You’re lucky—at least it’s cheaper!”

MORIN: Can you talk about Marguerite Duras? She came to your place often? She didn’t travel much, right?

CHEUNG: She had her routes, her habits, her fixed places. And she came to mine often. Never alone—most of the time with Bulle Ogier. She really had a uniform: turtleneck, vest, ankle boots, glasses… Always the same silhouette, the same clothes, the same glasses. Frédéric Mitterrand once told me a very funny story. One day he was at her place and someone rang the doorbell for New Year’s gifts. Before opening, Duras hid her face under a hat—without her glasses, without her uniform. He asked: “But why are you dressed like that?” She answered: “Imagine if they recognized me!” She knew exactly what she represented. She had built that image. She cared about it. She had a massive ego. But without that ego, she couldn’t have written some of her books. Gorgeous books. Of extreme violence.

MORIN: And who were the first personalities to come to the restaurant?

CHEUNG: Brion Gysin. He brought photographer Bettina Rheims and writer Serge Bramly. At that time, she was pregnant with their son. She found the place charming, so she wanted to organize a dinner for one of her friends at her apartment on Rue de Turenne. We took care of the dinner. But before that, I’d already crossed paths with Éric de Rothschild at one of those slightly shady soirée, and Bettina realized I knew her cousin. There was also Loulou de la Falaise, and part of the Saint Laurent crowd. I got a bit flirted with by some very kind gay men and I let them escort me back to the restaurant. It was charming.

MORIN: It was a bit like your debutante ball, right?

CHEUNG: Exactly that. Since Loulou adored it, she wanted to organize something similar at her place on Rue des Plantes, in the 14th, with her husband. They asked us to provide the dinner. Thadée Klossowski, her husband, came to pick it up at the restaurant. But since it wasn’t ready yet… well. This guy, how to say… he’s a funny bird. A sweet madman. He spends his days bored, hanging at the café, playing pinball. And at night, he transforms: tuxedo shirt, sleeves rolled up, a little decadent air. So he arrives and whispers to me: “I can’t wait, I’m in a hurry.” He asked me to put everything in a taxi. But since there was an upstairs to climb, I had to go up myself. It wasn’t as simple as he imagined. Loulou was the queen of Paris. So obviously everybody was there. Everyone was pulling strings to be invited. That night, I met the whole world.

MORIN: At that time, did you know who all those people were? Were you aware of their significance?

CHEUNG: No. What I saw was they were all well-dressed. But I soon understood that behind it, there wasn’t much. Everything was in the outfit. Take some people—if you take off their undone cufflinks and their cigarette, there’s nothing left. Not even an attitude. Just a pose. You know, an attitude is a sequence. A way of being. Here, there wasn’t even movement. They’re incapable of continuation. There’s no follow‑through.

MORIN: You always preferred to be surrounded by writers and artists?

CHEUNG: Yes, it’s true. People like Martin Kippenberger, Jean‑Jacques Schuhl and Ingrid Caven or Helmut and June Newton, Aurore Clément, Carole Bouquet, Jean-Pierre Rassam, Jacqueline Finnaert, Javier Arroyuelo, Eduardo Arroyo and Grazia Eminente. But not only that. Experts in art or antiquities. Colorful people—but with substance. What I loved was getting an education.