Remembering Leonard Cohen

On Monday, the great Leonard Cohen died at age 82. Just shy of 50 years ago, he released his first album, Songs of Leonard Cohen, and in a statement to Rolling Stone, his son Adam said his father was at work, pen to page, through his final days. A poet, songwriter, singer, deep thinker, and voice for so many, we will remember Cohen for—and through—his potent, ruminative lyricism and haunting bass voice. He released his final album, You Want it Darker (Columbia Records), only three weeks ago.

For the November 1995 issue of Interview, Cohen visited his friend Anjelica Huston and let us listen in. He spoke of his monastic life; passion and Prozac; love, and how to assure it isn’t lost. —Haley Weiss

Leonard Cohen

By Anjelica Huston

Here the great, smart, original songwriter and musician talks to the great, smart, original actress Anjelica Huston. This conversation was occasioned by the new record, Tower of Song, which features interpretations of some of Cohen’s killer records by a treasure trove of musicians, including Tori Amos and Elton John. But the last thing that a guy like Cohen would do is plug a project that honors his thirty years of creating immortal popular music. He is a man who wants to go into the deep stuff, which is why his songs have been so meaningful to so many people—including the late Kurt Cobain, who once wrote, “Give me a Leonard Cohen afterworld, so I can sigh eternally.”

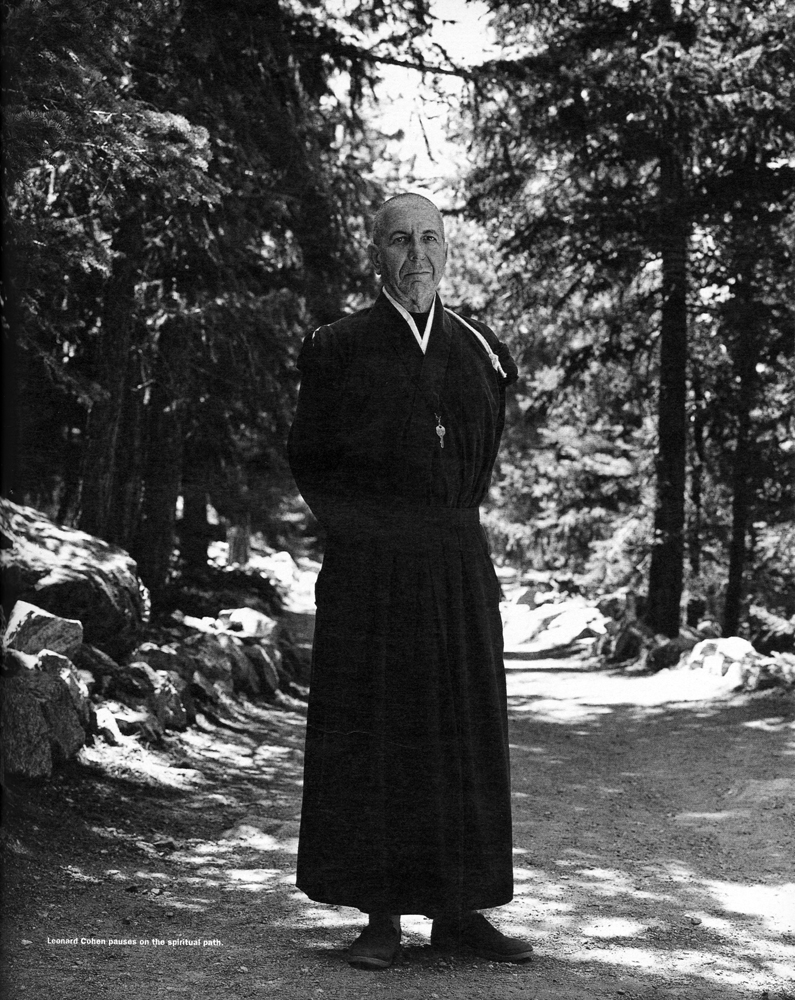

I met Leonard Cohen through a mutual friend in Montreal when I was making a movie there in 1988. He took me to a pool hall, to a church, and then we ate pastrami sandwiches. Part wolf, part angel, his music speaks to the soul, his love songs from the dark recesses of the heart. He comes to my house in Venice, California wearing his usual uniform—white shirt, dark suit. His hair is cropped short. He has come form an ashram on Mount Baldy, in California, where he has been living for some time.

ANJELICA HUSTON: You said on the phone that you’ve been living in a Zen monastery. Do you chant there?

LEONARD COHEN: It is very, very physical. In the old practice there was no word for experience. The phrase was “attaining in the body. The [point was that] no idea is going to come and transform you. [The transformation] was going to be experienced … cellularly. This particular school of Zen has always considered itself the Marines of the spiritual world, so it has a kind of bias against conceptual thinking in favor of a very rigorous physical life.

HUSTON: Does that stop you from thinking a good deal of the time?

COHEN: Nothing can stop you from thinking. The human mind is designed to think continually. Something I wrote quite a few years ago was, “The voices in my head, they don’t care what I do, they just want to argue the matter through and through.” It is a common mistake, to think you’re going to go into some kind of spiritual practice and you’re going to be relieved of the human burdens, from human crosses like thought, jealousy, despair—in fact, if anything, these feelings are amplified.

HUSTON: What is it like for you to have other people sing your songs?

COHEN: Other people singing my songs is something that I’ve never been casual about. I’ve always been very touched by it and I always go into immediate critical suspension. You know, no one’s ever done one of my songs badly. People say to me, “God, so-and-so wrecked that song.” Well, I’m unaware of it. Anybody doing one of my tunes has earned my gratitude, and I don’t get that many covers where I have the luxury to choose. But as soon as anybody does one of my songs, I rejoice. This particular case of all these great singers doing my work—the implications are very rich and the temptation to think of the outcome of these masses of the mainstream injecting my work into the marketplace, you know, it’s a very sweet speculation.

HUSTON: By spending time monastically, do you think that you’ve attained a more comfortable situation in passion … love?

COHEN: There are a few things that deal with passion. There’s Prozac.

HUSTON: [laughs] Have you taken Prozac?

COHEN: Yes, I looked into it. I must say that it is certainly a wonder drug. What it does is completely annihilate the sexual drive, so the question of passion hardly arises. What’s life, you know? It has all these pesky details that accompany it. I noticed that when I was on Prozac my relationship with the landscape improved. I actually stopped thinking about myself for a minute or two, because most of the thoughts one has about oneself are involved with desire or loneliness or isolation or strategies to overcome them.

HUSTON: Or food.

COHEN: Or food.

HUSTON: Why did you stop taking it?

COHEN: It didn’t seem to have any effect whatsoever on my melancholy, my dark vision, and everything else that I’d taken it for.

HUSTON: Aha. So do you smoke and drink with the monks? This sounds like a heavenly ashram.

COHEN: Well, you can do anything you want to if you can find the time. It’s a very rigorous day. It starts at 2:30 in the morning and often doesn’t end until midnight, so if you can actually find a moment to have a drink or a smoke, you’re quite welcome to, as long as it doesn’t interfere with your capacity to follow the schedule. A certain kind of reckless machismo develops up there, where even though you know that every sip you take is cutting into the sleep you need, sometimes at the end of the day you feel like sitting around and having a drink and a smoke. You know, you sit for long periods of time, and during the intensive weeks, which are one out of every month, you sit for about eighteen hours a day. You begin to examine the panic of your mind. So it seems to be that if you can stay still for any amount of time, anything more than a minute or two, which we rarely ever do, some things are disclosed to you. Of course, you shake your legs after meals and go to the bathroom, that sort of thing, but basically there’s nothing but stillness for about eighteen hours a day, and everything comes up.

HUSTON: Have you always had a sense of interior panic?

COHEN: Always. I didn’t really know what to call it for a long time, but I have a friend in Greece who used that word panic a lot, and I found myself resisting it, until I totally accepted that as a precise description of my interior condition. It was mostly panic from one moment to the next. And nothing much else was going on. And any of the decisions that I made, if one could actually locate a shape or form, were all within a wall, the landscape of music.

HUSTON: Can you ascribe it to anything you can remember?

COHEN: I don’t know what it is. Most of our distractions are designed to invite us away from this recognition, which is a good idea.

HUSTON: Do you think that’s what the present trend in extremely violent films and music is about?

COHEN: I think culture’s always been violent, and it is something we find very entertaining. Not only does it reflect our social reality, but it also reflects our psychic reality. We actually lead very violent, passionate lives and I think that we’re hungry for insights into this condition. That’s why we get all that stuff on television. It’s really where we are, really what we are. Probably all cultures, certainly Western culture, always have been violent. At the very center of our culture is a crucified man, a tortured man hanging on a cross of wood. You have an image of violence at the very center of our spiritual investigation. Suffering, violent suffering, seems to be something that corresponds with something that we experience. But maybe the culture is [particularly] shabby now. Maybe it’s because I’m over sixty, that I can feel that about everything.

HUSTON: I’m inclined to agree with you, and I’m not sixty yet.

COHEN: [laughs]

HUSTON: Isn’t this what’s currently referred to as a decadent period?

COHEN: I don’t know if it is or not. Certainly within any decadent period, you would probably find the purest expressions of conviction, and I do not see that in many of the people I know. Today [people] are ready to take emergency cures, whatever they are, if it’s violence, if it’s a fascination with serial killing or whatever—the discomfort is so intense. Maybe it’s always been like that, certainly it is now. Public speech seems terribly shabby, with the exception of a few black orators. The public rhetoric is hopelessly boring. It’s incredible they actually get anybody to go to the polls. The level of debate is terribly shabby; if there is a debate at all, I can’t quite locate it.

HUSTON: How do you think that’s going to affect the future, given the fact that we are panicked and that things seem to be closing in on us?

COHEN: This just may be each individual human’s translation of the certainty of their own death. I mean, things are closing in on us in a real way. I found when I was writing about the future, in a song called “The Future,” I found that the hook I came up with, the one I could get behind and sing in several hundred concerts, was, “I’ve seen the future baby, it is murder.” That seems to be true.

HUSTON: It’s certainly true in Los Angeles, but that’s the present, too.

COHEN: Yes, yes, I don’t know. [pauses] I don’t know if one loses interest in [all that and in the] popular culture after a while. I was very interested in it at certain points in my life, and I think I learned a great deal from the movies and the books and the songs, but for some odd reason, maybe it’s just crotchety old age, I don’t see very much around that speaks to my particular version of panic. So consequently, one can leave off a number of pursuits. I don’t care if I see a movie for weeks or months. I used to love television. I don’t have a television set up [in the mountains], of course, but I find I don’t miss it at all, or the newspaper. I’ve sneaked a radio into by cabin, but I find I turn it on very rarely.

HUSTON: What do you listen to?

COHEN: The songs, you know. There’s always a nice tune—helps you get the dishes done. I like to get the news from time to time—not too often. I don’t feel deprived. [looking at curtains in Huston’s house] Are these from Shabby Chic [a furniture store in New York and Los Angeles]?

HUSTON: No those are recycled curtains from my last house.

COHEN: They’re really good.

HUSTON: Thank you. My husband built me this house.

COHEN: Not since the Taj Mahal has a piece of architecture been so successful at commemorating love.

HUSTON: Do you think love can last?

COHEN: I think love lasts. I think it’s the nature of love to last. I think it’s eternal, but I think we don’t know what to do with it much of the time. Because of its eternal and powerful and mysterious qualities, our panicked responses to it are inappropriate and often tragic. But the thing itself, when it can be appropriately assimilated into the landscape of panic, is the only redeeming possibility for human beings.

HUSTON: Why do you think it is that when we fall in love, our mouths become dry and we shake and our hearts beat too loud and we’re fools?

COHEN: Because we are awakening from the dream of isolation, from the dream of loneliness, and it’s a terrible shock, you know? It’s a delicious, terrible shock that none of us knows what to do with. Part of the shabbiness of our culture, if indeed it is shabby, is that it doesn’t seem to prepare people. With all the songs about love and all the movies and all the books, there doesn’t seem to be any way that we can prepare the human heart for this experience. Maybe we, the cultural workers like you and I, could apply ourselves. We’re not going to resolve it in this moment or even in this generation, but perhaps as some kind of agenda we could invite our writers and cultural workers to address the problem a little more responsibly, because people are suffering tremendously from a want of data. The psychologists are valiantly trying to provide us with answers, the religious people are trying to provide us with answers. I think it properly falls on the cultural workers to investigate this predicament with a little less concern for the marketplace and a little more concern for their higher calling.

HUSTON: What do you suggest?

COHEN: Just to get serious about this thing, you know. One has to be compassionate. It’s true that people are up against things, economically and emotionally. The obstacles are great and the suffering is great and people have got to make a living. It’s easy to look down from the summit you’ve reached, or even the summit I’ve reached, and talk about the responsibilities of the artist, but most people are just trying to get their foot in the door and make a living. So we’ve got to temper anything we say with that. On the other hand, you’ve got to be serious about what you do. And you’ve got to understand the price you pay for frivolity or just for greed—it’s a very high price, especially if you’re involved in this sacred material, which is about the human heart and human desire and human tragedy. If there isn’t some element of seriousness in the training of the artist or in the atmosphere that surrounds the enterprise, then this shabbiness grows and eventually overwhelms it. I think that’s what we’re in now. It’s hard to be serious about so many things. [Look at the whole emphasis] on the charts, if you’re a songwriter. Over the years, I saw that arise, where people were no longer interested in the song.

HUSTON: Yeah, I remember the same thing. Now in every small town in America, they’re talking about numbers. And it seems to me that it’s all about placement and cockfeathers. It’s not about seriousness or soul.

COHEN: But I think there’s an appetite for seriousness. Seriousness is voluptuous, and very few people have allowed themselves the luxury of it. Seriousness is not Calvinistic, it’s not a renunciation, it’s the very opposite of that. Seriousness is the deepest pleasure we have. But now I see people allowing their lives to diminish, to become shallow, so they can’t enjoy the deep wells of experience. Maybe it’s always been this way, when the heart tends to shut down. If only the heart shut down and there were no repercussions, it would be O.K., but when the heart shuts down, the whole system goes into a kind of despair that is intolerable.

HUSTON: Decay.

COHEN: Yeah, and you really feel lousy. If it just shut down and you really did become a zombie—to be shut down with a wound is no good. That’s where I’ve seen many of my friends and myself. And that’s why I’ve taken this radical solution [to live in the ashram]. It’s certainly not for everybody. I would never suggest that everybody should follow this kind of regime.

HUSTON: [laughs]

COHEN: But to keep our hearts open is probably the most urgent responsibility you have as you get older. Because when you’re younger, you do have that thing that you were talking about where the mouth goes dry. I mean you have reactions, and you do fall in love.

HUSTON: Is that love a crush? What is that feeling?

COHEN: I don’t think there’s any difference between a crush and profound love. I think the experience is that you dissolve your sentries and your battalions for a moment and you really do see that there is this unfixed free-flowing energy of emotion and thought between people, that it really is there. It’s tangible and you can almost ride on it into another person’s breast. Your heart opens and of course you’re completely panicked because you’re used to guarding this organ with your life.

HUSTON: With your chest.

COHEN: With your chest, right. So when it opens, call it … it’s love. I think that all the spiritual training is just to be able to allow you to experience this from a slightly different perspective—one that’s a little more stabilized.

HUSTON: Do you think that that level of happiness is between people or can it come only from one side?

COHEN: I think that is the ocean in which we’re all swimming. We all want to dissolve. We all need that experience of forgetting who you are. Forgetting who you are is such a delicious experience and so frightening that we’re in this conflicted predicament. You want it but you really can’t support it. So I think that really what our training, what our culture, our religious institutions, our educational and cultural institutions should be about is preparing the heart for that journey outside of the cage of the ribs. You know, I think we’re doing pretty well. I mean, it’s not the worst culture that I’ve heard about. We’re not, you know, dumping people into volcanoes.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN THE NOVEMBER 1995 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.