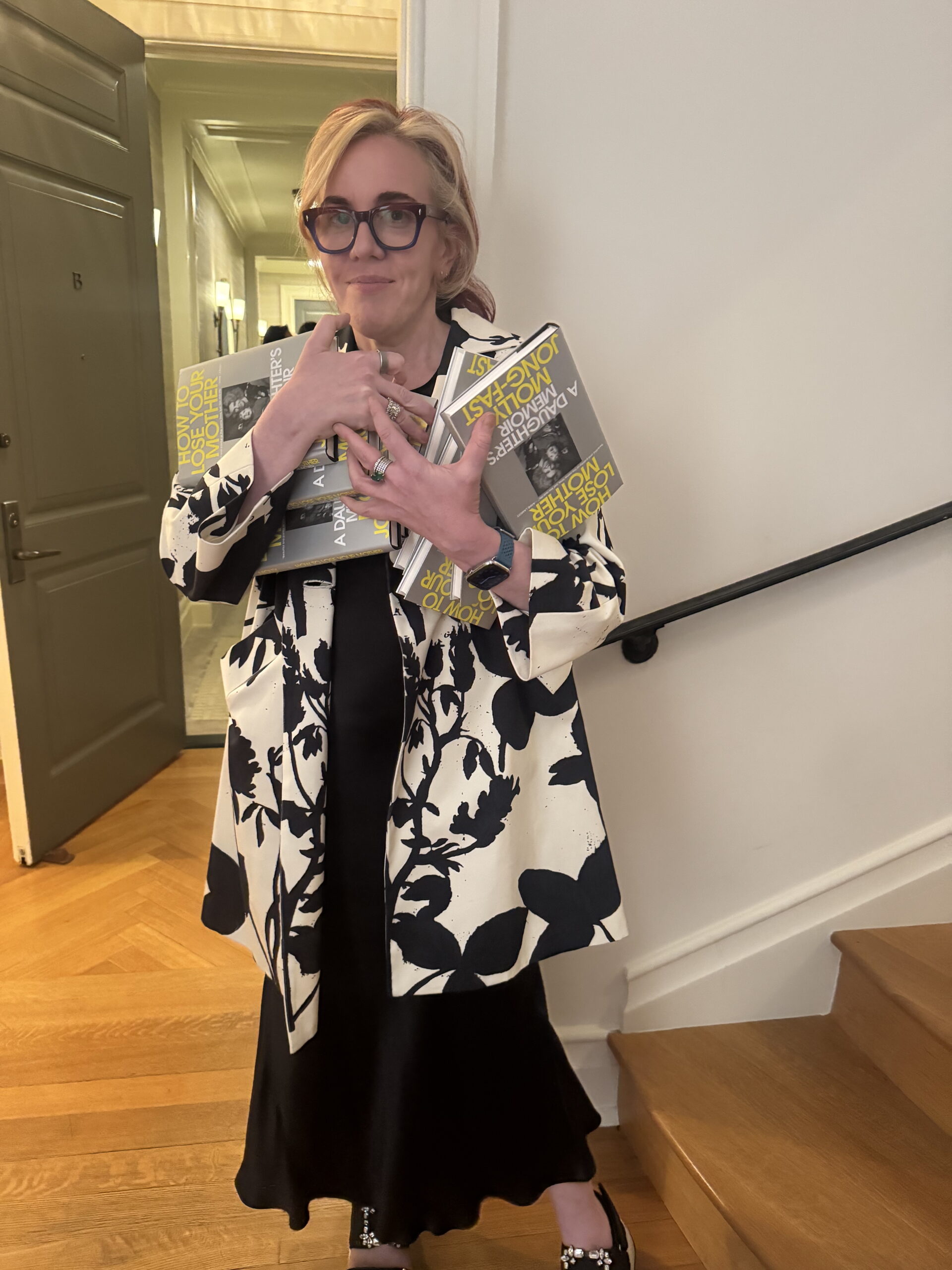

MOMMY ISSUES

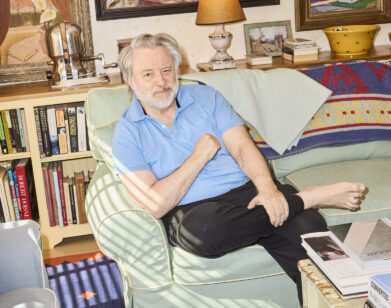

Molly Jong-Fast and Jay McInerney on the Price of Literary Immortality

“Fame, like alcoholism, rings a bell in you that can never be unrung,” Molly Jong-Fast writes early on in How To Lose Your Mother, her sharp and sobering new memoir out this week. The line sets her up to unpack the complicated legacy of her mother, Erica Jong, whose 1973 blockbuster novel Fear of Flying made her a feminist literary icon—and, as it turns out, a huge nightmare for those in her personal and professional orbit. In her daughter’s retelling, Jong emerges less as a fearless thinker and trailblazer and more like a narcissist grappling with addiction, a string of bad relationships, and her fading star. “Literary immortality is a very strange, strange thing,” the beloved novelist Jay McInerney mused when he caught up with Jong-Fast last month. In conversation, the two went deep on the ephemeral nature of fame, the old crowd of writers who once gathered at Elaine’s, and the many fascinating and peculiar facets of Erica Jong.

———

MOLLY JONG-FAST: I’m wearing thick TV makeup, so–

JAY MCINERNEY: Where were you on TV?

JONG-FAST: I do Morning Joe, usually on Tuesdays and Thursdays.

MCINERNEY: Oh. I wasn’t watching this morning, but yes, I’ve seen you on Morning Joe. So of course I read your book. It raised a lot of interesting questions for me, even though I am not the daughter of a famous mother. You start off with the issue of fame, and one of the best lines in the book comes very early when you say, “Fame, like alcoholism, rings a bell in you that can never be unrung.” What do you think your mom would have been like if she hadn’t been famous? Surely she would have been a little abstracted and emotionally unavailable anyway?

JONG-FAST: I think about that a lot. I often wonder what would have happened had she stayed in grad school, finished her dissertation, and became an academic, maybe a poet on the side. She had some weird self-destructive impulses that she could not get over, and that was a real problem for her. There’s always a difference between the person you meet publicly and who they are at home, right?

MCINERNEY: It sounds very fraught.

JONG-FAST: Wait, I want to tell you something about fame first–I’ve been dying to mention this to you. I was at this screening of Friends and Neighbors, which is written so well by Jonathan Tropper. I said to him, “You write incredibly well. It’s rare for TV to be this good.” And he said, “You know who my greatest inspiration is?” I said, “Who?” And he said, “Jay McInerney.”

MCINERNEY: Wow, that’s quite a compliment. I do think the show’s really well written.

JONG-FAST: He said once a year, he reads Bright Lights, Big City.

MCINERNEY: It’s funny, when people say things like that, they often add, “Well, you’re probably tired of hearing that.” But I think, “Whoever gets tired of hearing compliments!?”

JONG-FAST: Especially about writing, when nobody reads anymore. I also think tight prose is something that’s not even valued in our culture these days.

MCINERNEY: Well, that leads me to another question. In your book, you say several times that you didn’t read your mother’s work. But did you ever go back and read Fear of Flying, or some of the others?

JONG-FAST: I was on a trip with my mom to Heidelberg for a documentary, because she lived there during the Vietnam War when she was married to poor Allan Jong–whose life few people have had more ruined by a writer. I started reading Fear of Flying and realized every single thing in the book had happened. I thought, “No, I’m out. I can’t.” And since then, never. But my husband reads them and looks for stuff about him or me, then is horrified.

MCINERNEY: It’s funny, my son reads my work and talks to me about it. But my daughter won’t read my books because she’s terrified of coming across something, like a character based on me having sex. I think that’s what it is.

JONG-FAST: That’s right. By the way, can we talk about Brightness Falls? It’s such a good book. It feels like your foray into Tom Wolfe territory.

MCINERNEY: Well, honestly, it’s more Thackeray and Balzac than Tom Wolfe.

JONG-FAST: But isn’t Tom Wolfe trying to be Thackeray? Aren’t we all trying to be Thackeray when it comes to novels?

MCINERNEY: I remember Tom coming up to me at some dinner and saying that I was very clever to have taken New York City as a subject and setting. This must have been ’86 or something. But the funny thing is, when I wrote Bright Lights, Big City, my publisher said, “Nobody wants to read about New York.” When Bright Lights was published, there had been very few novels set in New York since Catcher in the Rye. Then suddenly there was a rash of them, of course.

JONG-FAST: Well in my heart, your career is the career. I did something different because those doors opened for me in a way that the fiction door didn’t, but I still bang my head on it.

MCINERNEY: I have to say that one of the things I recognized in your writing about your mom is that, I used to be very famous. I’m not so famous anymore. Fortunately, I don’t think it’s crippled me, but I was really interested to read the way in which you felt that it had crippled your mom. And I think the other big theme in this book is alcoholism. You say that it runs in the family, and certainly your mother was an alcoholic.

JONG-FAST: Oh yeah, one of the greats. One of the things that I get to do now in my career is, people come to me and they tell me terrible stories about my mother.

MCINERNEY: Oh, really?

JONG-FAST: This fabulous political writer who I know, smoking a joint, so drunk, comes to me and says, “I was the head of this thing in the UK and we had your mother speak. I’ve never met anyone so drunk in my life.” I was like, “You are smoking a joint right now. How is she the most drunk person you’ve ever met?”

MCINERNEY: Well, as I recall, my encounters with her, I did not notice her being drunk. But then again, we were all pretty buzzed one way or another back in the ’80s.

JONG-FAST: Yeah, exactly.

MCINERNEY: Which is when I first met her in the way that one does in the literary world and in the world of New York celebrity. But certainly, she could be very charming and very friendly, and very flirty too, by the way. But I always had a good impression of her, and yet I can’t help thinking it must’ve been really hard to grow up in this household that you did. And not least because your stepfather seems to have been in denial about many things.

JONG-FAST: It’s funny, so many of the things that happened during my childhood, when I had kids, they would say, “These are the things you absolutely should never do.” And I was like, “Oh, my parents did that.” Part of it is the ’70s. Now, parenting is all about staring at your child and making sure they have a good experience in the world. Back then, everybody was smoking and we didn’t have car seats. It was a different mentality. So I fault her, but then I don’t. But she had all these fiance’s, and she was always engaged. You’d meet these people and you’d think, “Oh my God, this guy’s going to be my father!? This asshole?” And she’d pick these people where you’d be like, “You will not be happy with this person. This is a guy from South Carolina who plays golf. This is not the Erica Jong I know.”

AY MCINERNEY: So she was what we would call a player, I guess.

JONG-FAST: She also had these incredible affairs. She was with this guy, the editor of Artforum, who was this fabulous Italian guy. She had this affair with a very rich Republican donor who actually is still alive, but very old. And he’s so rich. Our whole lives, we were just panicked. My whole life, my mom would be like, “I spent all the money. We have no money. We’re going to have to sell everything.” Being a writer, you live book to book, it’s a disaster. You spend your advance. And so then she starts this affair with this very, very rich guy, and she says, “I can never be with him, he’s a Republican.”

AY MCINERNEY: Yeah, I was going to ask you if she was very political, actually.

JONG-FAST: She was not even that political, but she was like, “I could never be with a Republican.” She was a very avowed atheist, but very superstitious and crazy, as one is.

MCINERNEY: Oh, wow.

JONG-FAST: So yeah, pretty bad. But it is interesting to me to think of that time in the ’80s at Elaine’s, ‘ cause my mom and Elaine [Kaufman] hated each other.

MCINERNEY: Well, Elaine hated most women. She did.

JONG-FAST: Yeah, I know.

MCINERNEY: She would pretty much ignore women.

JONG-FAST: What do you miss about that time? It feels like such a singular moment in American letters.

MCINERNEY: I do miss that time in many ways, because there was more of a literary center then, certainly. And Elaine’s was a real gathering spot where I would just regularly see other writers. Most of them were older than me, but Gay Talese and Robert Stone, and for a while, William Styron. And the journalists, Pete Hamill and Jimmy Breslin and people like that. And then you also had George Plimpton’s townhouse, which was the headquarters of The Paris Review. He would have these parties where you’d meet all these really pretty girls and older writers.

JONG-FAST: Salman [Rushdie] also was a–I mean that whole world, and Norman Mailer. Who do you think of that crew?

MCINERNEY: Mailer was a good friend of mine. I spent a lot of time with him and he had all kinds of advice. One of the most interesting things he ever said to me was, we were walking away from a screening and there were a lot of photographers snapping away. He turned to me and he said, “Jay, watch out for those flashbulbs, they will bleach your soul.” Which kind of relates to your observations about your mother and fame, and the addictive nature of fame.

JONG-FAST: Can I ask you a question?

MCINERNEY: Sure.

JONG-FAST: When you think of the sort of people who are lost to history–Mailer in a certain way kind of is. And my mother was very close with Henry Miller, he’s sort of still, and I feel like–

MCINERNEY: I think Henry Miller is still in the conversation. But I was thinking yesterday about Mailer and kind of wondering whether he would somehow remain in the conversation. Another person who really almost disappeared, who I believe was a fan of your mom’s, was John Updike.

JONG-FAST: Yes, I was just talking about Updike.

MCINERNEY: I think he and Roth were the most famous literary writers at a certain point in my youth. It just seemed like Updike would never go away, but people don’t talk about him anymore. Literary immortality is a very strange, strange thing. Somebody from the BBC was asking me yesterday about John Dos Passos in the ’30s, when Fitzgerald couldn’t get arrested, Dos Passos was probably considered the great American writer, and now, nobody can even remember him. It’s a fleeting thing. Do you think your mom worried about posterity?

JONG-FAST: All she cared about was posterity. She would be like, “You are my literary executor.” And by the way, when people ask me what she would think of this book, all she wanted was to matter when she died. This is why we do it, for immortality, at least when it comes to writing. There were two things she desperately wanted in her life: One was to make it, to get that fame and to stay there, but the other was to really make it in academia. So many things created this pool of dysfunction that made her obsessed with her own fame, and a lot of it stemmed from her fixation on the academy and never feeling like she truly made it there. Though she’d probably argue she did make it, given her level of fame. She was very narcissistic, while the rest of us just feel terrible about ourselves all the time, right?

MCINERNEY: When did you start noticing that maybe her fame had faded from its peak? Fear of Flying was published in ’73, before you were born, but I imagine its impact reverberated for quite a while.

JONG-FAST: It’s funny, there was a little blurb in The Times about upcoming books, including mine, that mentioned Mom’s work. These days, you’re supposed to self-promote, especially on social media. But back then, you really weren’t supposed to, particularly as a writer. And she did, in a very cringeworthy, narcissistic way that people deservedly mocked her for. I think that hurt her legacy. Norman Mailer did iconic things, though not without issues from today’s lens, and I’m not sure a Mailer type would fly now as a feminist. But his writing was excellent and he delved into fascinating subjects. Mom, on the other hand, behaved in a way more fitting for current times than that era.

MCINERNEY: Good point about Mailer being a self-promoter too, no question.

JONG-FAST: True, but he pulled off amazing stunts. Some bad, some incredible.

MCINERNEY: Some very bad, indeed.

JONG-FAST: It’s weird, we’re in these cycles of cultural backlash. We discover wrongs, get furious, then move on to the next outrage. Looking back, that time produced a lot of great writing, but some of it is definitely not okay anymore.

MCINERNEY: The sexism of that era, even when I was growing up… I guess Erica Jong really emerged in ’73 when I was in college, but feminism still wasn’t mainstream.

JONG-FAST: The pill only became legal in 1964, then in ’73 you had Roe v. Wade and several legislative wins for women.

MCINERNEY: [Laughs] Things don’t look good on that front now.

JONG-FAST: Let the record show, we laugh to keep from crying.

MCINERNEY: Yeah. This is a horrendous moment in American history. Is your mom aware this book is being published?

JONG-FAST: I’ve told her and even given her a copy, but her memory resets like Groundhog Day. The tragedy isn’t just the memory loss, though that is tragic. She’s 84 and otherwise healthy, but took handfuls of Valium for years. Didn’t happen by accident. I wish she had a surviving husband to take her to parties, because while she’s not all there, she’s still lovely and delightful.

MCINERNEY: So you can’t really converse with her anymore?

JONG-FAST: No, it’s quite dark. It’s disturbing for me because I think of her as so smart. But she’s healthy. Makes you ponder what quality of life really means.

MCINERNEY: Sometimes in the book you protest a bit too much about loving her. You’ll write three pages of heavy material then seemingly feel guilty and profess your love. Feels like something’s off there.

JONG-FAST: It’s certainly true that I’m haunted by her. Writing this book, I was struck by how stuck I was in my childhood, unable to move past it. My husband has a powerful same-sex parent who passed during the writing process, and we both struggled to get out from the shadows of these more successful parents blocking the sun. Watching my husband get cancer made me realize how short our time is.

MCINERNEY: We haven’t really discussed you facing that dual tragedy. Thankfully the title tipped me off that your husband survived.

JONG-FAST: Ha, yes, otherwise it’d be “How to Lose a Husband AND a Mother.”

MCINERNEY: It reminded me of my 2022. I had brain surgery and a quadruple bypass, and spent 25 days in the hospital.

JONG-FAST: Wow, what happened? Heart attack?

MCINERNEY: No, first I passed out, hit my head, got a subdural hematoma that worsened until they told me to get to the hospital ASAP. I tried to delay it for a dinner reservation but they insisted. Very reluctantly had brain surgery. Months later, a stress test revealed 90% blockages, so another emergency trip for the bypass. Your hard year parallels mine in ways, but I love what you did with it in the book.

JONG-FAST: I’m struck that you seem 100% back to normal now, which is amazing.

MCINERNEY: I feel really good. Funny enough, after being blocked on the novel for months, I started writing 3,000 words per day in the hospital and finished it in a flash. Maybe they tweaked a circuit up there. When did you finish this book?

JONG-FAST: I think it was June, about a year ago, and they accepted it around September if I remember correctly. There was another book I was supposed to write, but then mom’s dementia began. Spending so much time on news and politics, I’m very focused on what matters–albeit in a myopic, strange way. Usually it’s what matters to voters in Iowa, not what truly matters in a broader sense. I knew this story could resonate with people beyond affluent city-dwelling Jews, that it could connect with a wider audience.

MCINERNEY: The mother-daughter relationship is universal, unless you lose your mother very young. But yours is simultaneously universal and unique, because of your mom’s fame.

JONG-FAST: It’s been tough for me, I’ve been very in my head about the meaning of aging. I was never a great beauty, never thought I’d mourn my youth, but I do anyway.

MCINERNEY: Well, look at it this way–Fitzgerald and Jane Austen died around your current age. You have a huge chunk of life left to make your mark, so go for it.

JONG-FAST: Thanks Jay, I appreciate that. Oh, you have to run. Thanks so much for this.