NOM NOM

Slutty Cheff Tells Lena Dunham How She Went From Shitposter to Bestseller

Slutty Cheff knows what she wants and she’s not afraid to write about it. It started with Instagram, where she rose to fame skewering London’s gastronomic boys’ club one arousing caption at a time. Now, with her memoir Tart: Misadventures of an Anonymous Chef, she’s serving something richer: a deliriously honest, wickedly horny, and sharply observed account of abandoning a soul-crushing nine-to-five for the sweltering chaos of London’s high-end kitchens. It’s a meditation on excess: emotional, erotic, and edible. Naturally, Lena Dunham, Londoner and patron saint of oversharers, devoured the book (and the three-course meal Slutty prepared for her when they caught up earlier this summer). In a conversation that spans burnout, orgasms, and what it’s like to be the only woman in the kitchen, the two dig into pleasure, shame, and why sluttiness might just be the purest form of self-love. As Cheff writes: “I like too much, and I always have.”—OLAMIDE OYENUSI

———

LENA DUNHAM: Hello, Slutty. You’re my friend, but I’m not going to use your real name. I’m going to call you by the name that I keep you as in my phone, which is “Slutty.” And I just have to say how fun it is to have a friend who’s saved in your phone as “Slutty,” and for people to look over and see texts come up as “Slutty.”

SLUTTY CHEFF: I’m so happy that you enjoy it, but some people shouldn’t, like my male cousin who I see all the time. I’ll go meet him and his friends at the pub and he’ll introduce me as Slutty. I’m like, “You can’t be doing that.”

LENA DUNHAM: But I’m allowed to do it because you know that I’ve reclaimed the word.

SLUTTY CHEFF: Or a family barbecue with my 80-year-old great-aunt who’ll be like, “Oh, pass Slutty the ketchup.”

DUNHAM: [Laughs] So this book is obviously very much about your relationship to your other career, but it’s also about a lot of stuff. It’s about ego, it’s about growing up, it’s about sex. It’s about figuring out who you are. When was the moment you started to write, and the moment you started to think of yourself as a writer?

CHEFF: I feel like I still haven’t started to write. And when people use the word “writer,” that feels like such a fancy and esteemed job, like one of those dream jobs that very few people get, so I still find that hard. But in terms of writing, I kept diaries my whole life just writing about boys or hating my mom since I was 10 or something. That was when I started to have an interest in writing. But when it came to school, I didn’t really have any interest. I didn’t go to university, so I’ve never studied writing. Then I started this Instagram thing, and the validation really gave me the confidence to pursue it. That’s what’s nice about Instagram—you see people’s reaction in live time and it’s very validating and encouraging. So I just kept going, started pitching magazines, and then this happened.

DUNHAM: It’s interesting, because so many people think about social media as exclusively a place for people to show off their outfits and try to make other people jealous. But you did something that I find really compelling, which is you were able to use the captions base as a place to basically start test-driving these mini essays. You were working in kitchens all over London. We won’t name the kitchens, but it was some very high-level restaurants. I think people might have initially misperceived it as, “She’s pulling back the curtain on kitchens” or “she’s really telling it like it is about the misogyny of the food industry,” and all of that was true. But it was a place for you to start to tell your story. What inspired the anonymous Instagram account? Was it a creative choice or just, “I do not want these fucking people to know who I am”?

CHEFF: I didn’t have Instagram for four or five years in my late teens and early 20s because of my first heartbreak. I deleted all social media because I literally couldn’t handle seeing my ex at parties or with other girls or whatever. So I deleted—

DUNHAM: Relatable. I think I’ve told you that the first time I deleted social media was because the chef I was in love with kept posting pictures of another hostess from the restaurant. She’d be like, eating a giant piece of naan or walking around the botanical center and I was like, “I cannot take this.” So if anyone wants to know why I don’t have Facebook, it’s ’cause a chef broke my heart.

CHEFF: Yeah, it’s this thing where loads of people have this thing where, when they break up with a boy, they obsessively look at their stories or they obsessively still have them on Find My Friends or see what they’re watching on Netflix with their new girlfriend or whatever. And for me, the heartbreak was so bad. If I saw something like that, it would ruin my whole fucking day, so I just wanted to get rid of social media. And then four years later, I kind of missed it ’cause everyone was talking about Kim Kardashian’s BBL and I don’t know, all this meme stuff and pop culture.

DUNHAM: You were like, “I’ve got to find out if it’s a BBL.”

CHEFF: Exactly. But I still wanted to stay removed from that thing of observing other people and looking at their life and seeing what they’re doing, because even though I feel quite happy with where my life is right now, I can still bum out by looking at other people’s stuff. So I literally just created an anonymous account for fun, so I could look at memes and stuff. I was really into cooking at the time so I uploaded random pictures just to fill the grid. I was with my dad, we had a leftover steak sandwich, and I took a picture and I uploaded it as “leftover beef sandwich #roastqueefsandwich.” And then I was like, “Oh, this is great: food and sex. Maybe I’ll fucking go viral and get some free stuff.” And then I became more and more obsessed with cooking in restaurants and stuff, so I started going to restaurants and there were these amazing stereotypical characters. I really loved writing and it got more personal. I think the reason that people box me into that whole campaign of “feminist trying to switch up the industry” is because the moment that I went viral, I suppose, was when I was talking about the gender and race dynamics in kitchens. I wrote a sort of tongue-in-cheek post about that ended up going viral. Then I wrote my first ever Vogue piece on that and the whole Chef Daddy movement. But I have that imposter syndrome thing of, “there are millions of people that have spent way more time in kitchens than me,” so I didn’t feel capable of taking on that role.

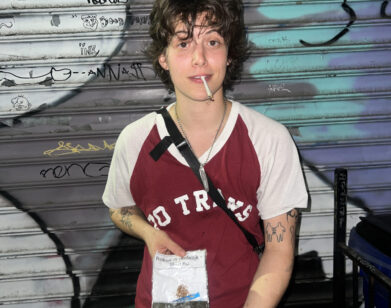

DUNHAM: I became familiar with you shortly before your book proposal came out, when your Instagram was becoming a real talking point in London. I remember looking at this picture of you where you’re in a bra wearing a hamburger mask—

CHEFF: I don’t know if it was a bra…

DUNHAM: You were wearing something that felt a little bit—

CHEFF: Sexy.

DUNHAM: I put you in a bra in my mind. That’s how much of a creep I am.

CHEFF: I think I know the one you’re talking about. It’s this tight red Adidas thing.

DUNHAM: Yeah, and you looked amazing. And the hamburger mask somehow only made it sexier.

CHEFF: Thank you.

DUNHAM: There were people going, “I know who she is.” And by the way, three different people have said they knew who you were and they were wrong.

CHEFF: I love that.

DUNHAM: So I feel really delighted that it became such a conversation. Do you remember the moment that you realized that trying to uncover your identity was starting to become a talking point? I think of you as Hannah Montana: pop star by night, high school girl by day. When was the moment you realized people were really trying to figure out who you were and that, as a result, this was a bit of a sensation?

CHEFF: It was fucking nauseating because I was working 50 hours in the kitchen, so I didn’t really take note of much. I was just writing Instagram captions on the bus home and posting them, and then my phone would be in my pocket or in my locker at work for 10 hours. I did not know what was going on. But when I wrote my first ever Vogue piece, which was all about what it’s like to be a girl in the kitchen and why this Chef Daddy thing is a bit lame. I blocked all the chefs that I worked with on Instagram. I love them all, they’re great guys, but I didn’t want them reading about me having sex and getting fingered. And then I came in one day and one of the chefs nudged me and he was like, “Oh, nice piece by the way.” And I was like, “Fuck this.”

DUNHAM: Oh my gosh. Did you try to pretend it wasn’t you?

CHEFF: I was like, “What?” ‘Cause I thought this blocking thing was foolproof. So then I was going into service being like, “What have I done? I don’t want to work in this kitchen. I’m going to quit tomorrow. This is so awkward.” And then halfway through service, the marketing girl at the restaurant came down and she was like, “I think we need to have a chat after seeing what you wrote” or something. And I took her straight into the fucking changing room and I was like, “Do not speak about this in front of these boys.” But she was like, “Oh, we would love to have you write something…” I was like, “No, no, no,” because the anonymity to me is fucking really sacred. I know people know who I am or where I worked or whatever, but they’re just chefs. They don’t give enough of a fuck to out me or whatever.

DUNHAM: People had told me the wrong person so much that when you walked into our first meeting, I was ready for someone so different. You’re chic, but I was expecting someone who had much more of a cunty blonde bob attitude.

CHEFF: Oh my god, I was so fucking dead that day. I had worked 16 hours the day before.

DUNHAM: For the audience that doesn’t understand, I was fighting for my life to option Slutty’s book.

CHEFF: That was the fucking craziest experience of my life. Literally two days before my book goes to bid, I’m in the area with my dad because we’re like, “Oh, what’s going to happen?” We go to the book agent and he’s like, “This is blowing up. We’ve got 11 bids for your book.” I was like, “What the fuck is going on?” My dad was already crying. And then he was like, “By the way, I also want to tell you about someone that you really admire who’s into your book,” and he said your name. And me and my dad just fucking broke down in this small little corporate office.

DUNHAM: That’s so tender. I feel like a misperception about what you’re writing is that you’re trying to sort of expose the misogyny of the food industry from the inside. And yes, you are, but that’s actually in some way pigeonholing what you do. You are exposing the misogyny, but in the process of telling your own first-person story. You’re not trying to be a whistleblower; you’re trying to be a truth-teller.

CHEFF: I remember I was talking to Marina [O’Laughlin], who’s a food columnist at The Financial Times. She said the same thing: “Male writers don’t have to have this angle on their writing. They don’t get boxed in like this.” And then when I went for a couple book meetings, they were like, “This is going to be a book all about exposing how to change the industry.” But I’m conflicted because, obviously, I don’t love the deeply dark things that do happen, but I worked with some men that were really, really supportive and they’re still my very, very close friends. So for me to go on this path to disrupt and change an industry, it’s overwhelming and I don’t feel equipped. Of course I have interest in changing the industry, but I think it’s unfair to put that burden on someone because they cover it in their writing.

DUNHAM: You are trying to share your own perspective of this world that was seductive to you, and then you were equally seduced while also seeing everything that was maddening about it. But to reduce your writing blowing the whistle on misogyny in the food industry is to take away what is incredibly personal about it. I know it’s still hard for you to think of yourself as a writer, but I have news for you: bitch, you are. You wrote a book and now you’re going to write a TV show and I can tell the people here that you are a natural-born TV writer.

CHEFF: Oh, thank you.

DUNHAM: When you were first seduced by the food industry, what is it that you saw that you wanted? And then once you actually found yourself in the kitchen you’d dreamed of being in, what did you love about it and what was different than you had dreamed?

CHEFF: Initially, I think I was seduced by the industry because I’d worked straight from school in a sort of office-y environment for a good few years. I’d slipped into this job, and I kind of had this really low point where I became really depressed and started having panic attacks. I kind of recovered from that by cooking. Then I got more into restaurants and the food that was available in my city. I observed the cultures around it. I was seduced by the idea that these people were working so hard for something so simple, which is food, and that’s such a cool thing to do on such unrelenting hours. It’s like a rock star or a musician, people can work for fucking decades making music, doing everything they can, and they’ll continue to do it whether or not they make it because they’re so into it. I thought that was really cool. And I just needed that moment ’cause I felt like my 20s were going so quickly and I was bumming out. So I was like, “Fuck it, I need to explore something different and connect with people that are a bit more carefree, I suppose.” But then when I went into kitchens, I found this whole other depth. The characters, the way that you can get two chefs in the same kitchen with polar opposite politics and completely different personalities, gender, race, class, whatever. Over service, everything dissipates and they’re just laughing or working together and it’s this really amazing, unifying thing. And then there was this sexy element as well. I think that came to me because I was coming out of this low time and I was wanting to date and get laid again.

DUNHAM: Do you feel like your love of food has persisted?

CHEFF: Absolutely. As I said in my text to you before we got on this call, I’ve just had an argument with my dad about the tadka dal, because I’m so stressed about him eating more than his share of the food that we got last night. So I laid it all out before we had our call and I was like, “This is yours, and this is mine.” I’ve been thinking about this Indian dish all day. I am completely besotted by food and I always will be on a basic human greed level. When I get really drunk and sentimental with my friends I’ll be like, “How amazing that love and sex exists in the world.” And food is the same thing. Imagine if humans just needed water to survive and food didn’t exist. How lame would that be?

DUNHAM: It would be the lamest thing in the world. I went over to your house once and you were like, “Oh, I’m making the most simple meal.” And you made a three-course pasta dinner. And I felt love. I felt god. I was sitting there like, “This is what it feels like to be cared for by another person.”

CHEFF: I was like, “Oh my fucking god, Lena Dunham’s coming to my flat to talk about my writing.” I’m like, “What the fuck am I going to cook?” And that whole journey was so thrilling. We ended up having this amazing human moment, sharing food, and me giving you a special jelly ice grape thing from the freezer and you being like, “Fuck, I’ve never had this.”

DUNHAM: Oh my god, it was so delicious.

CHEFF: Maybe that’s why I’m so obsessed with cooking, because you don’t need to have some crazy knowledge of something to be into it. Food has its own culture that’s equally as chic, sexy and fashionable as art, film, cinema, fashion, but everybody can be into it. All you have to do is go to the shop and get some food.

DUNHAM: What I also wanted to talk about is how female memoirs are considered to be this kind of navel-gazing, self-important, glorified diary, while male memoirs are celebrated as honesty and bravery.

CHEFF: Yeah. “Self-pitying.”

DUNHAM: And I love that at the core, you’re talking about the confusion, the complexity, both the horniness and self-hatred and panic of being a young woman. But at the same time, you have this love, which is food, which is an inherently generous love. Your work can be petty and it can be angry, but at the core of it is this desire to make things that make other people happy. And I find that to be a really interesting tension. I assume that being a chef and being in kitchens had kind of become your identity. What was it like when that identity had to change in order to get this book into the world?

CHEFF: It was really, really anxiety-inducing. I’m still thinking about that every day, especially because my boyfriend is working back-to-back doubles. When you’ve worked that hard in a physical job, it feels phony to be making more money doing something where you can sit down and dream. And that is the biggest provision—I feel really like I have to justify it to everyone I speak to. I’m still in touch with all these chefs and hearing about their service and I just feel like I graduated too early. People ask, “Are you going to go back to kitchens?” I don’t want to leave hospitality forever, but it’s such an all-consuming job.

DUNHAM: It’s being a part-time emergency room doctor. You’re either doing it or you’re not doing it.

CHEFF: Yeah, like you’re halfway through fucking giving someone… What’s it called?

DUNHAM: CPR?

CHEFF: Yeah, CPR, or the kiss of life.

DUNHAM: You know we’re in the right place because we don’t know what CPR is called.

CHEFF: [Laughs] Yeah, yeah, yeah, exactly.

DUNHAM: When I’m writing, there’s always certain people who I’m reaching toward as my North Star. Who are the writers who had that North Star quality for you?

CHEFF: I’ll just get the obvious one out the way and say you.

DUNHAM: Oh, that’s very tender.

CHEFF: And then I had this phase where I was really wanting to read loads of classic books so I could name-drop stuff, because I never read when I was a late teenager. Which is lame, I shouldn’t have felt like that. But I did, so I tried to read all this classic stuff, big hefty titles of old men who were perverts. Henry Miller has this trilogy about sex, and I think one of them was banned in Europe or something.

DUNHAM: Henry Miller’s amazing, but it’s also amazing to realize that those are banned and now we have 8,000 mainstream erotica pieces.

CHEFF: [Laughs] I read this line that was comparing pussy juice to warm soup and it was so visceral and gross. And then there was Money by Martin Amis, and then there was Bright Lights, Big City by Jay McInerney and Woman by Charles Buwosky. They were these men writing about alcoholism or depression or sex in such visceral, unrelenting, ugly ways, but with zero shame. But it wasn’t me reading men because I was sexist. I was interested in the prospect of developing my own writing. I’ve grown up with women swearing and referencing sex and being powerful. All the women in my family earn more money and are more functional than the men in my family, whether it be my aunt, my grandma, my great aunt, whatever. And I found that kind of arrogance to bear all cool.

DUNHAM: But it’s interesting how those books were important to me before I discovered all of the women who were doing the same thing because those are the books that have been mainstreamed. But what I find so compelling is in those books, they might be comparing pussy juice to warm soup, but the women might as well be tables or cups. Then, when I read women who are writing about sex, whether it’s Melissa Febos or Miranda July, the characters who they’re engaging with are just as fully realized as they are.

CHEFF: Absolutely.

DUNHAM: And it has to do with women being forced to see men as three-dimensional, because we have to survive. But those men, especially at the time they were writing, were never forced to see women as three-dimensional.

CHEFF: Yeah, like when you think about the female characters that they describe, all you can remember is the size of their tits or the color of their hair, because they wouldn’t even bother going beyond that.

DUNHAM: What is your relationship to food writing?

CHEFF: I’m really quite ashamed to say that I have very little interest in it. I got into food late and I didn’t want to read about food. I wanted to make food. It feels like having a wank instead of having sex, you know what I mean?

DUNHAM: Yes, I do. How do you feel about your relationship with writing now going forward? Do you feel like there are things that you want to say that have nothing to do with your time in the kitchen? Where are you imagining your pen wandering now?

CHEFF: I basically want to write forever. I want this to be my job. I love it more than anything in the world. I feel like the most authentic me. We’re working on this TV show, and that’s obviously going to be revolving around food.

DUNHAM: It’s about food, but it’s also about ambition and it’s about trying to figure out where you belong. The scenes where you’re in the kitchen with men remind me of when I was trying to figure out, “Is there a way for me to be a filmmaker that doesn’t involve me being in an environment of rough and gruff men treating cinema like it’s war? Is there a way for me to do this that’s mine?” And that’s something I connect so deeply with in the story. Often, as women, the place where we find ourselves is where we can make a dent in an environment that’s quote-unquote “traditionally patriarchal.” I spent a lot of time in my early 20s as the one girl on a film set and thinking, “Is there something to this?” And it turned out I wanted to create different kinds of film sets where I was surrounded by women, where I was surrounded by people who weren’t just cis white dudes flexing their muscles, and I’ve gotten to do that. For the most part, I eat like a three-and-a-half year old. But for me, I understand this book because it’s also deeply about ambition.

CHEFF: Yeah. And I do want to move beyond this. I love the idea of writing outside of the kitchen stuff and the “Slutty Cheff” stuff but I don’t know what that would look like. I have endless dreams about where the writing will go, but nothing is tangible or realized.

DUNHAM: You may just end up being like Nora Ephron, one of those writers who just happened to be really good at cooking.

CHEFF: Yeah, Heartburn is one of my favorite books, of course. I don’t know where it’ll go. Right now, I’m so amazed that this book is doing well and that it became a Sunday Times Bestseller. I’m kind of like, “Oh, fuck, shall I just drop the mic and just go back to the kitchens? Because it can’t get better than this.” But I’m just too obsessed with telling stories.

DUNHAM: Guess what? I think that’s a beautiful place for us to close.

CHEFF: Fuck yeah.