David Hockney

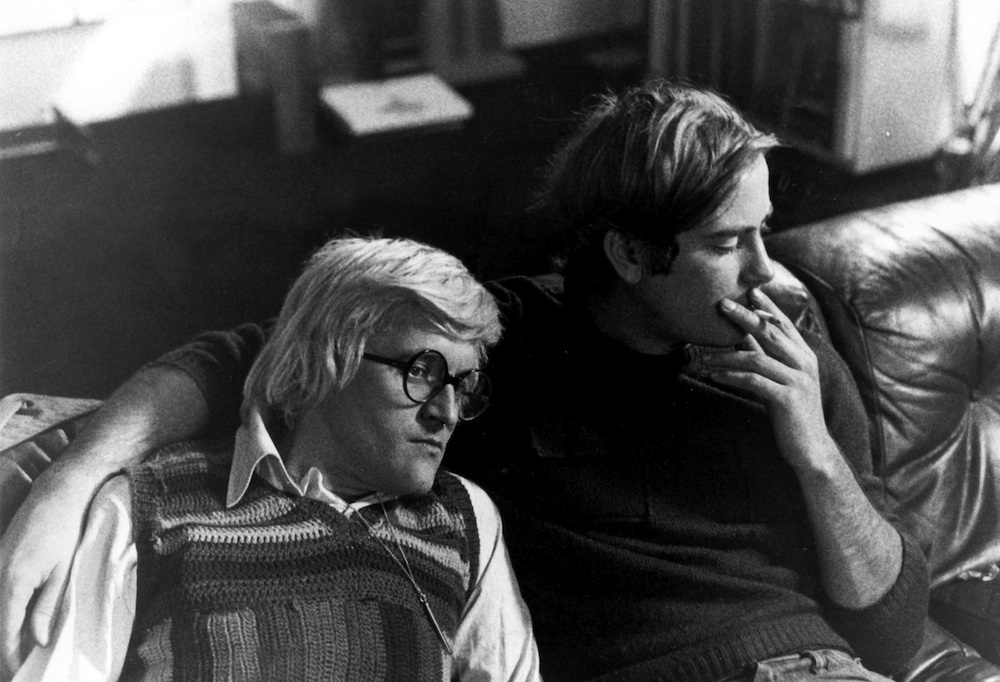

ABOVE: HOCKNEY AND PETER SCHLESINGER IN A BIGGER SPLASH (1974). PHOTO: REX USA/MOVIESTORE COLLECTION/REX.

I’m really only interested in technology that is about pictures. I’m interested in anything that makes a picture dAVID HOCKNEY

Known for his paintings of the Yorkshire countryside and the swimming pools of Los Angeles, for his many striking portraits, as well as his still-life compositions—which these days, might very well be drawn on an iPad—76-year-old David Hockney has pursued traditional subjects by often untraditional means for more than 50 years. Hockney set the standard for pop art in postwar U.K. and came to define the social whirl of ’60s London. He has never been afraid to experiment or ruffle the feathers of art historians—specifically with his conjectures about the prevalent use of the camera in painting centuries before commonly thought.

A painter first and foremost, the Bradford-born Hockney has always embraced picture-making technologies, from the fax machine to the digital video camera. Especially admired are his Cubist-like collages comprised of Polaroid instant snapshots from the early ’80s. His iPad drawings were featured in his 2012 exhibition at the Royal Academy in London, and his upcoming exhibition at the San Francisco’s de Young Museum will include recent large filmic works made with an array of inexpensive digital video cameras. The Los Angeles County Museum of Art is exhibiting one of these new filmic works this month, honoring Hockney along with Martin Scorsese at its Art+Film Gala.

While he keeps one foot in his native U.K., with a studio and house in Northern England, Hockney has lived on and off in L.A. for roughly 30 years. Some of his most admired works were created there. LACMA, too, has had a long history with the artist—from his first defining retrospective in 1988, curated by Stephanie Barron and Maurice Tuchman, to his more recent exhibition of portraits coordinated by Barron. His 20-foot-long Mulholland Drive: The Road to the Studio, from 1980, is among the museum’s most beloved masterworks.

Earlier this year, Hockney worked on a large series of landscape drawings of the Yorkshire countryside in simple black and white, made in five locations over the course of winter and spring. Enlarged digitally and printed at four times their actual size and displayed as a large grid, they will be first seen by the public in his San Francisco exhibition. I was able to see them in his Hollywood Hills studio and speak with him about painting and drawing, technology and movies.

MICHAEL GOVAN: Here in your L.A. studio I’m looking at a huge grid of black-and-white landscape drawings on two walls.

DAVID HOCKNEY: They’re actually printed enlargements of my drawings. They’re enlarged to four times the size of the original drawings

GOVAN: How do you make landscapes and portraits in the 21st century?

HOCKNEY: The art world thinks you can’t do them.

GOVAN: Well, you can make them.

HOCKNEY: I can do them.

GOVAN: As I’m looking at these landscapes, I’m reminded of what you’ve said before, and it’s worth saying again: “Everything comes from nature.”

HOCKNEY: Everything does come from nature. That’s where you get new ideas. Just draw the landscape. I felt doing it with a bit of burnt wood was also good because I was drawing burnt wood with a piece of wood. I wanted to do black and white. After using color, I thought black and white would be good. You can have color in black and white. There is color in them, actually.

GOVAN: Hung in this large grid, they remind me of the fractured video grids that you’ve been doing, such as the series of videos you made while driving around in your car from 2010 to 2012, displayed on nine or 18 screens at once. It seems to me there’s a relationship between these drawings and your video works. Is that accidental?

HOCKNEY: No, it’s not accidental. That’s how I had arranged the drawings in my little bedroom in Bridlington. I wanted five pieces with five across and five down. But I nearly gave up actually. Even in the last two days, I nearly gave up. I did two of them in one day. And I did another the day after because it was going to be a sunny morning so I was going to get shadows and things like that. The sun would be different from the previous ones. It was a lovely thing to do.

GOVAN: It’s interesting that we’re talking about nature and landscape, but you yourself have never been afraid of technology. You’ve been the first to embrace machines, from your Polaroid collages in the 1980s to your iPhone drawings in 2008. And now you’re working with digital video and printing. I was taken aback by seeing your works made from multiple video images because I’d never seen anything like it anywhere—in any medium. It did what drawing couldn’t quite do, it did what film couldn’t do. You embrace new technology.

HOCKNEY: I’m really only interested in technology that is about pictures. I’m interested in anything that makes a picture. I was always interested in photography because it makes a picture. And even fax machines, when I found out you could make a picture if you did them right. There’s no such thing as a bad printing machine. So long as it prints, it’s doing something. If you feed the right things into it, the right things will come out of it. I’ve always gone into anything technological. I’m convinced that technology and art go together—and always have, for centuries. I pointed that out in Secret Knowledge [Hockney’s 2001 book positing that artists like Caravaggio and Da Vinci used lenses and optics to create their paintings]. I think it began in about 1420. What the art historians had forgotten is that in Chinese, Japanese, Persian, and Indian art, they never painted shadows. Why did they paint shadows in European art? Shadows are because of optics. Optics need shadows and strong light. Strong light makes the deepest shadows. It took me a few years to realize fully that the art historians didn’t grasp that. There are a lot of interesting new things, ideas, pictures.

GOVAN: You once said that one of the reasons you were interested in moving to Southern California was for the strong light.

HOCKNEY: That is one reason, yes. Hollywood is here because of the strong light. I noticed that in early Laurel and Hardy movies—especially the one where they’re selling Christmas trees and they’ve got overcoats on—they had very, very strong shadows on the pavement. I knew even when I saw this when I was 8 years old, that you don’t get that in Bradford. You don’t get much sun in Bradford. I knew California was a sunny place with good light. And it is. It’s ten times brighter here than in England.

I feel 30. Picasso said healways felt 30. Well, I do. DAvid hockney

GOVAN: You feel it. So, the motion picture—you’ve always been involved in motion in some way. Is there something fundamental about the moving picture? I know how it tells a story, but what about seeing? That seems to be what you’re playing with in your new video works.

HOCKNEY: For instance, in the new works, in The Jugglers [a 2012 video work of a group of jugglers displayed on a grid of 18 screens], when you’re watching it, you can only see certain bits. You can’t see the whole thing. You can only watch two or three jugglers at a time. They move around and yet the background is static. Absolutely static. Well, to do that with one camera, you’d be too far back. You can’t do it with one camera. I’m pretty certain that that’s the way forward, actually—using multiple cameras. 3-D isn’t the way forward at all. 3-D is nothing. It’s just a novelty. If it’s in real 3-D, you could look around—but no director is going to let you do that.

GOVAN: It’s a Renaissance-style “window” at best.

HOCKNEY: The editing of moving pictures is geared toward the single image. You’d have to edit things in new ways. [Director] Peter Greenaway said that film was just beginning. I can see that. But I can see that cinema seems to be finished. Everybody has a bigger screen at home. I’m assuming eventually you won’t need a screen at all—these iPhones will just project. Now you can see things rather well at home. It’s a pretty clear, high-definition picture. But the high-definition picture is still a perspective picture. That’s the real problem, the perspective picture.

GOVAN: Which you address in The Jugglers by using the painter’s tricks, the way you flattened foreground and background by painting the columns in the room to match the colors of the floor and wall, which tied everything together into an ambiguous, flat space.

HOCKNEY: It’s why I’d like to show that work in China. The Chinese would see it straightaway—they’d see it’s like a scroll. Our cameras were slightly looking down because we didn’t want the juggler in the back to be at the back. So we had to build a stand. Just letting people have these ideas will stimulate ideas. It’s cheap now, putting cameras together. The little camera we used for the car—a little $200 one—we put three or four on the car and did the drive on it. The cameras are getting smaller, they’re getting more versatile, and eventually, I’m sure you’ll have a camera with lots and lots of things on it so you can alter the picture. You could alter perspective. I think we’re in a very exciting time—visually, I think we are. I’ve not got a crystal ball. I’m not saying I know what the future is at all. In some ways I’m getting quite pessimistic about the future, but in other ways I think it might get better. We are moving into very big changes.

GOVAN: When I saw The Jugglers, I was thinking about something you said: The cinema comes inside a room, but it’s a moving painting. It has so many qualities of painting as you flatten foreground and background. You created ambiguity, not perspectival space. You also introduced chance. I noticed you didn’t use super-professional jugglers—they were amateurs, so things would drop, which seemed also to do with breaking vision a little bit. It wasn’t a seamless whole. It had that quality of painting where a brush mark or disjunction creates a different kind of unity that is not one of a perspectival or one-to-one analog match. I thought of it as a “motion painting,” if you will. Whereas “Drive” has a different kind of narrative. It is a motion painting in a landscape but is a little different, because the background is less static.

HOCKNEY: The interesting thing is I was never that interested in movies. I was interested in them as a thing, but I didn’t want to make movies. I always wanted to draw and paint. What’s the point? [The late director] John Schlesinger told me this story of a secretary who used to work at the Chicago Art Institute. After that, the secretary worked for this Hollywood director, and he said to her, “You don’t stop going to the museum because those pictures don’t talk and they don’t move and they last longer.” I thought, Oh, that’s very good. Yes, they do last longer. It was interesting. When they did an exhibition at the Getty of the portraits of Sarah Siddons who was an actress in the 18th century, the only reason she’s known today is because she was painted by Reynolds, Thomas Lawrence, and Gainsborough. Hollywood might be the same. Movie actors disappear—any young person wouldn’t know Cary Grant. They’re going to disappear. Fifty years ago, you thought film was here to stay. But nothing is here to stay, actually—except perhaps paintings and drawings.

GOVAN: Portraits and landscapes.

HOCKNEY: Painting and drawing has been here for 35,000 years.

GOVAN: It’s got a good track record.

HOCKNEY: Why would you give it up today just because a photograph has come along? It’s madness. It’s just temporary.

GOVAN: When you talk about the lasting quality, is it the stillness that holds it and makes it timeless? Or is it the hand-made quality? Is that its energy?

HOCKNEY: I think it is the stillness. I think we seem to remember things in still pictures. I never gave up on painting. When they said painting was dead, I just thought, Well, that’s all about photography, and photography’s not that interesting, and it’s changing anyway.

GOVAN: Photography is becoming closer to painting now.

HOCKNEY: Yes, it is, because of Photoshop. It came out of painting, and now it’s going back to painting.

GOVAN: Early photographs were printed on canvas-like paper to make them “paintings” in the 19th century. Now there’s a merger again because people are painting on photographs.

HOCKNEY: By 1860 there were photographs being made that were collages, really, meaning that they were a few negatives put together. There would be interiors, and outside the window would be very clear. You couldn’t photograph an interior with the outside clear, otherwise the interior would be too dark. They were doing what painters did. These photographs have always been dismissed a bit by the purists—this wasn’t “pure photography.” But it’s always coming back now. This is what Jeff Wall is doing, isn’t it? It’s Photoshop—that’s what’s doing it. You can’t believe any picture nowadays, if it’s digital. You can’t really believe. If you see me shaking hands with Mr. Obama, it doesn’t mean I ever met him, does it?

GOVAN: So what is it that we look for? It’s not a verisimilitude or a document; it’s another kind of belief that we invest in a picture, a painting, something we see and love. It’s something else.

HOCKNEY: Paintings are different from photographs. Paintings are handmade, for a start, and therefore have some time in them. In The Jugglers you have 18 separate times. In an ordinary photograph, it’s the same time in the left-hand corner of a picture as in the right-hand corner of the picture. In reality, it’s different times—you take time to see it, you take time to move in it. Time is the great mystery anyway, isn’t it? And it’s still the great mystery in the moving picture as well.

GOVAN: At LACMA, we did an exhibition not long ago about Salvador Dalí and film. What was clear to me was that sometimes you think of film coming out of painting, but if you look at Dalí’s surrealist painting, it was actually Buñuel’s ability in film to displace time that inspires the painter to struggle for a way to reconsider time in painting, which exists. In that case, it was clear that the film was generative; it was easier to displace time in film, but then the painter found a way to displace time because painting engages time in its experience and what it conveys.

HOCKNEY: It’s interesting. In the movie Metropolis [1927], there are no images in its idea of the future.

GOVAN: There are no paintings, no photographs?

Drawing takes time. A line has time in it. David Hockney

HOCKNEY: It took me a while to see that. The third time I saw it, I thought, It’s very odd that they are making a film that was seen by everybody at the time—a million-dollar movie—and the future contains no images.

GOVAN: I never thought of that.

HOCKNEY: Even the posters were just words. There were no images. Also that scene right at the beginning of the film, where there are all these shots of workers coming out of work, was done with one camera. It makes everybody look the same, whereas if you’d used 18 cameras, you’d look at it differently. You’d look at the people differently. Well, this film was seen by Hitler and Goebbels—they must have seen it. Their attitude to the masses was terrible.

GOVAN: Single point of view.

HOCKNEY: And then you think, Well, not long after that film came out, was when they starved all the peasants in the Ukraine. Even today not many people know about that—three or four million it was. Did this picture of the masses make them feel, Well, they’re all nobody? Whereas with 18 cameras, they all would have been somebody.

GOVAN: It’s something very powerful, what you’re saying. It’s the same thing about point of view and perspective. Everyone was talking about your Polaroid works in terms of Cubism or multiple perspectives. There are many ways to express that, and I’ve noticed that you have explored multiple perspectives all the time. This huge series of drawings is about multiple perspectives, and the films, 18 cameras, the Polaroids. You even do double portraits frequently, which is one of your signatures. It seems to be that you are often trying to break the singular viewpoint.

HOCKNEY: It’s hard. I think photography has made us see the landscape in a very dull way—that’s one of its effects. It’s not spatial. A landscape is a spatial thrill to me. Photography sees surfaces, it doesn’t see space. We see space but the camera doesn’t.

GOVAN: When I think about it, even when I look at a painting that I see every day—your huge Mulholland Drive: The Road to the Studio at LACMA—I see how each part of that painting expresses space. In it, there is motion, there is a narrative, there are multiple points of view, and it has a spatial complexity.

HOCKNEY: I’ve always been interested in space in pictures. I think my going deaf increased my spatial sense, because I can’t get the direction of sound. I feel that I see space very clearly, and that’s because I can’t hear it. So it’s a compensatory thing. We don’t all see the same way at all. Even if I’m sitting looking at you, there is always the memory of you as well. And a memory is now. So someone who’s never met you before is seeing a different person. That’s bound to be the case. We all see something different. I assume most people don’t look very hard at anything. They scan the ground to make sure they don’t bump into things. But they don’t look very hard. I’ve always been a looker. Loads of people say, “I never saw that”—but that’s what artists do. The other thing, again, about shadows: do we see shadows? Loads of people don’t. A camera will notice a shadow, but how many people have got a shadow in front of them when they take a picture and don’t notice it, and then they see it in the photograph because the photograph will catch the shadow.

GOVAN: Isn’t that what the drawings are about?

HOCKNEY: In my film A Day on the Grand Canal With the Emperor of China [1988, made with director Philip Haas], one of the Jesuits who went to China in the 17th century learned Chinese very quickly, and he painted a portrait of the empress. And her comment on it was, “I can assure you that the right side of my face is the same color as the left side of my face.” It’s terrific, that comment on shadow, isn’t it? The Chinese ignored it, everybody did. Only the Europeans didn’t. And that’s why I’m sure that the camera is part of European art. I’m positive it is, because otherwise how do you explain it?

GOVAN: Wouldn’t you say that technological devices—especially the photograph—change how you see? I personally believe that movies changed the way we see also, even dream. We see in movie sequences. That’s the thing: a way of seeing can be forever embedded in looking at the world or making new pictures. I feel like I dream in movies, and I’m not sure people always dreamed in movies.

HOCKNEY: You haven’t seen the movie Tim’s Vermeer yet, have you? I’m sure it’s how Vermeer did his paintings, which changes the history of photography. The history of photography needs clearing out. It needs something else now. Because photography always acknowledged there were cameras before photography. Of course there were—how do you get the photograph? It’s the invention of chemicals, not the invention of the camera. It has made us see a certain way. In my film on the Chinese scrolls, I pointed out they didn’t have shadows, and you could do all kinds of things in that scroll, you went through a whole city. In a way, it was more like a film. All painters know there’s something wrong with perspective. Trees don’t obey the laws of perspective.

GOVAN: I always think you’re obsessed with trees, especially most recently, in part because they don’t obey perspective. They’re like big networks of lines you draw, like the big paintings you showed in L.A. not long ago and as I see now in these drawings. It seems like you use them to destroy that singular point of view. These huge series of printed drawings are really fantastic. One can look at these forever.

HOCKNEY: Yes, I think it’s one of my great works, actually.

GOVAN: I think the ambiguity of similarity and difference is very powerful. It’s the same scene in different times of year read across the grid, and, of course, different locations reading vertically. But you can get confused and lost in the series. You force the mind, which is always comparing and contrasting, to stumble … That ambiguity is very powerful. One is getting lost and refinding oneself.

HOCKNEY: I don’t suppose I’ll do it again. It took five months.

GOVAN: You’re going to show these prints with the original drawings they’re made from?

HOCKNEY: I’m going to show these in one room and the original drawings in another room. The drawings can be seen one person at a time. Here, you can take them all in. Done this scale, they have space; you can see the marks. I think it’s terrific. We couldn’t have printed anything like this eight years ago.

Fifty years ago, you thought film was here to stay. but Nothing is here to stay, actually—except perhaps paintings and drawings. David Hockney

GOVAN: If I were to compare it to any film, it would be certain aspects of Kurosawa’s films when you get that foliage and the lights and darks that have such energy. But better for your eye to move than the film to move. This really lets your eye move. There’s something analogous about these to the problem of the difference of seeing landscape versus making a picture of landscape. It’s hard to photograph a landscape because the experience of landscape is seeing everything in every direction and with your eyes across a vast, infinite field of vision. It’s spatial. What you’ve done here, which is so great, is that you’ve made a landscape of landscapes. It’s as if I could put my head inside the 3-D film. I have a much more emotional connection to landscape looking at these than one picture of a landscape. The volume, the intensity, the experience—because I’m looking a little bit the way I look at a real landscape. If I were inside that scene, I think I’d be doing the same thing. I’d be seeing similarity and difference as I distinguish one tree from another.

HOCKNEY: One person, when I was making the drawings, said, “What are you drawing?” “Just the trees.”

GOVAN: They’re very meditative.

HOCKNEY: All these were done after I had a mini-stroke. On the 31st of October last year, I had a mini-stroke. I couldn’t finish my sentences. So I went to the doctor. It was a tiny one. The speech came back in a month or so. I did notice I could draw even better, I felt. I was concentrating more. And I wasn’t talking much, but I was drawing. I said, “Well, I don’t have to talk much.”

GOVAN: Not to take the theme too far, but your comment about so many different kinds of mark-making, which again distinguishes a painting from a photograph—if indeed the marks are distinguished as they are in these drawings—is another way of breaking that singular, planar, perspective; a singular, monocular perspective. As you look at different kinds of renderings, you’ve fractured time again, on a single surface.

HOCKNEY: Drawing takes time. A line has time in it.

GOVAN: It’s very deliberate. You’ve chosen a way to represent a certain circumstance of light.

HOCKNEY: [points to a drawing of a fallen tree from his Vandalized Totem series] I was so shocked when it was chopped down, deliberately chopped down!

GOVAN: These have a memorial quality.

HOCKNEY: That’s England.

GOVAN: So you’re back in California. You like it here.

HOCKNEY: I do.

GOVAN: Except they don’t let you smoke here.

HOCKNEY: Well, I don’t go out much. I’m working here.

GOVAN: By the way, what should I call your new video pieces? Video, film, picture? We might have to invent a name for them.

HOCKNEY: I did try something similar in a television program in England 25 years ago or so. It was me and Melvyn Bragg, and they included a thing on my photography. For a segment of the show, I said, “Just get somebody to walk down these stairs, come forward, and sit in this chair. We’ll do it nine times, with nine separate pictures, but we only have one camera.” So we did it, and it worked. Parts of him sat down before other parts. When I saw it, I said, “Oh, this is fantastic. Let’s do it again.” He said, “Well, we can’t do it again, this just cost £25,000 to arrange!” Now it costs nothing. Melvyn told me the day after the broadcast, he was rung up by Peter Greenaway to ask how it was done. And then for 25 years I forgot about it, but remembered it when the cameras got smaller. Once the cameras had gotten to 35mm, I thought, We can put them together now, and we did. You saw the London Royal Academy exhibition film [Hockney filmed his “A Bigger Picture” exhibition, although it has not been publicly shown] that was using just three cameras. I thought using three cameras was a lot better than one, because you could see where you were going, where you’d been, and all kinds of things—more like life. I think photography has colored our vision. We’re now in an area where it might break something. I think this is a time. I feel it. I don’t know whether I’ll be here long enough to experience it. I’ve no plans to leave yet.

GOVAN: We have a young artist on our hands here.

HOCKNEY: I feel 30. Picasso said he always felt 30. Well, I do.

GOVAN: I don’t think a 30-year-old could actually make these drawings. There’s a lot of time spent thinking, there’s a lot of seeing.

HOCKNEY: I couldn’t have made this 10 years ago, because I couldn’t see it. It is a marvelous little road that I would point out. Every time I go on it, it looks different, which isn’t the case in California.

GOVAN: The differences are much more subtle in California. You learn to see differently here, that’s what I notice about California’s seasons—the shadows. The compensation for the lack of immediate cues of seasonal change in California is how you see the radical differences of shadows. It was being here, where the colors weren’t changing much, like a black-and-white picture, if you will, because you were habituated to it, that you notice the lines of shadows—”What’s wrong with this scene?” I would realize it was the darkness of the shadows are filling it. And when I was walking the same path, it was never in the same way. Here in these drawings you have so much subtly going on and changing. Congratulations. It’s an epic work.

HOCKNEY: I think it is. I think it is an epic. I’m very proud of it.