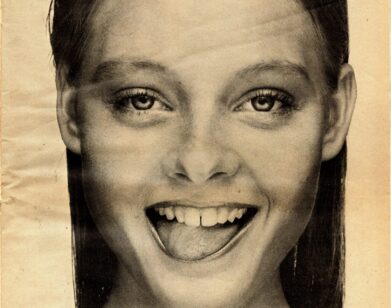

PARADIS ICONS

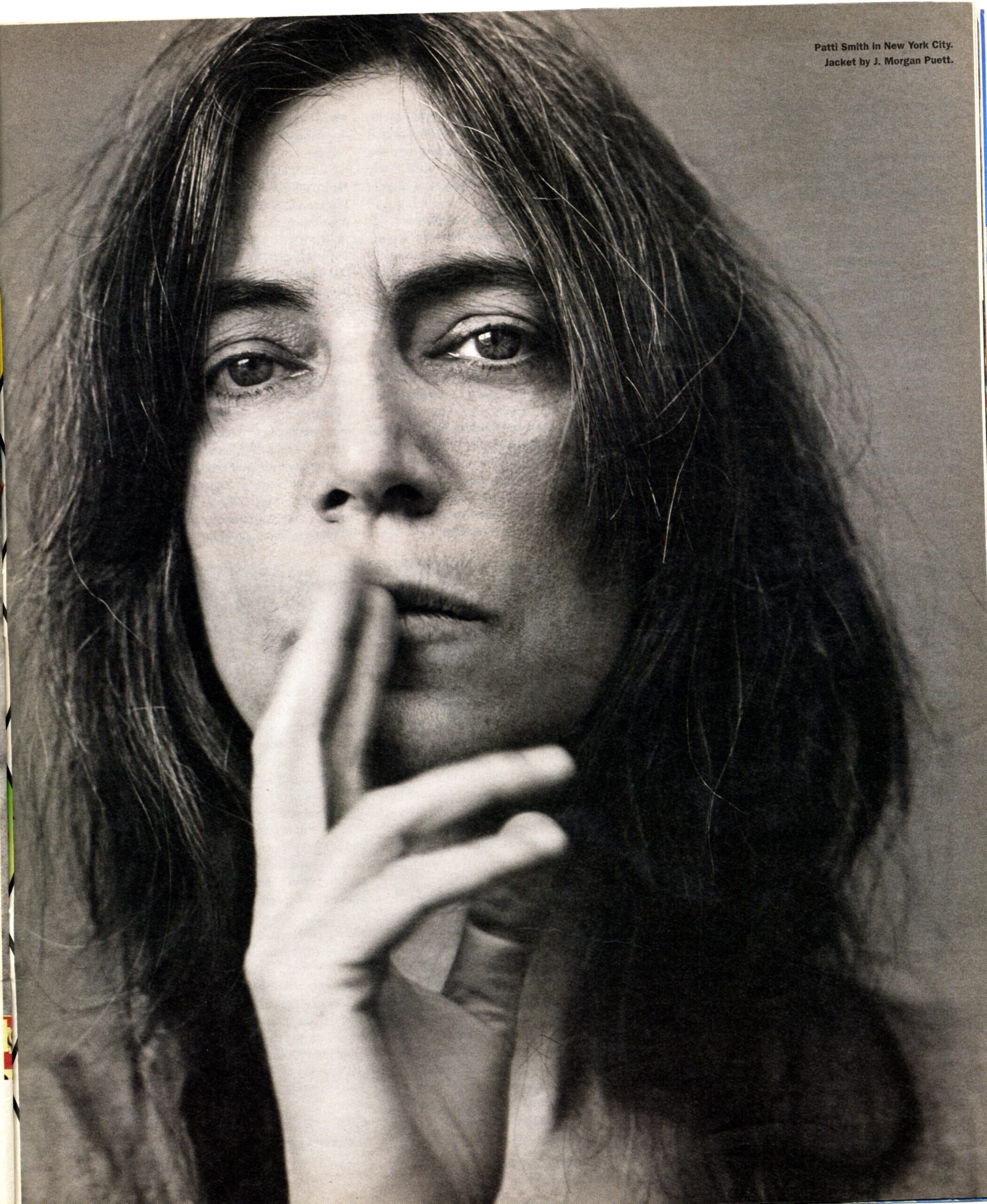

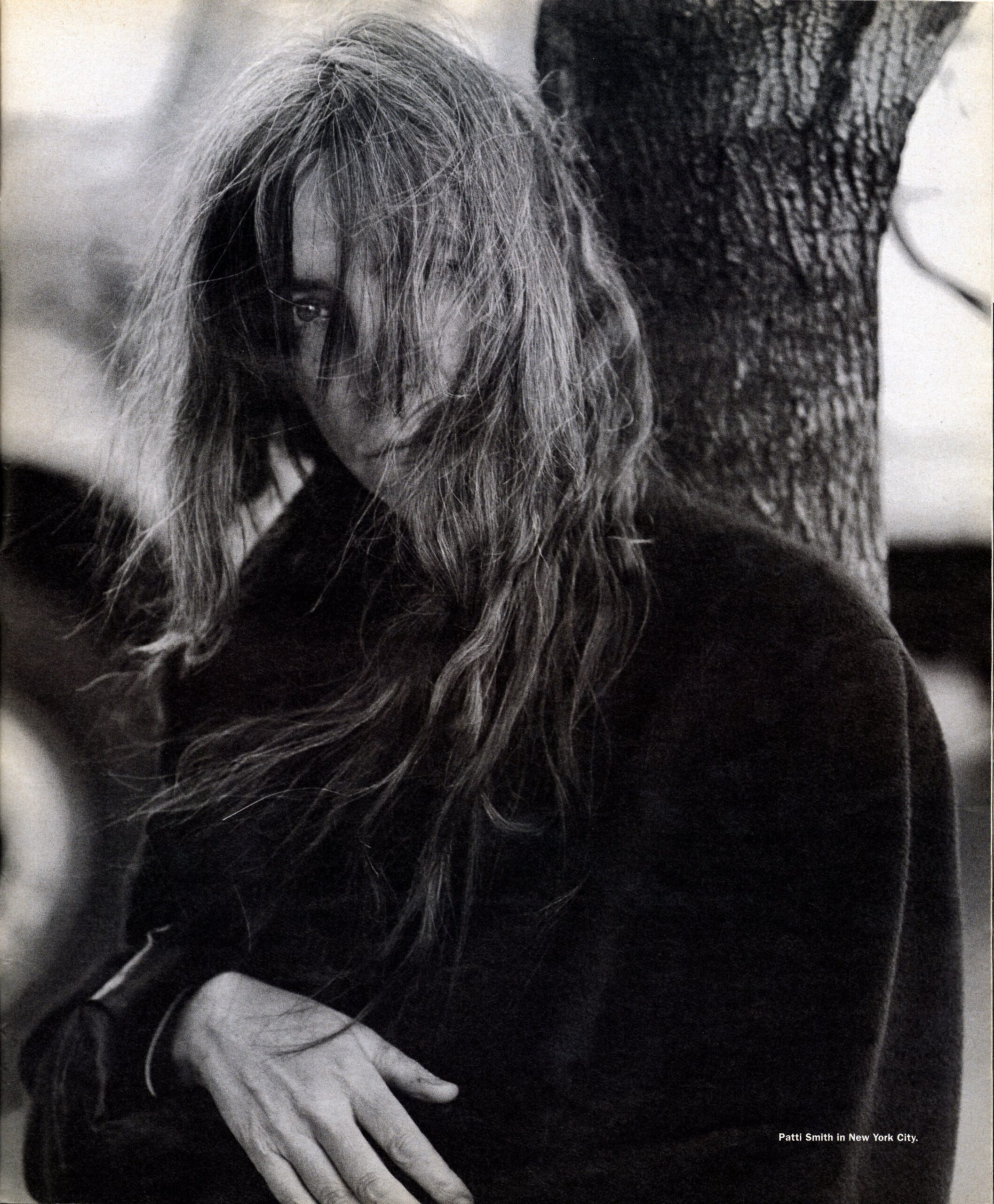

A Taste of Paradis: Patti Smith, in Conversation with Ingrid Sischy

Over its 258-year history, Hennessy has pioneered and elevated the art of cognac, a spirit fit for kings and queens.

Interview hasn’t been around quite as long – just 54 years – but we like to think we, too, have curated conversations and photography that aspire to a similar level of elegance and sophistication. In honor of Hennessy’s storied Paradis marque, we poured through the Interview archives to recirculate conversations with personalities, entertainers, and icons who personify the brand’s spirit of refinement, grandeur, and artistry. Today, we revisit the June 1996 issue, in which the ethereal Patti Smith sat down with our then-EIC Ingrid Sischy to discuss fame, meeting Mapplethorpe, and New York City.

———

INGRID SISCHY: There are so many places we could take off from. There’s your new record, Gone Again [Arista]. There’s your new book, The Coral Sea. There’s the fact that audiences have been responding with immense feel to the occasional performances that you and your floating band have been doing over the last year. Each time you’ve played, the response from both the crowds and the critics has made it clear that the hunger to see and hear you is huge. And then, of course, there’s the space of years where you weren’t a public figure and instead chose to be private. There are the reasons why you made that choice, which I want to talk about later. Then there’s what happened in your life during the time that you were out of the limelight, and what you learned from that. Whenever I’ve thought of you, Patti, l’ve always known that for you, being a human being and being a real artist are much more important that being a famous star. I think everyone thinks of you that way, whether they know you or not. It’s not a matter of some spin that’s been put on you, it’s everything that you’ve done and been. So let’s begin with how that started. What was it that got you on the road to becoming a writer?

PATTI SMITH: Well, there were a couple of things. One was a little book my mother gave pie when I was about three called Silver Pennies, which was filled with poems about elves and fairies. That sort of seduced me. And then there was Robert Louis Stevenson’s A Child’s Garden of Verses. That book deeply seduced me, especially the poem called “The Land of Nod.” I hungered for it. Then I read Little Women, and of course, like a lot of really young girls, I was very taken with Jo—Jo being the writer and the misfit. I started to want to become a writer. But what would I write? My first daydreams or aspirations were that I would write the kinds of things that Robert Louis Stevenson and Rudyard Kipling wrote. And as a teenager, I also imagined myself a jazz poet—not a very good one. I’d just listen to Coltrane and then write poetry. When I discovered the poetry of Rimbaud, I actually stopped writing for a while because I felt like I’d found the ultimate language.

IS: How did you discover Rimbaud?

PS: I found him in a Philadelphia bus depot when I was sixteen. I remember seeing a copy of Illuminations for sale on a table of used books. Of course, illuminations is a great word, but what I was really taken by was the cover. It was a beautiful picture of Rimbaud. That’s why I got the book. When I opened it up, I didn’t really understand it. It didn’t compute. But still, somehow, I knew this was the perfect language. It looked like it glittered. I knew someday I would decipher it. So I carried the book around with me.

IS: It’s amazing how we know something is profound sometimes before we even understand why. Isn’t it?

PS: Yes. And there were other things, too, that made me know writing was a beautiful thing. Bob Dylan was developing his thing his exploration of language also made me want to write. But I didn’t think I was very good at it. In fact, I thought my calling was to be a painter.

IS: Did you go to college for that?

PS: I went to Glassboro State Teacher’s College in New Jersey, which was about all I could afford because I put myself through school. I left there, after three years, in 1967. New Jersey was no place for me and I wanted to go to New York. The only people I knew in the New York area went to college at Pratt in Brooklyn, so I went to find them. When I got to the one address I had, it turned out my friend had moved. Someone told me to ask the person who was staying in the room now if he knew where my friend had gone. That’s how I met Robert Mapplethorpe. The door was open and I went in and he was sleeping. I stood over him, looking down at him, and he looked up at me and smiled. That was our first encounter—and he led me to my friends. I moved to Brooklyn and lived with Robert while he went to Pratt. We worked all the time. I just drew and drew, and Robert would ask his professors to look at my work even though I wasn’t a student there.

IS: Whenever I’ve seen the things you guys made back then, I’ve been struck by the aura that they have. But tell me, did you feel pulled in two directions during those days, in terms of the literary versus the visual? Often the prevailing wisdom is that we’re supposed to choose between one thing and another. Can you believe how stupid that is? It seems to me that these labels and slots that people get packaged into are so artificial, so limiting. Your triumph over all that is another reason I wanted to talk to you. For instance, your new record cannot be slotted. But your work’s always been about the way things connect. Let’s keep talking about how this stream of connections began.

PS: I think I’m constantly in a state of adjustment. When I was younger, I also dreamed of being an opera singer, simply because of Maria Calas. I used to daydream about being like her, but I didn’t do anything about it. The way all these things commingled and I wound up doing what I do seems to me like a piece of calligraphy. It’s all intertwined. Somehow I started introducing writing into my drawings, and after a time, the language took over and I started getting very involved with the handwriting and then the look of the handwriting. The language literally just spilled onto the wall and got physical. Finally, it reached the point where I was no longer content just to write the language. Meanwhile, Robert was encouraging me to read my poetry. He knew poets like Jim Carroll and people like that who said poets should read their poetry, not just write it. It wasn’t very easy though, in 1970, to find a place to read poetry. The scene was very cliquish and closed and I didn’t know anybody in it. Robert perceived the St. Marks Poetry Project as the best place, and [laughs] he always believed we should go to the top. He talked to Gerard Malanga about the possibility of my reading there, and got me a date.

Is: Describe the first time.

PS: Before I did it, I had checked out poetry readings and thought they were really boring. I wanted to do something different. By then I had read every available piece about Rimbaud written in English. No one was more irreverent about other poets while they read than he was, and he always let it be known if he thought the poets stunk or were boring or pompous. I also had Sam Shepard encouraging me. Sam and I had written some songs together by that time, and he encouraged me to do a little singing or put some music with my poetry. And I’d met Lenny Kaye [Patti’s bandmate of twenty-five years]—so things just evolved in a certain way. When I was younger, I felt it was my duty to wake people up. I thought poetry was asleep. I thought rock ‘n’ roll was sleep. I didn’t see myself as gifted enough to do the work, but I did think I could stir things up enough to wake people and maybe inspire those who had the greatness and should be working. I remember the night vividly. It was February 10, 1971—Bertolt Brecht’s birthday. There was a full moon. Because I was reading a lot of [Jean] Genet at the time, I dedicated my performance to crime. I had a lot of energy then, a lot of irreverent bravado. All the Warhol people were there to see Gerard, who was going to go on after me, and of course Robert was there with his entourage looking like a proud parent. It was really exciting. One of the great nights of my life. If you heard a tape of it, it might not seem so exciting, but the actual air of the night was really electric and joyous.

IS: What did you do afterward?

PS: That night?

IS: Yes, when it was over.

PS: Probably listened to Hank Williams and drank tequila with Sam.

IS: And what came next?

PS: I didn’t really expect it to go anywhere. I didn’t think I was all of a sudden going to start doing poetry readings, or make a record and have a rock ‘n’ roll band. Sam and I wrote this little play together called Cowboy Mouth, in which my character is talking about the hope that someone would come and make sure that rock ‘n’ roll wouldn’t die.

Is: By early 1971 the seeds for that possibility were already there.

PS: Yes. Jimi Hendrix had died, and not long after, we lost Jim Morrison. I was concerned that there wasn’t any active and strong guardian of the form. But it never occurred to me that I would be entering that arena.

IS: You sure did, though.

PS: It was an organic process. I continued to do occasional readings. Usually on Rimbaud’s birthday or Jim Morrison’s, or De Kooning’s birthdays. I’d do them in a little gallery or on a rooftop. And then Lenny and I started working some more. We developed more songs. And because there wasn’t really any place for us to play, I did a lot of bars by myself—opening acts where I spent the whole time sparring with people and trying to convince them that I had the right to be there. I became so good at sparring that that became my night’s work, just sparring. I was a real serious student of Johnny Carson, so I was ready for them. I was really good at one-liners and at being able to protect myself from the barbs of others with an even better barb. And then the next pivotal thing that happened was that Lenny and I were introduced to Richard Sohl. We immediately became a three-piece. We were able to develop our ideas. Richard was an extremely gifted musician and gifted at improvisation. We just gaily went our way, not with any particular design at the time except to do good work.

IS: The early ’70s were such a high point in experimentation.

PS: Yes, there was an energy that happened in 1974. Looking back, I think a lot of it had to do with poets moving into the area of rock ‘n’ roll. There was a lot of physical and cerebral energy that was like a little meteor spinning around. It wound up in areas like the club CBGBs. If it was a Superman comic, it would be like kryptonite—Fred [“Sonic” Smith, Patti’s late husband] used to call that kind of energy “stratium.” It was just a word he made up. Anyway, I felt like we were on the right track. Dylan came to see us at the Bitter End, and I felt like he gave us a little nod that we were doing well. Its always been important to me to do well. Not to be successful—not that there’s anything wrong with being successful, but that wasn’t our prime motivation. So that’s how we wound up with a damn rock ‘n’ roll band. We were happy. We had really great camaraderie. We had a mission.

IS: And then in 1979 you all dispersed—you to Detroit and Fred, and the music you did together, and the kids you had together, and of course the continued work that you did on your own. It was clearly an important time.

PS: Fred and I raised our children ourselves, and we went through the same kinds of things other people did, including financial difficulties. We lived simply and frugally. Our house flooded and we sandbagged to save it. We had to go through our own Little House on the Prairie existence, which certainly wasn’t as hard as other people’s, but I did learn. An artist may have burdens the ordinary citizen doesn’t know, but the ordinary citizen has burdens that many artists never even touch.

IS: Go on.

PS: In the period where I had to live the life of a citizen—a life where, like everybody else, I did tons of laundry and cleaned toilet bowls, changed hundreds of diapers and nursed children—I learned a lot. It’s hard to get up in the morning and spend most of your day in the service of others.

IS: And those who do rarely get a chance to express what it’s like.

PS: I feel very blessed, because I’ve been privileged enough in this life to experience both. Genet wrote essays about sitting on a train looking at this old man who seems disgusting to hun. Suddenly, Genet realizes that the old man is also him and it is a humbling experience.

IS: You’d become a big star. Did you feel that you needed humbling?

PS: I didn’t do it for that reason, but Fred knew it was necessary. I learned almost all of those things from him, and I’m extremely grateful to him. It wasn’t an easy task to teach me, either.

IS: In addition to your love for Fred, did you choose another direction for your work because you were ambivalent about fame, whatever fame means?

PS: I can tell you what it means. It doesn’t mean a fucking thing. But I don’t know. Perhaps I had a certain amount of contempt for what fame can do, though I did whatever I wanted. I’ve never bent to the company, and I have no shame about the way my work was presented back then. If I have any regrets, I could say that I’m sorry I wasn’t a better writer or a better singer. Still, I did as well as I could and that’s all I can do.

IS: Now you’re dealing with the process of mythologizing, which happens when someone goes away. Even that phrase “goes away” strikes me as wrong for you—you never went away. You went to do your work, d to your life. Artists have done that since the beginning of time—they’ve come in and out and back in when they had something to say or show. So what do you think about the mythologizing?

PS: I try to stay away from it. People always want to send me reviews and articles, but I stay away from all that as much as I can. I can’t control what happens, though. I can’t control the fact that someone is writing it unauthorized biography of me. I’m really trying not to have my head turned, not to be corrupted, tainted, or depressed. I’m trying to stay as clean as possible.

IS: Clean. I love that word in the way you’re using It. Not as some puritanical concept, but as a stripping down to what matters.

PS: Me too. I love that word. Onstage I’ll try to be as “clean” as possible, but that doesn’t mean if someone gives me a load of shit I won’t let ’em have it.

IS: That brings us to now.

PS: Now I’m working with some of the same people that I worked with in the ’70s. Not all of the same people—there are new ones, too, and I feel that we’ll do well. There are six of us at the moment. There is Lenny [Kaye], Tony Shanahan, and Jay Dee Daugherty—the only drummer I’ve ever had—so the things between us that are both spoken and unspoken are very evolved. Tom Verlaine and I have worked together back and forth since 1974. There’s also new energy from Oliver Ray, who’s twenty-three and in touch with a whole other area of knowledge. Oliver and I wrote the pivotal piece on the new record together. It’s a ten-minute-long track called “Fireflies,” and even though Oliver and I wrote it, the most important interpreter of it is Tom. Tom is one of the greatest guitar players we have. Every time I walk out onstage these days, I feel like a lotus in a junkyard. It’s like this huge flower just opens slowly through the night. I don’t know how long we’ll all work together, but I think we have a good thing. It’s like planets converging, sort of showing what they can do; some of it being awkward, some of it being beautiful, some of it being humorous, some of it being transporting—and almost always flawed. So I’m pretty happy. I just have to take a deep breath and salute the ones that are gone. Richard [Sohl] is gone. Robert [Mapplethorpe] is gone. My brother, Todd—who always was the head of my crew and I loved working with him–is gone. Fred’s gone. And I have to keep on working. I have to do my work and think of them and allow myself to be enhanced by the things each of them gave me. I have Fred and the life we had together. I have that in me and I continuously try to dip my fingers in it or wash my face with it. And right from the beginning Robert and I had an unconditional, mutual belief in each other’s choices. Even if either one of us made choices that were painful for the other, our care for each other was unconditional. His complete belief in me was such a gift to receive early in life. And that belief was Robert’s legacy to me. It’s allowed me to keep my pride in humiliating times. Humiliating sometimes being nothing more than when I just couldn’t work and felt desperate. I’ve always thrived on the encouragement of others. I’m grateful because I had that kind of support my whole life. I had it from family members from my sister, Linda, and my brother, Todd. I was blessed with that. Sometimes people come up to me and say, “Oh, I feel so bad. So many bad things have happened to you.” And I say, “No, they haven’t happened to me. I’ve been, you know, thrice, four times blessed.” Even in my most desperate moments, I find myself magnified by the spirit of my loved ones. So I can’t say that only bad things have happened to me. I can say that I feel these blows that really take our breath away. But, I’ve seen how we can marshal ourselves and get up again and look around. And if we’re patient, everyone, no matter what they’ve been through, can feel joy again. I think joy never leaves you. It might seem like it does sometimes, but it will renter you in the most unexpected scenarios. One way to explain it is to say, “It’s as simple as a smile.” You know what mean? No matter how Hallmark that might sound, it doesn’t matter. It might have some awkwardness about it, but . . . Actually, I can’t even say it, because the more I say it the more it’s going away. It’s the light that’s beyond light.

IS: It’s telling that you don’t call the live shows that you’ve been doing a “tour.”

PS: Well, I’m not doing things in the classic music-business way. I did things in that manner in the past but I can’t now, I can only work at certain times, around my kids” school schedule and in a way that doesn’t disrupt our family life. But when I do do things, I like to think I’m journeying to a certain place to say hello, and exchange some thoughts and laughs. [sneezes]

IS: Bless you.

PS: Thank you. I’m not feeling great. I think I have the flu. Today, I realized my body was at work making antibodies for itself, because myth tastes like penicillin. So, some things do take care of themselves. [laughs] I don’t know how that relates to what we’re talking about, but anyway

IS: It’s funny, I was just thinking of your music as an antibody, as a form of healing.

PS: Thank you. Well, art is a great antibody, isn’t it?

IS: Yes, and when it has that kind of energy we were talking about, it performs its “medicine” as it were, all over the “body.” I’m trying to move to the idea of the collective body. It strikes me that your work can move through the culture in lots of different ways. You’ve always been about crossing over, but at the same time you’ve also been labeled—poet, punk, hermit, mother. . . . You’ve been assaulted with various tags. You must be sick of It.

PS: Artists are traditionally resistant to labels. Picasso hated being called a Cubist, and Jackson Pollack hated being called an Abstract Expressionist. I find all these labels so ludicrous and antiquated. People want to call me a “female vocalist,” a punk goddess,” and I’ve often said, “Why do you have to genderize something? You wouldn’t call Picasso a ‘white heterosexual painter,’ would you? He’s an artist.” I started out as a “street poet” and then they had to keep adding labels: “poet/playwright/singer, and so on. Robert used to worry that I had too many titles. He used to say, “You don’t want to be a jack-of-all-trades.” And I said, “I haven’t placed these titles on myself.” I’ve always considered myself a “worker.” I always thought that if there was a band of people who were proud to be called “punk” or felt like they initiated it, then they should be allowed to have their slot. I don’t feel like I’m particularly deserving of the punk-rock laurel, since that was a movement that came after what my group did. But a song like “Rock and Roll Nigger” addressed people who were outside society, and if I ever addressed anyone in particular, I was addressing people who were so miscast and misplaced that no one ever even gave them a label. I’m not addressing any one sort of person, though, at this point in my life. I send my work out to whoever wants it, whether that’s a mother with four kids, or a person who might be perceived as “square,” or a businessperson, or a leper, or kids who want to go to a rock concert. My duties extend to the people I regard as sort of an abstract community. If I tend to that community and to the community of my soul, as well as the community of my children and my fellow workers, then perhaps the work that we do will have a positive avalanche effect. In the ’70s, I had a very romantic idea about being out in the world and having a network of people working with me. I thought of it more as a military regiment. I liked to read books about General Patton, Alexander the Great, and T.E. Lawrence, and I had this view of the people I worked with as troops. The flaw was that I got to the point where I wondered, What war are we fighting? I perceived myself as politically inarticulate and I brooded about that quite a bit. Was it merely fame and fortune I was after? Or was I trying to do something positive? This was most burdensome. And as I step out now, I wonder, What am I after this time?

IS: What do you think you are after?

PS: I’ve been working privately for a long time, but as soon as my foot touched the stage, the people who were sitting in the audience taught me something about why I was there. They called out that they were glad I was back. They gave me confidence. They helped me. That was just the first step. for me to be happy that people are glad to see me. In the wake of this positive response, now I have to think about what my real duties are. And that’s what I’m considering now. Now possessing the confidence they gave me, I have to consider what I can give. Let’s just say that I think any person who aspires, presumes, or feels the calling to be an artist has a built-in sense of duty. They have a duty to God, to themselves, to their gifts, to people. I really believe that there is a chain of being and that this chain has gone all through history. The past communicates with the future and vice versa. We have the chain of heredity, but we also have the chain of the work that comes from the mind and the heart and imagination of man. I feel that’s one of the beautiful parts of human existence.

IS: And one of the parts of how a certain kind of art happens. Sometimes the holes that people are feeling are so big that art is really needed.

PS: Thus the Renaissance. I always find it quite beautiful that the Renaissance was born out of the mouths of rats and plague.

IS: Patti, during our conversation, in the back of my mind has been the word memory. Not just for the obvious reasons, like the fact that your music and your writing in various ways has to do with memory of Fred, say, or of Kurt Cobain.

PS: That’s remembering. But I know why you’re talking about memory. There’s the flux of memory. I find one of the most exciting, beautiful reasons to keep living in terms of one’s work is that great collective pool, or flux, which I believe exists. I believe that everything we need to know is somewhere in that flux. I mean cures for sicknesses, the face of God… sometimes I have felt like every fiber of myself has shut down. And I remember once lying down, listening to Puccini, and leafing through a book. I looked at a small self-portrait of Raphael, and somehow I remembered being in the middle of Detroit and looking at an old stone sculpture. I recalled putting my hand on the stone and imagining the person who had carved this thing, and all of a sudden I felt the blood in my body and I just felt awake. Sometimes it happens when you go to a place. There was something about the atmosphere of Naples. I entered that city alone and I immediately started to cry. I don’t know why. I remember being in the car and looking at the streets. There were no people on the streets and everything was white and narrow, and I just wept. I had a complete sense of return, even though I’d never been to Naples before. I don’t know if I’d seen too many Antonioni movies, or whatever, but there was something about that city that just took my heart. Is that where Robert took the picture of the ship that I have in The Coral Sea? As soon as I saw that photograph. I fell for it immediately. I was just so taken with it.

IS: Yes. He was up early in the morning because he wanted to see if there was any place open to buy cigarettes. There wasn’t.

PS: He didn’t get the cigarettes. He got something more enduring than a cigarette. When Bert died, they called me early that morning and I was up watching Tosca. I immediately started writing, because I just couldn’t cry any more. I had cried so much throughout his illness. I now see that time as the youth of my grief. I just thought the best thing I could do for him was work. So I started writing. This photograph was right at the forefront of my mind, my thought, my breath. I just sat there like a kid scribbling. I wrote every day until it was done, and then I put it away in an envelope until I decided to bring it out. Now, seven years later, the little book I wrote for him is coming out as The Coral Sea [recently published by W.W. Norton].

IS: It seems like it’s the perfect moment for all this stuff to be coming out. Robert always used to talk about the “perfect moment.” He meant it in terms of the perfect moment to capture the picture. To me, what you’re doing captures our time. It’s got the darkness, it’s got the light, It’s got the humanness that is so urgent. It’s the fragility and it’s got the strength—it reflects us. Are you feeling this mirror when you look at the people who have come to see you now?

PS: I did this benefit in Jack Kerouac’s hometown. Lowell, Massachusetts, and this boy came up to me. He was about sixteen, wearing a motorcycle jacket a nice looking kid. He said to me, “Gee you weren’t really what I thought you’d be like.” I said, What did you think I’d be like?” And he said, “You know—punk.” And I said, “What did you find?” And he said, “You’re, like, a person.” So I asked him, “Was it all right?” And he said, “Yeah, it was.” Something I’ve noticed in this recent short stint of performing I’ve done is that when I look at the people in front of me, they’re different than they were in the “70s. Then, a lot of the audience was dressed like on our Horses record cover. I look out at people now, and I see guys who could be truck drivers or fans at a Grateful Dead concert. I see young kids and people with children. I can tell there are different sexual preferences out there. I can tell that some of these people are sub. urban, some seem lost. and some seem hip. What makes me happy is that they’re there.