XXX

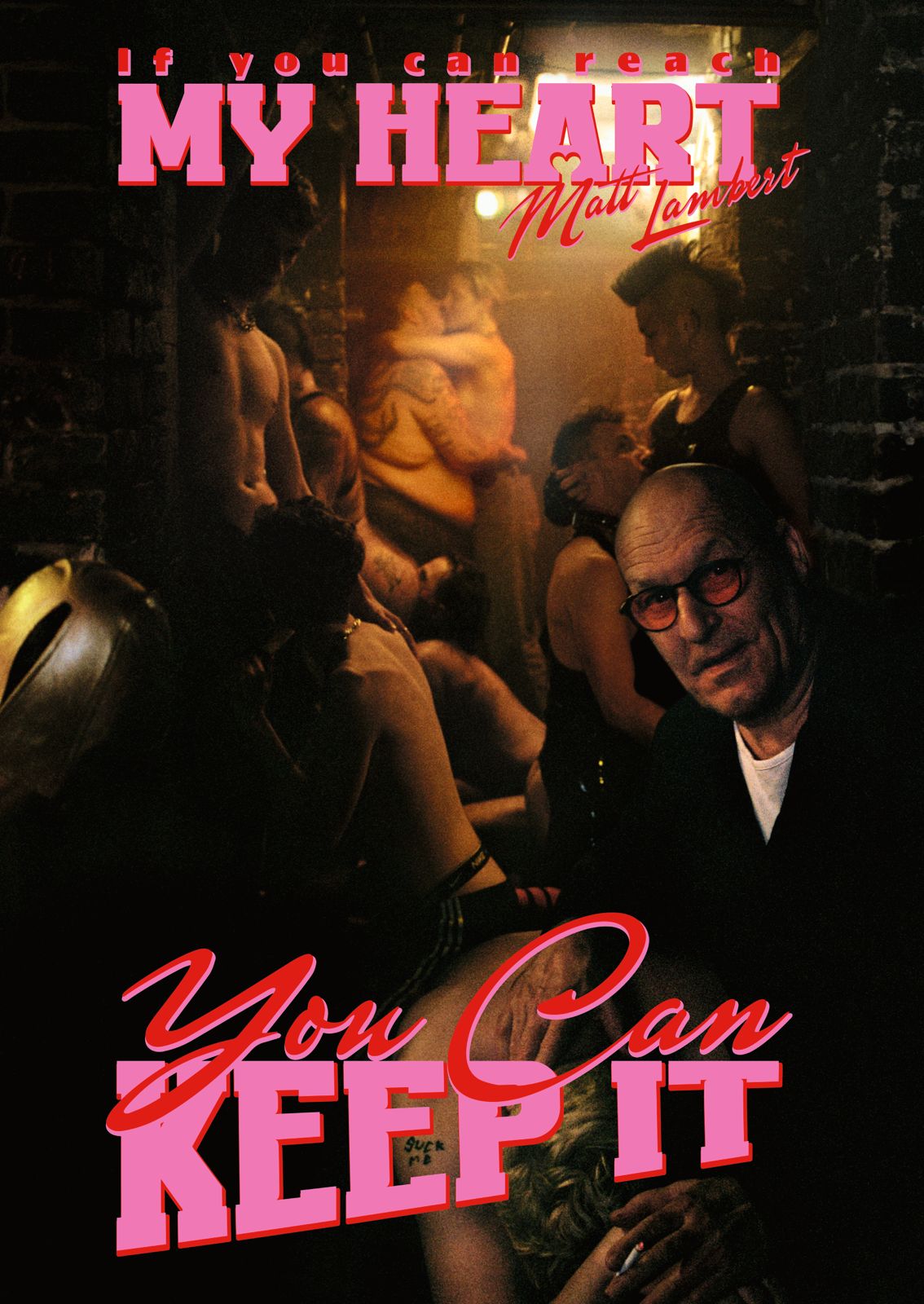

Matt Lambert Brings Wolfgang Tillmans Inside His Naughty Underworld

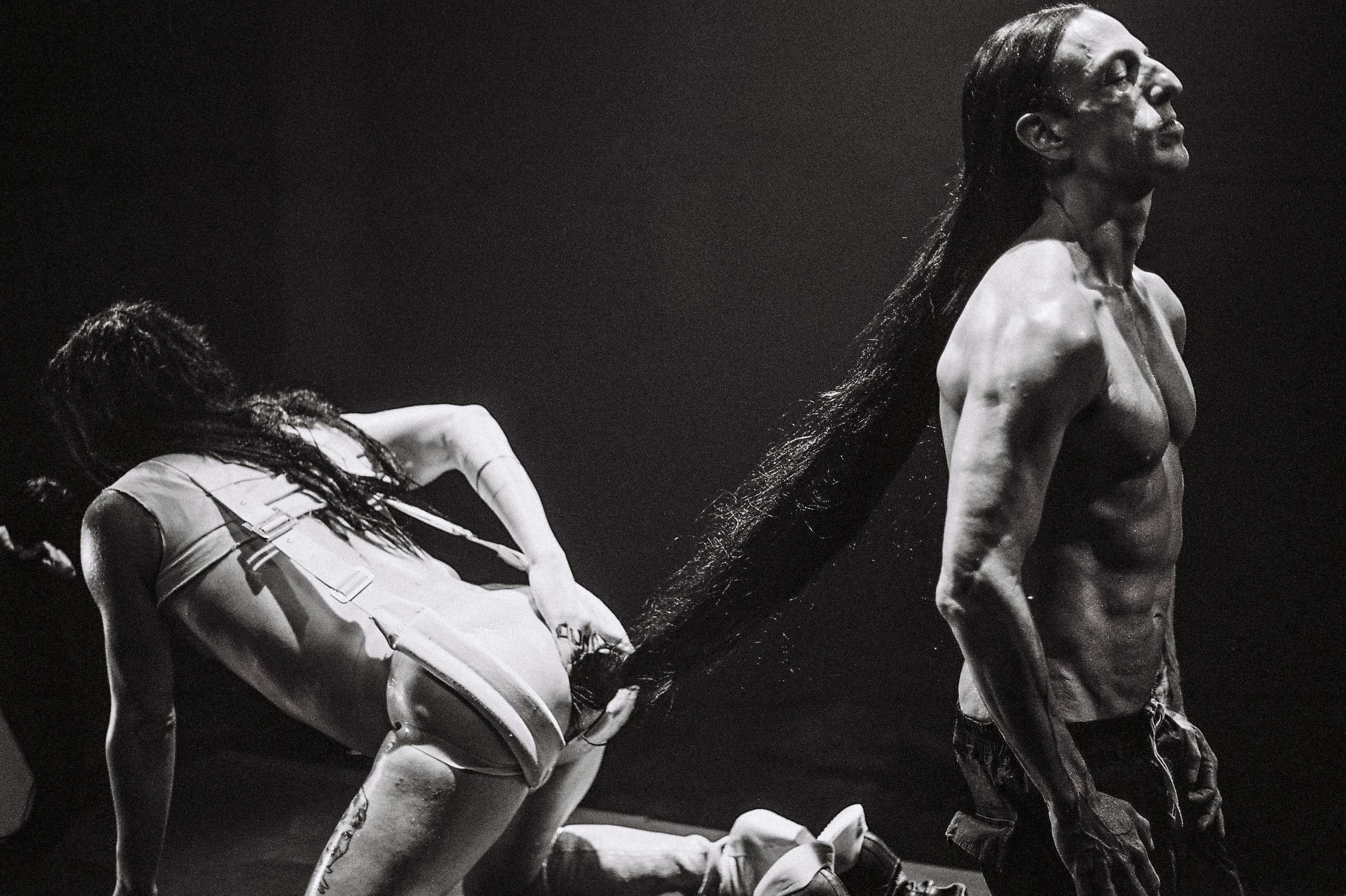

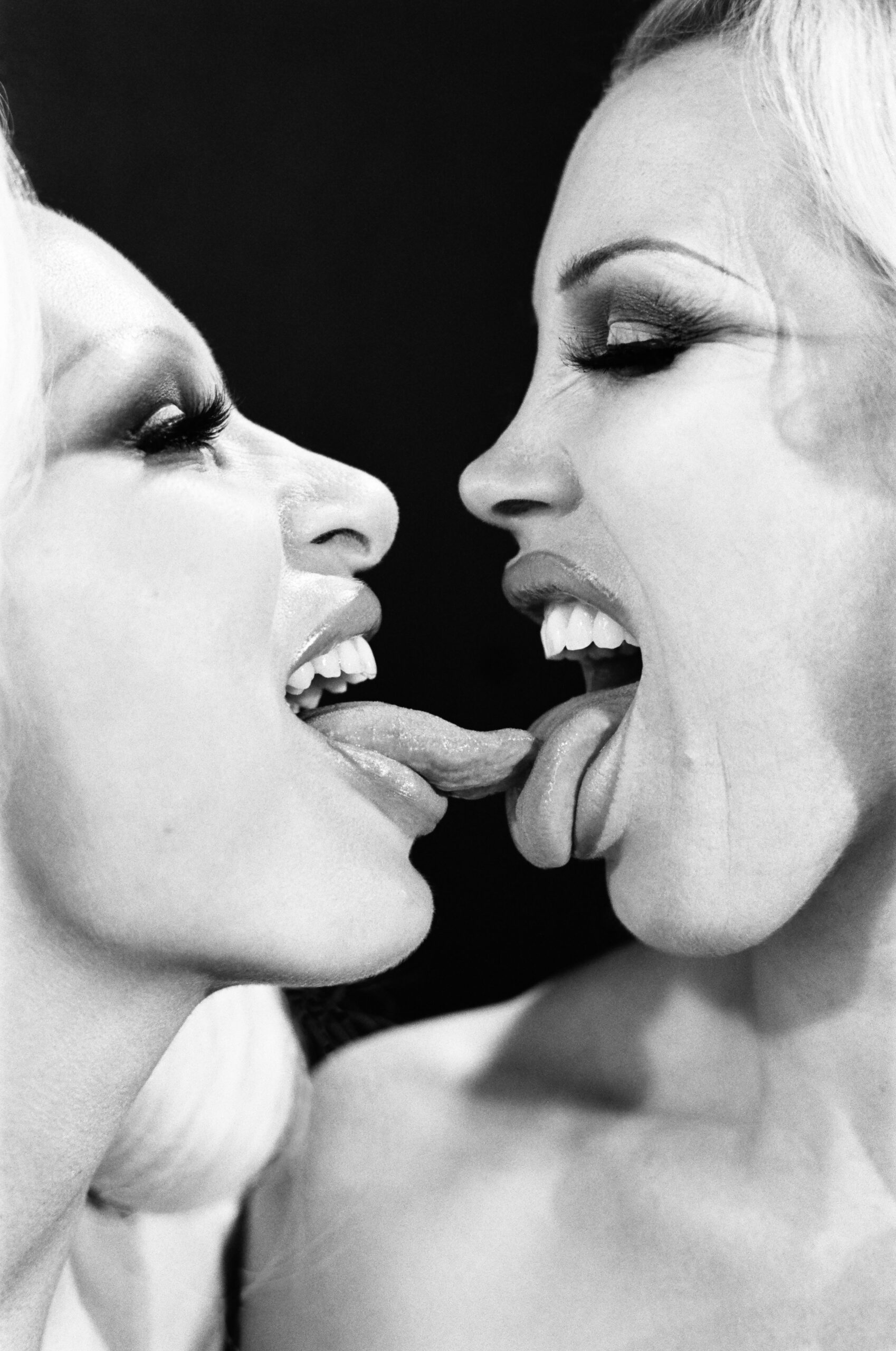

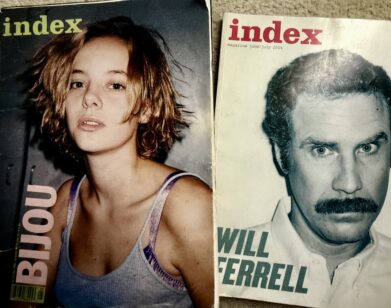

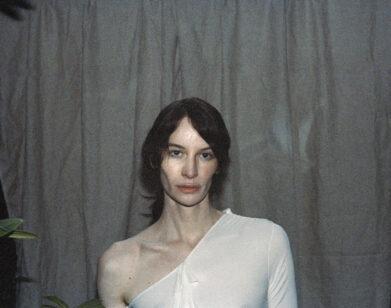

Matt Lambert has never been one to sit still. Over the past decade, the Berlin-based filmmaker and photographer has toggled between mediums with ease, directing music videos, curating nightlife, staging performance works, and producing films that blur the boundaries between sex, theater, and art. His new book, If You Can Reach My Heart, You Can Keep It, out with Baron Books this month, compiles film stills, portraits, sketches, and club ephemera into a tactile and dynamic portrait of queer life, arriving as something of an archive. “It’s not necessarily about how the work’s going to be received tomorrow, but it’s about what would make an art student or researcher pick one random thing off a shelf in the future,” he explained to his old friend Wolfgang Tillmans last month. To mark the book’s release, the two touched on everything from Vaginal Davis’ epic MoMA retrospective and Berlin nightlife to the urgency of preserving histories before they vanish.

———

WOLFGFANG TILLMANS: Hey.

MATT LAMBERT: Hi, darling. How are you? What are you doing? You’re coming back from Paris?

TILLMANS: It is the last day of the exhibition, and it closes on Monday. Next week they’ve booked three talks. There’s always a public talks program, and we squeezed three of them into the last week.

LAMBERT: Right, so you’re just going back and forth and getting the talk quota together.

TILLMANS: Yes, yes.

LAMBERT: You’ve been busy.

TILLMANS: Yes. It was a marathon of a project to put together in the first place, like the architecture and getting the whole thing to work. Then it was only six months to put all the actual work together, because everything was so much about the design.

LAMBERT: Yeah, of course. It was nice seeing that and seeing the Vaginal Davis show around the same time. For me, the most interesting stuff comes from artists that I know as human beings, obviously. Just to see these collections of work where the medium is still quite present. It becomes like, the archive of a life lived, the archive of curiosity, the archive of just the way that someone looks at the world. I think this is just so much more interesting to me. I guess that’s part of maturity as well, being interested in an artist for their worldview versus their aesthetic view. [Laughs] I think that shift happens when you get closer to middle age.

TILLMANS: This book feels already like a classic, capturing queer desire in the 21st century. It’s so much in the now. Yet you always seem to be, or you increasingly seem to be, informed by history and interested in queer history.

LAMBERT: Yeah. I was thinking about the first time that I looked at what I would consider—it is all relative—but radical queer work. I think there was always something more provocative and sexy about looking at work from a previous generation than what our current peers are doing. I guess for me, it was discovering things like Bruce LaBruce and John Waters. And then looking deeper and discovering Vaginal Davis and Queercore movements. I think all the radical queers and faggots I’ve admired have always been really in dialogue with history, too.

TILLMANS: True.

LAMBERT: At some point, as a filmmaker, but then also through these little nights at Sissy Smut, I started to realize part of my role as a filmmaker is also as curator of culture; of stories, of people, of characters. Then I started to realize, “Who’s telling the story of fucking David Hoyle to the kids? Who’s telling the story of Christeene [Vale]? Who’s telling these stories?” Maybe it was almost like a selfish curiosity at first, which has now become something that feels like an obligation. I have to preserve and I have to share these points of view.

TILLMANS: There is an eco-activist saying that goes, “We do not inherit the Earth from our ancestors; we borrow it from our children.”

LAMBERT: Yeah.

TILLMANS: I feel like we have the privilege to experience our slice of queer life, but we’re really handing it over and preserving it for the next generation—our sisters and brothers. I love how the radical queer core world is not only lateral but a vertical time, a layered heap of time. And we are connected through decades.

LAMBERT: I mean, look at someone like Bleach, right? For me, this is the modern incarnation of whatever that force is in a city like Berlin. This is someone who’s wildly looking into the future, but also wildly engaged with the past. It’s almost like that quote, “Time is a queer thing,” in the ways we engage with time and how we evolve. One day, I feel like 60, and another I feel 16. It’s a non-linear journey that we’re on. Also, looking back at stuff from 20 years ago that I absorbed, I’m like, “Oh.” To reinvestigate the things that inspired you, and to realize I had no idea what I was doing… With Michèle [Lamy], when I first met her, I just went on instinct. Then you sort of retroactively look back at those projects and see your growth and how you also related to those people.

TILLMANS: And you may unwittingly, unknowingly, create a masterpiece.

LAMBERT: Well, I’m a captain and a conduit at some point. But fucking hell, Christeene, Rick [Owens], Michèle, Charlie Le Mindu, Mark Saputo… I’m just creating a play space for all these energies to come together. The product is exciting for me, but in those moments it’s more about, “How do we create the most magical clashing of energies,” you know?

TILLMANS: You seem to have developed a really strong visual style without necessarily being behind the camera. How would you describe it? Because I see it very much between analog and digital. It’s clearly not retro, but it feels contemporary and it’s super textured. For example, the use of a heat infrared camera to record the extra heat of body parts having been in other bodies: High-tech, low-tech.

LAMBERT: In a way, it’s similar to the queer cultural timing thing. Intuitively, I always have one foot in the past and the future. That sounds really fucking cheesy, but in terms of an aesthetic, it’s always trying to touch a piece of that language from the past and keep it as an homage. For example, there’s this VHS film that I co-directed with my friend Julie [Chance], Release Me. It was this kind of lesbian summer anthem. I think our idea was, “Where are those lost tapes of things from the ‘90s in Berlin that people lament about?” You will start to find some, but where is that version that we want to see? It’s almost like we manufactured a faux documentation of a scene that was scripted. That sense of curiosity and discovery is something that I always hold onto in my work, even if I’m building it. It’s not necessarily about how the work’s going to be received tomorrow, but it’s about what would make an art student or researcher pick one random thing off a shelf in the future

TILLMANS: Yes.

LAMBERT: Some of the most magical research moments I’ve had in my life have been just pulling something completely obscure and random off a shelf. So I also start to think about, if everything we’ve made is not burned in 30 years, how will people engage with the work 30 years from now? It’s almost like looking at the work as part of history as I make it, if that makes sense.

TILLMANS: But I find you’re always moving forward. You’re always so full of energy.

LAMBERT: You too, darling. I mean, come on. [Laughs]

TILLMANS: [Laughs] But maybe that’s a level where it clicked between us when we first met, that there is a sense of, “Okay, he’s partying, but at the same time there’s a lot going on in the daytime.”

LAMBERT: I think we’re both just really fucking curious people. It’s this curiosity to dig and experience with someone, but then also to be able to preserve that for others. There’s a whole process in between, but that feels like something that we’re both drawn to.

TILLMANS: And David Hoyle, for that matter. I feel he’s one of the greatest poets and philosophers of our time, in a way.

LAMBERT: Well, when I did my very first Sissy Smut, I didn’t even know if that series was going to continue. We started with David Hoyle because I was just like, “For fuck’s sake, people just need to spend an hour in the room with David Hoyle.” I remember the first time I did, and it almost rewired me a little bit.

TILLMANS: Yes. It’s a reality check that many people would need.

LAMBERT: And things that I’ve heard from David, like 5 or 10 years ago. Now I’m like, “Oh, fuck. David saw. David knew.” I think we need to listen to our prophets a little bit more closely sometimes too.

TILLMANS: Yeah. And you’re refreshingly unfazed by distinctions between art and commerce, or porn, or theater.

LAMBERT: Yeah. It’s a reality, but it’s an identity crisis at times too. You know what I mean? Because especially in Germany, people really want to put you in a category when you bounce between all these different spaces.

TILLMANS: I think it’s an international phenomenon, people trying to box you in.

LAMBERT: Yeah. I mean, I started in animation, and then I went into photography as a way just to explore people, explore energy, explore intimacy. Then I brought all that back into the filmmaking work. Photography has always been a tool, but it’s more like a tool that leads towards something else. It started as a sketchbook, and then people were interested in it, so I started publishing that work. But for this book, there’s a lot of film stills and stuff on stage and little sketches and photos and I hope people can see the link between it. I think it’s been confusing for some people as to how it all fits. This book made it all make sense for me a lot more too, hopefully.

TILLMANS: I find it super attractive in the way that there’s a lot of space devoted to skin and abstraction, and abstraction of skin. But what’s really striking to me is that a lot of your work is about real places. A lot of designers in this day and age have moved online, and it feels a bit lonely. You always seem to gravitate also to the real places and spaces that still exist.

LAMBERT: Yeah. I did a lot with digital space, but I think the most interesting review I got was when I started dabbling in art film, but in a porn space. Someone said about this film Flower, “This film does not want to make me masturbate. This film makes me want to go out and have sex just like that.” [Laughs] So it’s almost this thing of reminding ourselves that we’re still all of this kind of abstraction. We’re still working toward tangible human connection, in theory.

TILLMANS: I love that. And the trans encounter that has not been secured and negotiated with dick pics and stats.

LAMBERT: Yeah. That also felt like an interesting time to work on this period too, the last 10 years. Because the ways in which we enact and talk and fuck has changed so much. So maybe this is an archive of the last era of finding intimacy in public spaces, or finding intimacy spontaneous. I hope not. But it’s also presenting ideas of the world that maybe don’t totally exist, but should.

TILLMANS: Yes.

LAMBERT: Encouraging aspirational eroticism.

TILLMANS: What drives me also is photographing queer spaces, or general spaces that don’t actually have to be queer. It means photographing spaces where people can be free in their bodies as a testimony for the future that this existed. This happened, so it can happen. It should happen. And it shouldn’t be forgotten and undone.

LAMBERT: I’ve been writing this movie set in 1932 for the last few years, and you start to realize that so much of our history as queer people, but as people living in Berlin, is completely erased, right?

TILLMANS: And how is that going?

LAMBERT: When I worked on this film El Dorado a few years ago, it was a wonderful experience to open up my interest in the era. It’s the underground of the queer Weimar era in Berlin, a moment in time where things are all falling apart, but also looking at how communities that have been perceived as “other” their whole lives. Communities that have been on the fringe, that have never really been seen by the systems and the governments that are now coming for them even more. These are people who have been resilient their whole lives. So it’s looking at how communities grow tighter when things start falling apart, how queer people use humor and sex and other tools of survival to create in these moments of craziness. That project has kind of been something that realizes that so much of this history has been erased, and so much of the history that’s been told was the history of the famous cis white ones, the famous cis white lavender marriages, you know? So, after speaking with historians, everyone was really excited about the idea of fiction, because it allows us to touch an impression of the essence of it all through a feeling that maybe exists now, but knowing that we can never, ever truly know. But again, with this idea of time being this nonlinear thing, potentially we can access the same energies of what it felt like to be walking through a cruising space in Tiergarten in 1932 and what it felt like to be moving through a backstage or a dark room. It’s almost like imagined realities are the theme.

TILLMANS: And that is a film you’re producing now?

LAMBERT: It’s a film I’ve finished the script for. We are in development and finance stages, and it’s something that I hope we can get made. The hard part was doing the script, working with historical consultants and a writing partner and getting years of stuff together into the story that just feels kind of easy and accessible and moves in a modern way that people living in Berlin now, or people that are young now and queer in the world, can understand and see the connection to this era and how it inspired and influenced our aesthetics and the way that we have sex. All of that was born in this little pocket of Weimar in Berlin in this moment in time.

TILLMANS: I mean, your work’s been breaking ground the last 15, 20 years, and the book shows it all. I hope that this film you’re working on can bring it to a broader audience.

LAMBERT: I hope so. Let’s put this in big, bold quotes: “Looking for money? The book is the prologue. Help us fund the movie.”

TILLMANS: It was fantastic talking to you on a Sunday morning, Matt.

LAMBERT: Oh, you too, darling. Thank you so much for this.