REUNION

Rhea Seehorn Walks Bob Odenkirk Through the Apocalypse

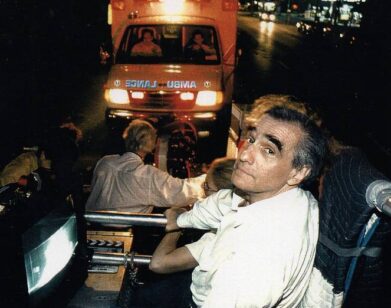

Rhea Seehorn, photographed by Matt Weinberger.

Rhea Seehorn spent six seasons as Vince Gilligan’s secret weapon on Better Call Saul, disappearing into her character Kim Wexler with such restraint that she became one of TV’s most riveting presences. Now, Gilligan—the man who helped redefine prestige TV with Breaking Bad—has written his latest opus Pluribus specifically for her. In the Apple TV mind-bender, she plays Carol Sturka, a romance novelist who somehow dodges an alien virus that fuses the rest of humanity into a blissed-out hive mind. The series, which has been marketed as being about “the most miserable person on Earth,” is an end-of-the-world show unlike any other—utopian and dystopian at the same time, with Seehorn’s messy, painfully human performance at the center of it all. When her Better Call Saul co-star and close friend Bob Odenkirk called to find out more about the show (he hadn’t seen it yet), they got into everything, from acting in isolation to the emotional cost of throwing yourself into a role.

———

BOB ODENKIRK: Hi, Rhea.

RHEA SEEHORN: Hey!

ODENKIRK: This is for Interview magazine. Don’t you love these Interview interviews? Did you read them when you were younger?

SEEHORN: Totally. I had a subscription.

ODENKIRK: You did? I never felt I needed to because they were laying around a lot of places in New York.

SEEHORN: I wasn’t that cool. This was Virginia, but I basically thought I was an insider because I had Premiere and Interview. Both large formats.

ODENKIRK: Beautiful, big photography. That’s something that’s lost in our modern world. Everything on your screen is the size of your screen, whereas that old magazine was huge.

SEEHORN: I loved it. Are you at home?

ODENKIRK: I’m at home. Sorry, I’m blowing my nose. It’s cool and gray here. It won’t stay that way, of course. It’s the dead of winter, which means two and a half hours of fog, then swimming and sun. You haven’t spent much time in L.A. in the last year-and-a-half, have you?

SEEHORN: No, I’ve been in your house in Albuquerque.

ODENKIRK: Well, they wanted me to watch three episodes, but I couldn’t make it work.

SEEHORN: You haven’t seen anything?

ODENKIRK: No.

SEEHORN: Are you coming to the premiere?

ODENKIRK: Sure. I can’t fucking wait. I was kind of bummed out by the idea of watching it on my computer. Well, let me start on my questions. So, from what I know of the show, you do a lot alone. True?

SEEHORN: Yes. The thing that happens—the sci-fi element to the whole world—I’m immune to, and it automatically makes me separate from a lot of people.

ODENKIRK: How do you rehearse a scene that you play alone? Is there anything you had to do or think about, especially with no dialogue?

SEEHORN: That’s the other thing: I was not only by myself, but I often had no dialogue.

ODENKIRK: What do you do to get some preparation, or did you not feel the need to?

SEEHORN: I absolutely did. The thoughts that your character is wrestling have to be your scene partner at that moment. Vince does such a great job at not ever making us, the actors, telegraph to the audience what we’re thinking, so I didn’t feel like I had to make sure the audience could follow everything in some kind of simplified way.

ODENKIRK: Do you just sit and contemplate it and write it down? Or do you try to go on set, walk around, and act it out essentially?

SEEHORN: I write it down, do a lot of thinking about it, and then leave space for things to happen in the moment when you get there. That’s what you and I would do on Saul. You do your homework and then you get there, and get thrilled if somebody throws you a curveball.

ODENKIRK: What did you learn about your character in the course of the season that you didn’t know, and maybe even Vince didn’t know, in the first three episodes? And by the way, Rhea, I think this runs after those first episodes so don’t worry about spoilers here.

SEEHORN: Similar to Saul, we were doing one script at a time. Because of the strikes, I was able to have three scripts before we started filming, and I got off book on all three. It was a godsend timewise, because the work starts piling up, and you’re getting the next script, and trying to sleep, and trying to prep. But Vince told me from the beginning that, “I’m not sure exactly what the show is.” I knew what he meant was tone. He really wanted to push tone, this idea of how far can you push a comedic moment and have it live in the same show as a dramatic moment in the same scene earlier. He really wanted to play with changing genre in the middle of a scene. There were things I knew we were going to discover together, and we did. And one of the biggest things about my character was her partner dying, and her grief was very important. It’s a present burden through the whole show, constantly hovering. And my character was almost suicidal to a degree that Vince and I realized we had to pull a back a bit, because where do you go from there?

ODENKIRK: Was there ever anything in the later episodes where you went, “Oh geez, I did not build this character to be this.” Or did it all just organically build on itself without any hiccups?

SEEHORN: Something happens that I know I can’t spoil because it’s a much later episode.

ODENKIRK: The reason I’m interested is because this fascinates me about Vince and his writing—the degree to which he goes, “Jesse was supposed to be killed in the first season of Breaking Bad.”

SEEHORN: My character wasn’t going to be around for Saul.

ODENKIRK: If I could describe what Vince’s dreams and goals in life are, it’s to get himself in a corner and try to figure out a way out of it.

SEEHORN: He literally said that on a podcast I was on with him. “I think I must be a sadist because I like painting myself into a corner and then having to figure out how to get out.” [Laughs]

ODENKIRK: I always balk at the word genius, especially in regards to Vince, because calling him a genius is a way of taking away from how hard he works. It’s a way of saying, “You just have a gift,” when people don’t realize he sweats every second.

SEEHORN: And every word.

ODENKIRK: I write too, and when I’m on my third draft, and I’m like, “That’s enough of that shit! That thing’s done, gold!” It’s like, “This is like a rough draft for him.” We have to discuss the writing, because it’s everything.

SEEHORN: It’s everything. The sets he creates, the people he assembles, and the room he gives you to then challenge yourself is incredible. But the scripts you’re starting with, not enough can be said about that foundation. And as you know, they read like novels. And there’s no typos. And if you do have a question, it’s treated with care and with respect.

ODENKIRK: It’s such an honor to have your critiques and comments treated with respect after the hard work that they’ve put in, that they don’t just go, “Shut the fuck up. We worked so hard on this.” But I want to just point out something that you intimated in your answer a little while ago. This show sounds like it has some comedy in it.

SEEHORN: It’s hilarious sometimes, Bob.

ODENKIRK: It looks like a scary dystopia with a lonely person and tension and a fear that will propel our interest and pull us in. But it’s also got humor all through it.

SEEHORN: Yes. We are absolute idiots when we’re left alone and don’t think anybody’s watching, and Vince really tucked into that. In episode one, he starts the show with a little bit of comedy. I’m doing a book reading and a book signing in a Barnes & Noble, and there’s some funniness there. And then it just goes into this full-out horror movie. It’s all these tropes of things that Vince loves—horror movie tropes, jump scares, zombies, Invasion of the Body Snatchers. But when I was reading it, I was like, “This seems like it’s funny. Is this funny?” And sure enough, it was.

ODENKIRK: That’s so cool. Vince is never overtly political, but Pluribus seems like it might be more of a commentary on how we try to order ourselves as a society. What do you think? I’m sure Vince would never choose a side.

SEEHORN: If you talk to him about themes, he glazes over. He’s not writing themes, and he’s definitely not preaching. But I do know that he has feelings and thoughts about the world that we live in now and its divisiveness, whether it’s politics, or religion, or culture. It’s been very interesting talking to the press about the show. We have people asking, “Is this a commentary on AI?” And Vince was like, “No.” AI existed when Vince first started thinking about the concept about a decade ago but it wasn’t the debate it is now. We were asked, “Is it a commentary on the pandemic? Is it a commentary on religious zealots?” Because there’s a lot of that, too. But like Breaking Bad and Better Call Saul, it’s at its core about human nature. Those are the biggest questions he wanted to ask—what makes us human?

ODENKIRK: Yeah. He’s never going to land on any side. Although I will say, having a lesbian lead character, that’s a big choice for him.

SEEHORN: Even having a female protagonist was a big deal for him. He’s never done that.

ODENKIRK: And asking us to perceive her relationship as deep and true and to believe in that, that’ll actually come off as political too, sadly

SEEHORN: [Laughs] To some people.

ODENKIRK: To half the country. They’ll be like, “What? No way! That can’t be true!” But it’s interesting, based on the trailer, which is all I’ve seen, I thought of the pandemic right away. And I’m sure he would never mean for it to be direct, but as you say, maybe it’s about the divisiveness that we’re all stewing in right now.

SEEHORN: There are big, big questions about isolation and what it means to be alone and this idea of being a misanthrope in the world, which sometimes Vince will say about himself. He really wanted me to psychologically explore the idea of where the breakdown would be if you were absolutely alone, left to your own devices.

ODENKIRK: Wild. Acting, to me, is most rewarding when it feels like a journey, like you have to sort of come back from it.

SEEHORN: What do you mean?

ODENKIRK: Well, you have a hard scene where you’re in the desert and you’re walking around with Mike Ehrmantrout and you’re feeling all these pressures, both physical and environmental, and you have to lose yourself in it. Then you have to come home and be you again. And it’s like you went somewhere, and your own desire to be good, puts you in a different place. I’m sure you spent hours lost in this character, and then you have to remember you’re Rhea Seehorn. And to me, that was the coolest thing about acting, the discovery of that level of journeying. It’s the only reason I understand Daniel Day Lewis, the “I’m Abraham Lincoln for the next three months” thing. Because it’s easier to do that than to try to extract yourself from the character every night and then find your way back in. But you can’t do that when you have to spend 11 months shooting a show. You have to talk to your kids. You have to talk to your partner. You have to live in the world again.

SEEHORN: I know what you mean. Even when we were doing night shoots, and I rented your house there, we’d get home, the sun’s coming up, and I can’t go straight to bed because no matter how much you tell yourself, “I’m Rhea and I’m going to make a hot pocket in the microwave,” my body doesn’t know that what we did was make belief. So if you’ve been running all night or trying to revive your wife and crying your eyes out about it, what it does to your body, that’s all still there. And as you know, you’re also thinking about how the scenes went, and what are the scenes tomorrow. I’m not doing therapy. I don’t believe in going out there and thinking about your dead dog to make yourself cry. I do my “as if” work at home, and then I get there, and I’m putting yourself in the circumstances. But you taught me a valuable lesson during Saul when you had the kind of hours that I then had on Pluribus. You said, “Call your partner and your kids at the meal break, even if it’s only one minute during the day. Because waiting till you’re done to talk to them, it’s not good.” So I did that all the time, no matter how tired I was.

ODENKIRK: How do you depressurize when you’re in Albuquerque? I used to ride my bike for hours. It got easier when we shared a home, because you come home to a social scenario, which was great. And it’s a social scenario that doesn’t mind you obsessing about the show. These are the only people in the world who aren’t like, “Will you shut up about that fucking show?” [Laughs]

SEEHORN: [Laughs] Exactly. I would walk a lot. I wish I had gotten exercise more. I could barely get the prep done and get enough sleep, and then go back to set. But I did tons of jigsaw puzzles and a lot of arts and crafts, because I can’t really shut my brain off.

ODENKIRK: One of the reasons I got into sketch comedy when I was younger is I like thinking about different things over the course of the day. I don’t like having to think about one thing. So I did resent how much Saul took over my life and my brain. But I’m so happy for you. And are you enjoying all the press, or are you sick of it yet?

SEEHORN: I’m into it.

ODENKIRK: Be honest.

SEEHORN: I do!

ODENKIRK: Bullshit!

SEEHORN: I pinch myself. It’s amazing.

SEEHORN: You and I have said a million times, “Somebody could be doing the best work of their life and nobody’s watching it.” We know the gift we get to not just get to do Vince’s scripts, but the fact that Vince has loyal followers and has built a brand that makes people want to watch it. And Apple, spending all this money and believing in the show, and believing in me, and wanting to market it, and journalists that are not sitting there falling asleep because they have to interview me, but telling me that they love the show, and telling me all these things that it brought up in their own head about their own life, and what it means to be human. I’m just like, “Dude, it’s fucking amazing to get to do this for a living.”

ODENKIRK: Right. Well, I think that’s all our time.

SEEHORN: Yep. I was just moving on. That was a great way to end it.

ODENKIRK: Yeah, it was. It was a great final answer.