NOW PLAYING

4Columns’ Melissa Anderson Looks Back on 25 Years of Reviewing Movies

Melissa Anderson is your favorite film critic’s favorite film critic. Her reviews are testy, sharp, and impeccably researched. She has a crush on Kristen Stewart, doesn’t give a fuck about the Oscars, and found that the premise of The Substance “could fit on a grain of rice.” She knows that we are living through a Golden Age of watching bold, dangerous, eros-expanding cinema (in the rep theaters of New York City, at least) and a Dark Age for producing anything new or imaginative.

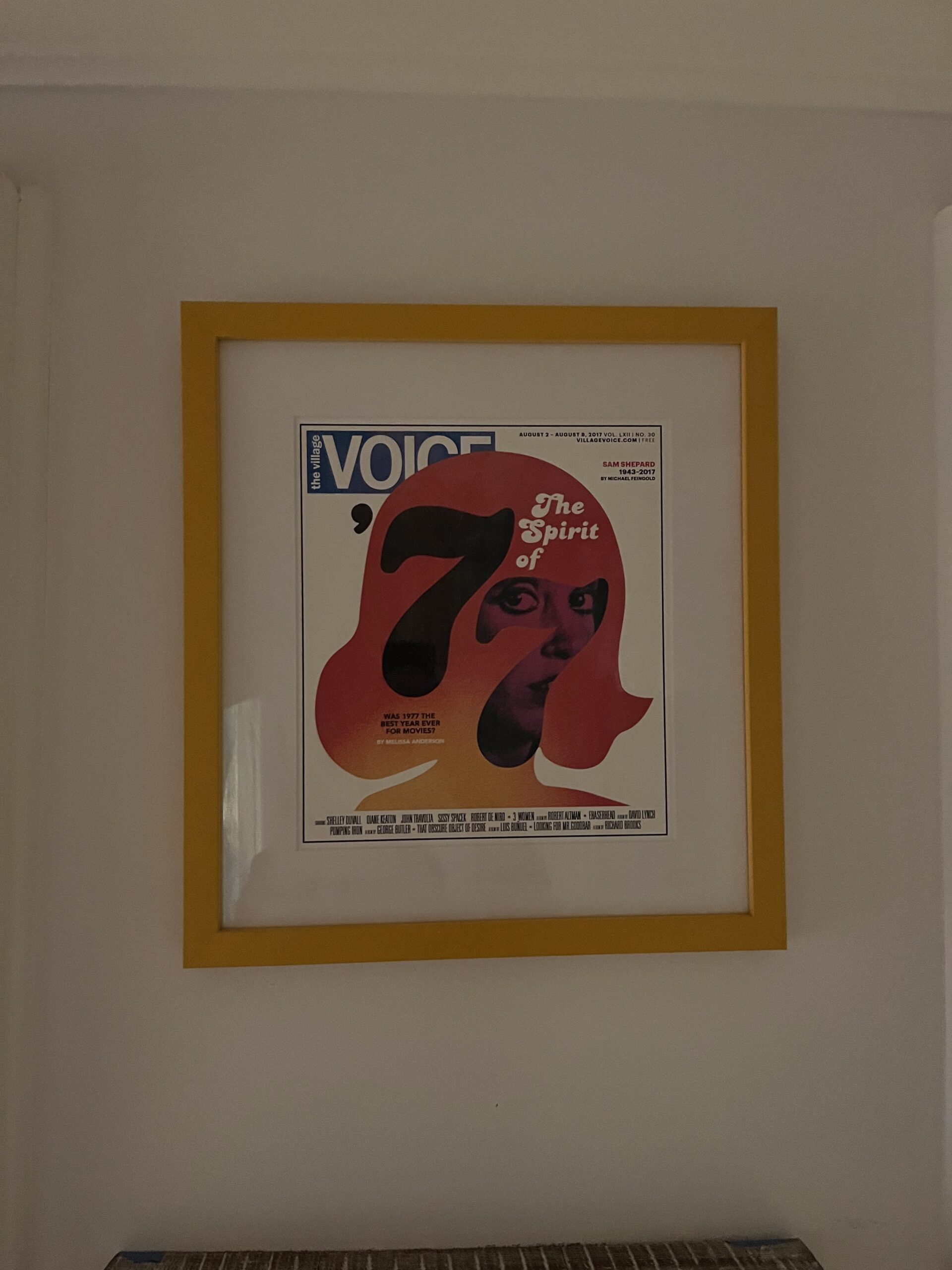

I first encountered her work in 4Columns, where she’s been the editor and lead film critic since 2017, but you may recognize her byline from The Village Voice (back when that was a thing) and Artforum (before they got gobbled up by Penske Media). During a mid-2000s stint at Time Out New York, she learned to write film reviews the length of a haiku. This perhaps explains the brilliant potency of an Anderson take, wherein not only her feelings but her feelings about her feelings shine through between sentences like a neon undercoat. Needless to say, she is a woman of opinions, the most timeless of which (translation: those that did not make her cringe upon reread) have been collected in The Hunger: Film Writing 2012 – 2024, out this month from Film Desk Books. To celebrate its release, Anderson invited me over to her apartment for tea, where we talked about aura, leaving the festival circuit behind, and what she’ll do when 4Columns closes up shop next summer.

———

NOLAN KELLY: Have you seen anything good lately?

MELISSA ANDERSON: I will say this: as we know, the last quarter of any given year is the prestige cinema season.

KELLY: Oscar season, yeah.

ANDERSON: And a lot of those “prestige” movies are usually unwatchable, intolerable. I’m very pleased to report that a lot of the much-touted films have been quite good. Like Kelly Reichardt’s The Mastermind, I really loved. Peter Hujar’s Day, I think, is fantastic. Kleber Mendonça Filho’s The Secret Agent is excellent. But I spend a lot of my film viewing devoted to repertory.

KELLY: [Chantal] Akerman’s Retrospective at MoMA was phenomenal.

ANDERSON: It was. I’m very fortunate to be able to say I have seen almost all of Chantal Akerman’s films. But I did catch up with something I had not seen, which was A Couch in New York, which is her romantic comedy with Juliette Binoche and William Hurt.

KELLY: I saw that one too.

ANDERSON: And with all due respect to the titaness of cinema, I do not know if the romantic comedy was quite the forte of the cinema genius. I also watched an extraordinary documentary made by Sammy Fry, who was Delphine Seyrig’s boyfriend at the time that they were making Jeanne Dielman. Essentially, Delphine is trying to top Chantal, and you can see Chantal really trying to exercise her authority. But at the same time, she’s totally in love with Delphine, and Delphine, I think, might be taking advantage of that. So here are these two tremendous forces, each with differing opinions about how the veal cutlet should be breaded. And this will be a conversation that goes on for 20 minutes: Chantal, with very precise ideas, and Delphine, with certain ideas. Eventually they reach a compromise. But this was an extraordinary document.

KELLY: Yeah, that’s phenomenal. So your book, The Hunger, collects your writing from 2012 to 2024.

ANDERSON: Correct.

KELLY: You say at the end of the book that maybe 2012 was the year that you began to write more openly as an out lesbian spectator.

ANDERSON: I mean, I never hid my status as a daughter of darkness. No. But in the process of deciding what should go into this collection and how far back I should go—with 2000 really being the first year that I began publishing film criticism—it wasn’t until this year of 2012 that I thought, “Okay, I began to establish a certain kind of style, a certain sentence rhythm.” Anything before 2012, I was wincing. I was clutching my stomach thinking, “Who is the idiot who wrote this?”

KELLY: I know that experience. It’s unnerving. So I’m curious, were you freelancing at that time? How did your style come together at that point?

ANDERSON: I’ll just give you a very capsule “herstory” of my writing career. So 2000 is the year that I had my first piece published in The Village Voice, which was a great milestone. And from 2000 to late 2005, I was freelancing primarily for The Village Voice, but not a lot. I was supporting myself as a copy editor— back in the early aughts, you could do that. And then in late 2005, I became the film editor of Time Out New York magazine and was also writing a lot of film reviews. And then from 2009 to late 2015, I was freelancing again for The Village Voice, for Artforum, both online and in print. Those were the years that I was really beginning to hone my style, I guess. And something happened in 2012 where I felt, looking back on the pieces, “Okay, here is where I can see the writer that I am now in 2025. I can carbon-date her emergence to 2012.”

KELLY: Totally. Something I still love about your work is that I can get more of your opinion about a movie in the first sentence than I get from most other people’s reviews.

ANDERSON: I’ve done a couple of interviews now, and one thing that has come up is this trend, more and more, of works of film criticism in which the writer’s opinion about what is being assessed seems to be tamped down significantly.

KELLY: I think that that’s probably true. I certainly think people are less inclined to really trash something, which is a shame, because takedown pieces are some of the best to read, especially yours. But I think certainly in the freelance economy, you really only have the chance to pitch something if you’re personally taken with it.

ANDERSON: Are publications more cowardly because they’re afraid that they’ll be dragged on social media?

KELLY: I don’t know. Maybe it’s the odd bedfellows that magazines and PR now make. It’s hard to get pieces out that don’t have at least some relationship with your sponsor or your advertisers.

ANDERSON: Those Satanic alliances. Surely you’ve gotten these, but the second you walk out of a press screening, you’ll check your email and there will be a very alarmist email from the publicist announcing the review embargo: “You cannot have a thought until December 3rd at noon Eastern Standard Time about this movie.” I am noticing just simply trying to get to see a film has become more impossible.

KELLY: Definitely. And what about film festivals? Do you do the circuit?

ANDERSON: I used to. Well, the first year I went to the Cannes Film Festival was 2005. I went as a freelancer. I went with my dear friend Nathan Lee—someone who I mentioned in the book. Nathan at the time was the chief film critic for The New York Sun. I came along as sort of a second-stringer and also, while I was at Cannes in 2005, wrote a freelance piece for The Voice. So that was my first time there. And when I started at Time Out, I was sent to the Sundance Film Festival in 2006. That was the first, last, and only time I will ever go to the Sundance Film Festival. I found it to be a very unpleasant experience.

KELLY: Really?

ANDERSON: Maybe it was just a very bad year for American independent cinema, but I saw a lot of really bad movies. [Laughs]

KELLY: I’ve never been to Sundance, but I do feel strongly that it’s not what it used to be.

ANDERSON: Where New Queer Cinema really emerged. Let’s just say there was nothing equivalent to Poison or Nowhere or Totally Fucked Up in the Sundance class of 2006. Then I was on the selection committee for the New York Film Festival from 2009 to 2012, and we would all go as a committee to Cannes to scout films. I have been to the Toronto Film Festival a few times, but other than the New York Film Festival, I’ve not been to a film festival since 2012. I will say I do not miss it at all. While it’s truly astonishing to be among the first audiences to see these landmarks of cinema, I found it to be the worst place to actually have thoughts.

You leave the theatre, and then you’re besieged by all these French film crews—”Madame! Madame! Monsieur!”—all these lunatics from French TV channels wanting to know what you think. And then all of these blabbermouth film critics trying to be the first to offer an opinion. All I wanted to do was just get away as fast as possible, go back to the apartment I was renting, and try to write some coherent thoughts.

KELLY: It’s not the best environment to really absorb a movie, especially if you’re trying to see three or four a day.

ANDERSON: Yeah, it’s unhealthy. It’s a disservice to the art form that you’re ostensibly there to support.

KELLY: Absolutely. One of the things I really love about your book is that you position yourself in this lineage of queer writing on cinema that includes Boyd McDonald, Patricia White, and Parker Tyler. And I wonder if that’s related to how you describe yourself as an “acteurist film critic,” somebody who’s far more interested in the stars than the directors.

ANDERSON: Well, I don’t want to say always, but of the pieces that I decided to put in this collection, a thread that connects them is that there’s a focus on the actor. Boyd McDonald certainly was far more interested in talking about performers—or in his case, if you want to be very specific, the performers’ bulges or asses. [Laughs] But yes, a lot of my cinephilia is about being besotted or entranced by the bodies, by the humans I see in front of me, what they do and how they move and how they talk. That, for me, is often the element that is most hypnotizing.

KELLY: This was kind of a revelation for me reading your work. You really get the sense—which I think everybody feels—that stars have this magnetism that’s sort of unable to be completely contained by a single picture. They’re bigger than anything that they’re in. And I love watching you use words like “amour-propre” or “duende.” You have a very specific vocabulary that kind of captures the energy on screen of these people because maybe it’s too ineffable for English.

ANDERSON: It’s hard to put into words, but as a critic, that’s our job, right? What has helped me do that is to try to expand my vocabulary as much as possible. For many years now, I’ve kept this ever-expanding Microsoft Word document where anytime I come across a new word, I enter it and I include its definition. And that has helped me to be as specific in my language as possible. Yes, even if it requires me to borrow words from French or from Spanish.

KELLY: I think the common parlance for this feeling is “aura.” That’s the TikTok term these days. It’s really coming back in style, and it’s something everybody can understand or tap into, I think.

ANDERSON: And it makes them a star. It makes them somebody who you want to keep watching on screen, even if the movie is kind of a turkey. And for this, I’m thinking of the James Gray movie Ad Astra, which I thought was pretty corny. But it has beautiful Brad Pitt—and for me, Brad Pitt’s beauty in that film was augmented by the fact that this is an aging Brad Pitt. There was something so tremendously moving to me about seeing the wrinkles in his face. To see the ravages of time on a star I find very affecting.

KELLY: Do you have an opinion on whether the casting director category should get added for the Oscars?

ANDERSON: I will admit to you, Nolan, I’ve never once thought about this. Other than that piece I wrote in 2016 about how the Oscars made me gay, I really do not spend much time at all thinking about the Oscars and what should be added and what shouldn’t. All of which is to say, yeah, a good casting director is some kind of a genius, and I salute their work.

KELLY: Do you have a favorite programmer or repertory cinema that you’re particularly drawn to at the moment?

ANDERSON: I really can’t single anyone out, because I’ve seen so many extraordinary things within the past year at BAM, at Film Forum, at Anthology, at Film at Lincoln Center, at Light Industry. Each one of these institutions has at least one cinema genius deciding what to bring to us hungry New York City cinephiles.

KELLY: It is a beggar’s banquet. You don’t have to choose.

ANDERSON: Or sometimes, you can feel overwhelmed by choice. But of course, better that than no choice at all.

KELLY: Yeah, absolutely. What feels important to me about Boyd McDonald’s writing is that he’s watching all of this stuff on television. So I’m curious if you feel like—in the age of streaming and repertory cinema, where we have to opt in every time we want to see something—it’s still possible to have that completely unselective attitude towards movies where you just are exposed to stuff that you don’t necessarily seek out on your own.

ANDERSON: I will be coming at this from the position of an eldress. [Laughs] The only streaming service I subscribe to is the Criterion Channel, and doesn’t Criterion have something called “24/7 Criterion,” where you just turn it on and you’re just exposed to whatever they show you?

KELLY: Do they? That sounds great.

ANDERSON: It’s never made clear to me why Boyd McDonald—who seemed to be somebody who would go out to the movies a lot—why most of the pieces in Cruising the Movies are all based on things that he watched on television in his studio apartment on the Upper West Side. I know that he had a drinking problem. I don’t know if there were some other issues that made it difficult for him to want to go out.

KELLY: Right. He was kind of a recluse.

ANDERSON: I guess, ideally, repertory film programming will just make you hungrier for more. A French friend introduced me to this great term 15 years ago. She distinguished “cinephilia”—a love of movies, a love of going to the movies—from “cinephage,” a cinephage being someone who consumes movies indiscriminately and is consumed by them.

KELLY: Oh, I love that.

ANDERSON: The kind of person for whom it seems like it’s a compulsive disorder. They have to go to five movies a day. It seems that movies bring them no pleasure whatsoever, and yet they can’t stop going to them.

KELLY: I guess it’s like being a connoisseur versus a glutton. They can appear very similar, but there’s a certain level of agency and refinement that’s going on on one side.

ANDERSON: Right. If I may ask, are you seeing both new releases—like the glut of new releases this time of year—and also rep stuff? Or are you privileging the newer releases?

KELLY: I do a lot of both. I don’t subscribe to any streaming services other than HBO Max, but I am lucky that I have a pretty large file library that’s been shared around among friends. I watched Klute over the weekend, since that feels like a movie that’s really at the center of a lot of your writing.

ANDERSON: For the first time?

KELLY: Yes. I’m glad I got to see that.

ANDERSON: I’m glad for you. And what did you see last night?

KELLY: I saw this A24 movie called Eternity. It was pretty bad.

ANDERSON: I’ve never even heard of it. Who’s in it?

KELLY: Elizabeth Olsen and Miles Teller. You aren’t missing anything.

ANDERSON: [Laughs] Well, thank you for your service.

KELLY: We’ve covered a lot of ground, but the last thing I really wanted to ask you about is what’s going to happen with 4Columns, or what’s going to happen with you after 4Columns?

ANDERSON: Well, after 10 beautiful years, as you may know, we will be saying farewell the last week of June 2026.

KELLY: It’s so sad. This is something I want to make sure that what readers get out of this, if nothing else, is that they should be reading 4Columns, because it’s always my favorite part of the week when it comes out.

ANDERSON: Well, thank you. That’s very nice to hear. The five of us who work there, we’ve known all along it was never meant to go forever. And 10 years is a nice, beautiful run. What will happen to me afterward? Well, I don’t know. I hope to still be able to write. I mean, I should have a working brain and a working hand, but I’m certainly not very optimistic that there will be any film critic or film editor jobs in the world for me to apply to. I guess this will be a great opportunity for me to just throw my fate open, just be open and ready for anything.

KELLY: Yeah, that’s a good attitude.

ANDERSON: I did an interview last week and this came up and I said, “Well, a real role model in this regard is Fran Lebowitz.” Fran Lebowitz has made her entire career—based her entire career—on talking.

KELLY: Yes.

ANDERSON: I like to talk. I’ve got opinions. So if I could somehow parlay my writing career into a career of talking…

KELLY: She’s very good.

ANDERSON: Yes, she really is, and I certainly envy her bespoke suits.