LIT

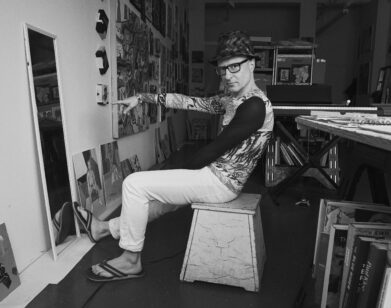

Lucy Sante on Kafka, Communism, and Comme des Garçons

I recently met up with the erudite and self-possessed Lucy Sante at Washington Square Diner during one of the first snows in New York. After eating eggs and toast, we reminisced about white winters and the obvious lay between us: the changing shape of the world’s greatest city. Few blizzards grace us anymore, and Eric Adams is no help at all either. As we walked around, Sante pointed out buildings with ghostly histories, urging me to see the Jacques Rivette film playing at IFC, and joked about how she used to return here and ironically recite Jack Kerouac: “I did everything with that great mad joy you get when you return to New York City.”

We’d met up to discuss her latest book, I Heard Her Call My Name, a memoir about transition. It marks her first foray into long-form writing about the subject, though it expands upon an earlier Vanity Fair article (which was accompanied by a six-hour Ryan McGinley photoshoot). Sante remains difficult to pin down, partly by design. In her new book, she writes, “Transitioning really makes you admire the beauty of the dialectic.” Sante criss-crosses her subjects, from bohemia to the effects of estrogen, never settling on this or that but rather unspooling the contents of her mind by wandering through a labyrinth of “chance and intuition.” Speaking to her, I encountered a similar whirl of literary and geographic exploration—a desire to explain herself fully and be frank about things she’d previously held back on. Shortly before the publication of her memoir, we discussed her relationship to Japanese fashion, iconoclasts like Patti Smith and Kathy Acker, her time as a critic, and which trans writers she admires most. She loves Emily Zhou’s Girlfriends and Paul Preciado, she said, but found Detransiton, Baby to be “a Park Slope novel.”

———

GRACE BYRON: I just came back from a Christmas trip home, not my first as a trans woman in Indiana, but the first in quite a while. My boyfriend, who is also trans, came with me. It was a curious time but I was able to go back to my favorite record store, one of the few places that felt like “culture.” I got a Yeah Yeah Yeahs shirt there many moons ago and a Melvins button. I wonder what role music has played in your own cultural education?

LUCY SANTE: Yes, for me it was Scotti’s Record Store in Summit NJ, where a grid in the front window showed you the hot 45s, often the first time I’d hear of something that became a cornerstone for me. And in the 60s, there was radio and giveaway papers, too. I’m deeply into the 60s right now because of the book I’m working on. The backstory is, after Lou Reed died I wrote a little obit for the New Yorker blog, whereupon Andrew Wylie, who was Lou’s agent but not mine, decided I should be his biographer. Before I had time to think, I found myself with a contract. I knew right away I didn’t want to do it, but there was all this money. No disrespect to Lou, but while he was huge to me in my youth and I revere many things he did, he also cranked out a lot of bullshit, not to mention that he’s been done over and over already, and Will Hermes’s book was always going to be the best, and anyway I never want to be anybody’s biographer. It’s a master-servant relationship even if they’re dead. But transitioning came to my rescue. My agent, Joy Harris, and I proposed a swap: this memoir and another book, which it was decided had to have a Lou link, so it’s going to be more or less The Velvet Underground in their time, which I’ve always wanted to write about. So I’ve been immersed in 60s music, and also more or less current artists who fit in with my 60s preoccupation: PJ Harvey, Belle & Sebastian, Myriam Gendron, Cat Power, Damon & Naomi.

BYRON: Film plays a heavy role in your new memoir as well. I think it’s interesting to think about the many ways gender and culture criss-cross. What films inspire and haunt you?

SANTE: My gender cornerstone in films is the work of Jacques Rivette, whose films all had female protagonists. I experienced them directly as transgender works because Rivette was so clearly pouring himself into the heroine or heroines, thoughe never addressed the question of gender in print.) And when Bernadette Lafont and Geraldine Chaplin don pirate drag to enact Jacobean revenge drama in Noroît, or Bulle Ogier and Juliet Berto zip through multiple costume changes in the seedy-underbelly in Duelle, I just lose my mind.

BYRON: Are there contemporary filmmakers you admire?

SANTE: I love P. T. Anderson. I’ve spent the past year defending Licorice Pizza. I love Killers of the Flower Moon and Silence, the Scorsese film no one else appears to have seen. I love Claire Denis, of course. I deeply love Kaurismaki, even if Fallen Leaves isn’t quite up there with his best. I love Park Chan-Wook. I love Almodóvar, whose pictures I watch like eating candy. I love the Dardenne brothers, whose films are all set in my childhood terrain. I was very surprised to find that I really, really liked Maestro.

BYRON: You mention in the book some of the women that inspired you. I’d love to hear how “discovering” certain women allowed you access to a wider array of femininities.

SANTE: In 1975, when I was 21, I found a copy of The Childlike Life of the Black Tarantula by The Black Tarantula on a rack at the old Eighth Street Bookshop and I was immediately smitten.t took me a while to notice Kathy Acker’s name on the copyright page. Coming a bit after Patti [Smith], this was the second time I’d been bowled over by the literary power of a woman in my age bracket and they weren’t doing anything the way men were. Most of the women writers others were reading came from the British bourgeois literary tradition, and although I loved the Brontës and Mary Shelley, I couldn’t deal with the Victorians or even beyond, for class reasons. So, as I always do in different contexts, I began picking up strays: Mary Butts, Christina Stead, Marguerite Young, Ann Petry, Djuna Barnes, Joan Murray, Janet Flanner, Patricia Highsmith, Renata Adler, Veronica Geng, these in addition to those named in the book.

BYRON: Did you ever meet Kathy?

SANTE: I met her just a couple of times. I didn’t say much because I had a massive crush and was all shy fangirl. I published her in both my zines, Rongwrong, which never came out, and Stranded. I loved her voice, both in the room and on the page, and I loved that she was hijacking these famous books. She was the one great writer of the punk moment. The image I carry around is something I either heard or read: Kathy, wearing a Farrah Fawcett t-shirt with the eyes burned out, standing on the sidewalk hurling abuse at people leaving Studio 54.

BYRON: There’s also an underside to cultural production. You once wrote: “We thought the music would change the world, and we were correct except in the matter of specifics.” Can you talk to me about what that quote means for you?

SANTE: Well, hard as it may be to believe now, in the late 60s many people including me believed that rock music was the cultural wedge that was going to force open a worldwide revolution in the name of love and truth. Woodstock killed that for me, though I wasn’t there. I hadn’t considered complacent self-congratulation to be a proper revolutionary attitude. Anyway, capital effectively crushed the utopian impulse, but it died hard. For me, it wasn’t about message lyrics but about the riddims. Dancing to Jamaican music especially made me feel as if the promised land was nigh. But by about 1984, when that line is set, it became inescapable that our little scene, radiating out from CBGB, had gone from obscurity to a powerful tourist magnet and buck-generator for an army of hustlers. It’s part of what remade my old East Village neighborhood. The music brought in not revolution but high-power landlordism.

BYRON: Was there a big shift from the last book, Nineteen Reservoirs, to this one?

SANTE: A book about the place that surrounds me immediately preceding a book about the deepest part of me doesn’t seem like such a stretch. I had long carried around a notion to one day write a memoir called “My Education,” though it’s a title used by many, about all the people and circumstances I learned from and a lot of that seems to have leaked into this book. I suddenly realized that I do know the mechanics of my transition. It happened the moment I took it into my head to pass all the old photos of me through FaceApp. Finding them involved a massive treasure hunt from basement to attic, going through albums and biscuit tins and shopping bags, and thus became a project, and I’m always susceptible to projects. And what that did was break through the strict, self-imposed time limit I always had on my ideation, fearing the one-way trip it was bound to be. So it’s conceivable that had such a set of circumstances happened earlier, I might have transitioned earlier. Not much earlier, though, maybe 10 years at most; before that, it would have been materially and psychologically impossible. I would simply have lost my shit and maybe killed myself.

BYRON: Was Jan Morris an influence?

SANTE: Jan Morris, I was prejudiced against by the visuals: she had merely turned into a tweed-suit and sensible-shoes sort of Englishwoman. I hated her hair!

BYRON: I feel like I have to ask a classic New York question. Do you have a favorite diner?

SANTE: I’d have to say my favorite diner is B&H.

BYRON: A lot of trans women have worked at the Strand, including you and me both, as well as Imogen Binnie and Zefyr Lisowski. It feels almost like a rite of passage. What was it like?

SANTE: I was always fucking up. I was always coming in late. It was the No Wave. I had a front row view. We unionized successfully. I made a lot of friends there, some of whom I still know.

BYRON: How do you feel about unions now?

SANTE: I’ve been in about three or four unions. Unions are absolutely necessary. My father worked in a place that was family-owned and never got a pension. He worked there for 35 years and did not get a pension. It was paternalistic. I’m a strong believer in unions, but they can be very dangerous.

BYRON: How so?

SANTE: The classic textbook example is May ‘68 in France. Between them and the Communist Party, they broke the back of the revolution.

BYRON: You’ve described yourself as a Communist. Do you still?

SANTE: A Libertarian Communist. It’s almost a paradox. I don’t have a political program worked out, but I believe in the redistribution of wealth. It’s funny, because I’m Libertarian in some ways and authoritarian in others. Right now, with the housing crisis in New York, I’d be perfectly okay with the seizure of unoccupied property. On the other hand, I’m sort of resistant to any form of authority.

BYRON: What are your thoughts on trans literature in general? In your new memoir, you write about reading a lot of the major trans writers.

SANTE: I really admire Nevada. That was the first book I read that I thought, “Now we’re getting into serious trans literature.” I had read Detransition, Baby before that. She [Torrey Peters] is a great writer of prose, but she uses this skill she has to turn out a fucking Park Slope novel. I mean, it’s trans—but it’s a fucking Park Slope novel.

BYRON: Have you read Hannah Baer?

SANTE: That’s way too insider baseball for me. I’m not in the in-crowd. Another one I liked is Emily Zhou’s Girlfriends. That I thought was really cool. It’s good writing, deftly observed, with well-chosen language. I’ve admired Andrea Long Chu since the beginning. I feel a deep tie there because she’s perverse. She’s not going to be following any party line. I like Paul Preciado very much. One image I had in my head writing my book was Kafka’s “A Report for An Academy.” One line I had in my head was “You show me the honour of calling upon me to submit a report to the Academy concerning my previous life as an ape.” I thought, can I use this? Then I bought Preciado’s book and he did that in his book Can the Monster Speak? The other book I really, really enjoyed were the memoirs of April Ashley. Honest trans memoirs don’t get a lot of traction with me, but funny ones do.

BYRON: In the book, you write about an intergenerational friendship with a trans woman named Leor Miller. Can you talk about what she means to you and how you met?

SANTE: I met her by way of the death of a mutual friend, her teacher, my friend Barbara Ess. Me and Leor clicked immediately. She was really, really important during my first year of transition. I would drive up to Hudson and we would hang out in public. Her lesson was to just sail through things, ignore what’s coming from the sides. Absolute self-confidence. I don’t see her as much anymore because first she moved to the city and now she’s at Yale Photo.

BYRON: You also write about the stereotypes of trans women who wear frumpy florals and those who wear Japanese designers. Who are your favorite designers?

SANTE: It’s interesting because I first went to the female impersonator store and then bought a ton of shit on Amazon and within a couple of weeks I was buying Comme des Garçons. I love Comme des Garçons. Not all Japanese fashion stuff is appropriate for me at all. That all happened within the first few months of transition. Now I’m more concerned with “Oh, I don’t have anything of that length or that color.” It’s not about exploring. It’s about building a profile. I have a pretty good sense of what my style is at this point. I haven’t gone to buy Japanese clothes on Ebay in two-and-a-half years. I buy less expensive things and I have my uniform. I have a range of cardigans and many of these shirts and a full range of these skirts in a variety of colors.

BYRON: How did you come to structure the book?

SANTE: That’s a lot of ditch-digging that I do not feel like doing. Furthermore, I was most concerned with explaining myself. It’s a long explanation of myself to the world. I wondered about structure when the book was just like, a fetus floating in my head. The minute I started thinking about it seriously, I realized it was the old suspense novel trick. They’re not exactly cliffhangers, but it’s cutting the narrative off and starting another one. It’s purely Pavlovian. It was probably the easiest book I wrote. It took me less than two months.

BYRON: You’ve talked about seeing Patti Smith live and going home and shaving. How do you reflect on that moment now, as either a prophecy or a pre-transition moment?

SANTE: Patti set off a revolution in my head. That’s definitely when it hit me. The Feast of Epiphany was yesterday.

BYRON: Did you celebrate?

SANTE: [Shakes head] Well, last year we were in Paris and we had Three King’s cake.