Hilton Als Wants to Save James Baldwin From Us All

Sitting in the dining room of the Metrograph theater one recent evening, Hilton Als, the New Yorker critic and calm purveyor of aesthetic values, ordered two Diet Cokes. One for himself and the other, despite saying nothing of a drink at all, for me. Als returned to the question of a New York Times review about his latest curatorial effort, a group exhibition of works visualizing the life of James Baldwin. Tucking a napkin into the collar of his sweater, he said, “It made me sad in a way. It’s about a moment in history, right, but it’s also about his life as a gay person. I wanted to say it’s about cruising, too! How could you not see that?”

We raised our non-alcoholic drinks, fizzing inaudibly under the buzz of a Friday night dining crowd. His order of pâté, Caesar salad, and cauliflower cake arrived at the table. “I don’t know if this is real or not, but it seems that people are afraid of Baldwin’s sexuality. Why is that?” he asked. Als smeared pâté onto a corner of white toast. He laughed airily, amused at the obviousness of the question. “You’re a young person. You tell me.”

Als was at the theater that night to introduce the first of several films featuring Baldwin for two nights of programming he’d curated as a kind of conceptual twin to the group show, which is on display until mid-February at the David Zwirner Gallery. That show, God Made My Face: A Collective Portrait of James Baldwin, works like a tonal arrangement of perspectives on Baldwin, and of Baldwin — his emotions, his fantasies, his desires, the collected essences of a man who once walked the streets of New York City and Paris. An artist who was so successful in his time as an intellectual voice and authority on civil rights, that the other humanizing details of his life — his queerness, his exile from home, his vulnerabilities as an artist — have been lost in the mythologizing. Something more real, and possibly more political, could emerge if we looked at Baldwin in full, Als suggested. As he said in a recent interview, “We need to give him back to himself.”

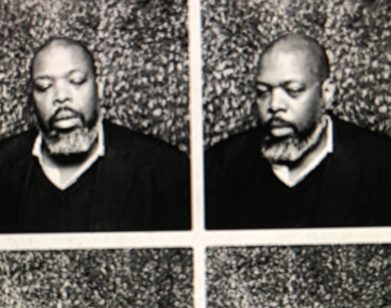

Collected in the Zwirner show are periods stretching from a speculative contemporary moment with works by Kara Walker and Marlene Dumas, back to a nostalgic mid-way with Richard Avedon’s famous portrait of Baldwin and photos by Alvin Baltrop, working all the way back to the turn of the century with Eugène Atget’s snapshots of Parisian streets. The show works, in a way, to answer Als’s first question by visualizing the space inhabited by Baldwin. “That was a stated rule of the show for me: how do you make consciousness real to other people? I’m trying to make a person alive.”

One analogy to explain the task at hand is translation, Als pointed out while cutting into a loaf of cauliflower cake. (“Don’t worry, I can talk and eat,” he said.) The act of translation, he continued, is a familiar labor to any black writer, Baldwin being one of the most visible examples in the last 50 years. He was, perhaps unfairly, tasked with relaying one group’s experiences to another vastly disparate group, marked by differences in race, sexuality, nationality, and age. Our drinks were watery by now. It was time for Als to translate another unseen chapter of Baldwin’s legacy for an audience downstairs. “I don’t really mind it. It’s like writing sonnets in a way. There are certain rules you have to follow,” he said. “But there’s always the rule of lyricism.”