Before Just Kids: The First Photos of Patti Smith and Robert Mapplethorpe

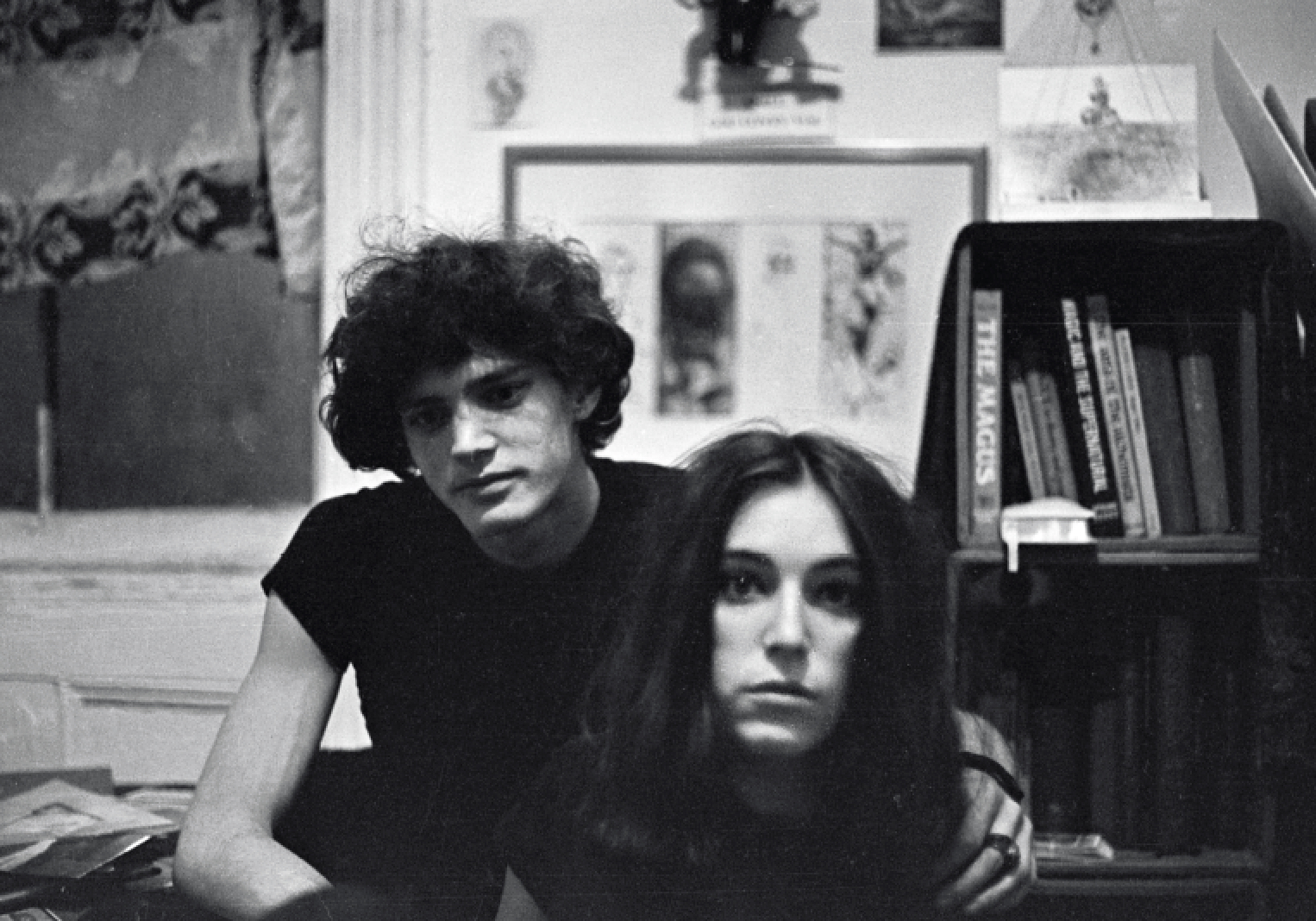

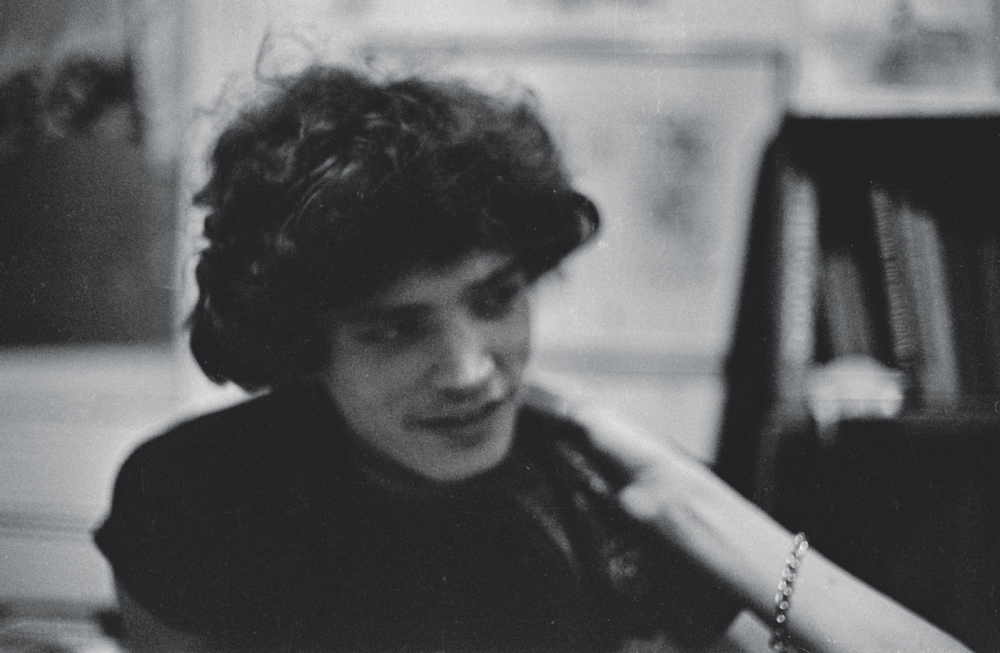

Fifty years ago, Lloyd Ziff loaded half a roll of black and white film (he couldn’t afford more) and, without adjusting his light meter (he didn’t know how), shot a series of intensely intimate, occasionally giddy, relentlessly earnest portraits of a young Robert Mapplethorpe and Patti Smith in a shabby apartment on Hall Street in Brooklyn’s Clinton Hill. Two years ago, he did it again: “They’d gutted the apartment,” the photographer tells me of the time a potential buyer and his girlfriend invited him to see the old haunt after they’d purchased it. “It was nothing like I remembered it when Robert and Patti lived there.” Of course, the couple was nothing like Robert and Patti either, but who could be? When Ziff first shot the legendary pair, before they became the world-renowned photographer and musician that came to embody downtown cool, they were a couple of wide-eyed artists just out of Pratt (Mapplethorpe) and New Jersey (Smith), kicking around in an apartment they could barely afford. But Ziff struck the building’s new owners a bargain: The couple would take him up to the same room where he’d shot Smith and Mapplethorpe, all those years before, and he would take their portraits.

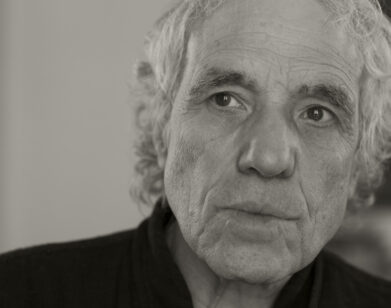

It’s that kind of circularity, paired with the same domestic intimacy, that sets Ziff’s fifty-year-old images—showcased in his new book, the limited release Desire—apart from the endless sheaves of iconic Smith-Mapplethorpe photos. (That, and the simple fact that they’re the first-ever portraits of a pair so beloved by both sides of the camera that the Guggenheim opened a year long Mapplethorpe retrospective heavily featuring his former girlfriend.) Ziff, whose photos have since been published everywhere from Vanity Fair to Rolling Stone to here at Interview, still approaches photography with a kind of base-instinct that seems to bypass technology in favor of something less explicable, but more human. “I liked the sort of magic of photography,” Ziff says. “It wasn’t really about the equipment. It was about your eye.”

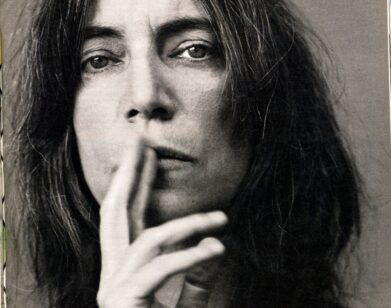

That magic is on full display in Desire. The title is suggestive, but more so of a type of existential longing than a physical one. Desire, Lloyd tells me, is a word straight out of Patti’s mouth; in her song “Piss Factory,” Smith sings about her nearly carnal urge to get on a train, to go to New York City, to be a big star. Knowingly, Ziff’s book flanks Robert and Patti with early shots he took around the city, setting the couple firmly into the setting that defined them, and that they in turn defined. The kind of desire that the book telegraphs implies both a journey and a destination, showing us a couple who were both desperate to get going and had somehow already arrived. Fifty years ago, Patti and Robert had already hopped on the train. And here, in a return to the first-ever portraits of the pair together, they’re looking right back.

———

JADIE STILLWELL: How did you first start taking photos?

LLOYD ZIFF: I was a Graphic Arts major at Pratt, where I met Robert. I never really thought anything about photography. I thought it was complicated. Light meters and lights—I just didn’t know anything about it. I was a good illustrator and a good type designer and I really liked reproduction. But, by chance, I had a roommate my last year at Pratt who had a Rollei, and we went walking around New York with it and he said, “Hey, look, you can take these pictures with it if you like.” And I enjoyed it. He told me you didn’t really need a light meter, and that we could develop the film in the closet in our apartment.

I liked the sort of magic of it. I still do. But my last semester at Pratt, I took a photography course. It turned out to be the most important class I took at Pratt. I had a great professor, Arthur Freed. He taught me that it wasn’t really about the equipment, it was about your eye. Every week, we brought in pictures from magazines that we either liked or disliked and we put them on the wall and discussed what made them work or not work. He pointed out a lesson that I still find, 50 plus years later, incredibly valuable: that it’s much easier to take a mean picture, an unflattering picture of someone, than it is take a loving, sweet picture of someone. I think about that all the time because nobody wants to make people look bad.

I used to watch Arthur print in his dark room on the weekends, and I soon realized that I really loved photography, but I thought of it as an art form for myself. It wasn’t something that I thought I could make a living at, because like I said, I’m not mechanically inclined and I never learned how to use a light meter. I graduated Pratt with a degree in graphic design, so that’s where I figured I’d make my career. And I did. I had a really nice 35 year career as a graphic designer working for magazines that I really respected. I was Art Director of Rolling Stone. I was the first Art Director of Vanity Fair. I helped Harry Evans invent Condé Nast Traveler. I was really doing work that I was very proud of. Occasionally I could sneak my own photographs into the magazine, but mostly my photographs were for me. Nobody critiqued them. Nobody was buying them.

STILLWELL: Because they were personal?

ZIFF: Exactly, it was personal art. I kept them under the bed and showed them to friends. I did that until the end of the 20th century. I like saying that. It sounds so mature. And then I had a heart attack and I thought, I’ve done everything I wanted to do as a graphic designer. So, I decided at the beginning of the century that it was time to take the pictures out from under the bed and show them to people. Because I had such a visible job and had interesting contacts, I could get a little bit of work as a photographer for magazines. In fact, I did a couple of things for Interview, and I went to galleries and the response was pretty good. I had a couple of one-man shows in New York, one in Los Angeles last year, one in Paris. I stopped designing as soon as I started photography full-time because people wouldn’t take me seriously as a photographer if I was still doing book covers or whatever.

STILLWELL: The pictures with Robert and Patti feel very personal. That definitely comes across.

ZIFF: Jadie, all my pictures are very personal. Even the ones I did on assignment were personal, and there aren’t that many. But I think of all my pictures as personal. That’s the truth. I never wanted to learn how to use a studio or lights or anything like that.

STILLWELL: Do you remember how you met Robert?

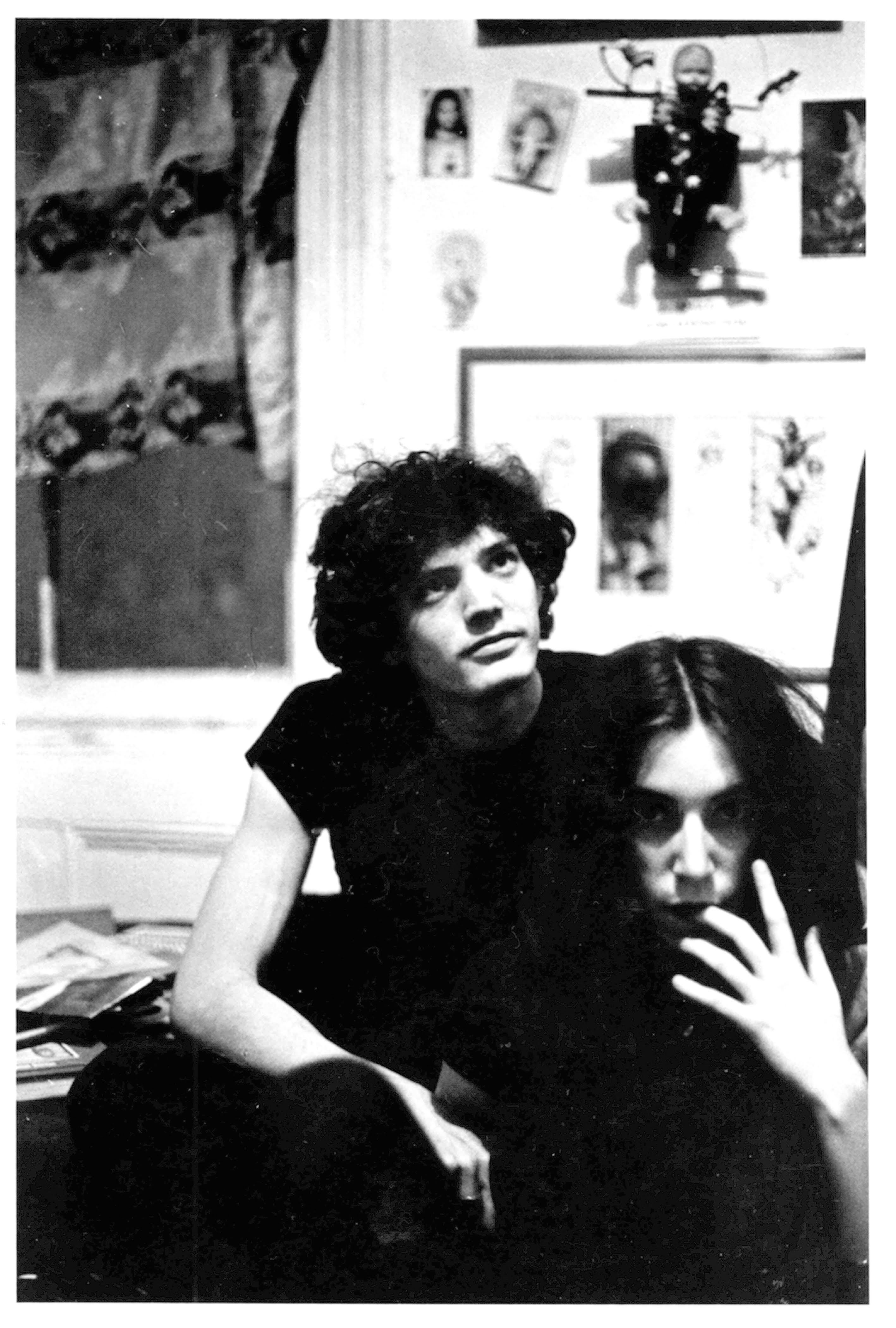

ZIFF: When I was going to Pratt, Robert and I were in the same class and we were friends. We weren’t very close friends, but we were close enough. One early evening, I saw Robert and Patti crossing the street. We both lived in very cheap small apartments near Pratt in Fort Greene. And I was just learning to take pictures then, and Robert and Patti were so beautiful and so intense.

STILLWELL: Had you known Patti at all before?

ZIFF: Well, I knew her through Robert. She was always around. I asked them if I could come by one afternoon and I’d do some portraits of them and they were up for it. This is sometime in the early summer of ’68. I went to their place. We just did the portraits. They really were happy to have portraits done together and separately. Unfortunately, we were also poor. I only got a half a roll of film, even though film was pretty cheap. I had just graduated and I didn’t really have hardly any money and certainly Robert and Patti didn’t. So I shot a half a roll of film.

STILLWELL: Is that why you chose to include the contact sheets in the book? To give an idea of how spontaneous it was and how limited your resources were?

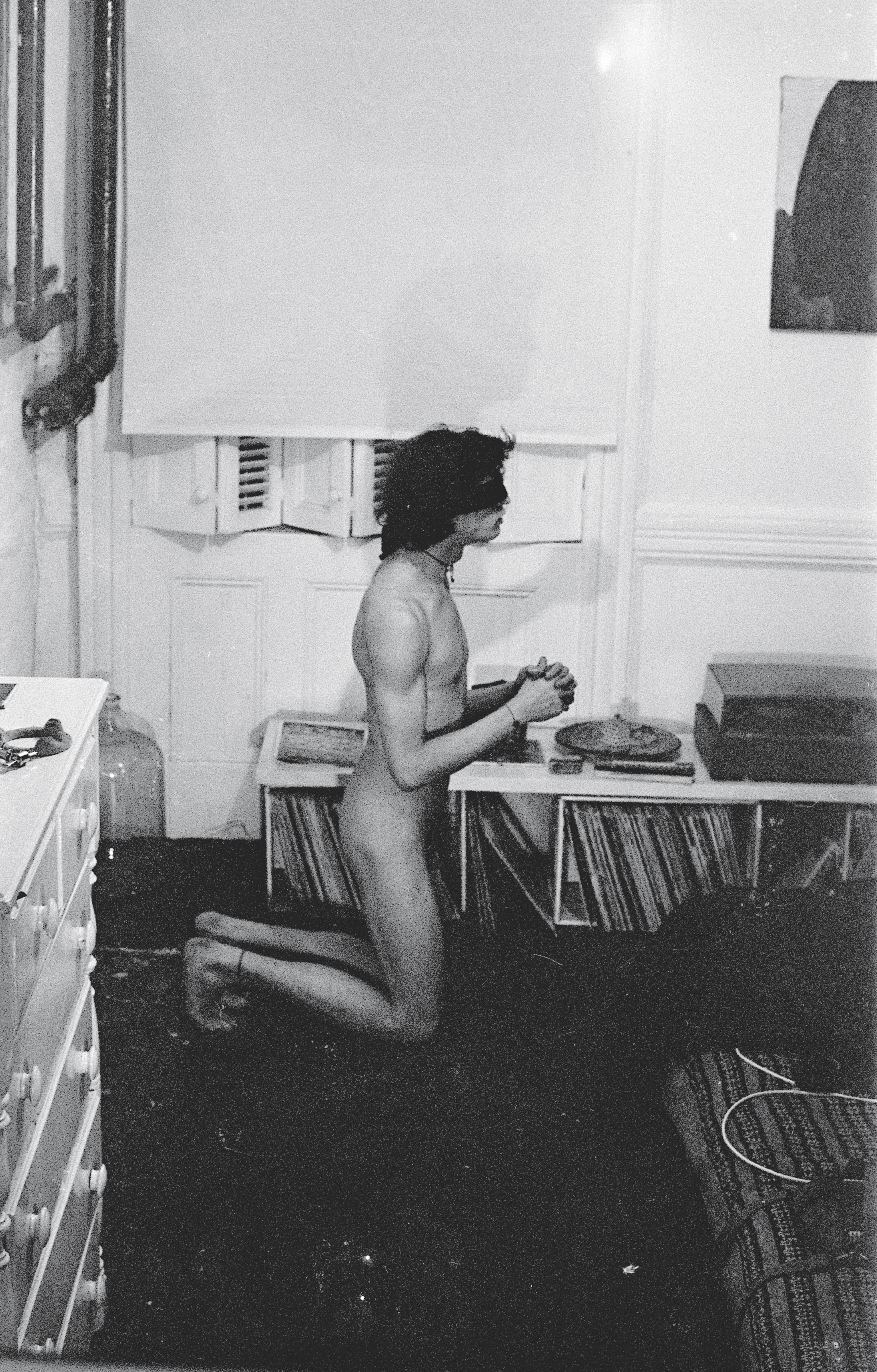

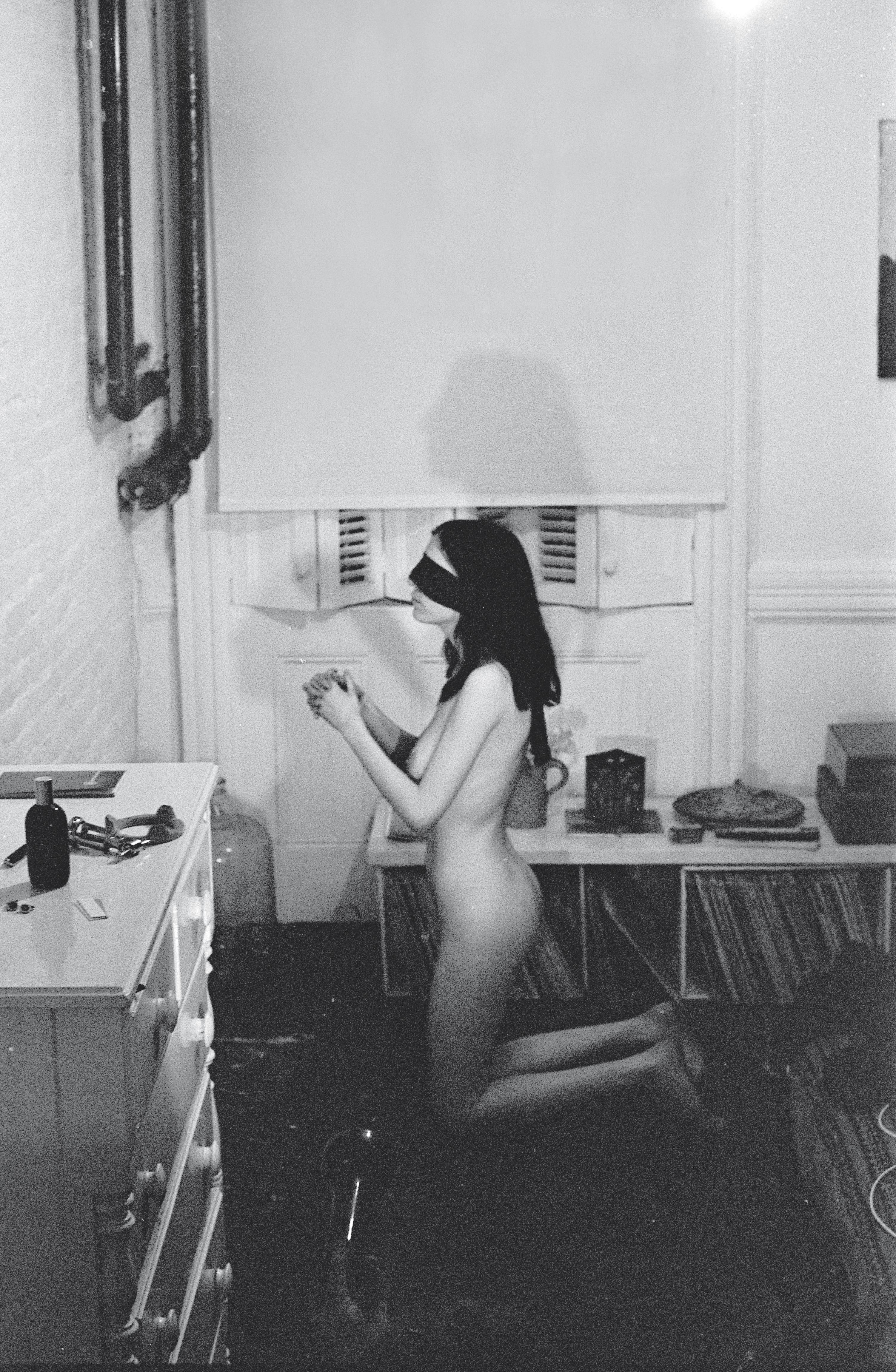

ZIFF: Yeah, exactly. And also you can see that there’s light leak on some of the frames because I developed them in my closet. I’m sure I gave them a couple of prints or whatever, I don’t remember. It was a long time ago. But a year later, we were doing better. I was designing album covers in CBS. I moved to a basement apartment on Charles Street in the West Village. Robert and Patti moved to the Chelsea Hotel. Robert called me and asked me if I would do some nude portraits of him and Patti that he wanted to silhouette and use for a little animated film that he wanted to make. And I said, sure. They came over to my place. They just took off their clothes and we set a light up, clamped it to a chair, and we did the pictures. There was no sexuality at all. We weren’t embarrassed. It was the late ’60s.

![]()

STILLWELL: Are those poses something that Robert chose? Particularly the ones where they’re kneeling?

ZIFF: The poses were totally Robert’s. He knew what he wanted, the film he wanted to make. He knew what he needed. He wanted whatever I shot. He told me, “I’m going to kneel. I’m going to be blindfolded. I’m going to put my arms out.” Really, he just trusted me. That’s the reason that he asked me to do it. In retrospect, it’s very interesting to me. We became closer as the years went by. I was friends with Robert until he died, and I enjoyed commissioning work from him for Vanity Fair and Traveler and House & Garden, too. Not because he needed the money, but because he became such a great photographer and I liked working with him.

STILLWELL: Was that shoot the beginning of your friendship?

ZIFF: It was part of it. What interests me most about that time is that both Robert and I were gay, but neither one of us ever talked about it, I don’t think, even to ourselves. I mean, it was the late ’60s, and people, I must say, were flamboyantly out and trying to figure out how to deal with their confusion of their own sexuality. At least I was. I think Robert was, too. And so, although we sort of had this unspoken recognition of each other, we never really talked about it. We were just not talking about what was going on with ourselves because we didn’t understand it. Later, in the mid ’70s when I was living in LA, Robert came to LA and we hung out a bit together. And then when I was in New York on business, he took me on a tour of the gay bars on the West Side, by the pawnshops and stuff. But by then we could be open with each other. I did these pictures, and I gave them to Robert and they obviously were very personal and I never did anything with them. They were basically in my drawer for about 50 years.

STILLWELL: Why didn’t you ever do anything with them?

ZIFF: Because they were my friends and, I think that as they became more and more renowned, I just thought it’s not really something that I wanted to do. Where would I publish them? It didn’t seem right to me. They were too personal. But then in 2009, Patti called me. By this time, she was living in New York and she was back recording after her husband passed away. We saw each other on occasion at openings or readings that she gave or concerts that she gave and I’d always say hello and we’d hug, but I can’t say we were ever really friendly because she was in a whole other world. But we do have some mutual friends and she called me and told me she was writing her story of her life with Robert, which eventually became Just Kids, and asked could she use a couple of the photographs that we did on Hall Street in ’68, the portraits.

And I said, “Of course, yeah, Patti, which ones do you want? I’ll send you a selection.” And she chose the ones she wanted. They’re in the first edition of Just Kids. And then she said, “These are the first portraits ever done of the two of us together.” So that made me really happy. But the surprise of that book is she also wrote about the nude pictures. I couldn’t imagine why she would use my name and write about the naked pictures. They’re not part of my story really, or they weren’t. But she says that Robert wanted to make a movie using nude pictures and he asked me to photograph them. She didn’t like the pictures that much and he lost interest in the movie and she suggested to him that if he wanted to take pictures, why didn’t he learn to do it himself. And I thought, well, that’s an interesting point.

STILLWELL: How did Patti using some pictures in Just Kids eventually turn into your book?

ZIFF: A couple years ago, Nick Groarke, the English publisher, said, “I’d like to do a book of your pictures.” And I thought, “There aren’t really enough.” I didn’t really shoot enough to do a book, but then he called me and he was really charming on the phone. So I said, “Well, you’re welcome to talk to me about it.” He came to New York and came out to my home in Orient Point and we looked the contacts and the negatives and all of my pictures of that period in New York. He thought he could figure out a book. I said, “I don’t want to have to design it, you know? If you want to design it and I don’t have work very hard on it, you’re welcome to have access to the negatives, to the prints and if I like it, we’ll do it.” We worked on it for two years. It was a really strong collaboration. If I didn’t agree with something he was doing, he’d change it and vice versa. It was his idea to put the pictures in the front and the back of my New York pictures from that period.

STILLWELL: Those photos are great, even though they’re not explicitly related to Patti and Robert. Why did you choose to include them?

ZIFF: It’s a lovely preface to the book. It sort of places it in a particular time.

STILLWELL: Do you have a shot or an image in the book that stands out to you?

ZIFF: I like this one picture of them together a lot. Patti has one finger in her mouth and her hand up to her face, but she’s almost biting a nail. I particularly liked that one because it gives a sense of the room. You could see Robert’s drawings and a little, it looks like a sculpture on the wall behind them.

STILLWELL: I also wanted to ask about the title, Desire. What’s behind that name?

ZIFF: We thought a long time about what to call the book. Patti wrote a song. It’s one of the very first recordings she did in the early ’70s and it’s called “Piss Factory.” She talked about working in her late teens in a factory in New Jersey. I forget what they were making, but it sounds like hell, and at the end of the song she says, and I have to paraphrase, “I’m going to get out of here and go to New York and be a big star because I got something to hide and it’s called desire.”

I thought that’s really important because you can sort of see it, especially in the ’68 pictures. She’s young, she’s beautiful, she’s intense, but she’s smart and driven. I don’t think she had any idea that she’d be a recording artist, but she was already an artist. She was making art, painting, drawing, writing. She was on that road, and it was a straight road. I mean, it had lots of origins, but it always included the idea of being an artist, and Robert also. I think that’s why I wanted to call it desire because, I mean, everybody who went to art school wanted to be an artist and she wasn’t even going to art school. She was living with Robert who was going to art school. But they already were artists. You could feel it.

STILLWELL: That drive and intensity comes across in the photos, too. She’s so often looking right into the camera.

ZIFF: That’s one of the reasons I really wanted to take the pictures, to shoot them. I was shooting my other friends at the same time because who are you going to shoot when you’re young and learning to take pictures? You shoot your friends. And they were all art students. A lot of the pictures are similar in feeling, but the pictures of Robert…God, it was Robert and Patti. 50 years later, they still zoom out at you, you know?

STILLWELL: Why do you think that is? Is there something inherent that sets them apart as people or as subjects?

ZIFF: I think it’s their particular intensity of feeling who they are. I mean, you can see it in the pictures. They wanted to have their portrait taken.