Remembering Nora Ephron

In When Harry Met Sally, it takes 12 years for the titular characters to realize that they are in love—five years to realize that they are even in like—and yet, more than any struck-by-lightning fairytale, it is one of the most romantic films of the past 30 years.

Sally‘s writer Nora Ephron was, herself, married three times. “Never marry a man you wouldn’t want to be divorced from,” she quipped in her 2006 book I Feel Bad About My Neck. Not quite what you’d expect from one so associated with light romantic comedies. Indeed, if you find some of her Oscar-nominated films, such as Sleepless in Seattle, too mushy, you should try reading one of her books or essays; for when it came to writing about herself, Ephron was at once hilarious, self-deprecating, honest-seeming, and compassionate. In “What I Wish I’d Known,” Ephron doled out mildly acerbic advice such as “When your children are teenagers, it’s important to have a dog so that someone in the house is happy to see you,” and, “If friends ask you to be their child’s guardian in case they die in a plane crash, you can say no.” If you’re ever having trouble relating to a friend going through a divorce, Nora’s 1983 novel Heartburn (1983), based on her divorce from her second husband, journalist Carl Bernstein, will make you empathize whether you want to or not.

When we heard of Ephron’s death from leukemia yesterday at age 71, we were heartbroken to lose one of our favorite writers, directors, essayists, and feminists. Below we have reprinted an interview from April 2000, where Nora talks to actor Edward Norton about his directorial debut, Keeping the Faith, and why she began directing her own screenplays after 1990’s My Blue Heaven.

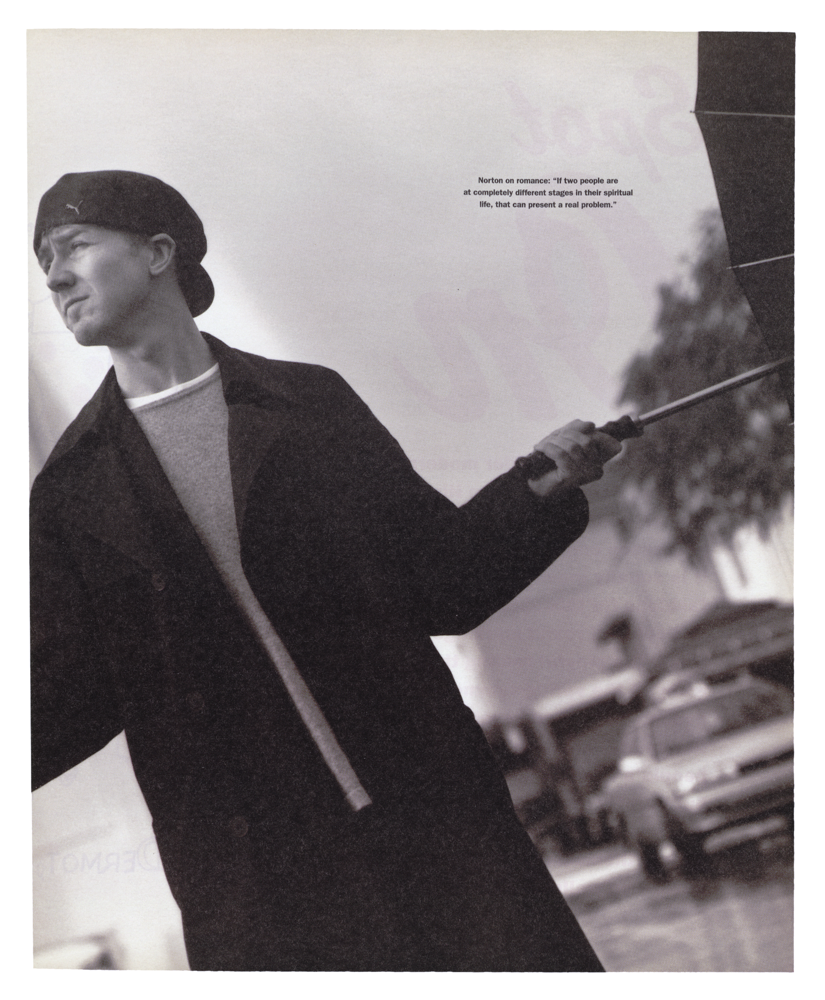

Edward Norton

By Nora Ephron

Moviegoers know that Edward Norton is an intelligent actor specializing in drama. But with the release this month of Keeping the Faith, they are about to discover that he is an equally gifted director—of comedy. Here he talks to writer, director, and comedy maven Nora Ephron.

NORA EPHRON: If I had to guess what your first movie was going to be about, I would have said a tortured young man growing up. Why have you, the famous prince of darkness, decided to do something so sunny and romantic?

EDWARD NORTON: A good friend of mine once told me that she thought our generation has dark-cool-irony disease.

EPHRON: Or post-irony: my favorite word this month, even though I don’t quite know what is means.

NORTON: This particular friend said, “Do us all a favor and don’t get caught up in the cliché of the dark, tortured, intense roles.” What has always been most interesting about acting to me personally is that it affords you the chance to shift gears, both in terms of the experiences you get to have through doing it, but also the different kinds of things you get to represent. I had just done American History X (1998), Rounders (1998), and Fight Club (1999). I was very, very emotionally ready to shift gears and work on something that had a different tone. To be totally honest, I was even a little surprised that I was doing this movie. I look at it sometimes and get this pang, or this kind of lance—I don’t know what the feeling is—but I look at it and go, I can’t believe I’ve made this movie. Part of it was just the happy circumstance that an old, old friend of mine, Stuart Blumberg, wrote a script that was really terrific, and we had an opportunity to make a movie together, which was something we had wanted to do since we were 18.

EPHRON: Were you always going to be in it?

NORTON: No. Stu had worked as an investment banker at Morgan Stanley for two years after we got out of school, and I was acting. He quit to follow his dream of writing and making movies. After a number of years struggling in New York and then working for a television show in Los Angeles, he came to me and said, ” I don’t think I can hack it any more. I’m going to law school.” I said, “I won’t permit it. You are a writer and you want to make movies and you just have to keep at it. Quit the job, sit down, spend the next six months writing, and we’ll work on getting it set up.” So right around the time that I finished American History X, he came to me with the first draft of this script, and it was so funny. It really made me laugh. We worked and worked on it, and the more we worked, the more it became our thing together. When you were writing, didn’t you ever hit a point where you felt, If I am going to write these things, I want to do them myself? Isn’t that what got you into directing?

EPHRON: No. What got me into directing was that it was such a nightmare finding a director, because it was like some kind of terrible marital thing that I was looking for: Who was going to fall in love with this piece of material I had created? And understand it and not bend it out of shape? Particularly since some of the time, what I was doing was something that was about a woman, and there weren’t that many guys directing who cared about women. It became this process of bending scripts slightly out of shape in order to convince some fabulous man that he ought to commit to it. There is just a certain point where you go, “Why not me?”

NORTON: Exactly. The truth is, it was more that feeling of almost creative ownership than it was deep connection to any one of the themes in the movie that made me decide to direct. Although there is this one thing that Stu wrote, where Ben [Stiller] and I are walking away from the camera and I say something like, “I was starting to think I had a few things figured out,” and he says, “I know, me too.” In this little scene, there’s this window on that experience of getting to be 30 and feeling like you’ve made it to a certain level of success, and then having things happen that just completely level you.

EPHRON: What do you think the movie is about, now that you’ve made it?

NORTON: Part of the weird thing about this movie is that it has a strange balance of things in it. It is not a pure romantic comedy. When you first read the script, Nora, you said, “You are doing a story about a rabbi and a priest and you are avoiding the subject of God. You can’t avoid talking about God.” That means from the get-go that it is not a pure romantic comedy. It’s got something else going on in it, which is—without bogging down in it, hopefully—a substantive discussion of faith.

EPHRON: Can you imagine, personally, religion ever standing in the way of love?

NORTON: No, I can’t. But I think that if two people are at completely different stages in their spiritual life, that can present a real problem.

EPHRON: When I was young, I had this list of things that I wanted in a husband. I knew what he should read and what sports he should like and blah, blah, blah. But the truth is, that the list was a shocking mirror image of me. You want to marry yourself when you are young. That’s what I love about all the personal ads. “Wishes to meet: non-smoker, skier, Democrat … ” Whatever it is, it’s who they are.

NORTON: “Single white male seeking single white female version of self.”

EPHRON: Exactly. All the things you think are so urgently important, when you get older, you discover they don’t have anything to do with love.

NORTON: [Rainer Maria] Rilke said a great thing about how when you are young, you perceive a relationship as a fusion. When people come together too young, they try to become one person. As you get older, you realize that you don’t want to become one person because then you lose the person you are. Rilke’s whole idea was that a good relationship is two people who stand guard at the gates of each other’s solitude or singularity.

EPRHON: Let me ask you a couple of things about directing: Who inspired you? Who was the angel on your shoulder?

NORTON: On one pole, I’d say Milos Forman [who directed Norton in The People Vs. Larry Flynt (1996)], and at the complete opposite end of the spectrum, David Fincher [Fight Club]. They’re the two directors I worked with from whom I absorbed the most about what the job entails, and they were the two people who in totally different ways impressed me the most with their grasp of what the job really is and their talents. There were things about the actors and the kind of film Faith is that absolutely needed some of the looseness and organic, exploratory style that Milos works in and that takes a lot of confidence, I realized. But Milos can afford to do that. I was trying to shoot 82 locations in New York City in 62 days. For that reason, I had to incorporate a lot of what I call the David Fincher component, which is to say that he is probably the best comprehensive director in terms of being a manger of a process that must drive forward. I’ve never seen any single individual be the visionary engine that created momentum on a film over all obstacles. He has such confident command of cinema language and visual language and script and performance and everything, that he sometimes can border on being a micro-manager. He knows more about f-stops than any cameraman, he knows more about lighting than any gaffer, he is a wonderful writer, and he can give you a good line reading. Under pressure, he is the kind of guy who you will just dive in with and trust and follow because his vision is so intense. He came to see this film and I was a little nervous, because if I am the prince of darkness, then he is the king of darkness. The thing he liked most about it was the tone.

EPHRON: I wouldn’t use the word tone, but I think it’s true, your movie finds its reality very early.

NORTON: Don’t you think that is what directing is all about? To me, achieving tone, achieving consistency, is exactly your job as a director. Your job is to be the fusing, the nexus of a whole bunch of people contributing to the complex life of a movie. There are actors, there’s a cinematographer, there’re costume people, set people, there are all these things, and you somehow have to be the person in the middle of it who is making it all synchronize into the same magic bubble.

EPHRON: Do you think a romantic comedy is harder or just different?

NORTON: I think it’s different. I do subscribe to the maxim that generally comedy is like jazz. Either you get it or you don’t. You can’t learn it and you can’t be taught it. I think there are different kinds of comedy and people have their own brands that they understand or don’t understand, but I don’t think that if you are not a funny person, you can fake it.

EPHRON: You do become very hooked on the gifts of actors who can make things funny, who can find funny where it’s possible to find it.

NORTON: Ben Stiller’s like that. Ben Stiller can make a conversation that is not funny, funny. Did romantic comedies mean more to you than other types of movies when you were younger?

EPHRON: No, I don’t think so. There is no question that my favorite movies as a kid were the whole series of movies that Audrey Hepburn made, especially with Stanley Donen. I didn’t see It Happened One Night [1934], which I think is one of the greatest romantic comedies ever, ever, ever made, until I was in my twenties. I always say this: having been married so many times, I know that one of the few things I am an expert in is falling in love.

NORTON: See, I am not young enough that I can say I grew up on When Harry Met Sally [1989]. I grew up in a period when it was the pits for romantic comedies. For me it was Woody Allen films. The it was a process of going back to films like The Philadelphia Story [1940], which was definitely in my head making this movie because Ben Stiller’s character is a lot like Katharine Hepburn’s character, in the sense that she is the bronze goddess. I think that Jenna Elfman is Cary Grant in our movie in the sense that Cary Grant is there to be perfect and look great in suits and for us to know from the minute he walks into the movie that that is who Katharine Hepburn is supposed to be with.

EPHRON: And who do you think you are?

NORTON: Jimmy Stewart. I think that romantic comedies can be marked pre-Annie Hall [1977] or post-Annie Hall. Annie Hall started the romantic comedies that are about romance…

EPHRON: Or analyzing romance. To me, Annie Hall was the first Jewish romantic comedy in that the obstacle to love was the neurosis of the male protagonist.

NORTON: Annie Hall started a new thing, even though in the broad mainstream people didn’t catch on because it was too rarefied for most audiences. And then, When Harry Met Sally took what Annie Hall started, which is to say the Jewish romantic comedy or the self-aware romantic comedy, and made a big success out of it.

EPHRON: It was a movie that was essentially about whether a man can love.

NORTON: But When Harry Met Sally wasn’t just about the man’s inability. What When Harry Met Sally really kicked off was the idea of the modern romantic comedy, because nobody called Philadelphia Story, or His Girl Friday, or Bringing Up Baby [1938] romantic comedies. They called them screwballs. We didn’t start calling them romantic comedies until after When Harry Met Sally. But the post-Annie Hall, post-When Harry Met Sally romantic comedy has been a different kind of thing, in the sense that the point of the film has been the romance, or the analysis of that romance, and the analysis of the obstacles to romance.

EPHRON: Right, because as the obstacle of class ceases to exist in post-World War II America, where anyone can marry anybody, you have to find new obstacles. So the exterior obstacles all become interior. What always amused me about Sleepless in Seattle [directed by Ephron, 1993] was that it had to find the most contemporary obstacle of all, which was that the people in love don’t know each other.

NORTON: Do you think that’s the key to all romantic comedy: the identifying of the obstacle?

EPHRON: I do think it’s hard to have one without it.

NORTON: A lot of the romantic comedies that have been put out in my generation wall in their hurt. Stu said from the beginning, “I want these characters to be people with a lot of conviction, and passion, who are not afraid of romance.” The obstacle is not their own internal angst. They’re pro-actively positive, enjoyable, passionate, vigorous people of our age, who are not just these aimless, low-energy, angst-ridden Gen X slackers who can’t find love because they can’t get it together to do anything. It gets back to your initial question, which is, “Why did I make this kind of movie?” I just felt like Fight Club was the last needle in the eye of the twentieth century, the last really savage critique of everything that we fucked up. And Keeping the Faith was the perfect movie to do in the year 2000.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN THE APRIL 2000 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

For more New Again, click here.