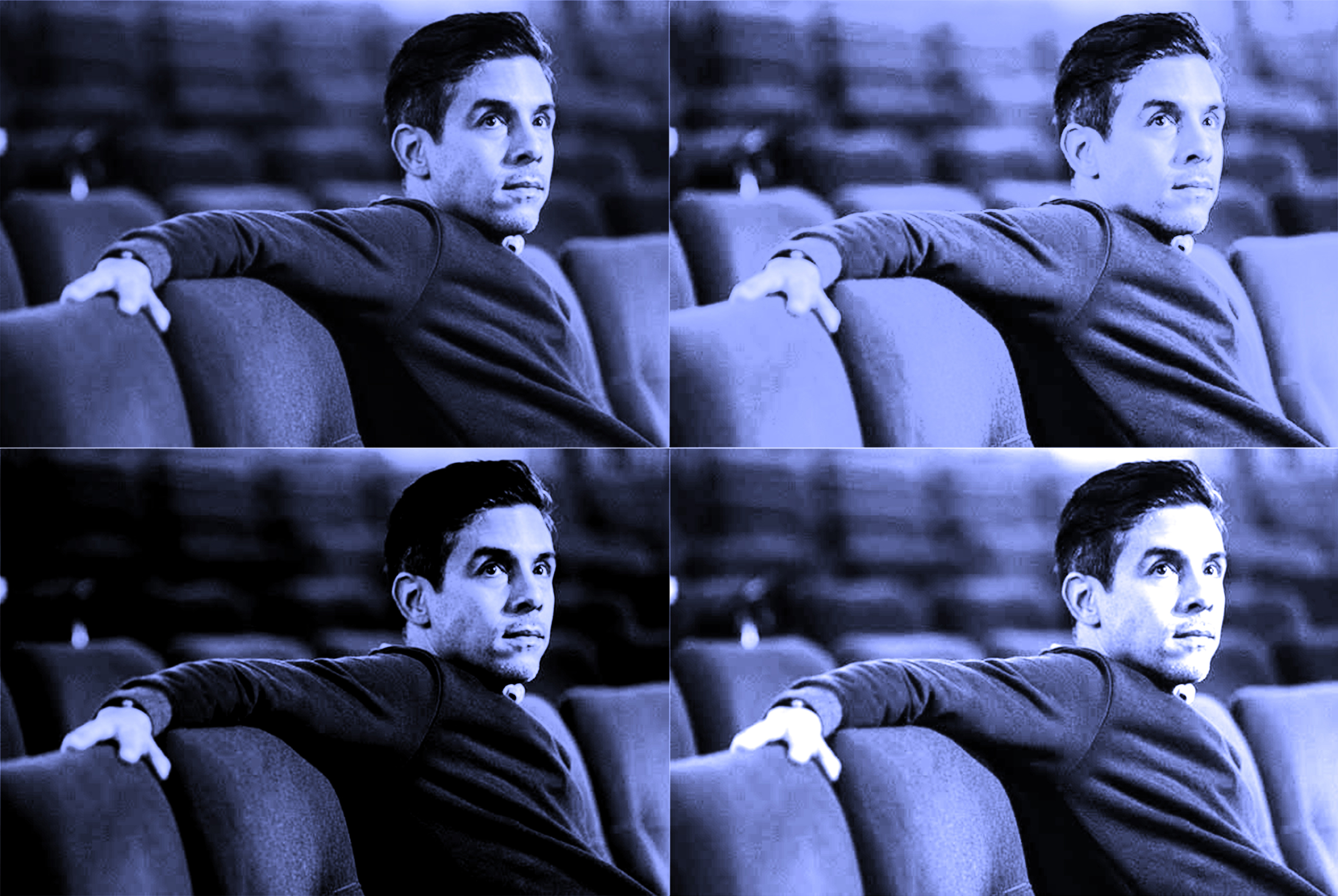

Playwright Matthew Lopez Wants to Hear Your Stories

Photo by Matthew Murphy, Art by Mark Burger.

Though The Inheritance is his fifth play, Matthew Lopez has remained relatively unknown to the general public. That’s about to change, with the two-part, six-and-a-half-hour meditation on the gay generation gap, AIDS, politics, and the therapeutic properties of storytelling itself hitting the Broadway stage November 14. The generally ambitious, often funny, occasionally heartbreaking, and always engaging production has garnered unavoidable comparisons to the Broadway play Angels in America, Tony Kushner’s two-part, six-and-a-half-hour meditation on the gay generation gap, AIDS, politics, and the therapeutic properties of storytelling itself. (Albeit without Kushner’s enraged urgency, multi-targeted satire, and excoriating expositions.) But as Lopez asserts, the comparisons are surface-level, at best.

The Inheritance follows a group of thirty-something gay men in New York City and on Fire Island as they wrestle with aging, relationships, careers, financial hardships, cementing legacies, and the great debt they owe to their forebearers, those who were confined to closets and experienced firsthand the horrors of the AIDS crisis. I sat down with Lopez at the Ethel Barrymore Theater between a matinee and evening performance of the show. The playwright spoke about making friends with audience members, giving people the room to tell their own stories, and B-12 shots.

———

BRIAN ALESSANDRO: I attended the first night preview of both Part I on September 27th and Part II on October 11th. There was a palpable sense of community and empathy in the audience during intermissions. Strangers were comforting one another. Have you found that to be the case?

MATTHEW LOPEZ: Yeah, it was particularly acute in London at the Young Vic. They sold tickets for both parts for one day, so you were in the same seat with the same seat mates beside you all day long, for six and half hours. I know of friendships that have formed. Strangers have had dinner together. So, yeah, this play does draw people together. In some cases, even between us and the audience. Especially in the Young Vic, when you come out of the theater, there’s the bar, so you have drinks with audience members. And you find that people really want to tell you their stories. What I learned really early on is after asking audience members to sit through six-and-a-half hours of this play, my job now is to sit and listen to their stories. And they all have so many amazing stories to tell.

ALESSANDRO: Have any of these relationships with audience members endured, six months later, a year later?

LOPEZ: Yeah, I have made friends with people who have seen the play in London. The actors and director and I became a family, and then the family grew to include the audience.

ALESSANDRO: What kind of feedback have you received from the audience?

LOPEZ: A lot of people want to tell me their stories, and it’s not just the people who were alive back then. Though the play deals with AIDS, it’s about more than just the epidemic. It deals with things that plague gay men now. It’s very much about addiction, too. And the audience’s experiences run the gamut. And these audiences feel emboldened in the best way possible to not keep secrets. And they feel like they trust us enough to tell us their stories. It’s a beautiful thing.

ALESSANDRO: It’s a really powerful gift to give someone. Room to express.

LOPEZ: It’s hard for me to guess what that is because I watch it through a very different lens than everybody else. I think that one of the things the play is really about is finally letting go of stories that we’ve been holding onto for a really long time. We always tell the actors who have big, long speeches in the play that ‘you have to deliver this as if you’ve never done this before.’ It’s the first time that Walter has told his story in years. It’s the first time that Margaret told her story. It’s the first time that Toby or Adam have told their stories. And it’s something they’ve been holding onto for a really long time, and we catch them at the moment when they’re ready to tell their story. Every character goes through a kind of change as a result of having told their story. And for the audience, they can take encouragement from the characters.

ALESSANDRO: That’s great. I just interviewed Édouard Louis.

LOPEZ: Oh, he’s coming this weekend!

ALESSANDRO: Yes, and he spoke about his novels (The End of Eddy and History of Violence) being adapted into plays at St. Ann’s Warehouse and BAM, both opening this week.

LOPEZ: We all open on the same night!

ALESSANDRO: I know, it’s been an eventful week. He said it was very freeing for him to no longer be burdened by carrying his story, and now someone else—the actors, the director—can tell it.

LOPEZ: I feel the same way.

ALESSANDRO: He also spoke about how for a writer who’s a member of a marginalized group—whether gay or black or Jewish or a woman—there is a relief to finally be able to say the things that have been historically unsayable. How does that resonate with you?

LOPEZ: Well, for me, I don’t think I necessarily wrote them from a place of being a member of any particular group, though I am, of course, a member of a number of groups, but I wrote things that were unsayable for me, from my life. A lot of things from my past. I talk very openly about my alcoholism and addiction in the play. Places that it took me. I write very honestly about my damage, things that were done to me, things that I’ve done to others. I never enumerate them—I don’t go through an annotated script and say, ‘This is me, or this is made up.’

ALESSANDRO: Of course.

LOPEZ: And more than just events, but feelings. I think sharing how something feels. So many times, I’ve been asked by people who have seen the play, ‘How do you know what I was feeling?’ The play expresses a feeling that they’ve had that has never been reflected back to them before and a feeling that has made them feel very lonely in the world, which is exactly the same thing that I’ve held onto that has made me feel lonely in the world. I thought I was so unique, with my pain and my damage and my trauma and my guilt. And in writing the play and letting go of that and sharing it, I actually realized that I’m not unique at all, and these things that I felt were so important to me and loomed large in my life, they have been shared by a lot of other people, and in telling it I have learned that there’s a great solace in learning that you’re not special. And whether they’re enormous things, like addiction, or tiny things, like how you feel about “Yas, Queen!”

To say something out loud for the first time for yourself is very freeing and scary. And hearing the play for the first time in the Young Vic was a terrifying experience. You know, personally, my aunt [Priscilla Lopez] was in the original company of A Chorus Line and she sang the song “Nothing,” which is a story about a very bad experience in a high school for the performing arts, which really happened to her in real life. She told that story to the creators of A Chorus Line, and they turned it into the song. And then she started performing it every night downtown at the Public Theater, and the first number she did in front of the audience, they laughed! And it’s a funny song! But she was so offended, and then her husband, my uncle, explained that it’s supposed to be a funny song. And a funny story, when you think about it. And she thought about that and how it allowed the audience to laugh, and it freed her from the pain of that experience.

ALESSANDRO: That’s great.

LOPEZ: I have let go of a lot of things working on this play. Things that were bound up in this play.

ALESSANDRO: Being able to articulate that difficult, elliptical thing that so many people feel, does it give you a sense of responsibility? Does it feel weighty?

LOPEZ: Well, it did. It felt weighty in a personal way, but then when I saw how the play was being responded to as well as it was, then I just felt a responsibility to continue to explore the play as we were developing it from one production to the next. Once I realized that it was landing on receptive ears and being received warmly and with a reciprocal willingness to engage, I felt a responsibility that it was living up to the expectations of its author, its creator, and its audience, so I think it came later. David Lan [the assistant director at the Young Vic at the time] said to me after the play opened at the Young Vic, “Now you just have to protect the play and make sure that the audience always feels this way as you make it better.”

ALESSANDRO: Not to be too melodramatic, but what was the first indication that this was going to be something culturally seismic?

LOPEZ: [Laughs.] I try to keep a cautious distance from all that because I have this fear that if I look down, I’ll fall. My fear of heights will kick in and then I’ll feel self-conscious, and I never want the play to feel self-conscious. I never want to make decisions about the play based on anything other than what I learn about the reception in the theater every night. I wrote this play never imagining that it would ever get this far. I really did just think I was going to scratch an itch and have it done at Hartford Stage, where it was originally commissioned. Maybe over the course of the run, 7,000 people would see it if we were lucky and that would be that. And then the ambitions of it just kept growing as I worked on it.

ALESSANDRO: And you’re still tweaking?

LOPEZ: Still tweaking, yeah. Putting in a couple of changes tomorrow (three days shy of the official opening on November 17th). It slowly dawned on me that this was something that was resonating with audiences. The first performance at the Young Vic was so illuminating. I didn’t know how funny the play was until I saw it in front of an audience. I hoped it would be funny but I … [yawns] Sorry, this shot is, like, making me loopy.

ALESSANDRO: [Laughs.] The B-12 shot?

[Lopez had just received his first B-12 shot with the cast minutes before the interview.]

LOPEZ: Yes, the B-12 shot! Not a shot of whiskey! I’m not relapsing, Mom! I’m not relapsing! I am doing my best to not allow myself to read my own press, as it were. I just need to make sure I’m doing the best work possible. I try to stay in a little bit of an airtight bubble. I am not on Twitter. I’m not on Facebook. I am on Instagram, but I don’t go on when I’m in previews.

ALESSANDRO: Self-preserving? Play-preserving?

LOPEZ: Self-preserving, play-preserving. I don’t want to respond to the things I read. Before social media, you learned about your play every night in the audience and you weren’t privy to the conversations that audience members had over drinks later, you don’t follow the couple home and listen to their conversation on the subway. You can’t listen to 800 different voices.

ALESSANDRO: There’s something romantic about not being subjected to that.

LOPEZ: I can’t allow myself to do that. Jonathan Tolins [playwright of Buyer & Celler] said that individual audience members are often wrong, but an audience is never wrong. And that was something I really took to heart.

ALESSANDRO: Are British audiences different from American or New York audiences?

LOPEZ: American audiences have been more vociferous. They see themselves in the play. And I’m surprised by how much the London audiences saw themselves in the play. The New York audiences love all the New York references.

ALESSANDRO: Of course!

LOPEZ: Rent control gets a great response here. Never got a response in London. And of course, we’re in the middle of “Luger-gate,” as I call it. And the Peter Luger references have taken on a different meaning for NY audiences now, which has been fun to watch. It’s the hometown response.

But the London audiences have been very warm. And not to put too fine a point on it, it’s because of the London audience that we’re here today. They were vital to the success, but the NY audience is louder!

ALESSANDRO: The Inheritance is receiving inevitable comparisons to Angels in America.

LOPEZ: I’ve been told.

ALESSANDRO: [Laughs.] How do you feel about those comparisons? Are they fair?

LOPEZ: I don’t know if it is fair. I find them to be very superficial comparisons.

ALESSANDRO: Gay. Six-and-a-half hours.

LOPEZ: Gay. Six-and-a-half hours. You know, two parts. They’re very different plays and they have very different goals, written at very different times. What is true is that I’m a 42-year-old playwright who studied Angels in America in every class in college. There isn’t a part of my life that is untouched by that play. For my generation, and as a gay man in particular, that play is enormously important to me. It’s hard to convince people of this, but I was not swinging at those fences when I began to work on this play. I never sat down and said I am going to write Angels in America—my version of it. I didn’t even know I was writing a two-part play, at first. It just kept growing. It just kept telling me what it was. I never wrote a play that kept informing me what it wanted to be, which sounds a little silly or New Agey to say. But it’s true. Its dimensions revealed themselves.

ALESSANDRO: When did you start writing it?

LOPEZ: I started in the summer of 2008. I finally got the commission from Hartford Stage in the fall of 2012. And in January of 2013, I began keeping a notebook. And kept questioning myself, ‘can I do this,’ and began outlining. I started to write it in the winter of 2015. In the spring of 2016, I wrote part two.

ALESSANDRO: And then you started to pull in current events. Obviously, the election.

LOPEZ: We had already done a workshop in the city with Stephen [Daldry, the director]. And then that happened!

ALESSANDRO: You couldn’t ignore it.

LOPEZ: And then Stephen called me two nights after the election and he was like, “I hate to say this” and I was like, “I know exactly what you’re going to say, and I know you’re right.” So, then I went back and wrote the play again. I mean, I didn’t have to throw it all out. But that was when the timeline became codified into the play. That’s when the notions of the celebrations that we do in Part I, Eric’s birthday, become important. The first time we meet Eric is at his birthday party and then we have Walter’s birthday party. And then at the epilogue, it’s Eric’s 40th birthday, and that’s when I conceived of the play having a timeline. A clear and rigorous timeline. Because I knew where I wanted to put the election. And everything flowed from there.

ALESSANDRO: You never mention Trump by name in the play. What was the motivation there?

LOPEZ: I just didn’t want to hear his fucking name. It would ruin the magic.

ALESSANDRO: Coverage of him is already saturating the media. We don’t need to hear it in a theater.

LOPEZ: You’re casting a spell over the audience, and I can’t think of any worse way to break that spell, so we say, “that man.”

ALESSANDRO: I love that about the play. I thought it was wonderful.

LOPEZ: We’ll say Clinton’s name, we’ll say Obama’s name, and we used to say Mitt Romney’s name. I was fine with that, but it was cut in previews. But Trump is “that man.”

ALESSANDRO: Does Trump represent a new phenomenon, or is he the result of decades’ worth of sentiment and policy—an exaggerated, satiric version of previous politicians and leaders?

LOPEZ: Trump is the bottom feeder of the swamp that was started by Richard Nixon in his Southern Strategy. I think Trump is the apotheosis of all that Richard Nixon dreamed of. I suspect that Nixon would be horrified by Donald Trump, though.

ALESSANDRO: He’s just so artless.

LOPEZ: Nixon was, after all, a Quaker, and Nixon was a far better criminal than Trump.

ALESSANDRO: Somewhat slyer.

LOPEZ: To be generous to him, [Trump] is perhaps the most brilliant political mind since Lyndon Johnson.

ALESSANDRO: You can’t even satirize him. Armando Iannucci, the creator of Veep, was asked to create a satire about him, and he said he can’t because he’s already self-parodying.

LOPEZ: He’s brilliant in the most pernicious way. What’s so sad is that he has taken everything over the past forty years in American politics and woven it together into this tapestry of awfulness. He didn’t invent anything. He’s a greatest hits album.

ALESSANDRO: The most derivative leader.

LOEPZ: In that regard, he’s the world’s greatest DJ, and he’s put it all into this one mix to create something as dangerous as you could possibly imagine.

ALESSANDRO: You’ve spoken volubly about how EM Forester’s Howard’s End influenced you in your youth, and Maurice makes multiple appearances in The Inheritance. Who were some of your other influences while growing up?

LOPEZ: I was really under the spell, as a playwright, of both Eugene O’Neill and August Wilson. They were the two tentpoles of my formative years. As a novelist, I think the first quasi-contemporary of mine who really spoke to me, even though we’re from different cultures, is Zadie Smith. She’s so important to me. And she’s also done her Howard’s End.

ALESSANDRO: On Beauty, yeah.

LOPEZ: Zadie Smith has the ability to hold onto who she is while also still writing about the culture in which she lives. She can write universally and specifically, and she shows that the more specific you write, the more universal it becomes.

ALESSANDRO: She’s so generous. I interviewed her about a year-and-a-half ago.

LOPEZ: She’s so wonderful.

ALESSANDRO: Has she seen the play, yet? I know you mention her in Part I.

LOPEZ: Not to my knowledge. I tried to get her to come when we were in London. I ran into her at Housing Works on Crosby Street and I was waiting for the bathroom and then she came out and I was reading On Beauty, it was in my bag, and then I gasped, “I’m peeing after Zadie Smith.” [Laughs.] And I hunted her down in the store and had her sign my book. James Baldwin is also so important to me.

ALESSANDRO: Have you seen Slave Play yet?

LOPEZ: At New York Theatre Workshop and also on Broadway at the Golden Theatre. What he does in that play is so … what I said about Zadie Smith holds true for Jeremy (O. Harris). There’s so much Jeremy in that play, and yet it never eats the play. It never subsumes the play. The play is the play, but he is shot through in every character and every argument. And I find the play to be wildly intelligent. He’s a born showman.

ALESSANDRO: What was it like working with Stephen Daldry?

LOPEZ: He makes every room feel like a party, and he makes every person feel brave enough to throw their oar in the water. The actors are given so much encouragement to invent and have ownership over their performances. He comes from the school of ‘the actor directs the performance and the director directs the play.’ He has created some of the most honest acting I’ve ever seen on stage in a play with The Inheritance.

ALESSANDRO: Because he gives the actors the space to create?

LOPEZ: He gives them the space.

ALESSANDRO: It’s trust.

LOPEZ: It’s trust. And he knows it’s not the actor’s character, it’s the writer’s character. It is the actor’s role. And therefore, they have a lot of leeway and therefore a lot of responsibility to create as fully imagined a performance as possible and his job is to not hinder that. It’s the first play of mine that I did not know how to stage. Stephen came along, and from the very first workshop he had a basic idea. He formed a rectangle with a bunch of tables, and the actors were seated on the outside, and on the inside was the playing space. He’d say, ‘If you’re on the outside, stay on the outside and say your lines from your seat, but if you’re in the scene, go in the middle,’ and that’s what we do in the play. He has such a clear storytelling sense and he’s helped me. Part II was originally 326 pages long! The first time we read part II, it took over six hours to read. Part II alone! And now we have Part II shorter than Part I, because of Stephen. With all due respect to all of my past collaborators, it’s the most joyful and most respectful and the most wonderful collaboration I’ve ever had.

ALESSANDRO: Dare I ask, what is your next project?

LOPEZ: Ah! I have a workshop of Some Like It Hot in January. We’ve been working on it for two years now. We’re doing a musical of that. Marc Shaiman. Scott Wittman. Casey Nicholaw [Mean Girls and The Book of Mormon] will direct. We’re taking the movie and playing with it. We’re not doing a Xerox. We’re doing our own thing with it, which will probably appall the purists. But those who actually care about creating cool, dynamic, new musical theater will hopefully come along for the ride. I’m really excited about it. We don’t want to make it feel like a revival. We’ve updated the setting from the 1920s to the 1930s to incorporate the Depression. But we want to make it feel like it was written now. And I have a few film projects that I’m starting to work on.

ALESSANDRO: Screenwriting?

LOPEZ: Yes, in London, for me to direct. But in terms of plays, I have no idea what I’m going to do next.