XXX

“What a Ride I’ve Had”: Peter Berlin on Sadness, Immortality, and Good Sex

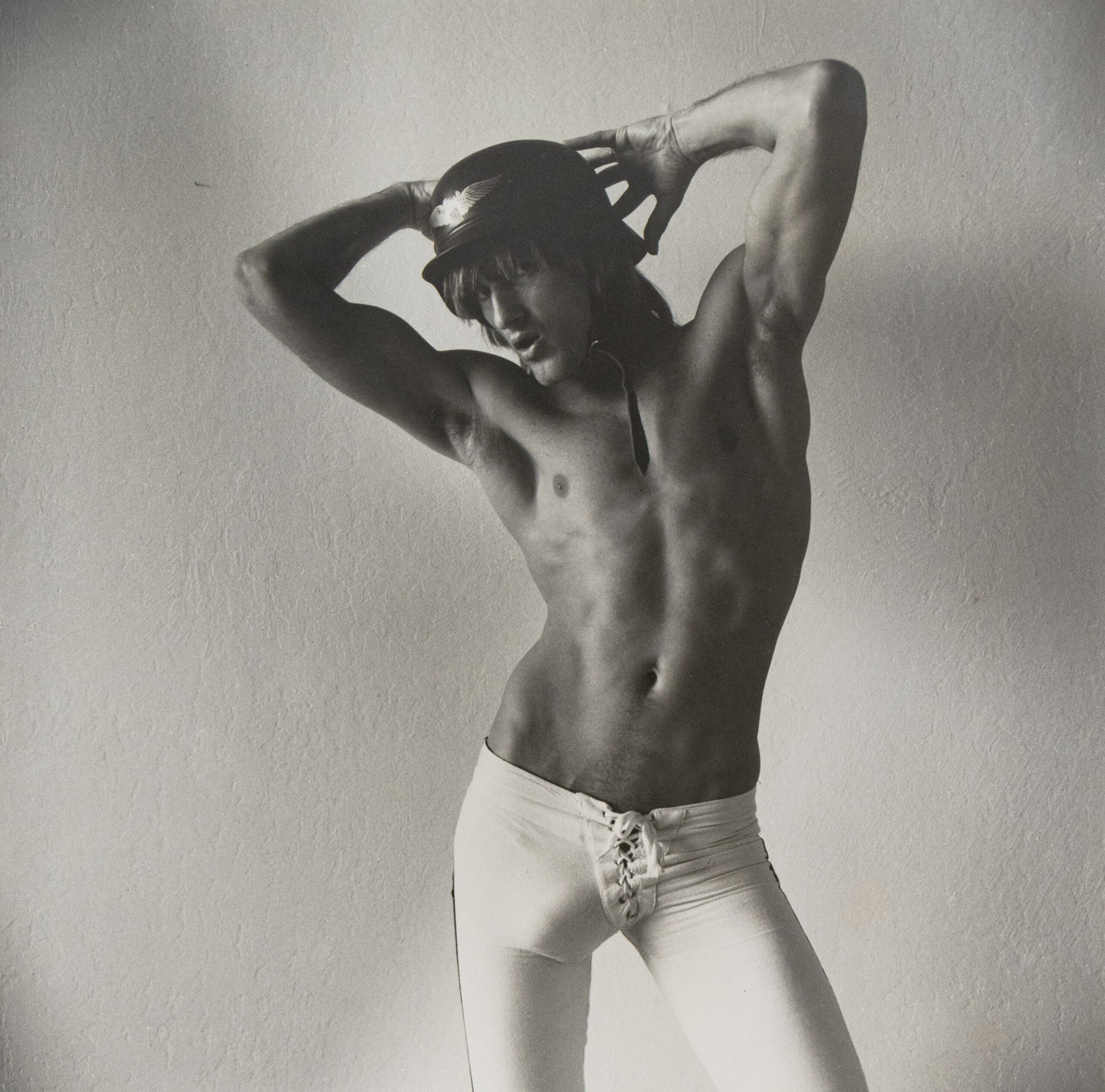

Self Portrait in Helmet and White Football Pants, c. 1970s . Signed in black ink, l.r. Vintage gelatin silver print. 14 x 11 inches, sheet. 10.25 x 10.25 inches, image.

“There was a camera behind the mirror,” explains Peter Berlin when I asked him how he oriented himself in his now immortal self-portraits. The statement seems prophetic and fitting, in that the entire arc of the Peter Berlin persona hinges on the notion of deep self-reflection, proving, maybe triumphantly, that narcissism can in fact be a good thing. Born Armin Hagen Freiherr von Hoyningen-Huene in 1942 in Poland, Berlin begin his career in the 60s as a celebrity photojournalist in Germany, where he learned what he calls “the distance between the person and the star,” as he says in The Peter Berlin Collection, a new catalogue by the historian and book dealer Gerard Koskovich. After years of globe-trotting—spending time in Paris, Rome, and New York City, where he met and forged friendships with other queer erotic icons like Mapplethorpe and Tom of Finland—Berlin finally settled in San Francisco in the 70’s. This was where he truly became Peter Berlin, haunting the bathhouses and bars where gay men, for the first time, were taking up space. It was here that he began to document his “photosexual awakening,” on full display in Peter Berlin: Permission to Stare, his very first L.A. retrospective currently on view at Mariposa Gallery. “The Peter Berlin image is only there because I connected my dressing up and feeling horny with a camera and froze it in time,” the artist told me last week when we talked about sadness, immortality, and what the fuck it means to self-identify as an “artist.”

———

PETER BERLIN: Brontez is such an unusual name. It’s great.

BRONTEZ PURNELL: Oh, thank you. Well, my first name is Justin, but my mom gave me this name so people would remember me.

BERLIN: Oh, yeah. I have this girlfriend in Canada and she checked on you when I talked about you, and she said, “Oh my god, he’s such a good writer.”

PURNELL: Oh, that’s so sweet.

BERLIN: You see we have a certain way we think of ourselves, and there are people who are feeling completely comfortable, feeling good about themselves and say, “Yeah, I know I’m a good writer. You don’t have to tell me.”

PURNELL: Oh, I wish I felt that way, but I question myself a lot. But I think a good writer should.

BERLIN: I’ve questioned myself all my life, and it is interesting how people perceive you and how you perceive yourself.

PURNELL: Oh, always. Well, I want to start asking about this show. It’s really beautiful and evocative and I want to ask, what do you think sets this apart from all the other gallery shows you’ve done?

BERLIN: I don’t see any difference. I never enjoyed exhibitions and this whole idea of people reaching out to you in person because I’m not there in person, because I don’t like the idea of meeting people. The creator would ask me, “How do you like people?” I say, “I don’t like them.”

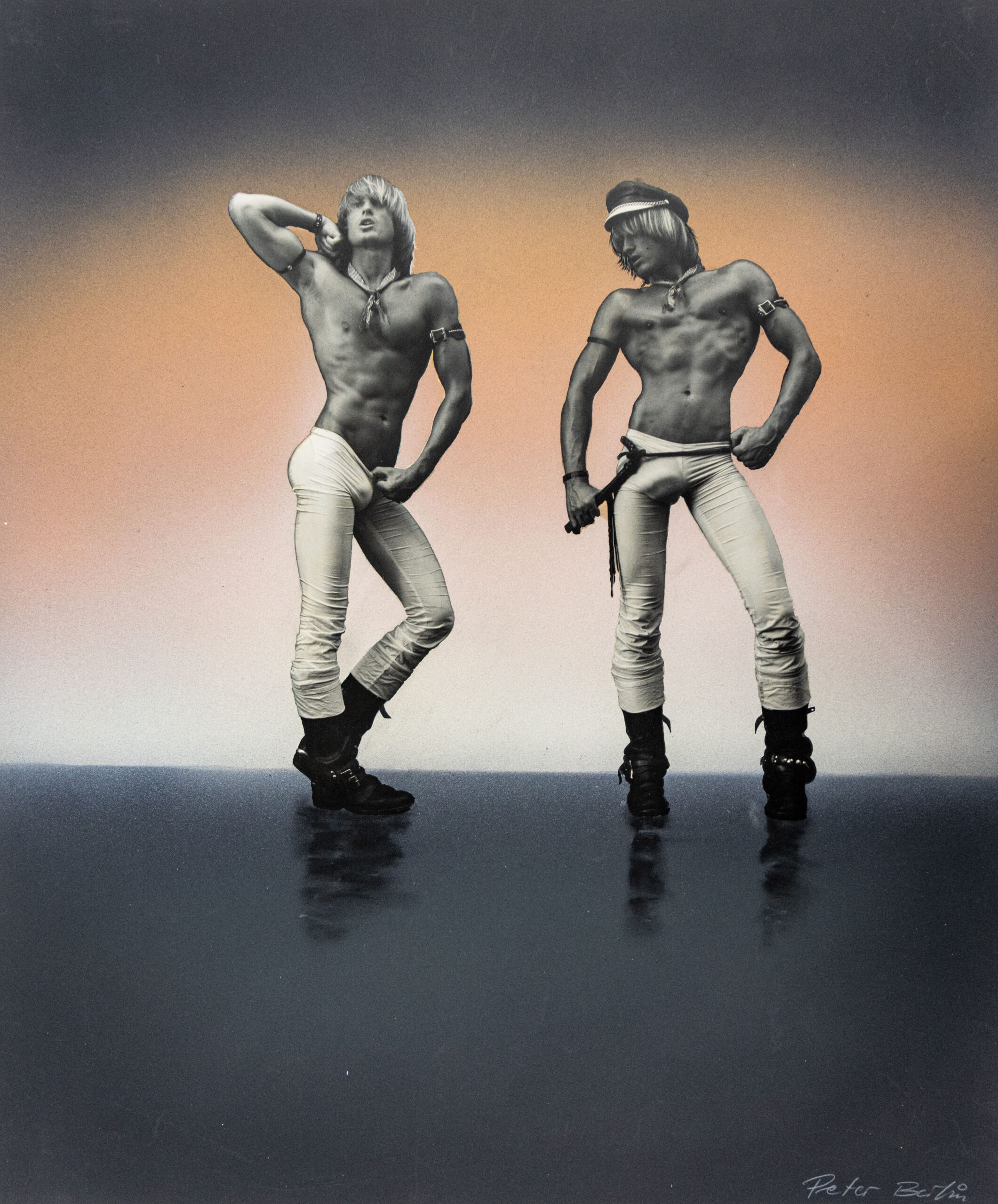

Double Self Portrait with Glowing Pink Background, c. 1970s. Signed l.r. Vintage hand-painted gelatin silver print. 24 x 20 inches, sheet. 23 x 19 inches, image.

PURNELL: I completely understand.

BERLIN: Oh, good for you. I mentioned to the curator of the show, that actor [Russell Tovey], what’s his name? I don’t know now. He asked me, “How do you feel?” And I said, “If the exhibition was what I think is happening now, it will happen. And if it wasn’t happening, I would feel the same.” So I’m not excited about the show or any show now.

PURNELL: Do you think that’s related to the idea that your body and the consumption of your image has always been the art? I think for any artist, that gets tiring at some point.

BERLIN: You see, I don’t even see the difference between a regular person and an artist. I never thought of myself as an artist. The title “artist” is something humans have come up with, and I can’t go there. I don’t see the difference between my mother, who wouldn’t be called an artist, but I am? Do you follow my thinking?

PURNELL: Yeah, I do follow that.

BERLIN: These are the boxes we created for ourselves. “You are an artist and you are not.” And now you see, I’m even a certified legend—

PURNELL: Yes, you are.

BERLIN: I can see that I’m talked about and there’s something about that image, and that is all nice and dandy, but who is then considered a legend or not? Anyway, all these titles! I am a more simple person, and to see us all running around on the planet, we are actually doing more harm than good.

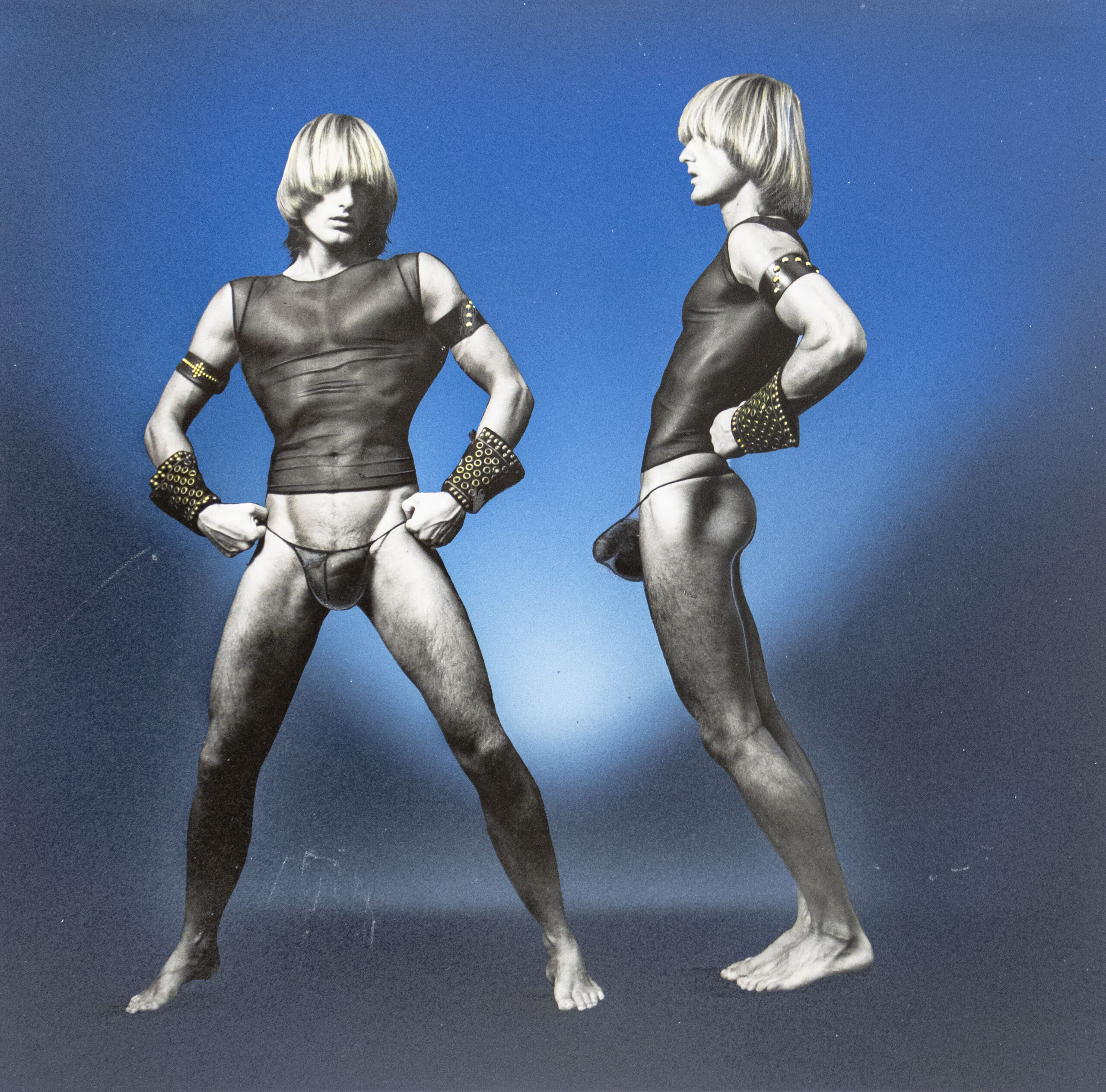

Double Self Portrait II, c. 1970s. Signed in pencil, l.r. Vintage hand-painted gelatin silver print. 10.5 x 10.5 inches, image. 14 x 11 inches, sheet.

PURNELL: True. Well, I guess what I would ask is if you have a problem with the term “artist,” what compelled you to take pictures of yourself and share that process with the world? Because certainly not everyone does that.

BERLIN: The reason I did the pictures is because there were cameras around. I’m a very visual person. I looked in the mirror, I said, “Oh, I like what I see.” But the photos I was taking at that time were never because I wanted to show them to anybody or even show them in a gallery. That all happened because I was living in this world where these things exist. So for me, it was a private thing because I thought, “Oh, that’s nice. I can freeze that image of what I liked.” But then I became Peter Berlin, and I made my films and I was offered to show my photographs, which I found very nice and exciting. “Oh, people want to see my photographs.” But the intent was never there. You see, when I compare myself to [Robert] Mapplethorpe, who really did his photographs with the intent of being famous and rich, or when you want to be a movie star or a prima ballerina—that is a direction where people go with sometimes a lot of energy and dedication. But I didn’t have that. I never knew what I wanted to do in life, other than I did the pictures and I wanted to look sexy. So I did my clothes and all that became something where I am more surprised even now that after 50,000 years there’s still an exhibition in Los Angeles. You see, what is urgent to me is global warming. I say, “People, wake up!” The world doesn’t really need an exhibition of Peter Berlin’s photographs. People should concentrate on changing their lifestyle. I feel I’m part of the problem of a human being running around on this planet and doing harm. You see, I’m very much consumed by our activity. We are still living our lives like 50 years ago. But things have changed, and it changed to something where I can’t even put my head around what is happening with the world. In America, with the political drama, that is more what I’m thinking about rather than my exhibition in Los Angeles. You see, I am sort of puzzled a little bit that I didn’t lift my finger for 40 years. I didn’t do anything anymore to further my career. I never saw my thing as Peter Berlin as a career. It just happened. And I know now it has to do with sex, sexuality, and that’s what people like. If I would have photographed flowers, I might not have been in the headlines anymore.

PURNELL: Do you remember your first exhibition?

BERLIN: Yeah, that was very easy to remember because I have a very bad memory, but I was living in Berlin and there was Volker Janssen, who had a very beautiful gallery in mid-Berlin, and I think he must have seen my photographs. And he said, “Oh, you should show that.” And I said, “Yeah, if you think so, do it.” You see, it was coming from the outside. I never reached out to people. I never ran around with my photograph and a big map and ran around showing it to galleries. The gallery came to me, and then it snowballed when I came to America and I met someone who had a camera. I said, “Oh my God.” Like a movie camera, an Arriflex. I said, “Okay, let’s make a film.” So that was what really put me on the map, because I was then very visible and of course running around as Peter Berlin. I got a lot of attention and that was exciting. But immediately I realized the downside with being recognized and being looked at as something, what they thought I am, because I didn’t meet anybody who really saw me as who I was. The beautiful creation of that image created all kinds of things and people. But I realized that people were always surprised, “Oh my god, you are not as dumb as I thought.” Because that’s the first thing that people think, especially when a girl is young and blonde and pretty. “There must be something wrong with that person.” And I was that dumb blonde running around as a man, and then people said, “Oh my god, you are so different than what I thought.” I said, “Now, whose fault is that? Is it mine or yours?”

Self Portrait Flexing Bicep, c. 1970s. Signed, l.r. Vintage hand-painted gelatin silver print. 24 x 20 inches, sheet. 23 x 19 inches, image.

PURNELL: Well, I want to ask you a logistical question. It seems like when you’re taking a self-portrait with a camera, it’s not like now, where you just sit your phone down. You have to focus, you have to find the right light, you have to do all this extra stuff. How were you able to take these very pristine and precise photos?

BERLIN: Actually, it’s really not that pristine compared to a photograph of Mapplethorpe, which I would call pristine and perfect. Now, I was benefiting from the ability of a camera. You just put a camera on a tripod and there is light coming in from the window and then you click the button and there is the picture. You see, that’s different than sitting down and making a painting of me, where I sit for two weeks to make an image. The camera was doing the work and I benefited from whoever invented the camera to use it to freeze my image. And the pristine thing is, the camera is really well-built and gives you a pristine photograph. I think that is the talent of a photographer being more or less an editor zooming into something. And I zoomed into me and there it was. I was tickled and surprised and delighted when I saw a photograph, which I was carefully preparing by having a mirror behind the camera so I could see what I was doing. And then I took thousands of images over time, and I am glad that I did that. And then the whole thing of the fame of Peter Berlin, it’s something that was working by itself and not so much by me forcing something. It was the world around me using my image in the world, what they call the “art world.” Because when I started to do my photographs, photos were not considered art. And that’s why I mentioned when people talk about art, when they say what it is or what it isn’t. So after Mapplethorpe, suddenly photographs were lifted up in the world of art and fine art and this art and that art. So I can’t take myself too seriously and I can’t take too much of everything else seriously. What I then realized was that the world of art was very much connected with commerce, with buying and selling. And that includes the fashion industry and the music industry. If Taylor Swift would have been born a hundred years ago, she would maybe sing her song and people would have liked it, but then look at what happened over a hundred years—that suddenly it’s transposed and transformed into money. You see? And that is where I have my reservations. When there’s a band in the subway playing, nobody pays attention. But now if somebody plays a song by, I don’t know, Coldplay or the Beatles, suddenly there is an awe. And that is interesting, the psychology of people.

Double Self Portrait with High Top Converse, c. 1970s. Signed, l.r.. Vintage hand-painted bgelatin silver print. 24 x 20 inches, sheet. 23 x 19 inches, image.

PURNELL: I think that you said something so beautiful about there being a mirror behind the camera. That just feels so poetic to me.

BERLIN: Yeah, because you see the mirror in itself. I thought a lot about it. Can you picture yourself? The idea of having the reflection of the world behind you, I find that very, very interesting when you suddenly become the focus of that whole world. So when I looked in the mirror and I looked at myself and I liked what I saw, what I think is not normal—because I think there are many young people that look in the mirror and don’t like what they see—this was my focus, because I didn’t know anything was more interesting than my persona, my body, my mind. I’m constantly entertained by my thoughts and usually, I find myself more interesting than the people I’m dealing with. It is a fact that I’m easily bored. Now, when I was Peter Berlin, I was not going out to meet people to sit and chit-chat. I wanted to have something very, very focused. What people call “sex”—that was a focus as Peter Berlin, and that is now ancient. Now, I am the one who looks back and it entertains me to see, “Oh my god, that image is on the internet where people get to see my image as much as in the 70s in magazines and in the films.” And usually, guys had a good time with me where I was not present, only my image was used as a template for getting off. And I think, “Oh, that’s a good thing that I did, giving people a good climax.” That’s what I think the essence of good sex is. You have pleasure and you give pleasure.

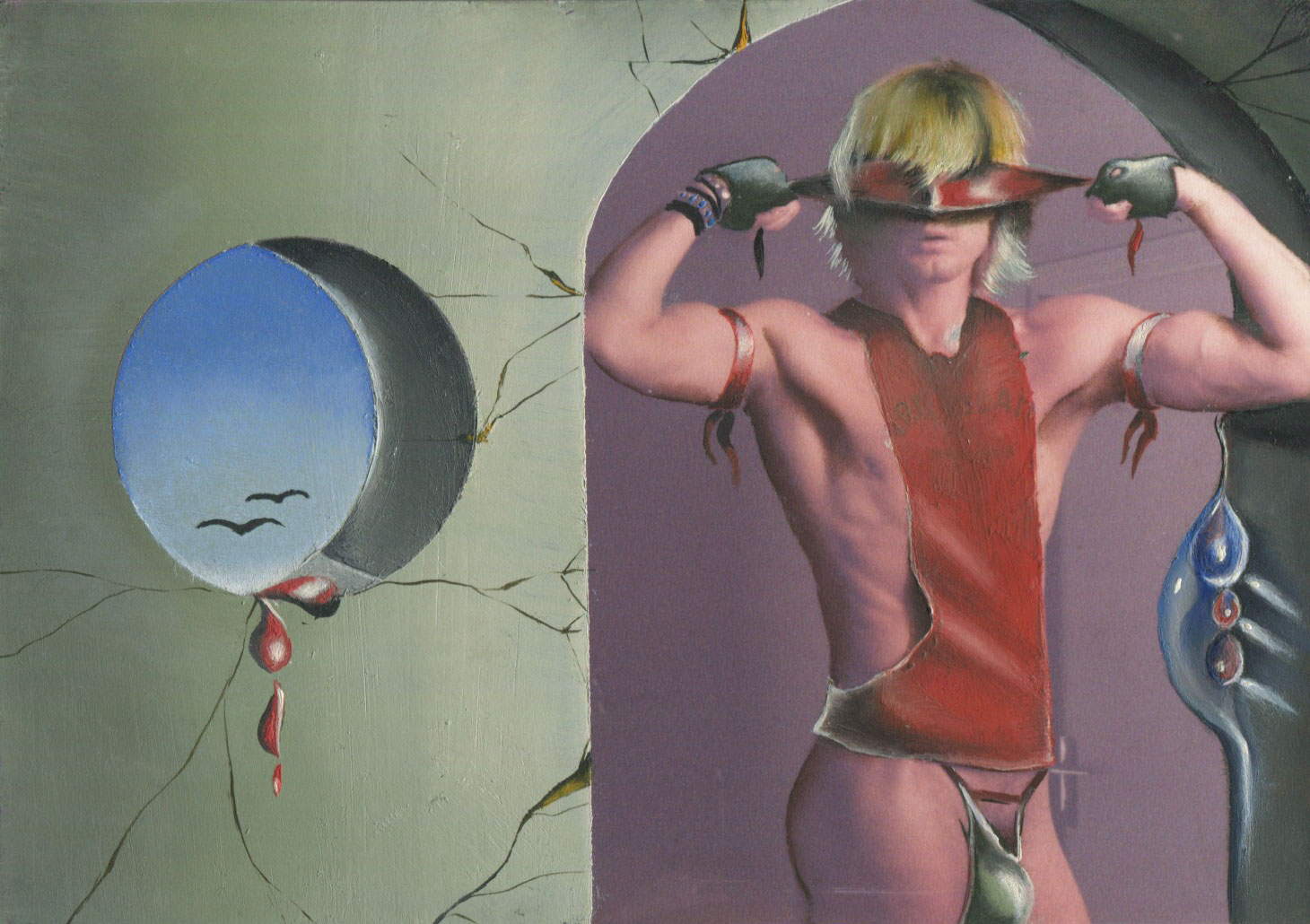

Self Portrait with Blindfold and Porthole, c. 1970s. Signed in black ink, verso. Vintage hand-painted C-print. 3.5 x 5 inches.

PURNELL: Do you think the image of Peter Berlin is immortal?

BERLIN: Not necessarily, because I think if we go the way we do, that means we will be killing ourselves and killing the planet. And when we are killed off, the satellites will all fall down and the images of Peter Berlin will not be there. And for that reason, I will not be immortal, like all of us. And that is why I said, “What did we do wrong, that we have ended up killing ourselves and killing the planet?” I mean, the planet will survive and the cockroaches will be there, but many of us will not be here one day. Myself and Jesus and Gandhi and Andy Warhol, we will all disappear. And that is unfortunate.

PURNELL: I understand.

BERLIN: Just to finish up, how are you doing? Are you not as frustrated as I am? I’m a very sad person, but I still have a sense of humor. I see so much sorrow and pain around me. So when people are still creative I say, “Okay, this is really nice and I am glad.” And that’s my favorite question when I meet people: “Are you content? Are you happy?” There are some people who are, and I’m glad for them.

PURNELL: Ever since I was a little boy I’ve basically been sad. But I think it’s interesting what you said, “I see the world reflected behind me.” I think that’s why I still feel the need to document my experience or at least just convey it, so that I don’t feel so crazy all the time. I’m like, “Does anyone else feel this way!?” But it’s nice to hear you talk because I completely agree with everything you say.

BERLIN: Thank you so much for still showing interest. I hope I maybe brightened up your day a little bit with my babbling and I wish I could be so much more happy, but that is not in my life. I never really was this very happy person, but my god, I’m so grateful for my life. What a ride I’ve had.

PURNELL: I love you with all my heart and I will talk to you soon.

BERLIN: Thank you so much Brontez. Until next time, maybe.

PURNELL: There will definitely be a next time.