Artists at Work: Pat Steir

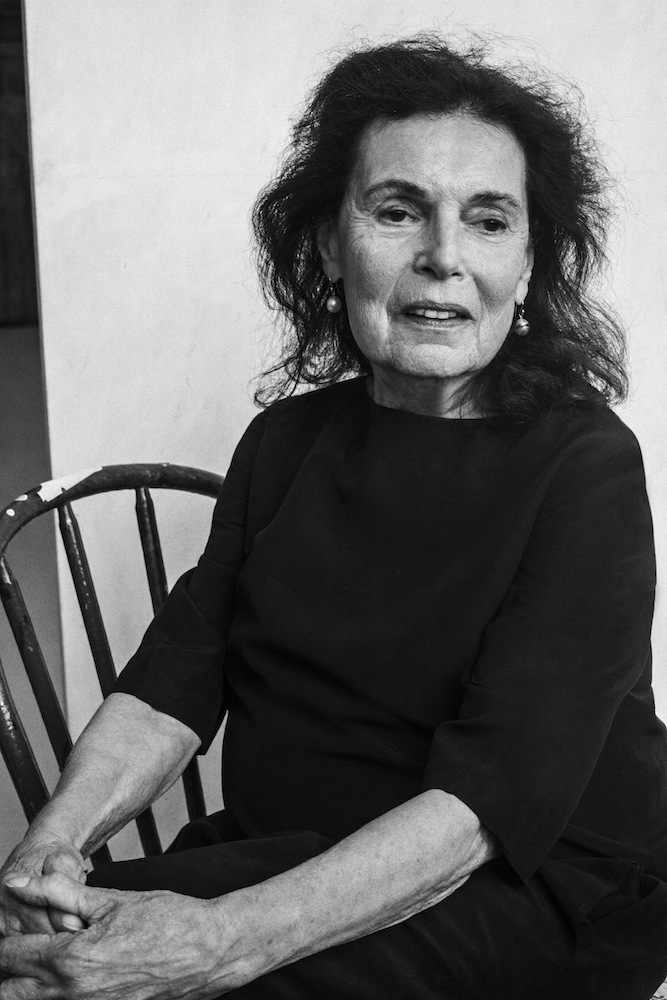

PAT STEIR IN NEW YORK, JULY 2016. PHOTOS: VICTORIA STEVENS.

This summer, during group shows and ahead of fall exhibition openings, we’re visiting New York-based artists in their studios.

Pat Steir is a full-time painter, but in another life, she was likely an acclaimed poet. She speaks with entrancing lyricism and deft art historical knowledge. Her canvases are like choreographies, akin perhaps to Warhol’s “Dance Diagrams,” albeit much more beautiful. Each mark is a record of her movement and presense, forming acrobatic waterfalls of pigment, and yet they seem to emerge immaculately from nature without the aid of a human hand. She is both highly conceptual and deeply emotional, combining the tenets of the New York School with later developments in abstract painting. She has never waivered from her kinship with paint as an expressive medium, and is one of few artists who could be credited with such a forceful presence in post-war art.

When we visited Steir in her Chelsea studio, the walls were adorned with enormous canvases awash with kaleidescopic color—a perfect backdrop for the conversation that ensued. This November, we will be treated to a show of her new and historic works at Dominique Lévy Gallery in London.

WILLIAM J. SIMMONS: In your interview in BOMB and in several other places, the comparison to Pollock is made, and I was thinking about how there is really great imagery of you in the process of painting. But when they did that film of Pollock, he went on a bender and killed himself. So where does privacy and publicness exist in your work?

STEIR: Two things—Pollock was an inventor. I don’t know if he killed himself by accident or by plan, but he did invent something. He is considered an abstract painter. I consider my work non-objective and I think abstract is an abstraction of something, like a landscape. Abstraction means something is abstracted. It relates to something. Non-objective relates to nothing. It has no object.

SIMMONS: That’s a really interesting distinction.

STEIR: One thing Pollock said that was very good was, “I am nature.” That was not actually a macho statement, because everyone is nature too. What else could we possibly be? Leonardo da Vinci was nature. Da Vinci understood the movement of water. He was living in Rome, and he was far from water—a long wagon ride away or however he got around. He understood from his own blood flow the flow of water. He understood, from the music in his veins, the flow of water. And that’s objective abstraction.

But my work is non-objective, so what I’m really trying to do is different than Pollock or the abstract expressionists, who were expressing; they were expressionists. I don’t know if the audience called them abstract expressionists or if that’s what they called themselves, because they were also spiritual painters. Mondrian was basically a spiritual painter, not an abstract painter. He found pure motion which is horizontal and vertical.

SIMMONS: I saw Hilma af Klint’s paintings at the New Museum a couple of days ago, and I was thinking about how we often sideline or forget the legacy of spiritualism when we talk about male painters. With Wassily Kandinsky, however, it was an entirely spiritual operation. But with af Klint, it’s something that really drives the narrative. So I’d be interested to hear how you navigate that.

STEIR: Well, it drives the narrative in Agnes Martin too and in John Cage and in Philip Guston. The spiritual in my art is giving up control. My paintings are based on what I can do, and what I can do is not controlled. So I give up control, and that’s the spiritual aspect of the work—taking what comes and relinquishing control. Although they look very controlled, they’re really not, because it’s all poured paint.

The control is in the weight of the paint, the temperature of the air, the movement of the air. This red one was painted there in that spot [points toward paintings in progress]. With the green one, which is an underpainting, the air movement is different, so the surface is different. The spiritual aspect is hidden, but I really believe in that. I have a friend who says a beautiful painting can cure headaches, but I want it to cure a little bit more! I want it to cure the society of voting for Donald Trump. I bring the campaign up with every cab driver in New York, not to vote for Donald Trump.

SIMMONS: So could your paintings maybe be described as alters or as totems, or as some sort of relics?

STEIR: No, no. They will be relics if they’re lucky! Every piece of art will be if it’s lucky enough to be dug up, if there’s anything to dig up. But I just think it’s funny, because somebody will ask me what’s my purpose in making art. What’s my purpose? I’m purposeless. I’m making art because I want you to look at that painting and I want it to affect you in some way, to change what you see, to change how you see it. To change how you see something, whatever. I want art to affect the viewer and for the viewer to take it away to enhance, embrace, and elevate life. That’s the spiritual aspect. Painting is a spiritual practice, but sometimes it is hard to give up control!

SIMMONS: Well, it’s really interesting because I interviewed Julie Mehretu a few months ago. We were talking about the political implications of continuing to work in abstraction, and she said a very similar thing as you just did, in that it’s not necessarily about representing politics, but rather affecting the politics of vision.

STEIR: Yes, but her work is more overtly political than mine. Though it’s abstract, you have to expand yourself to see it. Everything you do on Earth is political. Art as a political gesture is committed to making something beautiful, and then understanding what beauty is in your own time, because what we think of as beauty changes with time. The notion of beauty everywhere changes. I want to make an object, not a pile of dirt on the floor, not a video. I want to make something less transient. Not that the paintings will last forever, but they’ll last longer than a videotape; they just will. I made things on floppy disks, and I can’t play them. I have stacks of floppy disks, and there’s no equipment to play it on. So I’m committed to making an object. Painting is an object, but it’s also a voice. I don’t see them as objects; I see them as voices.

SIMMONS: Well that reminds me of your interview in BOMB where you said—and I found this so evocative—I’m going to butcher it, but I’ll try; that beauty is equally terrifying in a way, because people cry more at weddings than they cry at funerals. And so it’s really interesting to think about your connection of the the dire political situations that we’re in with this urge for beauty in all of its iterations.

STEIR: Art is a way you discover the past, and so it brings the past into the present and the future. That’s why we have anthropologists who dig up the art from the past. You can see the refinement in the society by the art. And people will see our lack of refinement when they dig up our art. But art is the most important way of recording history.

We live in a time when people are afraid of beauty, because beauty passes; you can’t hang on to it. And even if you see something or someone beautiful, the next time you hear it, it sounds different. So you can’t cling to beauty; beauty passes and when that passes, you realize you pass too, and you will die. And that’s why people cry at a beautiful view, a beautiful lecture, a beautiful painting, a new baby. New babies make everybody cry. At weddings people cry because you see this happy couple and you think, “Oh my god, I wonder what’s going to happen to them.” You know that moment can’t possibly last, because external things intervene. So beauty is terrifying. Rainer Maria Rilke said, “Every angel is terrifying; beauty is nothing but the beginning of terror.” I have a whole theory even. When you see the holy halo around the holy heads on holy paintings—the halo is a bright light so you can’t see the face. The face comes in darkness because it would be too beautiful to see. If there were such a thing as a holy person, a god, with a halo around his head, you wouldn’t be able to see his face because the beauty would be terrifying.

SIMMONS: That makes sense then that Satan was a former angel, right?

STEIR: Well I don’t know! I don’t think that far. I think this about painting. I’m thinking about the way that paintings are formed—the light in reality would mask the face, and it wouldn’t be visible. The face itself would be too beautiful to see.

SIMMONS: When one is depressed, the instinct is, for the exact reason that you mentioned, to avoid moments of beauty because you can’t handle being reminded of the transience of life.

STEIR: You know, my sister died very young and she was in a nursing home. She could see the tops of the trees along the street from her bed. And I kept saying you can see these trees, they’re so beautiful, you can see the sunlight, it’s so beautiful. You’re completely right, it was too much for her to look at. I’m the opposite. I have my moods, but I can always see something beautiful.

FOR MORE ON PAT STEIR, VISIT DOMINIQUE LÉVY’S WEBSITE.