BACKSTAGE

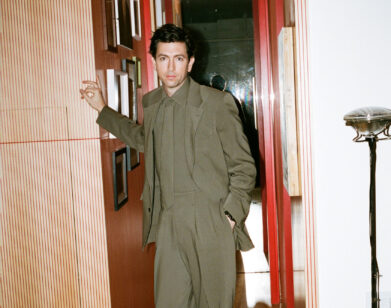

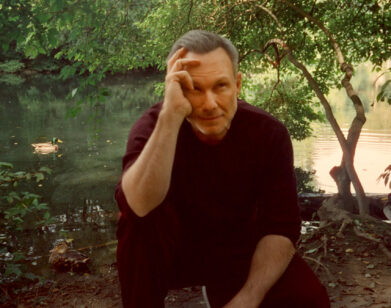

Kip Williams Tells Rose Byrne How He Pulled Off the Epic Technological Feats of Dorian Gray

In a crowded Broadway season, one particularly bravura performance has dominated headlines. In The Picture of Dorian Gray, an imaginative and sneakily prescient adaptation of the novel by Oscar Wilde, Sarah Snook of Succession plays 26 different parts, assuming different accents, costumes, and personas with a madcap energy befitting of the book’s greater meditations on youth, beauty, and vanity. The performance is as demanding as any you’ll see on stage, and it works in no small part because of Tony-nominated director Kip Williams, who called on every theatrical trick at his disposal to usher Dorian Gray into the 21st Century. As he told actor and fellow Australian Rose Byrne, “There’s over 300 marks on the stage, over 400 camera edits, Sarah does over 20 costume changes live, and there’s an onstage crew of about 25 people. So it’s like directing an ensemble piece of sorts.” And yet, for all of its technological innovations, the production also hearkens back to theater in its simplest form. “The fuselage of the whole thing,” says Byrne, “is this ancient idea of just telling the story.” Just after both Williams and Snook received Tony nominations for their work, Byrne got on Zoom from Sydney to ask the director about his earliest encounters with Oscar Wilde and the terrors of mass surveillance.

———

KIP WILLIAMS: Hey, Rose.

ROSE BYRNE: Hi, Kip.

WILLIAMS: How are you?

BYRNE: I’m great. Nice to see your face.

WILLIAMS: Nice to see you too. How’s things?

BYRNE: I’m good. Are you back in New York?

WILLIAMS: I get to New York Tuesday night, so I’m in Sydney right now.

BYRNE: What time is it in Sydney?

WILLIAMS: You know what? It’s light-ish, but we’ve had an election here.

BYRNE: I know, I know, I know, I know!

WILLIAMS: Amazing. A landslide.

BYRNE: Believe me, I’m on a family thread, as I’m sure you are, so that was what I woke up to.

WILLIAMS: It’s very exciting.

BYRNE: Well, first of all, bravo on the nominations.

WILLIAMS: Thank you. Thank you.

BYRNE: How did you feel?

WILLIAMS:Well, I’m a particularly proud director that the entire team was recognized.

BYRNE: When I saw Nick [Schlieper’s] name, I was like, “Oh my god.”

WILLIAMS: Schlieper is a Tony nominee. And my sister is the sound designer on the show as well.

BYRNE: Oh, I didn’t know.

WILLIAMS: She’s done such incredible work and she’s now a Tony nominee, too.

BYRNE: Well, that’s extraordinary. I wanted to ask you, what was your relationship with the novel before you adapted it?

WILLIAMS: Well, I had acted in a high school version of The Importance of Being Earnest when I was about 14 at an all-boys school, and I played Cecily Cardew. I played her for full psychological truth, and as a little queer theater kid in Sydney, it inspired within me this love of Oscar Wilde and his awareness of the way in which life is like a grand act of theater and we’re always performing our identity. Then I just read everything that he had ever written and cracked upon Dorian, which is his only novel. I was just utterly obsessed with it and, at that age and stage of my life, it was this sort of awakening. Never thought that I would turn it into a play at that point in time. It’s a challenging piece to make work as a work of theater, but it’s an astonishing piece of writing. So I just kept coming back to it over the years. And then I read a whole host of Victorian Gothic literature about seven years ago, thinking about how that was a sort of genesis period for a lot of the social questions that have been asked over the last century about individualism and public and private life. Oscar Wilde’s novel really struck me because it had this prophetic quality in that it envisaged a world that would become obsessed with youth and with beauty and obsessed with the individual—and that’s the world we’re living in now.

BYRNE: It’s extraordinary, isn’t it? I was also intrigued to read that you did a [Samuel] Beckett monologue at NIDA and you assigned it for 20 different performers. Is that right?

WILLIAMS: I did, yes.

BYRNE: So, what is this, this sort of theme you have? Because there’s a kernel of something in there that you’re doing.

WILLIAMS: You’ve hit the nail on the head. I think I’m very interested in the idea of a human containing multitudes, and this notion that we are actually quite contradictory and paradoxical creatures, that we’re shape-shifters. And depending on the context in which we’re in, we adopt a different mode of our identity. And in the case of Beckett’s “Not I,” it’s a single-sentence monologue about a character who is talking about themselves, but she’s in complete denial that she’s talking about herself. Hence the title, “Not I”.

BYRNE: That’s amazing.

WILLIAMS: When I read it, it read to me as a conversation in someone’s mind about themselves, so I adapted it for 19 speaking actors and one silent actor.

BYRNE: Wow.

WILLIAMS: And I guess Dorian is a kind of inverse of that notion in that the form that I conceived of for this play was one actor playing all of the roles. And that theatrical form would express what Wilde expresses in the novel, which is that a human is a being with myriad lives and myriad sensations, “a complex multiform creature,” to quote Wilde. I actually finished the first draft of the play and pitched the directorial vision without knowing this, but a friend gave me a letter of Wilde’s where he writes about the three central characters being expressions of three different facets of his identity. When I read that I went, “Okay, my concept for this piece is…”

BYRNE: It’s like the ultimate code-switch.

WILLIAMS: Yes, exactly.

BYRNE: I’m intrigued by so many things about this production, but bringing it all the way from Australia to Broadway, what was that like?

WILLIAMS: I mean, there’s the feeling of elation and nerves and excitement that you’re bringing a work of art to one of the great theater cities of the world.

BYRNE: The great one.

WILLIAMS: Yeah, it’s kind of amazing in that sense. But I was also aware that there’s this special relationship that New York has with Oscar Wilde. He’d had these series of failures in the UK and in London in the early stages of his career. No one was really taking him seriously. And then he came to New York and began a speaking tour that was this humongous success. I think Americans got him, but it took a while for London to really hear the sort of subversive critique of the class and social power structures that’s so at the core of everything he writes. He’s such an iconic queer thinker, an outsider, and he was able to critique his own environment because of that. But it took him going to a city like New York that’s full of outsiders to really be discovered and understood and celebrated, so I was acutely aware of that. And that’s really rung true in how audiences have responded to it. There’s an embrace and a resonance in New York that is unlike any of the cities that this show has played in before.

BYRNE: When it was on the West End, did you feel more—

WILLIAMS: Terror?

BYRNE: Well, I get it. They’re the toughest.

WILLIAMS: That was nerve-wracking because it was bringing a story set in London back to London in a theater that was Oscar Wilde’s favorite theater on the West End that had a room in the theater called The Oscar Wilde Room.

BYRNE: And by an Australian, the ultimate underdog.

WILLIAMS: Oh, yeah. But I do think the perspective that’s been brought to this story is very in keeping with Wilde and his playfulness, his subversion, his risk-taking. And I do think for myself, being kind of an outsider to the British culture allowed me to have freedom with it and to dream in a very big and bold way.

BYRNE: And if I may, how many days is the tech? But maybe we should explain what tech is…

WILLIAMS: I love tech because you’re in the theater for the first time and you’re actually seeing all of the parts come together. Up until that point, the team and I are working a lot in hypotheticals because of the screens and how they operate within this piece. They dance and they move, they’re very kinetic, and you don’t get all of those elements until the theater magic happens in tech. It’s a show where there’s over 300 marks on the stage, over 400 camera edits, Sarah does over 20 costume changes live, and there’s an onstage crew of about 25 people. So it’s like directing an ensemble piece of sorts. And this is also where Sarah and I connect so very deeply—we like to keep working.

BYRNE: And if I may, this is really a question for Sarah, but I’m going to be sneaky and ask you. What are the challenges in doing this incredible piece with the technology? I’ve never done anything like it.

WILLIAMS: Well, they’re massive. I mean, it’s like a marathon. It’s so physically demanding on her body, on her voice, and on her brain, the sheer task of remembering thousands of words and hitting those cues with micro-precision. But probably the biggest challenge is that it’s all live. Everything she does is live.

BYRNE: It’s so purely theatrical, isn’t it? Anything could go wrong. And you truly appreciate that as an audience member; you really do see the detail. There’s nothing unthought out, yet it feels very spontaneous, which is hard to pull off.

WILLIAMS: Well, the number one thing I knew when I conceived of the piece was that I was going to use a lot of technology in it. I had some very clear ideas for how the cameras were going to work, how the screens were going to work. But I knew that, for all its contemporary technology, it was going to be a very ancient form of theater-making, which is an actor coming to an audience to tell you a story. The number one rule of the piece was that Sarah would be live the entire night and that she would be the motor of this incredible theater machine, and I think that’s why it works. Audiences come away very acutely aware of how the technology has operated within the piece and how contemporary that feels, but they’ve been held within that story and theater form by that ancient idea of an actor talking to you and activating your imagination.

BYRNE: I feel like it’s so important to acknowledge that, you know what I mean? Holding that centrifugal thing, the fuselage of the whole thing, is this ancient idea of just telling the story. But the other thing I took away was the idea of surveillance, the idea that we’ve just leaned more and more into this obsession with our own narrative, our own story, our own presentation to the world through social media. And that, to me, was a delightful and horrible kind of reckoning. This book was written, how many—?

WILLIAMS: 135 years ago.

BYRNE: Fucking extraordinary, extraordinary how uncomfortable the resonance of it felt.

WILLIAMS: Yes. And obviously, Wilde could never know that the mobile phone was coming.

BYRNE: I know.

WILLIAMS: There’s lots of amazing things that come from it, and there’s lots of challenging things that come from it, but it ultimately will be a mirror to human behavior. It doesn’t create new human behavior, it will exacerbate it. So the sort of performance that we do online, that’s not a new human phenomenon. It’s part of the human experience to perform ideas of who you are. It’s just that social media and the mobile phone have turned the volume up.

BYRNE: It’s like we’re drowning in it.

WILLIAMS: We’re not meant to be doing it every 30 seconds.

BYRNE: We can’t have that much stimulation. I read that you would love to do the opening ceremony of the Olympics. I just thought that was brilliant, in that it’s one of the ultimate expressions of grand theatrics in our culture. I hope you get to do it one day.

WILLIAMS: If I do that, you have to come and perform in it. I’ve always obsessively watched the Opening Ceremony on YouTube.

BYRNE: Have you?

WILLIAMS: Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah. I think what’s beautiful about them is that they are grand acts of storytelling, visual acts of storytelling, often without words. And because you’re communicating to cultures all over the world who speak hundreds of different languages, the visual storytelling in them is profound.

BYRNE: What about the Super Bowl halftime? That’s a pretty fun show.

WILLIAMS: That would be amazing. I loved the Beyonce Bowl with Cowboy Carter.

ROSE BYRNE: She’s making history live. You know what I mean? You’re watching it unfold and you see it.

WILLIAMS: She is a genius theater maker. She knows how to tell a story visually.

BYRNE: Well, it’s been so lovely to see your face.

WILLIAMS: Likewise.

BYRNE: And bravo, bravo, bravo, bravo.

WILLIAMS: Thank you, Rose. I’d love to see you and Bobby [Cannavale] soon.

BYRNE: Oh, yeah. We’ll see you soon.