LEGEND

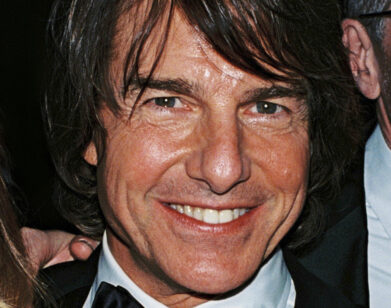

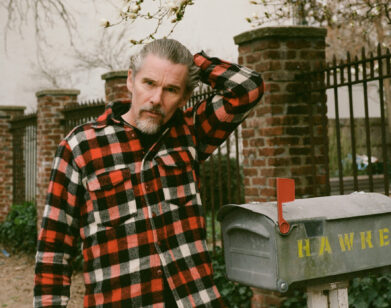

Sissy Spacek and Ethan Hawke Enter the Flow State

Sissy Spacek first stole hearts twirling a baton in Badlands, then helped rewrite American cinema with ’70s classics like Carrie, 3 Women, and Coal Miner’s Daughter, which earned her an Oscar for Best Actress. At 76, she radiates a down-to-earth sincerity that feels a world away from Hollywood. This fall, Spacek returns in Lynne Ramsay’s Die, My Love, opposite Jennifer Lawrence, Robert Pattinson, and Nick Nolte. During her promo tour, she met up with fellow Texan and longtime fan Ethan Hawke for dinner at Wolfgang Puck’s steakhouse in Tribeca, who came armed with questions about her five-decade career. Somehow, the two have never worked together, but they still had plenty to talk about, from acting to aging, to the late great Diane Keaton.

———

THURSDAY 7 PM SEPT. 30,2025 NYC

ETHAN HAWKE: I’m going to start us off officially, so the recording device can know, and they’re going to have to edit this and make it interesting.

SISSY SPACEK: It’s going to be interesting. You’re here.

HAWKE: Here’s the thing. I feel incredibly proud of myself at this moment, because I know one of your past Interview interviews was conducted by none other than Andy Warhol.

SPACEK: [Laughs] That’s true.

HAWKE: What was it like to be interviewed by Andy Warhol?

SPACEK: I don’t know what my preconceived idea was, but I thought, “Wow, crazy artist!” He was such a gentleman and so dear to me. Nice and polite to my mother who was with me.

HAWKE: And tonight you have your daughter with you.

SPACEK: I’m lucky.

HAWKE: We’re very lucky.

SPACEK: You have four children.

HAWKE: Yeah. You have two?

SPACEK: I have two girls.

HAWKE: I have a boy and three girls.

SPACEK: Well, they’ll take care of you when you’re an old man.

HAWKE: Let’s hope so.

SPACEK: At least one of them will.

HAWKE: That’s what I hope.

SPACEK: They’ll take turns.

HAWKE: Here’s a really boring question that I’m sure everybody’s asked you, but my family, we’re all from Fort Worth.

SPACEK: Oh my god! How did I not know that?

HAWKE: Because it’s not your job to know everything about me. My mother, her name is Leslie, but the people in her family called her Sister. Did Sissy come from being called sister?

SPACEK: My brothers.

HAWKE: Yeah.

SPACEK: My real name is Mary Elizabeth, and when I started school in first grade, they said, “Is it Mary or Elizabeth?” I knew at that moment I had to fight for my name because my brothers who I idolized—

SPEAKER 3: Can I order you anything beverage-wise?

HAWKE: I’m going to have the lobster spaghetti and the cappuccino.

SPACEK: Could I have a little salad? A little house salad with vinaigrette?

SPACEK: Thank you. That’s a common Southern nickname for girls. In fact, when I was working on Coal Miner’s Daughter and they’d call Sissy on the set, there was a stampede. Every little girl was nicknamed Sissy.

HAWKE: [Laughs] Well, my oldest daughter—

SPACEK: Maya.

HAWKE: When she was falling in love with acting and getting serious about it, I said to her, “If you’re going to do this—have you seen Coal Miner’s Daughter?” And she said, “No.” So I said, “Well, we’re going to sit down tonight and watch it.” And we had such a great evening. I saw Coal Miner’s Daughter in the theater on my birthday, when it first came out.

SPACEK: How old were you in 1980?

HAWKE: I was 10. I remember because I was raised by a single mom and she was away working. She had this new boyfriend, and he was alone with me on my birthday. And he said, “What do you want to do?” I said, “I want to go see Coal Miner’s Daughter.” So he took me.

SPACEK: God bless him.

HAWKE: It made a very lasting impression. I’ve always thought of it as the best music movie. There’s a couple of good ones, but yours is my favorite. I felt it was a high-water mark of what a performance could be.

SPACEK: Oh my god, thank you. Loretta [Lynn] was incredible. Part of the beauty of that film was Loretta herself, plus the writer of the book and the way she told the stories, and the director, Michael Apted.

HAWKE: I got to audition for him once. I loved him.

SPACEK: He knew how to set up a shot. Not by saying, “You go over here. You go over there.” He’d say, “Where do you think you would be? Feel it out.” And he and the cinematographer would watch. They designed the shot around what we naturally felt like doing, so it was organic.

HAWKE: All the best directors do that. They adjust according to what’s really happening. I realize as I’m speaking to you—I think that’s where I fell in love with Levon Helm. I named my son after him.

SPACEK: What a thrill it was to work with him on his first acting job. He was such a natural. We were dumbfounded.

HAWKE: At what point in your career did that movie happen to you? You’d already done Badlands. You’d already done Carrie.

SPACEK: Carrie was 1976, Badlands was 1973, and Coal Miner’s Daughter was 1980. I went into it knowing nothing. I’d had a little bit of training at the [Lee] Strasberg Institute in New York.

HAWKE: My brain is exploding with questions for you, but in my family, no one else was an actor. In your family, how aware of Rip Torn were you?

SPACEK: We were close as a family. He was my first cousin, and he was older than me. He took a$er the men in my father’s family. He would come through and fish, so acting seemed like a possibility because I heard the family stories about him going to New York. But I was a musician, and that was my path. I never wanted to embarrass Rip by acting, so I waited until I just stumbled into it.

HAWKE: What role does music play in your life now?

SPACEK: I love music. I sing in the shower. My daughter’s a musician. My dad was a musician. He was a really great four-string banjo player, but at a certain point he stopped playing because he was busy working and raising a family. I thought, “Wow, how can he just give that up?” But I’ve given up playing the guitar.

HAWKE: Why?

SPACEK: I got busy raising my girls and being on a farm and trying to keep a career going. There was one long period of time that I didn’t play and then I picked up 12-string, and I was really into it but I wasn’t as good anymore. I’d stopped progressing. So rather than take the time to push through that, I didn’t. But I started singing harmony for Schuyler [Fisk, Spacek’s daughter].

HAWKE: Is that fun?

SPACEK: Oh, it’s so fun. Have you ever sung in harmony? I’m sure you have.

HAWKE: Yeah, I have. One of the things that’s stifled my musicianship, because I’ve never been very good, is my children’s development. They’re such far superior musicians. And actually, I’m much more interested in their musical life than my own.

SPACEK: It’s so true. But it took me where I didn’t even know I wanted to go. The thing I experienced first in music was the flow state. It was an incredible thing. And then when I started acting, I experienced it in—

HAWKE: Performance.

SPACEK: Not always.

HAWKE: Certainly not always.

SPACEK: Sometimes.

HAWKE: Can you remember the first time you felt it as an actor?

SPACEK: God.

HAWKE: I can. I got a job with Robin Williams in this movie Dead Poets Society. I had to do a scene where the director wanted it in one take. The Steadicam was a new camera tool and it was exciting to him. We were doing this take with Robin, who, as everybody in the world knows, was very improvisational and wild and eccentric. And I was 18. We did this take where I had to make up a poem in front of the class, and we did it over and over again until I felt myself disappear.

SPACEK: Isn’t it just—

HAWKE: It’s such a magical thing, because what I find so mysterious about acting is that people tend to celebrate your personality, like, “You’re wonderful.” And the irony is that when it’s good, you disappear.

SPACEK: And you don’t even know what you’ve done. You know how they say, “That was great. Do it again?” It’s like, “What did I do? Where am I? What just happened?” Don’t you think that’s why we do it?

HAWKE: Absolutely. I had that one experience on set when I was 18, and I became an addict. I’m still chasing it, and sometimes I go 10 years without it. Sometimes I go four years without it. Sometimes you get it a bunch in a row.

SPACEK: It’s why we do it, for that flow state.

HAWKE: One of the reasons why I took this assignment is obviously, like you, I started young. And like you, I’m from Texas.

SPACEK: Although I’m quite a bit older than you are.

HAWKE: Well, less and less. As each year goes by, we get closer in age.

SPACEK:[Laughs] That’s not true.

HAWKE: I don’t know you. I don’t know what it’s like to be you. I don’t know the inner workings of your life. But you seem to have had a lot of fun. And from the outside, it doesn’t seem to have ruled you. You’ve had your own life. You have, from a distance, a very interesting marriage, a very interesting motherhood. And you seem to have found an equilibrium with the business where you don’t let it own you. And as a person who loves what he does, but also loves his family, I’m trying to figure out how—

SPACEK: And you love your life.

HAWKE: I love my life. I do feel that my work is better when it’s rooted in a real life.

SPACEK: It is. And you continue to live life, so you have things to work with. Material!

HAWKE: Yeah. It’s one of the things that really worries me. I had the thought today: “Wow, Ethan, you’ve got to be careful not to spend too many days doing a press junket because this is not a life.”

SPACEK: This is our payback for that life. I don’t mean this, but we—

HAWKE: It’s a luxury tax.

SPACEK: And it can be very enjoyable, like this.

HAWKE: Well, this is enjoyable. I had this thought while I was watching the new movie. I was sitting there watching you do a scene with Jennifer Lawrence, and I was thinking, “This is fascinating.” Jennifer Lawrence grew up in a very different time, very different place, and I’m watching the two of you do a scene together and you’re both magic. But what could you offer? What is it you could download into a young person’s brain that would help them?

SPACEK: Trust yourself. It’s all inside of you. What acting is, or any art, is exploring the human condition. So every emotion you feel, you can use. I had very little training, except from life. The thing I learned was sense memory, and that’s been everything to me. It’s a simple thing, but I’ve been a one-trick pony.

HAWKE: No you haven’t, because there really is only one trick, and it’s this: know thyself. It’s an [Ralph Waldo] Emerson line, but it’s everything. The thing that’s so misunderstood when people try to talk about method acting is [Konstantin] Stanislavski’s whole thing is that every human being has to build their own method. That is the method. The method is learning—

SPACEK: What works for you.

HAWKE: And to do that, you have to know yourself. To try to build a character, you have to understand what character is. So you have to understand your own character.

SPACEK: And then to be able to be so prepared that you can forget what you’re doing. You can lose yourself in it and become part of the flow.

HAWKE: I do think you’re right, what you were about to say earlier. You can find the flow state in acting.

SPACEK: It’s a beautiful thing.

HAWKE: If I allowed myself, I could be extremely envious of some of your experiences. We’ve already touched on Michael Apted, but 3 Women. I’m super interested in Robert Altman.

SPACEK: Did you ever meet him?

HAWKE: One time when I was really young. I said, “I was born to be in one of your movies.” And he said, “Oh god, I hope not.”

SPACEK: He was a jokester.

HAWKE: What I think he meant was that I was born for better things. He was being self-deprecating and funny.

SPACEK: He changed filmmaking because that was the first time I ever—and anyone ever— wore a battery pack and a microphone, so that actors could just talk whenever they wanted to.

HAWKE: I know. What was exciting about that time?

SPACEK: The ’70s were when independent film really came to fruition.

HAWKE: It was a renaissance.

SPACEK: And the director ruled. Because they were low budget films, the studio left you alone.

HAWKE: And also, people just went to the movies. When I was a kid, you’d ask somebody, “What are you doing this weekend?” They’d say, “I’m going to the movies.” Now they don’t say that. I would go to the movie theater, not to see a specific movie. I was just excited to go to the movies, and I would pick one when I got there.

SPACEK: I would always go to the movies after my date picked me up. He always picked me up at 6:30 and the movie started at 6:00, so we’d get there in about the middle. We’d watch the second half and then stay and watch the beginning to try to figure out what the movie was about. It was this wonderful puzzle, but it’s such a sacrilege to go to see a film in the middle.

HAWKE: Well, it is and it isn’t.

SPACEK: It’s more about the boy I was with.

HAWKE: [Laughs] But that’s okay. I often do that with books. I’ll flip open and start reading from wherever. And if it’s good, I’ll go back to the beginning.

SPACEK: I loved the technicalities of filmmaking, beyond the preparation and figuring out the character. I learned from the directors I worked with, and I appeared at a moment in time where these young filmmakers were looking for somebody that represented the everywoman. I think I stepped into a moment.

HAWKE: And then how was it? You’re playing the ingenue roles, and then you have to step into another moment where you’re not the fresh-faced kid. You’re actually a seasoned professional actor.

SPACEK: Right.

HAWKE: You’ve made all these transitions that get asked of us as performers. We have to face our mortality. A script will read, “Billy, 17. Skateboarding down the street.” And I’ll think for a minute, “That’s my part.”

SPACEK: Isn’t that weird?

HAWKE: And then it goes, “Billy rides in and talks to his father. His father is smoking a joint.” I’m like, “Oh, that’s me.”

SPACEK: [Laughs] It’s an interesting thing, growing old.

HAWKE: And parenting changes you inside. It just does.

SPACEK: It does.

HAWKE: You start to look at the world from a new point of view. Let me ask you this. What percentage of your career was with female directors?

SPACEK: Five percent.

HAWKE: Tiny, right?

SPACEK: One of the clichés was that women were always in a cat fight, which is absurd. Women support each other. The business changes all the time, and you have to adjust. And that’s why I think it’s really good to live a real life because you adjust naturally.

HAWKE: And then you bring that to your work.

SPACEK: I never liked the idea of competing for a role. I just refused to do that. I would screen test or audition, but I always thought whoever got the role, that was their role from the very beginning. We just didn’t know it yet.

HAWKE: Yeah, it’s revealed to us. I remember going into audition rooms, and across from me would be Philip Seymour Hoffman. I’d see Billy Crudup to my left and Liev Schreiber to my right. What you don’t understand as a young person is there’s room for all of us.

SPACEK: There’s room for all of us.

HAWKE: Now those people I’d see in those auditions are the people I love the most. I’m rooting for their careers. When Billy has a triumph, I feel personally connected to it.

SPACEK: Those people you come up with, it’s a bonding experience. And that really changed things for me, the lack of competition. Knowing that whoever got it was the one that deserved it.

HAWKE: And in hindsight, it always feels like that, doesn’t it?

SPACEK: Yeah.

HAWKE: I’ve lost some big parts, but it was so clear that that player was meant to play it. They had ideas for it I was not going to have.

SPACEK: Also, I realized I couldn’t do everything. There was no way I could ever do Shakespeare. It was just outside my wheelhouse. I’ve always appreciated people who were really good at accents. Some accents I can do, but others, this little Texas tongue just couldn’t. Accepting our shortcomings is okay.

HAWKE: It’s okay.

SPACEK: Because we can then focus on what we can do.

HAWKE: Watching Crimes of the Heart was wonderful—all these women loving each other.

SPACEK: We still love each other.

HAWKE: When I saw that, I was on location somewhere and I was sick, so I went to the theater by myself with my box of tissues because I was blowing my nose all the time. But because I was sick, I wept like a small child.

SPACEK: Isn’t it wonderful to cry about someone else’s problems?

HAWKE: It’s so nice. It somehow fills you up.

SPACEK: It really does.

HAWKE: Part of what I was moved by was seeing you all supporting each other. It was contagious. Was that a good experience?

SPACEK: You know what was so wonderful about it? Instead of getting trailers for us, they bought the house right next door to the location where we were filming, and they turned it into dressing rooms.

HAWKE: Great idea.

SPACEK: Jessica [Lange] and I were the only ones with babies, who we’d bring to work, so we shared that in our dressing room. And Diane [Keaton] was there. She had no children yet, so they put her off where she could have a little privacy. What I’ll never forget about Diane is she came into the dressing area where we were all staying, and I had Schuyler who was about four or five years old. She had just gotten a doctor kit, and Diane came in and saw her. She fell to the floor and rolled over on her back and went, “Oh my arm!” Schuyler was looking down at her, and within the next 15 minutes she was covered in candy pills and Band-Aids. I’ll never forget that. I get teary when I think about it. That’s Diane Keaton.

HAWKE: Wow. And when it’s right, it’s easy and fun. And sometimes it’s all wrong and there’s nothing you can do to make it better.

SPACEK: It’s like plowing the backfield.

HAWKE: Yeah.

SPACEK: I always think of it like a train coming through. You see the track and you think, “If I can run along this track and get up to speed and the train comes along and I reach out, the train will take me.” That’s the flow.

HAWKE: Exactly.

SPACEK: Sometimes it takes you; sometimes it flattens you.

HAWKE: You know what I sometimes think? One of the enemies of parenting—a love affair, acting, anything—is too much expectation of a result.

SPACEK: Boy is that true.

HAWKE: I’ve had scenes where the emotion came by accident. If I have a preconceived idea, the cinder blocks go up.

SPACEK: And then you’re trying to get the emotion and you’re not actually in the moment. That’s a trap.

HAWKE: It’s a big trap. I’ve had big moments in my real life where I don’t know if I was emoting at all. I know my heart is breaking, but so often in life, the emotion comes three hours later when you’re driving home.

SPACEK:[Laughs] Yeah!

HAWKE: It’s so corny, but I remember dropping my son off at college. I left the university thinking, “God, everybody always told me how big a deal this is. This is fun! I had a great time.” And I’m driving home and Springsteen’s “Racing in the Street” comes on the radio. I had to pull over because I started sobbing so hard. I was just thinking about my son and I couldn’t stop. I sat by the side of the road for three hours.

SPACEK: I read once that if you’re sobbing in the scene, the audience doesn’t sob. They watch. But if you’re hiding that emotion—you’re holding it at bay, and it’s just there—they sob.

HAWKE: What’s next for you?

SPACEK: I’ve been doing a lot of hard thinking. I know that sounds weird, but I’m at a time in my life where I’m trying to figure out who I am at this age. A happy grandmother. I’ve done some things this year that really were a gift, and I worked with people I really wanted to work with. Michelle Williams, Jennifer Lawrence.

HAWKE: They’re both magic.

SPACEK: I don’t know what I’m going to be doing next work-wise. My gardener quit in the height of the heat dome this summer, so I had to rescue my garden. That was a very grounding thing. I’m doing a self-search now. I just went to a week-long meditation retreat.

HAWKE: That sounds absolutely wonderful to me. And it sounds like you’re taking your own advice, which is to live your life and see what happens. And if you put that as the priority, everything else will take care of itself.

SPACEK: And we’re all home right now, so it’s a real precious time. And we’re getting older, my husband and I. We’re elderly for god’s sake.

HAWKE: You have done the impossible, which is having this unbelievable career in a very bohemian profession, and you’ve had this amazing marriage. You just brought up Jack Fisk, who is—

SPACEK: Something else.

HAWKE: His work on Killers of the Flower Moon was just staggering.

SPACEK: Oh, thank you. And I learned all about the art life from him. The passion.

HAWKE: Where did you guys fall in love?

SPACEK: On Badlands. He was the art director. He was a painter and a sculptor. And everything he does, he does with complete passion. When we were doing Carrie, I got into his research and came across all these biblical etchings, the Gustave [Doré] etchings of the Bible. They were so bizarre. People terrified, lions right on them, probably ate them to nothing. I used that because before that I was just exploring my inner self. But wow, research is great.

HAWKE: It shakes you up. I’m going to have one drink. Do you mind?

SPACEK: No!

HAWKE: And then we’ll finish up.

SPEAKER 4: I was going to say, you fulfilled your obligation with the interview but you’re welcome to stay. It’s up to you. We have plenty of material.

HAWKE: I’m sure you do. She said a lot of brilliant things.

SPACEK: You said a lot of brilliant things.

SPEAKER 4: But I wanted to give you guys the opportunity to chat off the record too, if you want.

HAWKE: Alright, we’ll press pause and now we can feel free to gossip.

SPACEK: Now let’s talk about the good stuff.

———

Hair: Peter Butler using Blu & Green Beauty at Tracey Mattingly.

Makeup: Mariko Arai using Jones Road Beauty at Tracey Mattingly.

Nails: Lolly Koon using Deborah Lippmann at Home Agency.

Set Design: Happy Massee at Lalaland Artists.

Tailor: Macy Idzakovich at The Zaks Team.

Photography Assistants: Milton Arellano and Chris Dinerman.

Fashion Assistant: Brittney Aceves.

Set Design Assistant: Jay Robertson.

Production Director: Alexandra Weiss.

Executive Producer: Georgia Ford.

Studio Manager:Liz Andrien at Pamela Hanson Studio.

Production Intern: Isaac James Levy.

Location: Daylight Studio.