ICONS

Photographer Jerry Schatzberg Takes Us Inside His Archives

While most photographers approach their work through what they see in the viewfinder, Jerry Schatzberg does things a bit differently. Schatzberg, the 98-year-old American photographer and film director, began his career photographing celebrities in portraits that eventually came to define the visual aesthetic of the 1960s (Bob Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde cover art? That was Schatzberg). By the following decade, he’d graduated to film, earning Palme d’Or and Grand Prix nominations for The Panic in Needle Park, in 1971, and Scarecrow, his 1973 feature starring Al Pacino and Gene Hackman.

His approach, he explains, is to first find a human connection, getting to know his subjects before ever picking up the camera. This much was evident when, after joining me on Zoom to reminisce on some of his most beloved photographs, Schatzberg invited me for coffee to get to know me before the release of this article. Whether reflecting on his work with models such as Peggy Moffit and Sharon Tate or titans of music like Bob Dylan, Jimi Hendrix, and Diana Ross, Schatzberg speaks of his subjects as more than mere acquaintances. “It always works better when you know people,” he told me with a grin. “It makes them feel more at ease, and they’ll surprise you with what they’re going to do.” This fall, Schatzberg’s entire archive, featuring his portraits of Jane Fonda, Edie Sedgwick, and The Rolling Stones, among others, has been made available for the very first time thanks to the Morrison Hotel Gallery. To mark the occasion, we asked him to walk us through several of his most iconic images. What emerged was a portrait of Schatzberg himself—an artist so masterful he could make even Andy Warhol jealous.

———

“I’m always thinking of something a little bit bizarre, and this seemed like an interesting way to show a fashion piece. I walked into the park one day with Peggy Moffitt, who was the house model for a California designer. I said, ‘Well, we’re in the park now. What are we going to do?’ We couldn’t think of anything right away, and I said, ‘What do we do in a park? You read, you walk the dog.’ So I got my assistant and I asked him to get me a chicken. And he said, ‘A chicken?! For how many people?’ I said, ‘No, a live chicken.’ So he got me a chicken. It took him about 30 minutes. In New York, you can get almost anything. We tied a string around his neck, and my high fashion model was walking a chicken in the park. I always look for something that’s a little bit odd—something someone would ask a question about. I remember one day I walked into Central Park and there was a woman sitting there with a shopping bag, about 70, 80 years old. I set up my camera, and when I was just about to shoot, she reached into the bag and pulled out a snake, six-feet long. It was a lucky photograph. But you look at a picture like that and say, ‘Oh my god, how’d he do that?'”

———

“I remember there was also a photo of a guy in this series. I don’t remember the main topic, but I know the guy was also dressed in Western clothes, but I don’t know if he had a gun or not. It sort of became two photographs in one series. It just seemed appropriate at the time to do this.”

———

“I was part-owner in a discotheque back in the ’60s, and she used to come in all the time with The Supremes. This is just a shot of her alone, but I also had other photographs of her and The Supremes where they made a circle and The Animals joined them and they were all dancing. The head of Motown was also in this series, Berry Gordy. It’s a photo where he’s dancing with his wife. We had a lot of fun, let’s put it that way. The club was very popular. These people all came down just to dance, and the music was fantastic. We didn’t disappoint them.”

———

“I started photographing Bob Dylan in the ’60s. He used to come down to the club and hang out there with his buddies. I’d also take him to other clubs, and the owners loved having him in there because he was really on the way up, and people loved his music. The press knew he was skeptical of them, and they weren’t very respectful at first, until all of a sudden he became a big star. But they would tell him to do silly things. And he’d put it off on them, telling them, ‘Don’t make me the fool. You’re the fool.’ With Dylan, it started out as a friendship. I asked somebody who was close to him if they could set up a sitting with him and he said yes. Often, I’d ask someone to come in about a half-hour early. We’d go into my office and just hang out and talk and become friendly. It always works better when you know people. It makes them feel more at ease, and they’ll surprise you with what they’re going to do.”

———

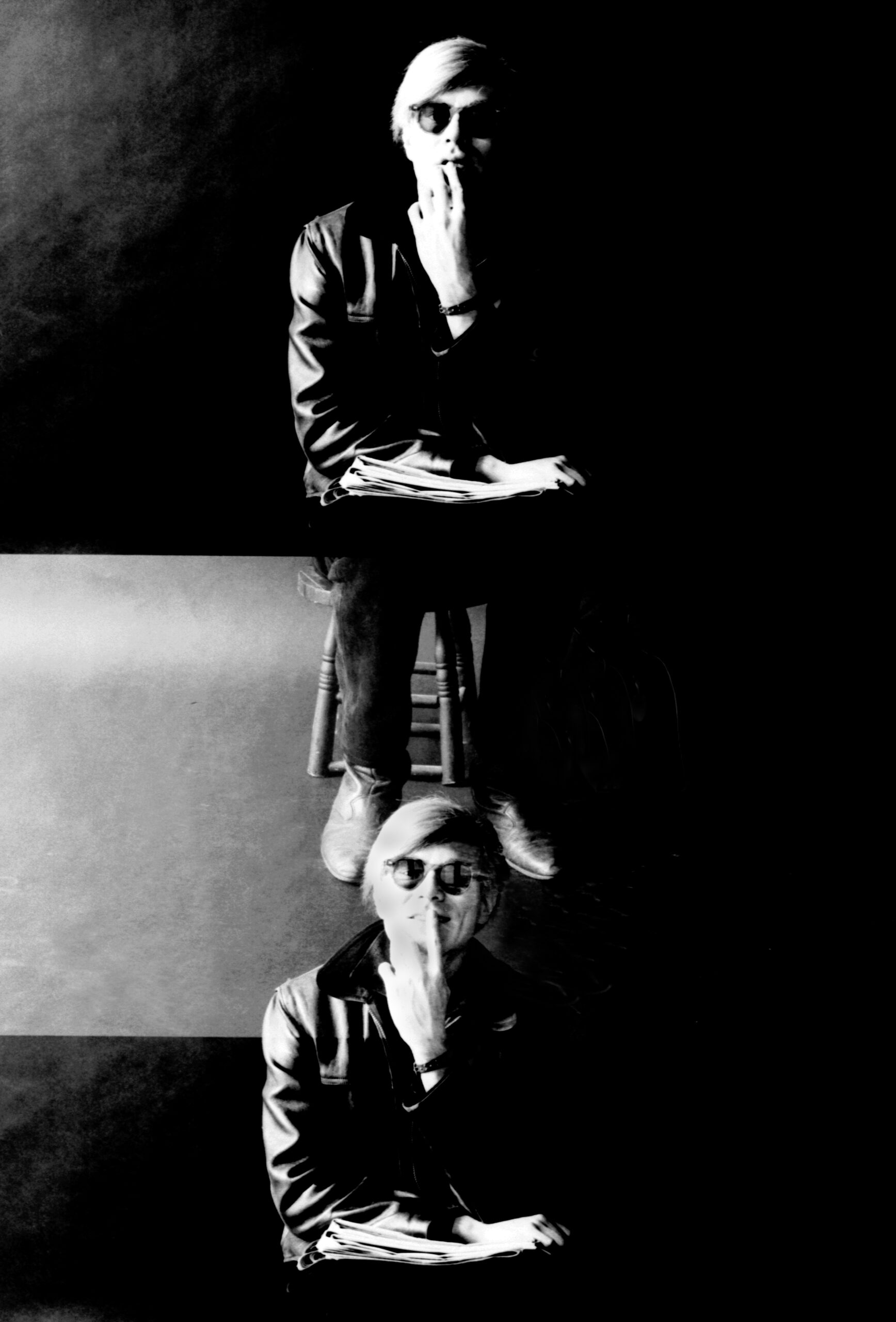

![]()

“That was taken in Manhattan, on the East Side. He was really very cooperative, so we got along very well, and that’s very important if you’re going to photograph somebody. I liked the setting and I liked his reaction to it. And of course, if I look back on my photographs of him, he’s almost always smoking a cigarette. In some ways, this was the beginning of our relationship. Fortunately, he’s got a sense of humor, and I’ve got a sense of humor—sometimes.”

———

“If you mention Charlotte Rampling to anyone, they’d say, ‘Oh, she’s so beautiful,’ and she is. And was. She started as a model, and then she became an actress. I think this was probably taken after she started acting.”

———

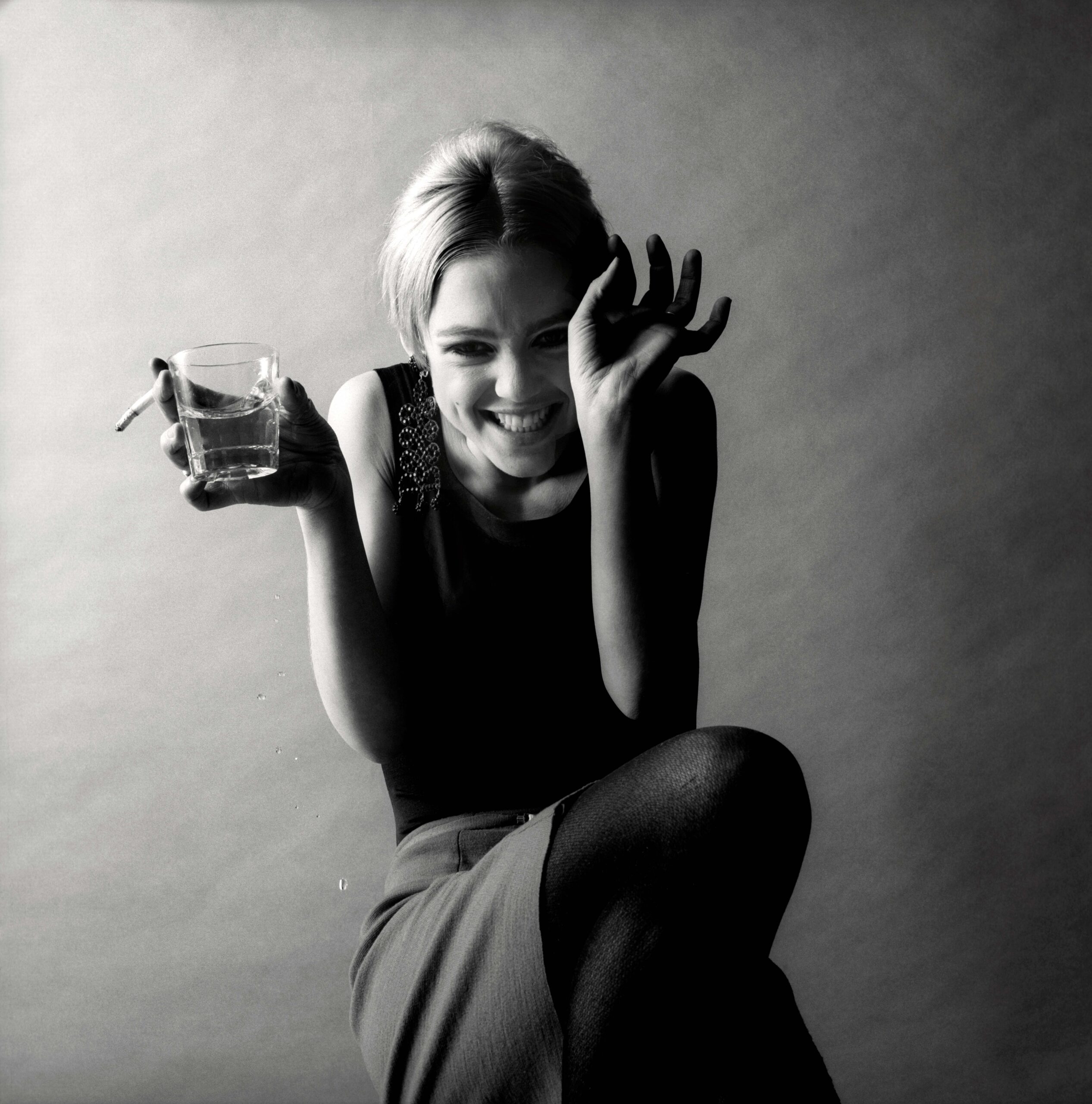

“I had met her before this, and I knew of her relationship with Warhol and all those people. I was just finishing one of my first sittings with Bob Dylan and his manager, Albert Grossman, asked me if I would photograph her. And I said, ‘Sure, I think she’s wonderful.’ Then I was walking in the street and I saw Andy and a female photographer walking towards me and we stopped and we talked a bit. He asked me what I was up to and I said, ‘Well, I’m getting ready to photograph Edie.’ And I noticed that his whole face and attitude changed, because he felt Edie was his property and he didn’t like the idea of other people stepping into where he should be. I felt that this wasn’t really a good place for me to be, so I just left. By the time I got back to the studio, he had called to ask if he could come and photograph me photographing Edie. I guess he felt that made him part of it. So I said, ‘Sure.’ And then another photographer, I forget her name, called and said, ‘Can I come along and photograph Andy photographing me photographing Edie?’ I said, ‘Yes, you can all come along.’ I think 30 or 40 people showed up and they were all in my studio, so I said, ‘This won’t work.’ So I took Andy, the female photographer, and Edie into my dressing room, and that’s where I photographed her. Afterwards, I got tired of all those people in the studio making a lot of noise, so I said goodbye to all of them except Edie. I asked if she wanted to go up to Harlem to see Otis Redding playing at the Apollo, and she said, ‘Yes, of course.'”

———

“The ’60s was a big time for change, and we were lucky to be a part of it. There were some really interesting people. Most of these people were a part of Andy’s Factory group. When I photographed Andy at his factory, it was me taking a photograph of Andy Warhol at Andy Warhol’s factory. This is, if I were to go to Edie’s apartment, to photograph her. It was just something I decided to do. With their permission, of course, because I don’t like to impose if people aren’t interested. But in the ’60s, we had a lot of freedom. The magazines were interested in the photographs, so we had a lot of fun.”

———

“I had met Mick in London, but this was on their first trip to New York. I don’t know how it came about. I think there was another photograph that we saw and said, ‘Let’s do something like that, in drag.’ My studio was right around the corner from this location, so they were in there getting ready. I’ve got a lot of photographs of them putting on makeup and getting dressed. If you can see the star in the window, that’s from my earlier life, when I lived in the Bronx. There was a war on, and if you had somebody in the Army or Navy, you’d put a star in the window. I set it up as an earlier photograph than it was, and then put them in drag. We all loved it. It wasn’t necessarily satire, I told them what I was up to. They loved the idea of being in drag. This is while Brian Jones was still with them, who really started The Rolling Stones. But I think they had some troubles between them, and then Brian left and Mick really became the star. I loved Charlie Watts, who was their drummer. He was a serious drummer. If he came to New York, he went to see all the jazz groups. “

———

“My god, what happened to her? Where are her clothes!? Well, I had been photographing a whole series of nudes, and I thought it would be interesting to photograph her that way. At first she agreed, but then she thought about it and called me to say, ‘I’ve been thinking about it, and I’d rather not.’ I said, ‘I’ll tell you what, why don’t you come in, let me take a picture of what I’m thinking, and if you don’t like it, we don’t have to use it. But if you do like it, we use it.’ She came, we did these pictures, she loved them. So that’s how that happened. People always think that if you get somebody that’s popular and you take their clothes off, it’s better. It is and it isn’t. It depends on the personality, but she’s so wonderful. If I gave her a daisy, she’d know what to do with it. She did the whole setting up. I don’t think there’s anything wrong with any nude photographs if they’re taken properly.”

———

“There was a Beatles cover made, and Frank Zappa saw and liked it. I didn’t know him, but I guess he knew some of my work and he called me and told me what he was thinking of. He said he’d like to do something like that. Now, the entire photograph, you have artwork on the top part of the photograph, which doesn’t show up here because it was the basic photograph. Then he said, ‘Why don’t we ask Jimi Hendrix to come and be in the photograph?’ So we called him and Jimi said, ‘Okay.’ I think he had just come back from England. Next to Jimi is Zappa’s wife, who was seven or eight months pregnant, as you can see. Zappa’s group liked being in drag, and I think it worked out. You should see the finished cover. This is just half-finished.”

———

“It’s always sad looking back at these photos now, because she was absolutely wonderful. She was so great to work with. She was so great as Roman [Polanski]’s girlfriend. I met Roman when he first came to New York and I photographed him. I first saw him at the Lincoln Center. I had broken my leg and I hobbled over to him and told him I’d like to photograph him. He looked at me, looked at my leg and he said, ‘Okay, let’s go.’ I took a few photographs at the Lincoln Center, then I made an arrangement where he and his producer and a few other people came to my studio. I was friendly with him right from the beginning. As a matter of fact, I used his cameraman in about four of my films. I wasn’t sure about his work yet, so I called Roman, who gave him the highest recommendation. That started a very nice relationship between Adam Hollander and myself.”

———

“He was in his dressing room, and I saw him go over to the mirror that was hanging on the wall. He started combing his hair, and I thought, ‘That would be a wonderful photograph.’ And now I think it is a wonderful photograph. If you take the mirror out, you don’t have any photograph. Just blank space, and then an abstract shape on the side. But with him looking in the mirror, it lets everyone think of what they want. Maybe it’s ego, maybe it’s just wanting to be sure that his hair is okay, maybe it’s just wanting to take a last peek before I start to lionize him. This was at Forest Hills Stadium. He was just getting ready to go out, and he didn’t know I was going to take the picture. I saw him wanting to have his hair in place and see what all of his buttons and beads were. In a way, it has something to do with ego, because we all want to have our hair combed properly and our lipstick the way it should be, but I think that’s a very innocent and wonderful photograph of him.”

———

“This was a still from the film [Puzzle of a Downfall Child]. I worked with models for quite a while before I started making films. I had been very friendly with one of my favorite models, Anne. She got ill once, and I went out to take care of her. In that meeting, I learned a lot about her, about her childhood, what she went through in different times, and I really liked what she had to say. I asked her if I could just tape her and she said yes, and a lot of what we see in the film I did with Faye is basically Anne’s life, when she was younger. It was a film about models and my relationship with them, and how I’d act with them. I don’t work with that many models now because I’ve started to make films, so I’m with actors more. But actors have a certain way about them, models have a certain way about them. Certain things are expected from each. A model is expected to look absolutely beautiful all the time, and I think Faye didn’t have a problem with that. She always looked beautiful.”

———

![]()

“I think that was taken at Radio City. I was just there, photographing what was happening. I saw this little girl looking at me, and I saw the whole set-up of the balloon. I just had to take the picture. I was doing street photography early, because when I first went looking for a job, the guy that I went to see had an ad in the New York Times for a photographic assistant. He said to me, ‘Well, what camera do you use?’ I said, ‘I don’t have a camera.’ He says, ‘You want to be a photographic assistant and you don’t have a camera?’ I said, ‘I don’t yet. Would you recommend something?’ And he recommended a Rolleiflex. It was very expensive for me, but I borrowed some money from my mother to get the camera. And once I got it, I just started walking the streets and recording what I thought was interesting.”

———