Barry Jenkins Tells the “Never Rarely Sometimes Always” Stars Why They’re the Modern-Day Thelma and Louise

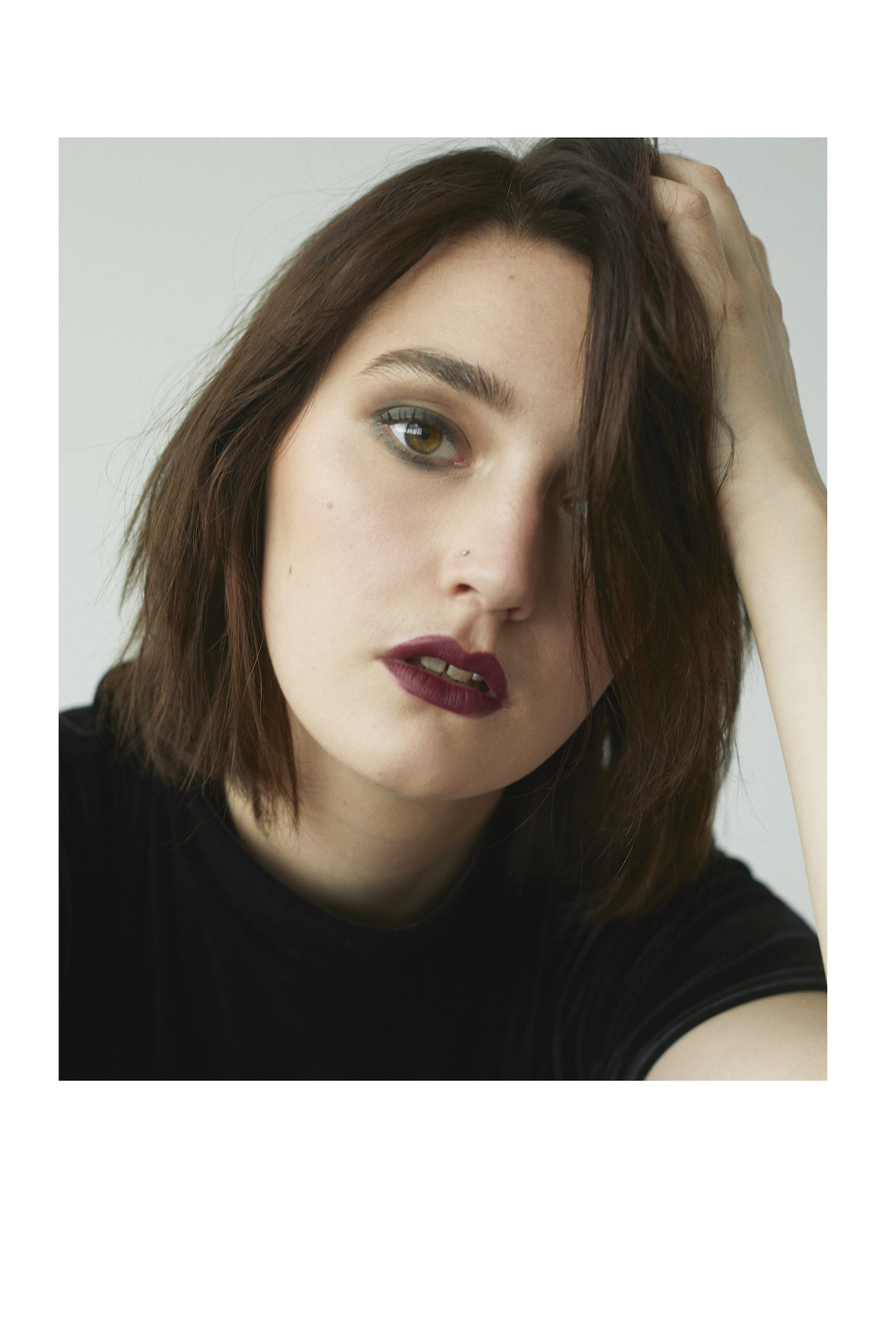

Talia Ryder. Photo by Matthew Priestley.

The most haunting image in Never Rarely Sometimes Always, Eliza Hittman’s stirring Sundance darling, is a smile—the smile of a grey-haired “doctor” who tells a pregnant 17-year-old Autumn (Sidney Flanigan) that while she does not feel ready to be a mother, “once you have that beautiful baby in your arms, you’ll forget you ever had any doubts. I know these things, I’m a mother.” It’s that smile, busting with milky condescension, that brings Autumn to Planned Parenthood. Along with her older cousin Skyler (Talia Ryder), Autumn seeks refuge from her Pennsylvania hometown and its “crisis pregnancy centers” in the anonymous streets of New York City.

Never Rarely Sometimes Always is a restrained look at the quiet resilience of a young woman who is misunderstood in equal measure by her parents, classmates, and the healthcare system. But it’s also a rare depiction of friendship in its highest form: an invisible thread of unyielding support between two very different people. Sadly, despite its festival circuit success, the film was released on March 13th, during the first weekend of national lockdown orders due to the Coronavirus pandemic. And yet, there’s a silver lining: in the thick of an unparalleled crisis for the future of American reproductive justice, this little gem of a film about abortion starring two unknown actors is now available on VOD.

This is a point not lost on the Moonlight director Barry Jenkins, one of the movie’s producers and a filmmaker with a similar talent for painting intimate portraits of people society likes to ignore. So Jenkins hopped on a Zoom call to speak with Ryder and Flanigan about what it’s like to release a film during a global pandemic, and how they’ve become the modern-day Thelma and Louise. He even managed, at the end, to make them smile. —SARAH NECHAMKIN

———

BARRY JENKINS: You guys see my background?

TALIA RYDER: I was trying to figure out how to do that. I wanted to make it look like I was at the beach.

JENKINS: To begin, I should say I’m not a journalist, so this won’t be as awesome as other interviews you guys have done. I’m just preparing you for that. But I thought it would be cool to finally get to meet you guys over the interwebs since I wasn’t able to be there during production. It’s a pleasure to meet you all. How are you doing?

SIDNEY FLANIGAN: I’ve been a little stir-crazy sometimes, but at the same time, it’s been a nice time for some reflection, I suppose. A little quiet.

JENKINS: It’s interesting because you guys were on this rocket ship with the film. It did great at Sundance and then, holy shit, like, amazing at Berlin. And now you kind of have to hit pause and reflect on what that was like. I’m just curious how you guys have been looking back on the past few months with the film. Have you been keeping tabs on how people have been responding to the release?

FLANIGAN: Yeah. It’s completely uncharted waters for me in general, especially doing it in this situation. It’s like, every day for I’m in my apartment and everything feels quiet, but there’s so much going on with this film at the same time. I know there’s a lot happening, but it’s hard to really feel and process all of it when you’re not out at the premieres and stuff, feeling all the energy. But there have been people messaging me on Instagram and telling me how much they like the film, and it’s been really nice that we’re getting some warm reception and support. I’m just taking it a day at a time now.

Sidney Flanigan. Photo by Victoria Stevens.

RYDER: I’ve gotten a lot of really nice DMs from girls my age telling me how much they’ve loved the film and how they haven’t really seen stuff like this before. That’s been really cool. I kind of expected after Berlin and Sundance that I would go back to school and feel normal again, and it went completely the other way.

JENKINS: It be like that sometimes. Before you guys read Eliza [Hittman]’s script, were you aware of all the procedures involved in a young woman going through what Sidney goes through in the film? Or was it an education for you guys?

FLANIGAN: I definitely learned a lot from the film. I’d always been aware of the stigma around the situation, but also, growing up in New York, I never worried too much about the obstacles that are in this particular film. I didn’t realize that some places require consent, and you might have to go in front of a judge to tell you whether you’re mature enough to make that decision. And that so many women actually travel that far and that there are these crisis centers in place that are misleading to persuade women—it’s just really wild to learn how much is put in place to make it more difficult.

RYDER: It was the same for me. I realized it was hard for women in more conservative states to have an abortion, but I didn’t realize how many things were in their way.

JENKINS: Sidney, you’re a little bit older than Talia, correct?

FLANIGAN: Yeah. I’m 21. She’s 17.

JENKINS: What’s cool is that when you watch the film for the first hour, Skyler seems older than Autumn. She’s sort of being the big sis, or the big cousin. Then, toward the end of the film, once Autumn starts going through the journey, it kind of shifts. I thought it was a really lovely thing you guys did in your performance. How well did you guys know each other during filming?

FLANIGAN: I felt like I really connected with Talia when I first met her when we were casting for her role. Eliza left the room for a second and we were all just sitting there and we got to talking a little bit, and we found out we were both from Buffalo originally. Having that shared hometown helped create this initial connection, and then Eliza gave us these bonding exercises. She gave us these journals and writing prompts, and they had some pretty personal questions. We wrote our answers and shared them privately with each other. There was a bit of a heaviness to it—I felt like there weren’t really any walls there anymore. We had opened up this ability to really connect with each other, and then over time on set, I just felt really close to her. I really love Talia. I think she’s a great person, and I’m glad to know her.

RYDER: I felt as we were filming that if the situation was in real life, I would have gone to the same measures for Sidney that Skyler did to protect Autumn.

JENKINS: I think the way that Eliza makes her films probably influenced that as well. Watching it, especially as a filmmaker, you get the feeling that it’s just the two of you guys carrying this luggage through Manhattan. If I saw two young women who look like you guys dragging that luggage at three in the morning, I would think, “Man, somebody needs to help those girls.” I know that a lot of the people in the background were real people, so I imagine it purposely fused you guys together in this way, where you kind of had to hold onto each other because Eliza couldn’t come in and tell everybody, “Hey these are my actors, don’t bump them, don’t touch them.” What was it like getting out in the real world as these characters, with these people not knowing that you’re making a film?

FLANIGAN: It was a little strange. For the most part, though, the cameras were pretty close to us, and people could see that and I feel like for people in New York, it’s kind of a normal environment. They don’t really stop to stare. But since it was my first time being on a set, it did already feel sort of alien. It kind of made me feel like the characters do in New York—an overwhelmed, “this is all so new” type of feeling.

JENKINS: And Talia, you went on to do [Steven Spielberg’s upcoming adaptation of] West Side Story from this, which is a very different set than Eliza’s sets. How alien was that for you?

RYDER: Well, this was my first movie, too, so it felt pretty alien to me as well. I was lucky that going to West Side Story, I didn’t feel like such an alien. The scene that we did going into Planned Parenthood with the protest going on—navigating that, we kind of had to hold onto each other. That was a very real moment because all the protestors were real and the stakes were not made up. Everything was happening right in front of us.

JENKINS: I was watching the film again this morning, and the way that you guys look at each other is really interesting. I love the way actors work with their eyes. There’s a very sweet moment when you first get to New York and you’re on the subway, and Skyler is watching Autumn, and you can tell in the eyes that she’s trying to figure out if she’s okay. Everything about it felt so intimate. It is a movie about a very serious issue, but it also felt like a movie about friendship.

FLANIGAN: I think it was important that Talia and I created our own bond offset that would kind of leap through onscreen.

RYDER: Building our own friendship was really important in the rehearsal process. When we started going through the script and the scenes, Eliza had Sidney and I do each other’s makeup. She said it created a more intimate bond when doing the scenes. I would have never thought to rehearse that way, but it helped a lot.

JENKINS: Sidney, in this film you sing a song in karaoke. Did you choose your own song and did you choose to sing it in the way that you sang it because you’re also a singer/songwriter in your own right?

FLANIGAN: I got to choose the song from a few options because music licensing is expensive. I remember seeing that song in there [“Don’t Catch You Crying” by Gerry and the Pacemakers], and I was like, “Oh my god, I’ve loved this song for years.” When it came to performing it, I wasn’t necessarily performing it as my character would perform it. Eliza was like, “You have to try and do it more like Autumn would.” So I changed it up.

JENKINS: Talia, I was curious about your wardrobe. How did you and Eliza arrive at how Skyler would dress?

RYDER: In our fittings we had a couple of different options, but they were all kind of the same vibe. I think Skyler wants to be a little more edgy, make some statements with what she’s wearing. I don’t think you saw it in the film, but in some of the scenes, I’d be wearing this really, really tight neon bra. I was like, “Oh, this is so Skyler.” She’s a bold character.

JENKINS: A small-town kid who wants to stick out in the big city.

FLANIGAN: Actually, the costume designer had gotten a lot of inspiration for the costumes from looking at Instagram pictures of girls from the town we shot in.

JENKINS: You guys are both very young people. I’m going to say three words—I want you to tell me if they mean anything to you: Thelma and Louise.

FLANIGAN: I’m familiar, but not as familiar as I’d like to be. I’ve never seen it.

JENKINS: Talia, do you know what the words Thelma and Louise mean?

RYDER: I feel like I should. I’ve heard them before. I wish I knew more.

JENKINS: Thelma and Louise is a film from the ’90s about these two women who are a bit older than you who go on this journey. It’s an awesome film, I think you guys should watch it. I don’t know any people as young as you guys, but I think your movie is kind of like Thelma and Louise for the present day. Even down to that dipshit kid that you guys run into on the bus—that’s kind of how Brad Pitt gets introduced to the world in Thelma and Louise. Next time I talk to you, I want you both to have seen Thelma and Louise.

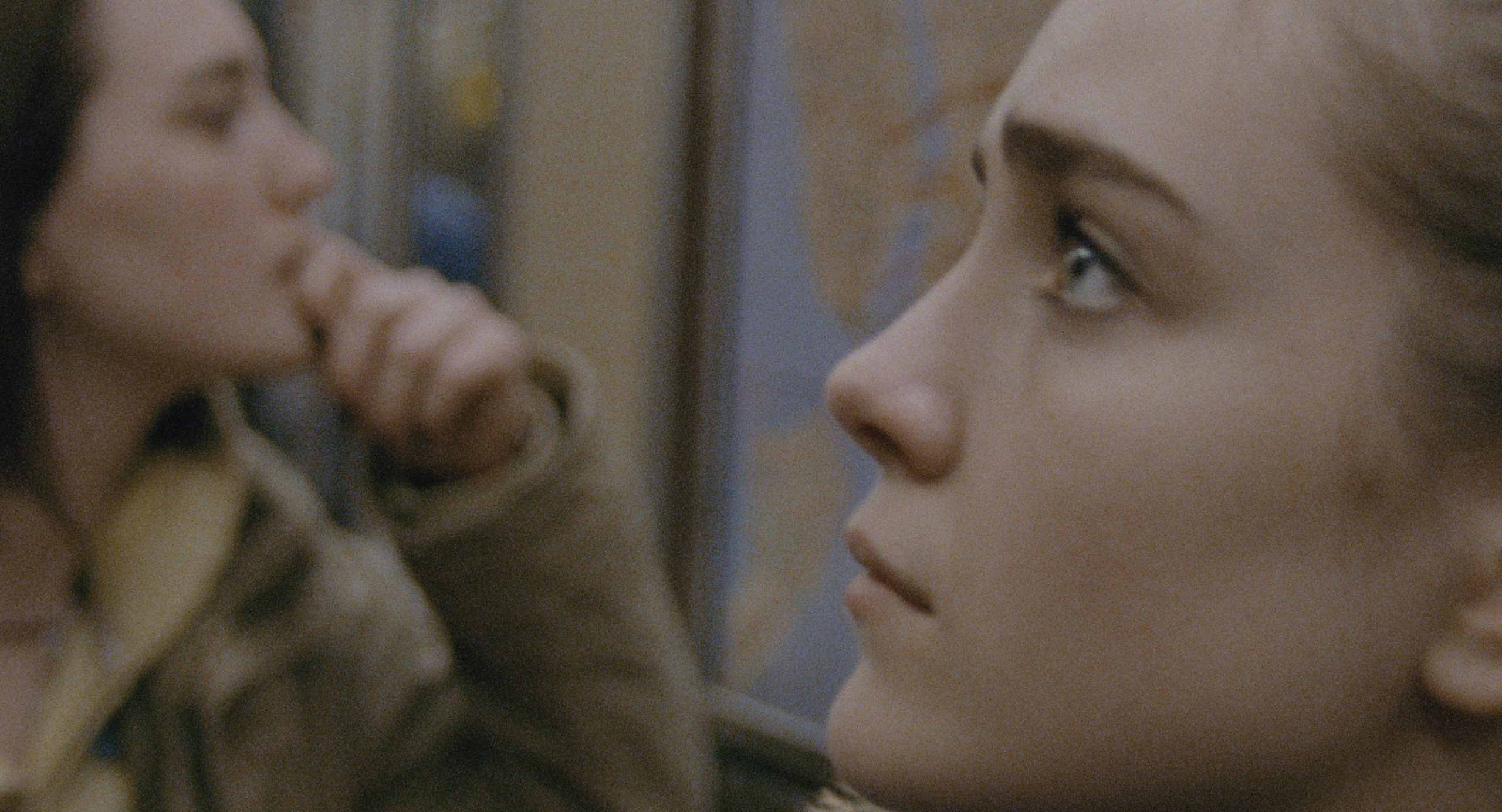

Flanigan and Ryder in Never Rarely Sometimes Always.

I wanted to use that as a segue to talk about what it means for the film to be released on VOD right now. I’m at home, Sidney’s at home, Talia’s at home, Eliza’s at home. Everybody’s at home right now. And I think there is some value in that because we don’t get to see these depictions of female friendship, especially for people in your age group. Right now, everybody’s sitting at home trying to figure out what to do, what to watch. This movie is a beautiful example of what young people could be watching. Talk to me about that process of going from the theatrical release, being at Berlin, to now having the movie live on VOD.

FLANIGAN: It felt like a quick jump because we were doing all these festivals, all this press, and it was all exciting. I remember then, after our week in New York, I came home and I was supposed to have a premiere here in Buffalo with all my friends and family, and I was really looking forward to that, and it was starting to look unsure whether we were going to still do it. There was a lot of emailing. We were like, ‘Maybe we’ll cut it down to 100 people,’ and the day before, it just got canceled.

RYDER: It was pretty disappointing that it wasn’t going to have the theatrical release that was initially intended. Personally, I think it’s a film that would just look so much better on a screen like that, watching it in a movie theater where you’re completely invested and there’s no distraction from your phone or anything. But I hope that with the VOD release it can reach a lot more people because right now people aren’t doing anything, and abortion laws are even more under attack. People are using the virus as a way to restrict women even more. I hope that as many people as possible can see it.

JENKINS: I’m speaking to you now as a random person, not as an executive producer. I was in production for 112 days—I didn’t get to go to Sundance, I didn’t get to go to Berlin, I didn’t get to go to any test screenings. So I never got to see the film in a big movie theater. I’ve only seen it on my 60-inch television in the back room, and it was still awesome as hell. And for anybody who watches it at home, it’s still going to be awesome as hell. But even more than that, I made a film called Moonlight a couple years ago—

RYDER: I love Moonlight, by the way.

FLANIGAN: Me, too.

JENKINS: Thank you very much. I love Never Rarely Sometimes Always, by the way. And there were quite a few people who told me that they didn’t see the movie in theaters because they didn’t want anyone to know that they were going to go and see it.

RYDER: Why is that?

JENKINS: Because they didn’t want anyone to assume or think or know that they were gay.

FLANIGAN: Wow.

JENKINS: And I also feel like there are young women who might be going through the same things that Sidney is going through who wouldn’t feel comfortable going to a theater to see the film, who might now be able to watch it in the comfort of their own homes. So trust me, the movie is playing literally anywhere that someone has a laptop, a phone, a television, and I really do believe that people are discovering the film in this form. The work you guys did and the work that Eliza did is still as gargantuan as it would be in a 500-seat theater. So be proud of it, all right? Cool?

FLANIGAN: Thank you. I appreciate that perspective.

JENKINS: A friend of mine went and saw Moonlight in a theater, and there were five people in the theater, and there was this one guy who was crying his eyes out. He sits through the entire credits, the lights come up, he stands up, and goes “gay ass movie” and then walks out. Just in case anyone saw he was in there.

FLANIGAN: Oh my gosh. Wow.

JENKINS: We made the work and he was able to engage with it, but he still wasn’t comfortable engaging with it. I feel the same way about the issues in this film. Talia, you hit on something that I think is really important as well. We’re all at home, COVID-19 is the only thing that people are thinking about or talking about. But while that’s happening, there are all these states that are trying to further restrict the rights of women like Autumn. You guys are a part of this piece of art that right now is very relevant. Tell me what that feels like.

FLANIGAN: It’s been a wild experience ever since I came home from making this movie, because that’s when I started seeing the news about the heartbeat bill. I was like, “Wow, I just came home from making this movie about abortion, and not too much longer I’m hearing about the Supreme Court case.” And now, with COVID going on, they’re relentless in trying to take away reproductive freedom. It makes women feel so powerless. This whole patriarchy thing, it’s so weird. Women have been resisting it for so long and it feels like this never-ending battle. Women carry that trauma generationally. It’s so heavy. So the film, I feel like, is going to be relevant for a very long time.

RYDER: I agree. It’s a huge honor to be a part of telling this story that I feel is so important. Eliza was saying she’s not trying to change anyone’s minds or cause an uprising or anything, but I hope people that watch this that may not agree with abortion can just empathize with the characters as people. People that say they don’t believe in it—I don’t think they have had a chance to really empathize with those people because they don’t know. They make assumptions. I hope people can walk out of the movie with a different perspective.

JENKINS: I’m curious if you guys had any advice for someone who might be going into their first feature film role. The dos and don’ts—what would you do and not do if you could go through the process of making this film all over again?

FLANIGAN: Oh, man.

JENKINS: You’re like, “I did everything right.”

FLANIGAN: I guess I’m trying to navigate it because it was really a whirlwind and a flash sometimes when I look back. If I were able to give myself advice, maybe I’d say to believe in myself a bit more and be more confident and to not compare myself to other people so much.

JENKINS: Alright, that’s all I got. I’m not going to talk about Insane Clown Posse. Not going to talk about it, not going to talk about it.

FLANIGAN: I’ve been trying to make it very clear to people that I myself am not a juggalo. I just happened to be at a wedding.

JENKINS: I just wanted to make you smile at the end of this interview. That’s all.