EXPATS

Leif Randt and Vincenzo Latronico Compare Notes on the Millennial Berlin Experience

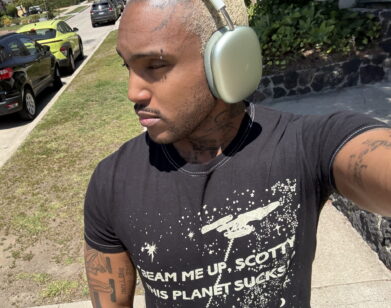

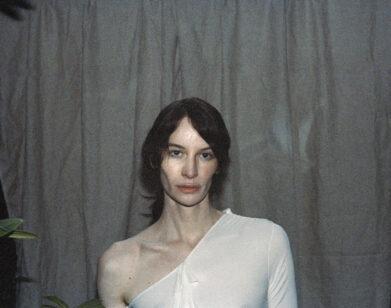

When the authors Leif Randt and Vincenzo Latronico got on Zoom last month to talk about their respective books, Allegro Pastel and Perfection, they weren’t quite sure if they’d met before. “Our social circles overlapped a little bit, but only marginally,” posited Latronico, the Italian writer whose novel was shortlisted for the International Booker Prize. That sort of elbow-rubbing among artist types happens quite a bit in Berlin, which, for the most part, is where the both their novels of modern millennial malaise take place. “We see each other in nightclubs,” Randt replied, “but often there is not necessarily much contact.” His book Allegro Pastel, the English translation of which came out in the U.S. this week, follows the long-distance relationship between Jerome, a web designer based in Frankfurt, and Tanja, a mercurial Berlin-based writer on the heels of a successful debut novel. Perfection, meanwhile, conveys contemporary Berlin in microscopic detail, telling the story of another pair of self-professed creatives, Anna and Tom, against the backdrop of a city inundated with striving expats. It only made sense, then, to convene the two authors for a conversation, where they got to talking about the Americanization of Europe, depicting the internet on the page, and writing in translation.

———

VINCENZO LATRONICO: I really liked your book.

LEIF RANDT: Thank you. I liked yours too. I just read it last week and gave it as a present to my brother-in-law who turned 55 on the 5th of May, which I thought was a very special date. I was at the bookstore and I thought, “What will I give him?” And then I thought, “Perfection is a nice one.”

LATRONICO: Thank you. Wow.

RANDT: We’ve never met, right?

LATRONICO: No, I don’t think so.

RANDT: Maybe randomly somewhere.

LATRONICO: Our social circles overlapped a little bit, but only marginally.

RANDT: Yeah, maybe. Like, it’s typed out in Perfection’s pretty nicely, how there’s different scenes in Berlin. And for some reason, expats and Germans don’t necessarily cross paths. We see each other in nightclubs, but often there is not necessarily much contact. When did you come to Berlin?

LATRONICO: I came in 2009.

RANDT: Same year.

LATRONICO: But that thing that you mentioned is especially [true] because of language. In the art world, there is much more overlap. But in order to meaningfully participate in the literary scene, you have to be able to read the books. And as a matter of fact, I think that yours was one of the first books I read in German, even though I had been living in Berlin for 10 years by then.

RANDT: I have friends who’ve lived here even longer and they don’t speak any German. Did you read it during the pandemic?

LATRONICO: Yeah, during the pandemic. When did you start writing it?

RANDT: I would say one of the first ideas was the character of Jerome Daimler, a guy who’s in a creative field but who doesn’t move to Berlin. What happens to someone who is so focused on culture and the creative field, but who doesn’t leave his home village? Jerome Daimler was there first, but I didn’t come far with this project. It opens at the opening of a special grocery store where there has been discourse in different directions. Right-wing people were against it, left-wing people were against it, and he goes to the opening. That was the opening of the opening scene, but this didn’t lead me to anything. All of a sudden, I was walking around in the heat of Beijing in August 2017 and I thought he should have a girlfriend in Berlin who’s a writer. I had the character’s name already—Tanja Arnheim. A bit after this China trip, I started writing properly. So the actual writing process was between 2018 and summer ’19, pretty much what the dates of the book’s narration are as well.

LATRONICO: I started writing the first idea of my novel in 2019, but most of it I wrote in 2021. The Berlin I had in mind was the same Berlin that you write about, which had been frozen by the pandemic. It was the Berlin of 2018 and ’19. What I’m getting from some readers, now that the book came out in English, is that this feels like a document of another era. My book came out in German one week before the invasion of Ukraine. And in some ways—I don’t know if you get the same feeling—I look at these characters and I’m like, “Man, you’ve got no idea how lucky and enchanted and privileged your bubble is.”

RANDT: Absolutely.

LATRONICO: “It’s about to get much worse.” But I’m also very conscious that we are two white, middle-aged guys talking to each other and saying how better the city was when we were 20.

RANDT: I have mixed feelings about better or worse, but…

LATRONICO: What strikes me also is how much of the life that you are describing in your memories of Berlin, but also in the case of my characters, was made possible by low rents.

RANDT: Absolutely. I was going to university between 2004 until 2009 in Hildesheim, which was nice for me because it was two hours to Frankfurt back home and it opened up the north of Germany for me. On the other hand, it was pretty shitty and could be seen as depressive, because it was a rather poor city. Now I see some beauty in it when I revisit, which doesn’t happen often. But back then it was the case that Hildesheim was a bit more expensive than Berlin. For my room, I paid 300 Euros. It would be cheaper in Berlin. You knew as a student, “I might go to Berlin so I won’t need to make much money and I can make a living.” This whole concept of what would be possible in life as a culture worker, so to speak, was based on the city existing the way it existed. The two of us, we’ve been lucky enough to do okay as writers. But sometimes, people were trapped in a lifestyle that didn’t work out ten years later.

LATRONICO: The life that you’ve built seems like a solid, normal Berlin lifestyle, then all of a sudden the owner of your sublet moves back from Malo and it’s too late. Or you never subscribe to the Krankenkasse and now you get pregnant and you have to go back. Did you want to give an impression of Berlin in your book? Was that one of your concerns?

RANDT: Actually, not so much. First of all, I made the decision to focus on places that I’ve actually experienced. My novels before were kind of surreal—one was even science fiction, and everything was in parable form. Then I thought, “Okay, let’s talk about the obvious. Let’s try to write about my hometown, and about Berlin, because I’ve been living here for more than 10 years now.”

LATRONICO: Did it bother you that, at least in my understanding, the book was received as this big portrait of Berlin, even though only one of the characters lives in Berlin?

RANDT: I would say less than 50% of the scenes happen in Berlin. But Berlin grabs more attention than other places, which can be very annoying. I thought it might be my most popular book, because it’s the most relatable, and saying it’s a love story between Frankfurt and Berlin, people might be able to relate. But I didn’t anticipate this mainstreaming would happen about this laid-back story.

LATRONICO: Are you getting the same reading from English readers?

RANDT: There’s been two reviews—one was negative and one was positive. I haven’t read the negative one yet. But The Financial Times was very positive. But I haven’t spoken to so many English readers. I was in London last weekend, and so I met maybe four people who have read the book and they were all from the publishing house. So I can’t really tell.

LATRONICO: Ah, yes. . I was asking about this because when my book came out in Italian, this was three years ago, it was read as the story of these two Italians who emigrate to Berlin. The role of Berlin is very central. It’s seen as a reportage from an exotic life of an expat working culture. But in many ways, Berlin is almost incidental. It’s a story about a very curated, digitally-facilitated lifestyle that can happen in Berlin or in London or in Stockholm or in Barcelona. In this instance, it just happens to be in Berlin.

RANDT: You could tell a similar story in London, Paris or New York, but I would still say Berlin was loaded up as a cultural epicenter because it was affordable.

LATRONICO: Yeah.

RANDT: Stuff was created that was not created anymore in these other cities. Now, returning to London, where I did exchange studies in the 2000s, I was thinking, “I don’t care about Berlin so much anymore.” As a German, it wasn’t as exciting. It was a city I could travel to in two train hours from my university town. All my colleagues went there. It was the obvious choice. I fancied East London because the aesthetics back then were quite different from Berlin, which is not the case anymore. There were fashion choices you could do in London that you were appreciated for. You would be laughed at in Berlin because it was more conservative and minimalistic and not as eccentric. What happened when I returned to London was I saw neighborhoods that had been exciting and are now really established. There’s so many kids and rather bourgeois people. Not exciting anymore, and very cleaned up. When I returned to London I thought, “This is not my London anymore.” So similar structures happen, but I think in Berlin from the ’90s to the 2000s to the early 2010s, that was the most extreme. It’s more extreme than even the development in Paris.

LATRONICO: Yeah, definitely.

RANDT: You grew up in Rome, right?

LATRONICO: I grew up in Milan. But not all expats are the same, right? Because the ones who work in English somehow feel more at home than the others.

RANDT: That’s an interesting aspect in the book—this Americanization of 2010s. I felt this culturally as well. Because during the 2000s, before Spotify, you had this library of MP3s. I recognized at some point there’s a lot of British music here. Nowadays, I can’t say where the music comes from. This is a digital era now. In the 2010s, I realized there was way more American influence, especially TV series. Everything came from California. The 2010s were so heavily influenced by the United States more than anytime in my life. In Berlin as well, in my neighborhood, bars opened by American owners and most people who came to the city were American. Nowadays, you go to the movies at Rarbach and you barely hear anyone talk not in native English.

LATRONICO: We were talking at the beginning of this conversation about why didn’t we cross paths more often in Berlin. Somehow, literature resists this.

RANDT: True.

LATRONICO: Because visual artists and musicians can live in Berlin speaking bad German, bad English. But if they make good art and good music, they participate in the scene.

RANDT: No one will care.

LATRONICO: Whereas, as an Italian writer, I gravitated towards the English-speaking literary world just because I could read their books. But of course, they could not read mine.

RANDT: This is why it’s such a relief to be finally translated into English. Now you can show your work to people who you’ve been friends with for many years and they haven’t read anything. On the other hand, it’s kind of scary because then they might find out that they don’t like my writing. But before they always expected to like it. It’s a nice thing.

LATRONICO: Yeah, this happened to me actually. For years I’ve had this group of writers who lived around Charlottenburg. We’ve been hanging out for a long time. Then I was like, “Oh my god, now they’re going to read my book.” This is when I realized how the figure of the expat is actually built around the American. There was a moment in Berlin in which, as an Italian, I was like, “Even though my German is good, and I do my psychoanalysis in German, I’m not one of the Germans, but I’m also not—”

RANDT: In the expat scene.

LATRONICO: Yes. I’m not in that conversation.

RANDT: Do you remember HBC at Alexanderplatz [a cultural hub that opened in 2009]?

LATRONICO: Oh, yeah. Of course.

RANDT: It was peak in 2009. I remember these random meetings of people who then mentioned, “I’m from New York.” Everyone was always surrounded by these cool Americans, and I was proud of knowing American people. No one cared about all the Spanish people around.

LATRONICO: Yes, exactly.

RANDT: You were never annoyed by English-speaking tourists because then you could better your English by hanging out with these native speakers. The sentiment about this has changed, luckily. But that’s why I don’t feel so nostalgic about this magical, easy Berlin that I’ve moved to because for some reason, I don’t find it so cool. If I see the edgy new kids scene nowadays, I find this cool. This is not my wave anymore because I’m too old and I’ve been here too long. But I can appreciate it in terms of the aesthetics. In terms of the aesthetics of contemporary Berlin, I like this better than 10 years ago. I remember my girlfriend complaining about it a couple of weeks ago, but she just moved to Paris, so she wanted to find a reason to complain about Berlin to make it easier to leave, I think. But now, since it’s May and the best weather, this very optimistic time of the year, I feel happy in Berlin at the moment. How about you? Where are you right now?

LATRONICO: I’m currently at a friend’s place in Torino because I had meetings here. But I moved back to Milan and I must say, I’m quite happy about that. I’ve served my time in Berlin.

RANDT: When did you move back?

LATRONICO: Two days before October 7th.

RANDT: Oh, wow. You only missed struggle in Berlin.

LATRONICO: I completely missed the transformation of the cultural discourse in Berlin. I’ve just perceived it from afar. At the beginning it was quite terrifying, to be frank.

RANDT: It was a very dark time, I would say. I was celebrating my 40th birthday two weeks later. I considered not doing the party because it was not party vibes. I have Iranian friends there, I have Jewish friends there, I have anti-Deutsche, I have left-wing Germans. But it turned out to be very nice. Everyone wanted to have a distraction from this discourse. It’s nice to go to the real world sometimes, because often trouble is not as heavy if you look it in the eyes instead of sitting in front of your phone watching people argue.

LATRONICO: Speaking of that, I’m often frustrated by how technology is depicted in novels. I have this impression that often writers would like to set stories in a generic 2010 in which people have email, they have some social media, but not too much. It felt frustrating because often, you either have books that are amazing but really specifically about digital life, such as Patricia Lockwood’s [No One Is Talking About This]. Or you have books that put this haze around what stage of technological development they’re in. Your book struck a good balance in depicting digital life. Did you think about this?

RANDT: Kind of. It came out by trying to write accurately about contemporary time from a certain angle. The most important moment was when Tanja is in a night club and she’s high.

LATRONICO: That sequence is amazing.

RANDT: What she enjoys the most is texting with her boyfriend. Some people read it as a problem and I think, “No, it’s not. It’s just a matter of fact.” It’s the reality that you have these gadgets with you and you have the option to communicate. I remember myself being high in nightclubs in the year 2013, and texting on my very old phone. I was using a very old phone until 2016, and then I opened myself up to the internet. My first social media was Snapchat in 2016.

LATRONICO: Well, that’s a crash course.

RANDT: I was amazed by this option to do “stories.” I remember when I showed it to friends and they were saying, “Wow, I wish we had this while we’re teenagers.” I felt really young and fresh, early midlife crisis vibes.

LATRONICO: That’s funny. Now, we are used to associating even the word Facebook to a cesspool of AI generated content and anti-vaccine boomers and data being siphoned off to be used for right-wing propaganda. But there was a time in which Facebook was incredible. I loved Lauren Oyler’s book Fake Accounts, and she’s also a very dear friend of mine. But I wonder how you feel about specifically American depictions of Berlin. There have been quite a few also—Calla Henkel’s Other People’s Clothes, and so on. For a while, I felt that the American vision of Berlin was the dominant narrative of the city internationally.

RANDT: So it would seem.

LATRONICO: As an Italian, I felt some resentment that this depiction of the expat Berlin really glossed over everything that was not coming from that experience. For you, as a German, it must have been weird.

RANDT: Yeah, it has been. It’s the perspective that is the most important because most people can relate because everyone can speak at least a little bit of English. It’s this attitude and confidence that comes with people knowing they will be understood by everyone. Sometimes I get angry about it. But on the other hand, the United States and English-speaking countries have given me a lot as well.

LATRONICO: Of course.

RANDT: There’s even a certain degree of envy toward Americans who can talk about Berlin and be listened to. The world listens. There are so many German people who talk about Berlin and no one cares.

LATRONICO: I had this experience in 2012. I was living in Berlin for a few years, and my second novel came out in Italy. It’s a novel about financial speculations that take place in Milan. I desperately wanted to publish it in German because I lived in Germany. I met this publisher and I gave him the book. He read it in Italian and he said, “I liked it, but we’re not going to publish it because the German audience, when they imagine a story of ambition and financial speculation, they imagine it taking place in Frankfurt or in New York. It’s not a story that they imagine in Italy.” Then the publisher said, “The chapters in Venice were amazing. Why don’t you write a book about Venice?” I gave it a lot of thought. And it’s also partially why the only thing that you know about my characters in Berlin are that they are not German and that they’re not American. You don’t know where they’re from. Some readers assume that they’re Italian.

RANDT: They could be Spanish or Portuguese as well.

LATRONICO: I tried to find a story that was wider than Venice. When I was 20 and 25, Italian literature was not translated unless you were a super bestseller. Then the [Elena] Ferrante phenomenon happened and Italian writers of my generation started being translated. Claudia Durastanti was one of the first. I definitely benefited from this wave. But now that I’m back in Italy, I realize that German literature is not as well-read in Italy as Italian literature is in Germany. Many Italian writers in their 30s and 40s, even if they’re not very successful, they’re translated into German. Do you think that you are part of something that is happening to create a closer look at German literature?

RANDT: I can’t tell. I have no clue. I guess the reason for Allegro Pastel being translated is that there’s a lucky circumstance about people working for Granta Magazine who happen to live in Berlin. They’re traveling between Berlin and London, and could maybe understand the book better or feel it better because they were able to read it in German. German literary audiences are interested in authors from many countries. The book market is diverse in that sense. If you go to a German bookstore, I’d guess 50% of the books are translations.

LATRONICO: In Italy, it’s even more than that.

RANDT: Even more? Wow.

LATRONICO: I guess we have to come up with something sexy and memorable to end this.

RANDT: Something not as dry as the book market. But for some reason, even compared to a couple of weeks ago, I feel kind of optimistic. Maybe it’s just the season?

LATRONICO: That’s May optimism. The rebound from winter depression.