TRUE GRIT

Luke Gilford Reimagines the American Cowboy

The specter of the swaggering, bull-riding cowboy holds a paradoxical position in the mindset of popular culture today. Once the image of masculine, suede chap-clad bravado and unflinching grit à la John Wayne, the cowboy has become a metaphor of sorts for an unyielding, decidedly American, individualism that chafes against convention. The rise of Lil Nas X and his 2019 camp-infused cowboy ode “Old Town Road” served as a poignant reminder that being a cowboy is as much an attitude as a way of life.

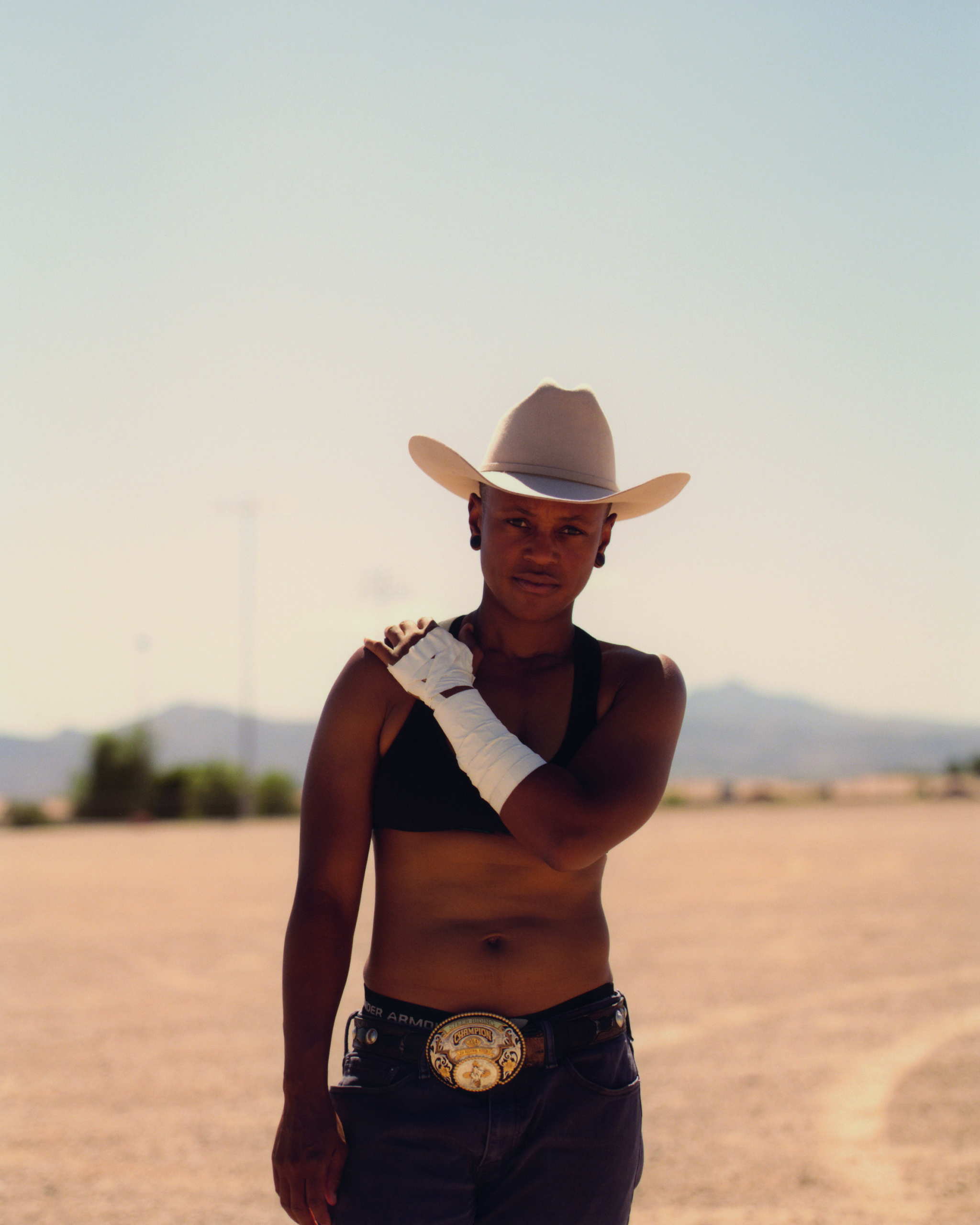

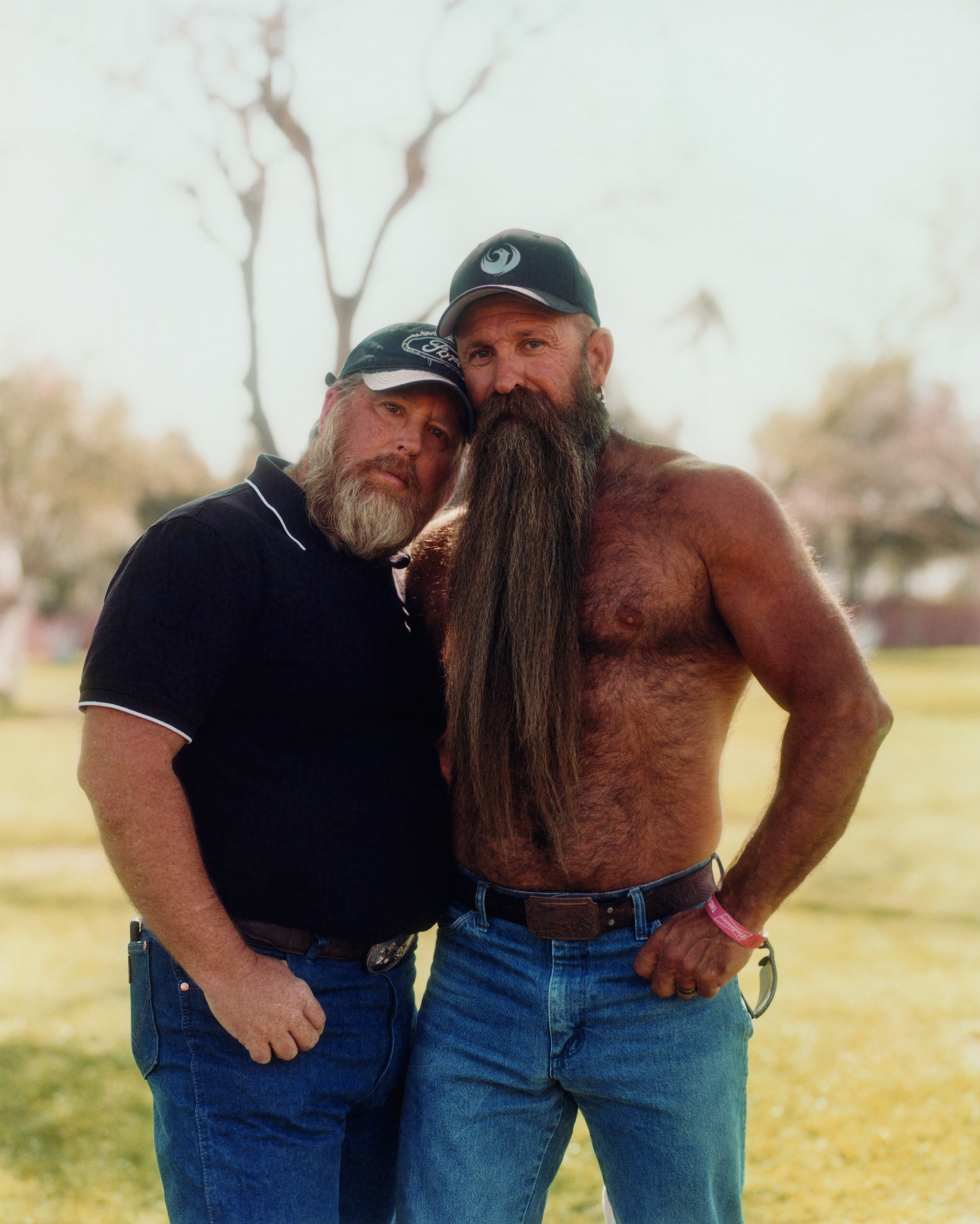

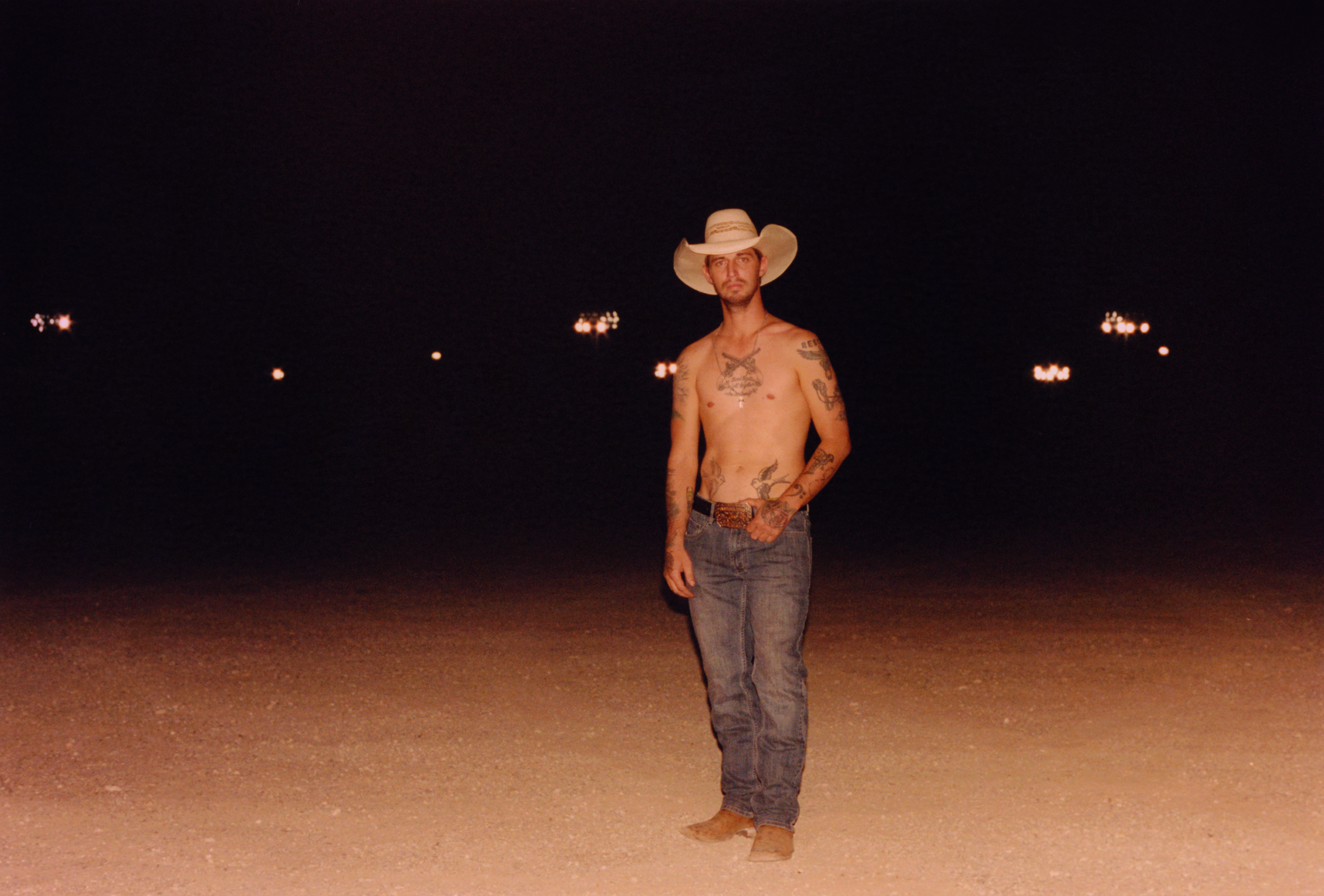

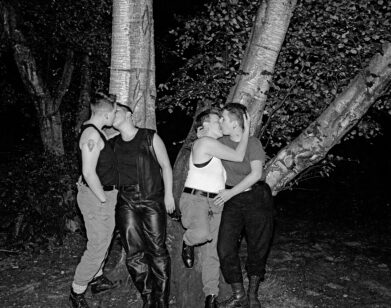

Now, with his book National Anthem, the photographer Luke Gilford offers a glimpse into the world of queer rodeo and the cowboys and cowgirls who comprise its tight-knit community. Shot over the course of four years across rural America, Gilford’s portraits call to mind Richard Avedon’s 1985 publication In the American West, a stark, unflinching ode to the American frontier and its grizzled inhabitants. Like Avedon, whose images challenged a long-held fantasy of the Wild West, Gilford depicts a community that embraces the cowboy lifestyle without sacrificing its queer identity.

At once a celebration of the world in which he grew up—Gilford’s father was a card-carrying member of the Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association—National Anthem is also a rejoinder to it, an unapologetically proud confrontation of a culture that has long clung to rigid archetypes of masculinity, race, and sexuality. Ultimately, as Gilford is himself quick to point out, National Anthem isn’t about undoing the myth of the American cowboy as much as recognizing that such a myth has more than one version to be told.

———

JOSEPH AKEL: National Anthem is a very personal project for you on several levels. Your father was in the Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association, correct? What was it like growing up around that?

LUKE GILFORD: You’re correct, my father was in the Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association, and so all of my earliest memories are from rodeos. The rodeo is a performance that certainly had an impact on my understanding of power and vulnerability, and it’s also very visual. I think that it really inspired me as a young kid. There’s people and animals and golden light, and there’s the peaks and valleys of pastel landscapes, bleached hair, red lipstick, leather, denim, dirt. I was really drawn to that spectacle before I even could understand the other layers of toxic masculinity and homophobia and Christianity that sort of permeate that culture. I really loved some aspects of Western culture, but then as I grew older, I had a very conflicted relationship with it. It was actually in San Francisco when I first saw a group of queer cowboys. And they weren’t like the Village People drag as cowboys—I know a real cowboy when I see one, having grown up in Colorado and traveling the Southwest with my rodeo parents. I talked to several of them that day. They really encouraged me to come to the next rodeo, which happened to be the following weekend in New Mexico. So the next weekend I was in New Mexico, at my first queer rodeo.

AKEL: What were your first interactions like with the rodeo community? I imagine it was not something where you could just jump right in with your camera and start photographing.

GILFORD: I took it very slowly. I became a participant and an observer. But the community very warmly welcomed me and knew my relationship to the rodeo. Slowly but surely, I made friends in that world. It was a pretty big juxtaposition from the urban queer culture that I’ve been living in for the last 10 years. Most people didn’t have smartphones, some don’t even have cell phones. As a result, there wasn’t any conversations around social media or any hierarchy with status in terms of appearance or income or racial issues, gender identity, sexual identity. It’s very like, ‘If you show up, you’re considered family.’ That’s just not how urban queer culture is. We pride ourselves on being so advanced, but we’re actually really primitive and segregated within urban queer culture. The queer rodeo community is not like that.

AKEL: You’ve made the point, which I believe this book so powerfully illustrates, that you don’t think there’s ever been a singular American cowboy. Explain what you mean by that?

GILFORD: All of us who are a part of this country, in whatever way, find and build our lives in it. There are so many versions of the American cowboy. I hope that this project is a testament to that, to this sort of multiplicity of identities that intersect in America, all of whom are deserving of respect and dignity and safety and love.

AKEL: Looking at the images from National Anthem, the queer rodeo community is much more diverse than I had imagined.

GILFORD: Just like there’s no “American cowboy,” there’s no singular queer rodeo participant or spectator. How individuals come to the rodeo community reflects a diversity of experience. Some do not have relationships with their biological families—the rodeo is the only family they have. Others grew up competing in mainstream rodeo, but then discovered their queerness and no longer felt comfortable there and then joined this community. And then others are simply friends and family of the rodeo riders. Some of them are allies that are Black or Latino, or people of color who don’t feel comfortable in mainstream rodeo and became part of this community. There’s a lot of different narratives that intersect here.

AKEL: National Anthem was shot over a four-year period, and it’s clear from the candid quality the images possess, that you formed close relationships with the subjects you photographed.

GILFORD: The merit of an incredible portrait is really about connection. With the portraits that appear in National Anthem, I think there’s an admiration and a dignity that comes through. I’ve really spent a lot of time trying to get to know the subjects, becoming part of this family—this chosen family—over a period of time. In a very organic way, I took my time taking these portraits, allowing myself and the people I was photographing to build an architecture for connection—through telling stories, through asking questions, through body language, through smiles and gestures and really building trust in ways that are non-traditional, too. It was really important for me to ensure that this work did not feel objectifying or exploitative in any way. For example, the cover image was taken three years into the project. I didn’t just come in there and take it; it was shot pretty close to the end of the project. I think that a level of trust and intimacy is very evident in the picture. I can feel it.