NOSTALGIA

How Photographer Will Vogt Captured the Seedy, Greedy Eighties on Camera

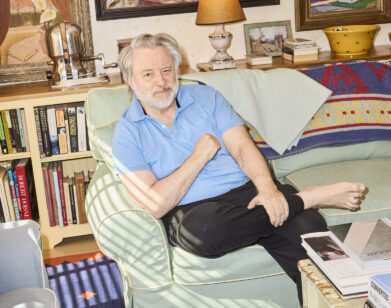

I became acquainted with Will Vogt as a result of our shared enthusiasm for the work of F. Scott Fitzgerald. We both collected first editions of his work, and at some point, after competing over one or two items at auction, we connected through a mutual friend and eventually had lunch together at Michael’s in midtown Manhattan, which must have been my idea, since it was and remains the lunchtime headquarters of the New York media world, the gathering place of my tribe. Vogt, when he is in Manhattan, frequents venerable men’s clubs like the Brook, founded in 1904, and the Leash, a former speakeasy for dog lovers located in a townhouse on East 63rd—both of which he belongs to, both of which Fitzgerald would have known. Now that I’ve seen his photographs, I can’t help thinking that he is documenting the world of the descendants of those whom Fitzgerald wrote about. And he is clearly a member of this tribe, albeit a self-aware and observant one.

These Americans shows us a privileged and insular world, one which is usually glimpsed from the outside, and regularly caricatured in films and fiction. Edith Wharton was the only great literary artist who was actually an initiate of the world of American wealth and privilege, although at this distance her characters seem antique. Fitzgerald wrote brilliantly about the America plutocracy—of observing this world as if from the other side of the glass, but he writes better about it than anyone since Wharton. (His short story The Rich Boy is one of his greatest accomplishments, its presentation of the world of inherited American wealth much more nuanced than in The Great Gatsby.) Clearly, there’s no pane of glass separating Vogt from his subjects. He’s right there in the ballroom, in the pool, on the boat, with his subjects.

Vogt’s photos in These Americans seem like snapshots from the album of a large, well-off American family in the latter half of the twentieth century. The subjects, most of whom have undoubtedly appeared in the society pages of local and national publications, are at ease in front of this particular camera. They are at home, they are at leisure, unafraid of judgement. They are often drunk, or, in some cases, high on cocaine, a drug which became very popular with elites in the nineteen eighties after emerging from the demimonde. It was a relatively expensive high, but these people could afford it. Cocaine undoubtedly had a role in encouraging some of the exhibitionist and erotic behavior exhibited herein. Vogt reminds us that it was a drug consumed in the bathrooms of country clubs as well as nightclubs. The razor blades and the plastic straws and the triple beam balance scale are like a time stamp on some of these photos, telling us that the people portrayed are not entirely immune to the tides and currents of fashion that mark their era. The lapels of their sports jackets become just a little wider in the seventies, just as they did in less rarefied venues. And yet… and yet, it’s striking how the signifiers of wealth and privilege here remain almost unchanged from Fitzgerald’s day—the boats, the pools, the hunting dogs, the sports cars, the exotic pets.

For the most part, these people are living in the world that their parents and their grandparents inhabited and created. They aren’t rebelling against the previous generation. The few black faces here are those of servants. Blood sport is a constant visual theme. Vogt’s camera doesn’t flinch from the gore—the bloody deer heads and carcasses, the piles of dead birds. As cheerful and carefree as many of the humans in these photos appear, the animal carcasses are memento mori, and there are undertones of dread here, as in the picture of a young shirtless blonde boy at a table with blueberries smeared all over his face and chest; at first glance the fruit could easily be mistaken for blood. A hunting dog snarls at another dog, baring a set of dangerous-looking teeth, while the humans in the frame talk to each other, as if unaware or unconcerned. So many of these photographs inspire speculation: why are these people naked with their heads covered? Why is this boy smeared with pie filling? Or, more prosaically — what was it that had just been said before Vogt snapped this couple with his Nikon. Few of these photos are posed. There is a sense of these lives being caught on the fly, in medias res.

These images give us a sense of spying on intimate moments, which imbues them with a certain tension and mystery. In this regard they’re very different than the photos of Slim Aarons, whose subject matter overlaps with Vogt’s. Aarons was born into a poor Yiddish-speaking family on the Lower East Side and most of his images of the American and international jet set are staged and artificial—he sought to glamorize the glamorous. (And usually succeeded.) Vogt’s relation to his subjects is much more intimate. He knows what they’re thinking and he knows that it may not be pretty. He knows who’s fucking whom, who cheats at golf, who starts drinking at eleven in the morning. But he’ll take them as they are. They’re his people. And he shows them to us in a way that no one else has. I suspect Fitzgerald would have been impressed.—JAY McINERNEY

———

Interview with Will Vogt conducted by Apple Martin

“I always thought that I could get better pictures than the wedding photographer because I knew who the people were and I knew who was really important. So that was my goal. I was not the professional; I was a wedding guest that wasn’t dressed in different clothes with the big cameras saying, ‘Oh, hey, stand here, stand over there, get together.'”

———

“I hitchhiked across the country in the early seventies and took a lot of pictures and went on some crazy road trips. But soon after, I started realizing that Robert Frank had done that. So I really started to concentrate on my own world and my own friends and what I saw.”

———

“It was a different era. Obviously, there were victims of that freedom and that lack of knowledge. But I think while it was going on, it was pretty great, fun, and maybe not as dramatic as the things that went on in the late sixties and early seventies. The eighties were a pretty good time, really.”

———

“If you go back to the very beginning, it was really my mother [who drew me to photography]. It’s the way the world works, isn’t it? In the fifties, she took family pictures and pictures of her friends. But more importantly, she put them into albums and curated this family and personal history. I was always fascinated by that. I think that was really the beginning of it all.”

———

“There’s definitely some nostalgia involved in it because some of the principal players in the book are gone. I think if I had any feelings at all, it was a nostalgia for those times and those people.”

———

“There’s hardly anybody in that book that I didn’t have some kind of a relationship at one time or another. Those are not strangers.”

———

“The eighties were a much more carefree time in America and everywhere, and not just for one class of people. The world was not as politically correct. People expressed themselves more freely without worrying about what other people thought, for better or for worse. Obviously, you can tell from the book that people did drugs, and drugs didn’t kill you in those days. They might have made you stupid, or made you make bad decisions, but I don’t think anybody was going to do a big rip and fall right on the ground, dead.”

———

“We decide against captions because we were really trying to stay away from, who’s that? what’s that? what’s that mean? We really wanted the people that are looking at the photographs to make their own decisions about what they’re seeing.”

———

“The tiger’s name was Muffy, the pet of a very legendary South Texas character. He lived a very colorful life and he kept Muffy at his ranch house in the backyard, fenced in. A 400 pound Bengal tiger.”

———

“I was the gunslinger. I had two cameras in one in each pocket and went through all these point-and-shoot cameras for years. People were not worried where [the photograph] was going to go, because there was no posting immediately to social media.”

———

“My wife said, ‘Well, maybe you should do one of the nineties next.’ I’m like, ‘Well, I don’t know that the nineties were that exciting.’ So who knows what comes next, but I think something will.”

———