Rough draft

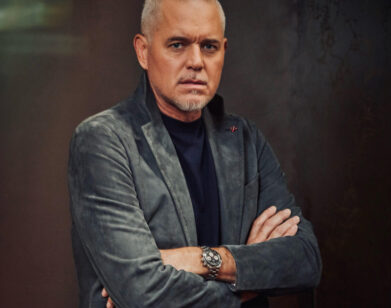

Melissa Febos on Her Literary Inspirations, Writing Habits, and Notebook Fetish

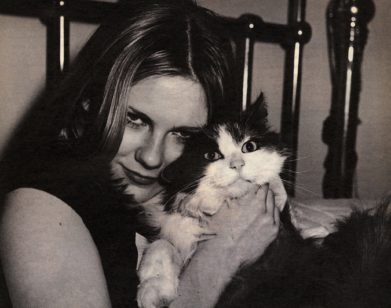

Photos by Melissa Febos.

This is Rough Draft, in which our favorite writers get to the bottom of their own craft. From preferred writing drinks to whether or not you really need to carry a notebook, we find out all the ways they beat writer’s block and do the work. Before curling up with Girlhood, Melissa Febos’s new collection of personal essays, discover all the elements that helped her get it done.

———

JULIANA UKIOMOGBE: Describe your ideal writing atmosphere. What gets you in the mood?

MELISSA FEBOS: A long sumptuous day in which I don’t have to do anything but read and write. Reading the right thing gets me in the mood, which usually means something that makes more seem possible—often passionate, surprising writing, and beautiful sentences. Recently, that has been David Adjmi’s ecstatic memoir, Lot Six, Elissa Washuta’s White Magic, Lydia Millet’s A Children’s Bible, Melissa Broder’s Milk Fed, Forsyth Harmon’s Justine, and Natasha Trethewey’s Memorial Drive.

UKIOMOGBE: Do you eat or drink while you write?

FEBOS: I do not eat while I write, but I usually have a non-alcoholic beverage (or two or three) nearby: coffee, tea, water, and most often seltzer. At the end of a long writing day, my desk is littered with empty seltzer cans like the detritus of a really wholesome bender.

UKIOMOGBE Do you keep a notebook and/or journal?

FEBOS: I keep so many! Like lots of writers, I’m a bit of a notebook fetishist. I like different notebooks for different things. I have a slim one with subtle graph paper that is designated solely for lists. I keep spiral-bound Decomposition Books for morning pages and have a library of them going back over ten years that also functions as an archive that I rely upon when reconstructing past timelines while writing (I have a pretty unreliable memory for some things, which is trouble for a memoirist). I use steno pads for taking notes during meetings or sketching out my ideas for an essay or lecture. I could go on and on, and don’t even get me started on pens.

UKIOMOGBE: What’s your favorite quote?

FEBOS: “It is joy to be hidden and disaster not to be found.” —D.W. Winnicott

UKIOMOGBE: Whose writing do you always return to?

FEBOS: Siri Hustvedt, Audre Lorde, Jeannette Winterson, Anne Carson, Toni Morrison—so many!

UKIOMOGBE: What books did you read as a kid/teen? Have your thoughts about the writers changed?

FEBOS: I read everything I could get my hands on as a kid: poetry, thrillers, romances, YA fiction, poetry, erotica. My favorite novel in my teens was [J.D.] Salinger’s Franny and Zooey. I loved that it was at once very funny and also profound; it was intellectual, emotional, and spiritual. I also probably read Rita Mae Brown’s Rubyfruit Jungle twenty times. I devoured stories about anyone queer, addicts and alcoholics, sex workers, memoirs of madness—I was obsessed with all kinds of outsider narratives.

My first idea about writers was that they could be misfits—totally debauched or unhinged or simply strange—and still have a role in society, which was a huge relief for me. I could not imagine doing anything but reading and writing for my whole life, nor could I imagine any other occupation that would be capacious enough to hold all that I was: queer, passionate, compulsive, ultra-sensitive, fanciful, sexual, secretive, and seemingly unable to maintain focus on anything that didn’t interest me. I think I knew on some level that I was a nascent drug addict, too, and being a writer appeared to be one of the few professions that would still have me in that case.

It turned out that I was indeed a drug addict, but also that getting sober was the best thing I ever did for my writing. Sobriety and writing go together much more beautifully than addiction and writing did. I was correct in assuming that it was a perfect occupation to hold all of my weirdnesses, and it has also helped me find a community of folks who share them.

UKIOMOGBE: Do you read while you’re in the process of writing? Which writers inform your current work the most?

FEBOS: Oh, yes. I’m always reading a combination of research material and writing that inspires me. For my current project, I’ve been reading a lot about female saints from the Middle Ages, lesbian separatists, trauma theory, as well as all sorts of surprising nonfiction—books by Anne Boyer, Renee Gladman, Brian Blanchfield, Lily Hoang.

UKIOMOGBE: How many drafts of one piece do you typically write?

FEBOS: Always more than I hoped would be necessary.

UKIOMOGBE: Who’s your favorite screenwriter? Can a movie ever be as good as the book?

FEBOS: I don’t have a single favorite. I love Jane Campion, Guillermo del Toro, Barry Jenkins, Lisa Cholodenko. A movie can be a completely different kind of good from a book. I think every piece of art succeeds on its own terms, so comparing them doesn’t really make sense to me.

UKIOMOGBE: Do you consider writing to be a spiritual practice?

FEBOS: Absolutely. All the definitions of the word “spirit” convey fundamental elements of the writing process for me—the essential nature of something or someone, the soul, ghosts, to carry or be carried away, emotions—but I would also say that as someone without religion, I have found a kind of church in art. A lot of the things that folks seek in religion, I find in and by way of my creative process. I cannot imagine my life without it.

UKIOMOGBE: Which writers would you choose to have dinner with, living or dead?

FEBOS: I suspect that it’s better to let my heroes stay wherever they are, living or dead, so that I can keep simply worshipping their work. Especially after this past year, I’d choose to have dinner with my own beloved writer friends instead.

UKIOMOGBE: What advice do you have for people who want to be better writers?

FEBOS: Read with your whole mind open. Cultivate persistence and curiosity. Find a way to separate your relationship with your writing from your relationship with publishing, and all of the professional aspects of being a writer.

UKIOMOGBE: What are some unconventional techniques you stand by?

FEBOS: A common piece of writing advice for those who write from personal experience is to wait a long time before writing about a subject, so that you can acquire the necessary perspective, the insight that comes with hindsight. While I understand the logic undergirding that advice, I have often written my way out of experiences. Without hindsight, I’ve been left with other tools, often more lyric modes of articulating my experience and that has yielded writing that I couldn’t have produced at any later time. Writing is my best way of thinking, of coming to insight about my experiences, and mostly I prefer to do it sooner rather than later.

UKIOMOGBE: Can great writing save the world?

FEBOS: It’s less the world that needs saving than humankind. In most cases, I don’t think writers are saving anyone but themselves, maybe a few desperate readers, but that’s no small thing.