LIT

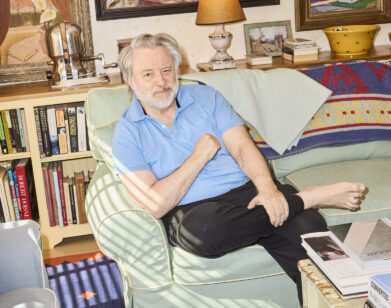

“Catharsis Is For Unsent Emails”: Sloane Crosley, in Conversation With Jay McInerney

In 2019, publishing heavyweight Russell Perreault, who spent 25 years as Vice President and Executive Director of Publicity and Social Media at Vintage Anchor, took his own life, devastating many of the authors whose careers he’d helped spearhead. One of them was Sloane Crosley, whose uproarious 2008 debut I Was Told There’d Be Cake shot her to literary fame. Shortly before Perreault’s suicide, Crosley’s home was burglarized; and shortly after, the world went into lockdown. This triumvirate of unfortunate events provides the scaffolding for her latest book, Grief Is For People, a meditation on loss and suicide that’s often leavened by Crosley’s trademark wit. A few weeks ago, when the author got on the phone with the great Jay McInerney to talk about the book, he wondered if the very act of writing it had helped blunt the terrible sting of loss. “I always feel like hay is for horses, catharsis is for unsent emails and journals,” said Crosley, clever as ever. “I’ve found that writing about my life makes everything just a teeny tiny bit worse instead of better, but it’s worth the sacrifice.” In a wide-ranging conversation, the two discussed how they process suicide, early-career success, and the rapidly changing nature of the New York publishing landscape.

———

SLOANE CROSLEY: How are you feeling?

JAY MCINERNEY: I’m better. It was six weeks ago that I bashed my head in the middle of the night. I stood up too quickly.

CROSLEY: Oh, this happens to my boyfriend constantly.

MCINERNEY: This time I hit something sharp in my bedroom. When I became conscious, the entire apartment was covered in blood. It looked like I’d murdered someone.

CROSLEY: I was about to say, “Who am I talking to? You or Bret Easton Ellis?”

MCINERNEY: I’m bouncing back. I loved reading your book, even though it was a somewhat challenging and provocative experience, not least because I’ve experienced this myself.

CROSLEY: I know you have.

MCINERNEY: Which you allude to, in fact. I lived with Jeanine Pepler for several years and she was probably my closest friend at the time of her death. You mentioned her suicide as being yet another rocking of your world, but what was entirely different for me was that Jeanine suffered from manic depression. She had suicidal ideation, which we spoke about many times, so when she killed herself, at least I didn’t have to sit back and say, “What the hell? How could this be? What happened?”

CROSLEY: Right. You’re not going through the rolodex of images.

MCINERNEY: I’d already taken her to the hospital twice with slit wrists and overdoses. Curiously, this was also one of those rules of three. You mentioned there was Tony Bourdain and–

CROSLEY: Kate Spade was the month before.

MCINERNEY: This was all in very rapid succession. I used to get angry at people when they would say, “Why? Why? Why?” [Because] it’s an illness. What I found extraordinary about this book was that I assume you’re not telling us everything that you know, yet it seems like an utter mystery why Russell kills himself.

CROSLEY: I’m not saying absolutely every detail I possibly could. He has a mother, a partner, a nephew, a sister, so there’s a couple of common-sense protective things, but yes, we all felt the shock of it. It doesn’t make it better or worse if you “see it coming,” as you did with Jeanine. You can mix your food or separate it, it’s all going to the same place no matter what. People go on a fact-finding mission to find out if I knew more. It puts the strange onus on the person in grief because I know that they want to upcycle Russell’s tragedy to scan their own loved ones. I barely get out of bed in the morning and I’m crying until my jaw hurts, so I can’t help you. Part of what I wrote in the book—and it’s a shocking part of the book—is that the question people should be asking is not why it’s such a stigma, but why more people don’t do this? Life is so difficult. And it sounds extremely morbid, but it’s a conscious choice to not look at this option. But Russell looked at it.

MCINERNEY: Well, clearly he did, and yet nobody seems to have seen it coming in any way. Do you feel like that’s true?

CROSLEY: I do. He was so sarcastic and he joked about it the way everyone does. He said, “I’d rather kill myself than go to that party.” Did I think he was happy? No, not particularly.

MCINERNEY: Well, he seems like a perfectionist and somewhat cynical. He’s certainly not someone who’s skipping through the pansies every day. Do you think he felt that his world, the professional world he’d grown up in, was shrinking and changing in a way that made him extremely unhappy?

CROSLEY: Yes. It’s also age, right? There’s something about that age where you feel trapped and entrenched in your life. You’ve gone so far down a road that you don’t really see other options. I remember being 24 and thinking I was too old to move to Paris or London and I should’ve done it when I was 20. Do you know what I mean?

MCINERNEY: Yeah.

CROSLEY: If you’re really suffering, that becomes weighty and dark. He had worked for Vintage for so long. He loved books, not in the cheesy way, but in the way that he was pushing good ones forth into the world. I do think he felt this sort of narrowing. But part of the point of my book is that you can spin around in circles with speculation no matter what and it’s not going to fix it. If I could go back and rip this friendship out at the root, pretend I never knew him, then maybe it wouldn’t hurt.

MCINERNEY: Early on in the book, you say, “Am I making the friendship bigger than it was to keep it from getting any smaller?” Do you still feel like Russell was your best friend?

CROSLEY: I do. I feel like he was my dearest friend, which is slightly different than best. I took for granted that he was this stalwart figure within the publishing world. I took for granted that it would not be affected by the world around him. In the past year, after I quit Vintage, you really had to hound him to stay friends.

MCINERNEY: Early in the book, you talk about all the time you spent up in Connecticut at his house and all the nights you slept there. But Russell basically closed the doors almost 15 years before he died. He suddenly stopped inviting others, and especially you, up to Connecticut. That seems like a second parting, in a way.

CROSLEY: Yes. There was definitely some separation. We still saw each other in the city and communicated a lot, but I try to be as careful as I can in the book about conjecture. I try not to speak too much about why the invitations came to a slow trickle and then stopped.

MCINERNEY: Did you ever ask yourself whether it was too much of an invasion of privacy to write this book? It’s fascinating that within a month of his suicide, you’re writing about it.

CROSLEY: Yes. I knew I would write about it. Did I know I was going to write what ended up being a bit of a biography of him and a bit of a memoir from me? I don’t think so. I didn’t even know it was going to be a full-length book. I had already started writing about the burglary that kicks off the book.

MCINERNEY: I haven’t even mentioned that yet.

CROSLEY: Then Russell, obviously, poured gasoline on that fire and replaced it with a much bigger fire. I thought, “This is a little bit bigger than a couple of essays.”

MCINERNEY: Then there was the third loss that you suffered. You had the burglary, you had the suicide, which is the worst, but then the pandemic struck, which you call a “global catastrophe,” and quite rightly.

CROSLEY: It’s like these concentric circles.

MCINERNEY: Just to remind people that you’re a great humorist, one of the things you write is, “We were not depressed all the time, sometimes we were drunk.”

CROSLEY: I feel like there’s this sweet spot that you just eventually have to close your eyes and feel around for where Capote said something like, “You should only write when your tears are dry.” And sometimes I think maybe the tissues should be wet, you know what I mean? I don’t think I could write this now, and I’m sure you couldn’t write a post 9/11 book now. People are exhausted by it instantly, so with the pandemic section, I was a little bit nervous because I thought there’s no one on god’s green earth who wants to hear about hand sanitizer anymore.

MCINERNEY: Then you have this weird thing that opens the book. All of your jewelry from your grandmother is stolen in a tawdry New York City residential robbery, which, as you said, hearkens back to the seventies.

CROSLEY: Tawdry is such a great word for it.

MCINERNEY: It reminds me of when I first came to New York and everybody was the victim of those kinds of robbery.

CROSLEY: The whole thing has this old-fashioned New York vibe that’s very unintentional. I’m like, “Can I just have some graffiti on the subway? Why do I have to get robbed?”

MCINERNEY: You’re the only person I know who’s actually tried to track down their stolen property.

CROSLEY: Jay, I work freelance, I have a lot of time on my hands. I will hunt you down and I will find you like the movie Taken. I don’t want to spoil it, but I did track down a couple of the culprits.

MCINERNEY: The scenes in the jewelry district are quite good.

CROSLEY: What’s strange about it is when my editor was editing it he said, “Can you insert some emotion into some of these scenes? Wouldn’t you be scared to march into the Diamond District and start shaking people down?” Now when I say that out loud, I agree with him, but it might be the one lie of the book. I felt almost no fear, but I don’t think that’s something to be commended. It’s only because Russell had died and I just needed to stop the bleed of loss.

MCINERNEY: It was pretty ballsy and clearly sort of helped you deal with Russell’s death. You say at one point, “I want people feeling sorry for me about the jewelry as much as I do not want them feeling sorry for me about Russell.”

CROSLEY: The robbery happened to me and the suicide did not happen to me. In the city, there’s such a gravitational pull towards being at the center of upset. I had that allergy from the start. I remember there were pizza boxes after 9/11 that were like, “Never forget.”

MCINERNEY: You make fun of that syndrome as well. Most of us who live in New York think that anything important happens here. And if it doesn’t happen here, it’s not important.

CROSLEY: I know. Part of the book is trying to parse out what is real, what is one’s own nostalgia. You even have that for books themselves. I wanted to ask you one question, but I don’t know if it’s an annoying, controversial question.

MCINERNEY: Please, feel free.

CROSLEY: Oh, goody. There’s no question I can ask you that you haven’t been asked, but as someone who had a massive early success that continues on in a thousand ways, do you feel the tentacles reach out across format and impact–

MCINERNEY: Yeah.

CROSLEY: Wait, do you know what I’m going to say?

MCINERNEY: Strangely enough, I got an email from a college student asking that exact question yesterday.

CROSLEY: I’m asking college questions. Oh, my god.

MCINERNEY: No, no. When I first published Bright Lights, Big City and it just kept reverberating out into the culture, I couldn’t believe my luck. All doors were open to me and I could meet anybody I wanted. If I’d only known at the time I could do anything I wanted. At first, it was the dream come true and it was the best thing that ever happened to me, and then eventually, there came a point about seven or eight years in when I just thought, “Jesus.” When people said, “Oh, I loved your book,” I thought, “Well, in the meantime, I’ve published three more. What about those?”

CROSLEY: Do you ever snidely do the thing where you’re like, “Which one?”

MCINERNEY: Oh, yeah. I don’t do that anymore because I realized I was really lucky to have this book, to have it reach out into the world the way it did. But there was a point where I really resented it. There came a point where I just didn’t want to play “Free Bird” again, I didn’t want to play “Stairway To Heaven.” But I got over it and now I just feel lucky. I’m about to publish my eighth novel. I feel like Bright Lights gave me a career, so I’m over it.

CROSLEY: When I describe the publishing world, do you feel that’s narrowed for you at all? I feel like you’re someone who is so in demand.

MCINERNEY: What happened to me in the early 1980s and subsequently to people like Bret Easton Ellis and Tama Janowitz, the way that we became central to the conversation and the culture, I’m not sure that can happen anymore with a literary novel. I’m scared about my next novel. I’m not a very fashionable category of writer at this moment. I’m not dead, but I am a white male.

CROSLEY: The truth is that you still have an audience.

MCINERNEY: I hope so. I have something I wanted to say. I’ve known you for years, but I most recently saw you, again, at a literary festival in Gstaad, Switzerland and we spent a bunch of time together and talked about what we were working on. You told me about this book and I thought, “Is she crazy?”

CROSLEY: Wait, why?

MCINERNEY: Well, because I thought, “Here’s a renowned humorist writing about suicide.” I thought, “That’s going to be one weird book.” I have to say that it’s a very unusual book, but I really loved it and I’m very glad I was able to read it. I actually read it twice. You pulled it off.

CROSLEY: First of all, thank you. I would say that the books I like the best, the texture of those books comes from a dark subject in an unexpected tone, or a light subject with a dark tone. I don’t know if you ever read Miriam Toews’ All My Puny Sorrows.

MCINERNEY: Yeah.

CROSLEY: Or The Wicked Pavilion by Dawn Powell, which is more about a scheme than a suicide.

MCINERNEY: A lot of people think Bright Lights, Big City is a tragedy, some people think it’s a comedy, and I guess the truth is somewhere in between.

CROSLEY: You’re writing about the pandemic right now?

MCINERNEY: This book starts in the Pandemic. I’m happy to say that it finishes elsewhere. Thank god we came out of it so we could all start to forget it. People are probably sick of it. You skirted it, but there were times when one thinks, “Oh, shit. Not only did her best friend kill himself, but it’s lockdown now.”

CROSLEY: It’s lockdown, but it’s lockdown with your emotions. When I saw you in Switzerland, I was so happy. First, because I like you, but also I thought, “Oh, this is a really good opportunity to tell him that Jeanine is in the book.

MCINERNEY: I was happy to see that part. It’s one of the worst things that ever happened to me, but I don’t want it to be forgotten. Do you feel like you’ve gone through several stages [of grief] now, and was the book part of going through those stages?

CROSLEY: You’re asking about catharsis. I always feel like hay is for horses, catharsis is for unsent emails and journals. I’ve found that writing about my life makes everything just a teeny tiny bit worse instead of better, but it’s worth the sacrifice. I know that sounds dark. But there’s this assumption that you must feel so much better after writing about it.

MCINERNEY: That’s what they always tell you.

CROSLEY: I do feel more of a whole person these days, so that’s good. It’s supposed to be funny, and you’re supposed to feel terrible as you laugh about it.

MCINERNEY: In a Shakespeare class, you would almost call the jewelry robbery a comic relief. And your horrible grandmother.

CROSLEY: Once I decided that the focus was going to be about not even about his suicide, really, but about this person who I watched fit in less and less with the world that he built, then you can casually mention my abusive grandmother without it being really distracting. It becomes a bullet point.

MCINERNEY: This is sort of a minor footnote, but at one point you say that he loved the book Edie, which was the oral history of Edie Sedgwick compiled by George Plimpton and Jean Stein. I was wondering if you meant that he was kind of entranced by the glamor of suicide. Edie died of a drug overdose, which may or may not be suicide.

CROSLEY: Jean Stein jumped out a window.

MCINERNEY: Yes, that’s right.

CROSLEY: I say it was sort of obliquely connected to his death because he loved being around famous authors and people. He liked to know the best bakery, the correct place to go, the best pen. Edie is a world full of people who were born into knowing what was the best of everything. He had to work a little harder for it because he was not born into a world like that, so he fetishized it. When some of the glamor and the sheen of publishing was wearing off, when it just became clear that certain avenues were not available to you anymore, it really hurts. He just loved Edie because it was full of insane and fabulous people. I don’t think, weirdly, the outcome for Edie herself had anything to do with it. It’s almost coincidental that she died by suicide.

MCINERNEY: Right.

CROSLEY: He loved that book. Man, when I think about the books that are indelible, like John Williams’ Stoner, he loved that book too. I can still name the people that Russell not only tended to, but helped make famous. He got Haywire by Brooke Hayward back into print. He was such an advocate for those things. Think about what they are, though. Haywire’s about an extremely glamorous child.

MCINERNEY: Privilege and Hollywood aristocracy.

CROSLEY: Russell could see through the trappings of it to the tragedy. Anyway, I’m so happy you liked the book. It means a lot that you read it, and that you read it twice.

MCINERNEY: It’s a very unlikely book to like, and yet one does.

CROSLEY: Remind me not to ask you for any blurbs.