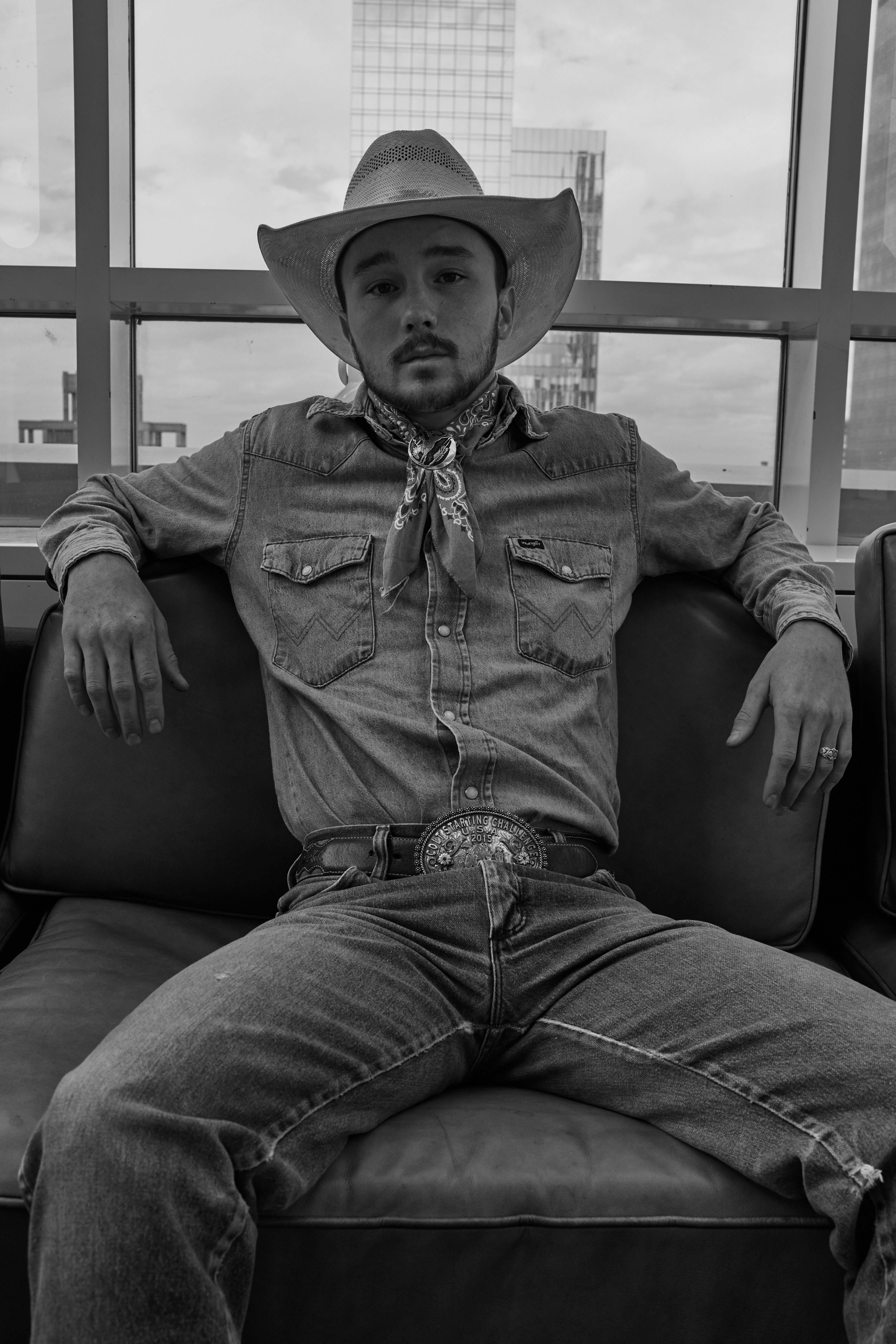

The heart-stopping cowboy film that won over Cannes

The Marlboro Man and John Wayne. Ten gallon hats and Spaghetti Western whistles. East of the Mississippi, the word “cowboy” has come to evoke—in equal parts—its gunslinging stereotype and the urban American myth of a life pastoral: one brimming with rustic authenticity and transcendent natural solitude. In South Dakota, cowboys learn to ride before they learn to crawl. Brady Jandreau, in fact, was just 15 days old when he sat atop his first horse. Granted, his parents may have been holding him, and his mount may have been exceedingly tame and long in the tooth, but the newborn was well on his way to mastering a bucking bronco.

By age three, he was competing in kids’ events, riding sheep solo in nothing but a t-shirt and diaper, and by 12 had graduated to training full-sized horses to be mounted for the first time. Most babies grow up in strollers, cradling a stuffed animal; Jandreau grew up on horseback, holding the reins.

Listening to him speak with his soft, Midwestern lilt, however, it becomes clear that life on the range is not so much a romantic novelty as it is a grounded existence that involves a lot of hard work. Horse training is no easy hobby, but instead a job that requires immense amounts of effort: a science and art, and Jandreau is a natural prodigy.

At 20 years old, the cowboy suffered a near-fatal injury that put his professional dreams on hold. When competing in saddle bronc-riding (an event in which the horse tries to buck off its rider) at a rodeo in Fargo, North Dakota, one of his feet got caught in its stirrup, and his horse stepped on his head. Jandreau woke up five days later with a plate in his skull and doctor’s orders not to lift over 10 pounds or even jog for six months, let alone do the one thing he had grown up doing: riding. His injury was practically a death sentence.

Like an avalanche seen from afar, the video of the incident is only a few seconds long and remarkably quiet: disasters, after all, rarely telegraph their destruction. Jandreau has seen it hundreds of times, and the actual clip can now also be found in the new film from director Chloé Zhao, The Rider, which premiered in May at Cannes’ Directors’ Fortnight and took home the top prize—the Art Cinema Award. A loosely fictionalized version of his story, the film stars Jandreau, his family, and friends, and depicts his arduous recovery and coming to terms with his injury. Most of all, the film explores family life in America’s heartland and the cowboy ideal of “riding through the pain.”

Jandreau and Zhao met for the first time when the filmmaker visited the ranch on which Jandreau worked at the time. The two became fast friends—“we call her Aunty Chloe,” he says—and after he taught her to ride horses and move cattle, Zhao knew she had her star. It wasn’t until about a year later, however, when Jandreau had his injury, that she also had a story.

According to Jandreau, about 80 to 85 percent of the film that resulted is true to life. “I played a modified version of myself,” he explains after having seen the movie for about the 20th time, “so it wasn’t that weird, you know—kind of like seeing myself videotaped. But the more times I watched it the more times I could sense I truly was acting.” Even though he admits that reenacting his injury was difficult emotionally, he also says that there was some therapeutic value: “Being able to actually see it helped me accept it more.”

As for what he’s up to now—well, the doctors may not be too happy. He started riding horses again only about a month and a half after his injury, waking up every day at 5 A.M. to train, and shooting with Zhao from 1 P.M. to dark. Currently, he runs his own breeding program, Jandreau Performance Horses, alongside his wife and three-month-old daughter. As for whether he wants to act again: well, he would be willing, just so long as he could make filming work around his life on the range.

THE RIDER IS OUT IN THEATERS APRIL 2018.