Nigel Cooke’s Emotive Drive

PORTRAIT COURTESY OF PACE GALLERY, LONDON.

London-based painter Nigel Cooke’s abstract figurations create mazes for the mind. Looking at his large-scale surfaces, the viewer becomes entrapped by illusionary depths: windows are blackened, inviting the viewer to question what lies behind; a frozen waterfall, when viewed from afar, becomes a skull; flowers become ashes; and tree branches become veins. Suddenly, however, the presence of an oversized bird or unintelligible book abruptly interrupts wandering thoughts, bringing the viewer back to reality. “Black Mimosa,” the artist’s current exhibition at Pace Gallery and his first in more than two years, introduces an explosion of color as well as certain absences, yet retains Cooke’s signature dark undertones.

“In a way, it’s about renewals, being able to take something to the brink of destruction,” Cooke explains.

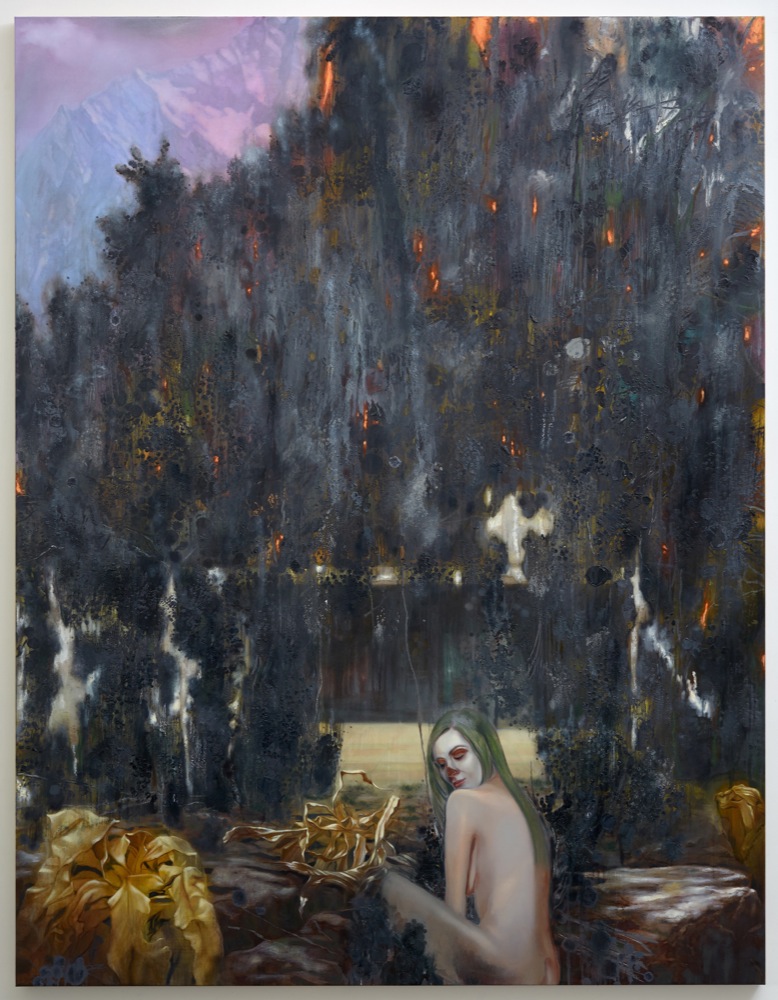

In the exhibit, Cooke shifts away from narratives and towards purely emotive and gestural works. He showcases his ability to present the positive and negative, oftentimes infusing both emotions within one painting: Mimosa, a painting swirling with canary yellows and a delicate figure, is dedicated to his three daughters, but it hangs opposite The Temptation of St. Anthony – Black Mimosa, a dramatic image of a young temptress surrounded by what appears to be a cloud of blackened ash. The only concrete elements of Cooke’s paintings are the occasional birds and figures, which appear nude or wearing creations of the artist’s mind, erasing any element of time.

“The paintings are kind of set in the past, present, and future all at once,” Cooke continues. “I’m trying to get that multi-temporal feeling; it could be happening now or 100 years ago.”

Cooke received his Master’s from the Royal College of Art and his Ph.D. from Goldsmith’s College. In 2013, he released a condensed and edited version of his dissertation as the book Words, and now, “Black Mimosa” marks his debut with Pace (he was formerly represented by Andrea Rosen Gallery). When he was in New York for the installation process, we met Cooke at the gallery.

EMILY MCDERMOTT: You were exhibiting every single year from 2004 to 2013, but then you had this two-year gap.

NIGEL COOKE: I wanted to test the work and my images and ideas. It’s almost like when you’re painting you’ve got two lives: You’ve got your own development as a person, and then you have this other thing. There are certain times when a painting accelerates beyond you, and you have to try and understand and catch up with it. This was one of those periods, especially joining this larger gallery. It was a moment for me to say, “What kind of paintings do I really want to make? What’s the ultimate combination?” I felt like I had reached the end of a period of life, where the work was jumping about and pushing something new every time. I wanted to dial it back and create a language that was stable and deep. I wanted my relationship to it to be quite profound; I didn’t want to think about exhibiting. I thought, “I just want to be isolated and make my own thing in secret,” to not be results-conscious, to let the paintings talk and become what they are.

MCDERMOTT: So this exhibit wasn’t planned when you started making these works?

COOKE: I had no idea. What happened, is that this painting, Books in Snow, was a whole year, start to end. It was like a battleground, coming after several failed paintings I destroyed. The complex thing is that my stuff thinks in its inception; it has an autobiographical driver. A little thing in life will set something off—maybe seeing books in the snow, or a bird, or thinking about being an artist, someone who’s trying to consider age, change, development, and maturity, and what that means when you’ve been making paintings for 20 years. Small thoughts grow into a picture. It may suggest an individual or it may suggest a place, but generally the painting’s job is to work that [idea] into an abstract proposition that is completely removed from the starting point.

In a way, what I’m interested in is where you end up. How do you make a painting that is like thought? So that it generates its own reality and leads you to learn something new? It’s quite poetic, a bit like film and poetry—how you can make these huge leaps of location, reference, reality, and consciousness. How do you paint the inside on the outside of a person? How do you paint an abstract painting that happens to be a figure? How do suggestions engage somebody else and make them think about larger things—mortality, consciousness, and our place in the world? Using painting as a metaphor for consciousness is what I’m interested in. Like Blind Philosopher, it’s the word on the wall next to it that says “Blind;” you can’t get that from the painting. It’s a linguistic add-on.

MCDERMOTT: Do you think about all of the different senses when you’re painting?

COOKE: Yes. What are your sensory priorities when seeing a space, and how does it become a space for strangeness? It’s the strangeness that I’m interested in, when it becomes uncanny and bizarre. In some ways, it’s just a portrait in front of a tree.

MCDERMOTT: But it’s so much deeper, especially with the still life in the corner.

COOKE: I think that still life, in thinking that this person is a philosopher, it’s saying there’s a platonic reflection about the birth of representation. But there’s an isolation because it’s not actually there; the person [the Blind Philosopher] can’t see it.

MCDERMOTT: It’s also interesting that her pupils are different colors.

COOKE: Little things like that, they’re intuitive. You think, “Okay, this suggests a lack, this divergence of pupils.” Who knows why it happens, but you just follow it. A lot of my work is intuitive like that, letting the abstract things create what the painting is, even if it happens to be a figure.

MCDERMOTT: There’s no figure in Books in Snow, though. How did that happen?

COOKE: It had figures originally and then it grew. In the end, the painting led me, and it became a painting about absences. There are these books, which you can’t reach or open; there’s a sort of spatial absence. There’s no figure, but there’s this building with a face. There are absences, but there are also presences. It’s about how painting can evolve its own abstractions. I didn’t know the painting was going to be about that, but it has to have that journey; I have to learn something, I have to end up somewhere I didn’t expect to be, otherwise, I don’t think it’s painting. Painting, for me, you want to get to that feeling like they’re prehistoric, like they’ve always existed and you just found them.

MCDERMOTT: I want to ask about the paintings Mimosa and Temptation of St. Anthony – Black Mimosa, which is also the name of the show. What does “Black Mimosa” mean to you?

COOKE: Mimosa and Black Mimosa are sort of a combination, the dark and light version of the same idea. The positivity of the plant, when a mimosa flowers, is short-lived. It comes out in spring; it’s very yellow. In Italy, men hand mimosa flowers to women for Women’s Day, like Valentine’s Day. It’s the flower for Women’s Day, based upon the celebration of female contributions to the Second World War.

So there’s an anecdotal side: I have three daughters, we were on a trip, and saw these mimosas in all the offices. I loved the color, and it became a tribute. If the flower has been appropriated to represent women in some massive way, then I thought, “Well, I’d like to localize that for myself, have it as a flower to celebrate that side of my life,” which is actually the center of my life, them.

Mimosa is quite straight in a sense, quite a joyous celebrative thing, but then, of course, as the painting develops, it moves away from that. The flowers are scale-less; they could be microscopic views of mimosa flowers or they could be very distant trees. In a way, it’s like a Parisian, European, Pre-Modern idyll; it’s like I almost wanted to paint a Van Gogh painting. The figure is the contemplation of that, representing that contemplation through a persona. It’s quite hard to talk about, really. It’s very visual. I’m trying to reach something that’s intoxicating to me, whereas Black Mimosa was the idea of that being scorched, and a risk with adding the Temptation of St. Anthony theme.

That story of St. Anthony is testing faith, being deserted, learning about what matters, being seduced by visions of alternate things—riches and seductions—and coming through the night of that temptation. By beginning this group of paintings and joining Pace at the same time, I felt like that’s what I was doing: testing my faith in what I did and going away in the wilderness to see if I could survive it.

[In Black Mimosa] it’s like the mimosa is a desecrated symbol turned to ash. The female figure in that is like the young seductive siren who tries to draw St. Anthony away from his faith. It also transmogrifies into a skeletal image of death. The makeup on the face is a skull with a young face behind it; it grows into both things, it’s a place of renewal. Some people feel [the paintings are] negative, nihilistic, or apocalyptic, but I never see any of that. To me, it’s just that point of transformation, which is actually really positive.

MCDERMOTT: It’s like the phoenix rising from the ashes.

COOKE: Exactly. And that’s what creativity is, really: It’s taking yourself to the point at which destruction, creativity, and creation are interchangeable.

MCDERMOTT: I read that you usually have an image in your head when you start a painting, but you keep mentioning the journey that a painting takes you on. So what is the original image you begin with?

COOKE: It’s funny. It comes into my head readily complete. Obviously lots of changes go onto it, but the first thing that comes into my mind has a crisp identity, something very strong and solid. Then I have to find a way to engineer it. I find sitters to pose for the figure sometimes, I set up still lives or bits are created with foliage, observing, and drawing things, it all comes from these different sources.

The paintings don’t exist outside themselves. There’s no lead photograph off the internet or anything like that. It all comes from my mind and it’s a bit like a little movie each time—how do I get the props, the setting, the time of day, the light, the action? What’s the figure like? How old are they, what are they doing, what are they made of?

MCDERMOTT: Your process is very physical. When you’re in the studio do you become entirely immersed within a painting and work crazy hours? What’s it like separating your studio and family life?

COOKE: It’s something I’m trained in. I’m not very random. I keep regular hours and create habits so that it’s not too impactful either way. Only at the very end does it become insane long hours, around the clock sort of stuff. The key, really, is to live with paintings. I never work right up to a show. I have a month or so to reflect on things, seeing if they survive.

I think it’s really important not to put too many paintings out there. When you first start, you show whatever. But I think when you get older you’re more alive to the possibility that your views may not be the most important; your view and value of it may not be the key. The paintings seduce you, even if you’ve just got a little bit of skill, you can get hooked on what they look like; you’ve got to allow that to evaporate and live with what the thing is. Sometimes, when the skill is less than, the image is more interesting. Sometimes it can be highly rendered, but facile.

MCDERMOTT: When you went into your studio to refine and refocus, what did you learn most about yourself, your process, and what you want to do?

COOKE: I really wanted the paintings to be less verbose, to communicate less. I also wanted to clear out devices I’d relied upon. I think there had been a weirdness to the images, like eyeballs and fried eggs, and there’s a communicative side to that, which was really important to me. This devalued iconography, the joke-shop iconography, like an eyeball, I’ve always been fascinated by, because everyone can relate to it. It’s bizarre, but also familiar. I’ve always liked that as a vessel for relating more unusual things. Yet with this, I thought, “I don’t want to rely on anything familiar. It has to be blank.” Knowing what was going in [the paintings] was something I wanted to get away from… I don’t need any tricks; that’s what I did, I let the tricks go.

In a way, I learned that I was hiding behind things. The whole St. Anthony thing has been about, “Stop trying to reach out, just do it for yourself. Let it just be and see what that looks like.” They all link into the way I am in the world—the fact that I’m a quiet person, I’m not a flashy art world person. I’m in the studio in the middle of nowhere. There’s sheep and fields. The work has to be authentic in that way.

What really surprised me was how strange my paintings are anyway. To me, it’s like, “Let’s paint some portraits and some objects. Don’t make it weird, just make it dead straight,” but it’s still weird. I don’t know why. [laughs] I guess it’s just the way I see things.

MCDERMOTT: Can you tell me about Black Butterfly?

COOKE: In my head, this is almost about someone jettisoning a version of themselves off a balcony. That idea came to me before this sequence started; I tried a version of it a year before and it didn’t work, but the idea stayed with me. I was also interested in the butterfly shape, the vaguely symmetrical sides. My daughter found butterflies in the garden shed and they took off one day. It was a beautiful thing, a strange transformation. I was trying to yolk together those two kinds of transformation. They don’t go together, the only place they go together is in your head, so the question is, “How can the painting do that and also not be too strange, not fantasy, still be grounded and convincing and solid?”

MCDERMOTT: In 2013 you said something about anxiety being the most important element of abstract figurations. Do you still feel that way?

COOKE: I think there’s still a twisted nerve, an interest in the awkwardness of existence. Awkwardness is what I would call it, rather than anxiety. I want there to be that little edge everybody feels. The moment is never perfect. It’s like that right now—in my head I’m being super lucid, but you never are. You’re always fumbling.

A lot of people invest a lot of money and time pretending life isn’t like that, but it is for most people. I’m trying to get that vulnerability of what it feels like to be human. My images, I think, try to be vessels for that—whether it’s to do with love, self-criticism, failure, exaltation, or age, it’s always that vulnerability. The terms of your reality have suddenly reversed on you. You get caught in the rain, you fall over in the street, or lose your wallet—there’s constant assaults to your dignity. [laughs]

MCDERMOTT: Who was one of the first artists or pieces of artwork that you saw that really solidified your interest in painting?

COOKE: It was Francis Bacon. A lot of young people like that work; it’s quite angsty and on the edge. I find it magical, this real presence of the uniqueness of the vision. I was spellbound by the idea of living with something that you make, that’s like a character, but a thing in the world that’s got it’s own life. It’s also the limits—I really like the rigor of the fact that it’s a figure every time. And the abstraction too, the fact that everything is in service of the painting. What’s key is the painting itself; any truth is only through the painting. There’s a certain triumph to that. I always felt that the license of the artist is taken by Francis Bacon. You’re able to say, “It has nothing to do with you as a sitter. It has to do with me making this painting.” That was inspiring for me, just the attitude.

MCDERMOTT: You wrote Words and received a Ph.D., so writing has played a large role in your life. Did you find yourself writing while making these paintings?

COOKE: For these, I wanted to move away from that. It’s almost like learning a language, knowing it, and then being like, “Okay, I really want to be intuitive.” These are ultimately visual things and what I like is that they’re much harder to talk about because they don’t have that linguistic driver anymore. They’re much more about emotional drivers. I must say, I’ve always felt myself as someone who can walk into a show and start talking about what I’ve done. This one is not easy to do that. It’s quite nuanced. There are things that inform the works, but that doesn’t go anywhere near what you’re actually looking at.

“NIGEL COOKE: BLACK MIMOSA” WILL BE ON VIEW AT PACE GALLERY, NEW YORK, THROUGH OCTOBER 24, 2015. FOR MORE ON THE ARITST, VISIT HIS WEBSITE.