DANCE

How the Choreographer Jacob Jonas Turned Pain into Movement

Photos courtesy of the Jacob Jonas Company.

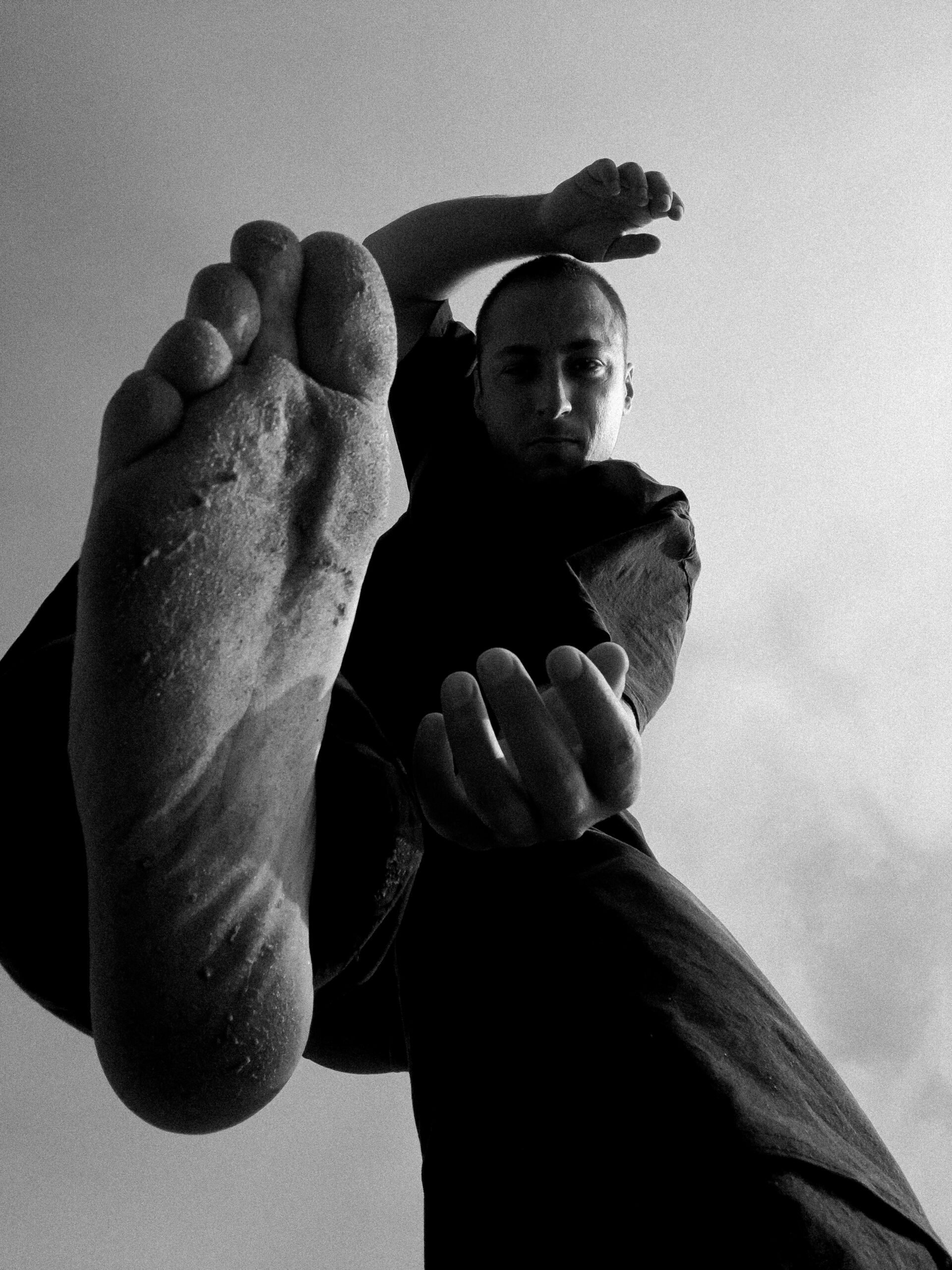

When I first met Jacob Jonas nearly a decade ago, he was already fast becoming one of contemporary dance’s most distinctive choreographers. No conservatory pedigree, no institutional blessing—just a kid from Santa Monica who learned to dance alongside street performers on the Venice boardwalk and chased light with a camera. By 30, his company had a residency at The Wallis in Beverly Hills; he’d choreographed tours for Rosalía and Kanye West; and collaborated with Britney Spears, Elton John and SIA. His explosive style, shaped by childhood trauma and chronic illness, eventually reached the fashion world through partnerships with brands like GAP, Longchamp, and Kappa.

In November 2022, Jonas was diagnosed with stage 4 lymphoma, a rare side effect of his Crohn’s medication. Rather than retreat, he documented the experience through journal entries dictated to his partner, Jill Wilson, and unabashedly raw selfies as he both unraveled and rebuilt his relationship to his body. These reflections became the basis for Cemented Beauty, a book co-published with Atelier Éditions. Ahead of its release this fall, Jonas and I caught up to revisit those entries—the frustration, the enlightenment, the recalibration—and discuss how survival informs his work now.

———

KYRA BRESLIN: Thank you for being here, I’m so excited to talk to you. As you know, I think that you are an incredibly gifted storyteller, from dance to photography to film, and one of the lines in the book that I love is when you say that you can see the dance before it happens, or the photo before you take it. So what’s the story that you’re trying to tell right now?

JONAS: I’ve been practicing closing my eyes recently, taking a lot of deep breaths, and just seeing what ideas come to me. Over the past two years, a lot has come up during the time of healing about my life and childhood. I guess dance and creative expression has always been a way to organize and find therapy in what I’ve been going through. So it’s just about continuing to find ways to express myself while navigating what’s going on in real time.

BRESLIN: The title of your book is Cemented Beauty, and I feel like that holds a lot of meaning. How did you land on that name?

JONAS: While I was battling cancer and going through chemotherapy, people kept asking me, “What’s going on?” or “How does it feel?” And all I could really think about was concrete, that everything around me felt very heavy and cemented. But the journey itself was really beautiful in some ways. So the title just kind of occurred.

BRESLIN: I think it works perfectly. When you received your cancer diagnosis, you were at the height of your career. The odds were uncanny, yet it happened to you. It was a super, super rare side effect of a drug that you had taken for 10 years for your Crohn’s. What was that shift like?

JONAS: Yeah. I’ve had Crohn’s for a large part of my life. I was hospitalized when I was 21 for a few days, and life kind of stopped there. Everything was put on hold. So when this whole journey started, it felt very similar, except the duration was much longer. But yeah, there’s nothing like being in a hospital room and being in a hospital bed. The treatments I was on didn’t allow me to leave my room, just from the chemicals of the chemotherapy and the drip. When this first started happening, a close friend of mine said I could approach this with fear and anger, or with gratitude for the opportunity. I really just tried to find gratitude in the stillness, and it became very peaceful to surrender.

BRESLIN: Having been so busy performing, constantly working with fashion brands and musical artists, did you feel like you were missing a part of yourself in a way?

JONAS: There was a moment after my second treatment where the chemotherapy created this perforation in my stomach, and my life shifted very quickly. I was in a lot of pain and on pain medications that caused me to have these hallucinations. I remember there was this one moment at like four in the morning, I went on my phone and started looking at my Instagram feed. It’s interesting to think about the reality that we’re all in. When you’re in those circumstances, you see how delicate life really is. The brands, the fame, the artists, and the popularity of life becomes really insignificant. I just kept visualizing myself being at the beach. That’s what became very important to me, being around nature.

BRESLIN: That makes sense. One of my favorite lines that you wrote was, “I need to find myself as the dancer again, not the director.” I just thought that was so profound, this idea of relinquishing control to the doctors, to your illness, to your own body. What did that surrender feel like?

JONAS: Yeah, a lot for me came up about control. I think a lot of us tend to be in control. And in some of those moments, there were just things that I couldn’t comprehend, and I really had to just allow the doctors to do what they wanted to do. So that’s kind of what it became, the idea that I needed to trust the process and allow what wants to become, to become.

BRESLIN: Another thing you talk about is having spent so much time alone in this forced stillness. You describe it as both a betrayal and a gift, and that it gave you an opportunity to unlock your mind in a new way. Can you talk to me a little bit about that?

JONAS: When I was in the hospital and during the whole process, I would often look up to the sky. Because I live in Santa Monica, I always notice birds flying. They’re either flying towards the ocean or away from the ocean. Sometimes when I get really busy, I don’t do that. I don’t look up to see the birds or notice the clouds or the things around me. I think stillness and meditation allow a lot to come in through the vessel and provide guidance, healing, and messages. When we’re so distracted by what’s going on in the outside world, we miss those messages. I think I was really fortunate to be in a position where so much stillness occurred, and a lot more messages came in.

BRESLIN: So you were having these moments of clarity and epiphanies. A lot of the journal entries felt like I was seeing these epiphanies. Do you still feel that way, or not as much?

JONAS: I don’t know. Reading the book now, two years later, I kind of feel envious of that version of myself that was there. After I finished chemo, I went through six months of PTSD—or at least that’s what certain people called it—where I had visitors in my mind, and I wasn’t very familiar with them. I’m relearning how to build that relationship. I think my relationship to mushroom therapy, or psilocybin therapy, have helped me recapture some of those insights I had then. But the version of ourselves inside is always changing, and trying to document where we are at certain times allows us to hold on to some of those learnings in real time.

BRESLIN: It’s also really interesting that we’re having this conversation right now, as one of your past collaborators, Kanye West, is in the headlines again for his new documentary. You’ve worked with him on and off since 2019, and there were several controversies during that time. But in the book, you thought about him a lot and even reconnected with him after your treatment. Can you tell me about that experience?

JONAS: Yeah. When I was first hospitalized in 2022, he had gone on his first anti-Semitic rant. I had a lot of frustration with what he was communicating and felt that the universe was going to reconnect us at some point and I was going to be able to tell him about my frustrations. After I had finished chemo, we reconnected through a mutual friend at a birthday party. I talked to him for a couple hours that night, and I was like, “I don’t know what you’re doing.” You admire giants like Steve Jobs and Walt Disney, but they used their gifts to produce creativity, and you’re using your voice to elicit pain and hate in others.” That conversation sparked a newer friendship with him. We took many walks on the beach, rebuilding our friendship and working relationship. It was helpful for me at that time. He supported me when he knew I was sick, and I think I helped him in some ways, thinking about the gifts I was receiving through my healing chapter and sharing those with him. I went through some serious mental health issues after finishing chemo, and that helped me empathize with him in ways I hadn’t before. Ultimately, my admiration will always be what it is, even with his pain, difficulties, and what he communicates. Deep down, I think the universe brought him here to ignite inspiration and help us question life in ways we didn’t before. There was an interview where he said, “As artists, people should just thank us.” All I could do was thank him for what he’s done and the inspiration he’s had on me, even with all his challenges.

BRESLIN: I think that’s really well said. I want to go back to the early days a little bit. When you first started dancing and formed your company, how much did illness and trauma fuel your mission then?

JONAS: I think subconsciously, a lot. I’ve always looked to dance and to groups of people that were involved in the arts as a sense of family, or a means for me to release what I was holding on to from my childhood. As time has gone on, I’ve understood why I was doing that and what I’m doing now, and that it’s a somatic practice for me to build relationships with like-minded people.

BRESLIN: Yeah. I mean, your style of dancing is extremely athletic. One of the things that you talk about in the book is that the body is sacred, even though you were battling different insecurities about the new state that you were in with your illness. What did that journey teach you about your body and about your dancers’ bodies, if anything?

JONAS: Sometimes I make dances that are about nature, about the sun or the ocean or wind or certain animals. Sometimes I also make work that’s for me, about pain or trauma or things that are more autobiographical. And this process has taught me a lot, that the dancers and the audience are essentially embodying and witnessing some of those difficulties now. So I’ve been able to step outside and have a little bit more empathy, and be able to communicate more about what the process is going to be like, as opposed to it just being subconscious.

BRESLIN: Definitely. And on a more practical level, in terms of your body, you mentioned that psilocybin has been a huge part of your rebuilding process, but you also talk a lot about meditation and holistic healing through diet, exercise, and discipline. How did that physical rebuilding interact with a more spiritual and creative rebuilding?

JONAS: I’m still trying to figure that out now, because ambitions with work create a pressure and a chase, whereas understanding of self and finding peace within self kind of wants you to surrender to some of those ambitions. So the balance has been my current curiosity. There’s this book called The Body Keeps the Score, which talks about how we store pain and trauma within our body from our past if we don’t resolve it. And that pain and trauma can turn into illness, which is, in large part, what I believe happened to me with Crohn’s and with cancer. I think the more we actually understand ourselves through what we eat and who we surround ourselves with and how we take time to build our individuality, it could actually heal a lot of the wounds that are in us or that are forming in our bodies to create illness.

BRESLIN: Another focal point of the book is, while you’re going through this transformation of the mind and body, you’ve had some time to reflect on our contrived culture of busyness. In the book, you write that everyone’s wedding dress looks the same, and that someone saw you with your bald head and your bald eyebrows and asked if that look was a fashion statement. So what did that reveal to you about our society?

JONAS: Yeah, there was this moment in the book that I wrote about where there was this little girl at an ice cream shop. Her mother came up to me and saw that I was going through an illness, and she’s like, “Can you talk to my daughter?” She was like five and was also battling cancer, and the mom asked her to lift her shirt and show me her scar. So I saw the scar on her stomach, and then I lifted my shirt and showed her the scar on mine. It was a really profound moment. And when you ask that question, I think a lot about how, as adults, a lot of our professional ambitions just become this chase. For me, growing up with divorced parents who argued a lot, I don’t think that adults always understand that the kids are always listening. We’re modeling a life that a lot of people are observing. I think the environment I grew up in makes me question a lot about real-life values, and the values that lead to peace and wholeness. I think overall “busy” and “rest” became bad words for me. It’s not something we should communicate about or aim towards. We should actually be more peaceful, still, and present with those around us. It’s easier said than done though.

BRESLIN: Yeah. I love the way that you kind of reframe some words like “busy” and “rest” in the book to not have such negative connotations, but to think of them as meaningful inactivity. And alongside dance, photography has also been a huge part of your business and your mission with Jonas. The book, while journal entries, is also a series of raw self-portraits before you started treatment, during chemo, and after. What role did photography play in helping you process this new identity during your illness?

JONAS: The man who wrote the foreword, Glen Hansard, is a great friend and artist that I really admire. I went to go see his show many years ago, and he introduced me to his friend named Ezra Caldwell, who was also a dancer. I went to New York to visit Ezra, and he was battling cancer at the time. Ezra showed me that he took self-portraits throughout his journey through cancer, and it was one of the most inspiring things I’d ever seen. When I got diagnosed, something about that just made me think of Ezra a lot, and I wanted to go down the path of almost paying homage to him, but doing the same thing through my perspective and through what my journey was going to become. I’ve always had this curiosity to just document life and think about my flesh when it’s old and wrinkled, and have a desire to look back at images of my body—what it looked like at the time, the scars, without the scars, and the family portraits. I’ve had a lot of loss in my life of great friends, and images of them really helped me process grief and remember them well too. I always like to just document what’s going on and hope that I can look back on those things when those relationships, people, or times are no longer there.

BRESLIN: When you look at some of those photos now, do you recognize that version of yourself?

JONAS: No. It’s weird to see a bald body, and the memories play back when I see them. The book in its current form has become such a professional exercise, looking through so many drafts and versions. Some of those images are very challenging to look at, but some also bring great happiness too.

BRESLIN: I think probably my favorite line out of everything you wrote was, “We’re all just bald heads and scars.” Can you tell me a little bit about what you were thinking when you wrote that?

JONAS: I think it’s kind of similar to what I said about wedding dresses. I read this interview about Steve Jobs, he wanted everyone to have the same iPhone. I think in our pursuit to be so different, we’re really all just the same. That’s why it’s interesting to study nature too. Because when you look at cells, or look at nature there are definitely differences. There are beauties, but the way we all function is really just by water and light and connection. That’s why nudity is also interesting in my work. When you just remove everything, you’re truly just naked. And no matter what words we use and what environments we’ve built or how much wealth we have, it’s all we have. I attended a funeral the other day, and it was so profound. It’s just like this one moment to celebrate somebody’s life. The same is true with a marriage or a birth. Then you place the earth with the shovel on top of the casket, and then it’s done. My relationship to mortality has influenced some of the ways I think now. It’s very delicate and when you remove all of it, all we have is the pain in our eyes and the feeling that we have in our nervous system.