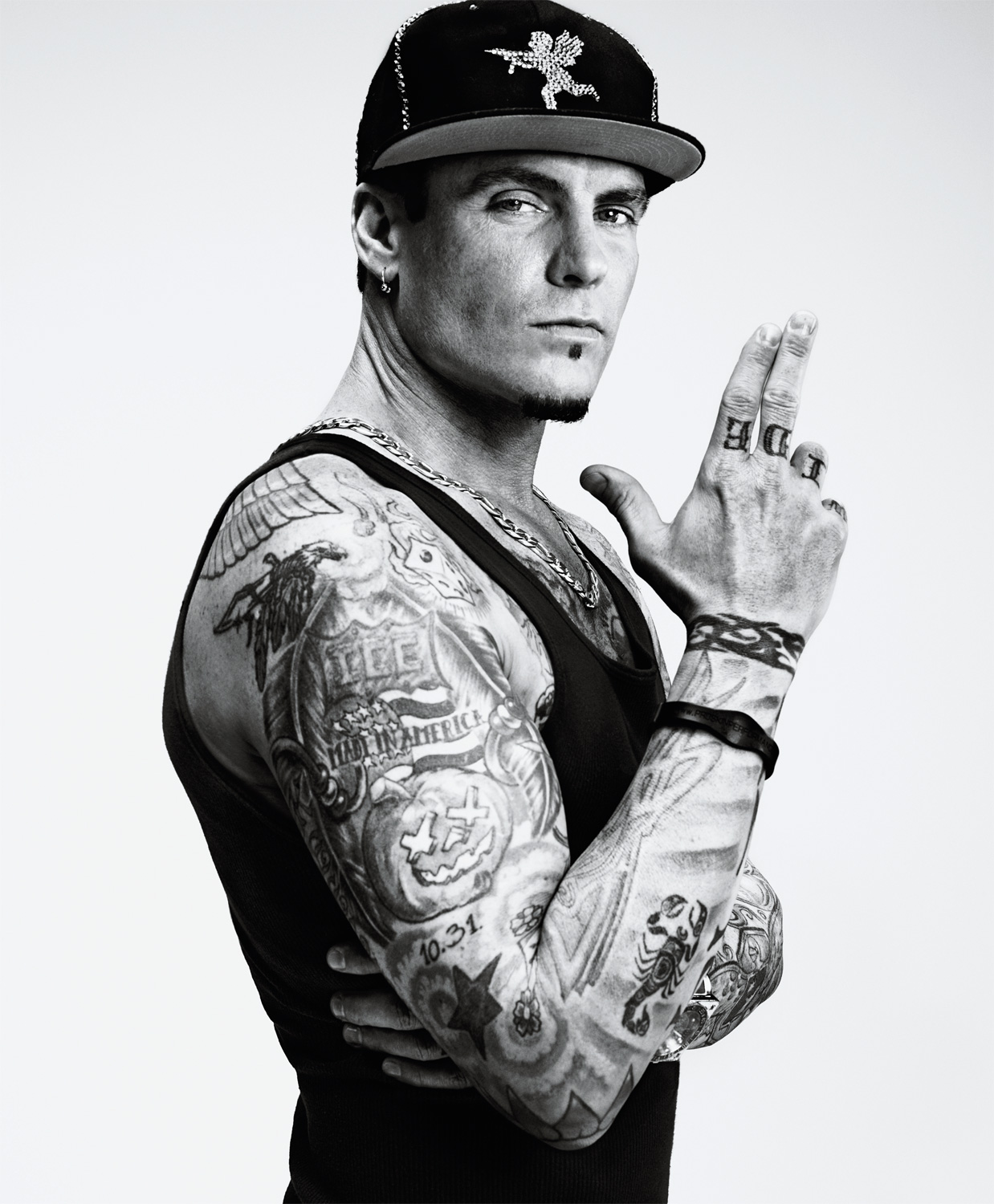

Vanilla Ice

If you haven’t been paying careful attention, you might be forgiven for thinking that Vanilla Ice’s career began and ended with his hit 1990 single “Ice Ice Baby,” off his major-label debut, To the Extreme.But just because none of his subsequent albums achieved the heights of that record, Ice, born Robert Matthew Van Winkle, is no one-hit wonder. While his own music has shifted increasingly toward a less mainstream, more hard-rock sound, the Miami- born performer and entrepreneur has found many outlets for his talents.

It hasn’t been easy. Over the years, Ice has taken a brutal beating from critics, and, in 1994, during a downward spiral of drugs and alcohol, even attempted suicide. But America loves a second act. If his appearance in the 1991 movies Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles II: The Secret of the Ooze and his own starring vehicle Cool As Ice were less than Oscar caliber, Ice has nonetheless proved resilient, persistent, and enduringly popular. More than just a trailblazer for frosted-tip, hair-gelled white rappers, he has proven himself to be a natural in the age of reality TV. After a stint on VH1’s The Surreal Life, he began hosting The Vanilla Ice Project on DIY Network, in which he appears as a tattooed gangsta version of Bob Vila, revamping and flipping Florida mansions. More recently, the energetic 43-year-old began proving that the second part of his moniker is more than just an empty claim to cool, performing on the hit U.K. series Dancing on Ice. (His years of motocross also came in handy for the show, helping him maintain his balance on slippery surfaces.)

This summer, Ice begins work on the upcoming Adam Sandler project I Hate You, Dad, in which he plays the role of Sandler’s rock star friend. His latest album, the independently released WTF, will also be unveiled in the next few months. Ice, who currently lives in Port St. Lucie, Florida, spoke with us by phone from Madame Tussauds in Manhattan, before flying to England, where he is set to appear in a live stage version of Peter Pan this December. WTF indeed.

DIMITRI EHRLICH: Where are you?

ROBERT MATTHEW VAN WINKLE: I’m at Madame Tussauds in New York. They’re doing a man cave here [for the DIY Network show Man Caves].

EHRLICH: Sorry. What’s a man cave?

VAN WINKLE: Any kind of room that men would gravitate to.

EHRLICH: Speaking of which, how did Adam Sandler wind up casting you in his new movie I Hate You, Dad?

VAN WINKLE: He told me he was laying in bed with his wife and they were watching The Vanilla Ice Project, and she said, “You should get Vanilla Ice in one of your movies,” and he called me.

EHRLICH: I saw him once near my apartment in New York, and he was just talking to a homeless guy sitting on, like, the ground.

VAN WINKLE: That’s great! When I first met him he had these old sneakers on and his office was kind of a mess. He had his old grandpa’s recliners in there. It was just great, real warm, and comfortable.

I had a weekend that lasted a few years back in ’94. I didn’t know who I was, and as far as the quote unquote dream of being a rock star, rich and famous, it just wasn’t as good as the dream.Vanilla Ice

EHRLICH: Tell me about your experience with the U.K. television show Dancing On Ice. I know you used to breakdance as a kid before you had a career as a rapper. But I assume dancing on the ice is a different challenge.

VAN WINKLE: Yeah, I’m trying to learn to skate and do all my same moves with skates, which is very difficult on ice. Apparently they find that veryentertaining over there. It’s entertaining to watch a celebrity get out there and crash, you know? Actually, I had a bad crash, fell over and got four stitches in my eye, got blood all over my face, and I got a concussion and it hit the tabloids, it hit all the news. But when I learned my big spin and my great dance move and didn’t crash, it didn’t hit the tabloids. [laughs]

EHRLICH: How did you start breakdancing?

VAN WINKLE: My breakdancing crew used to go to the mall and squat a piece of cardboard there; we had our jam box, and I’d spin on my head and make about forty bucks a day, which was pretty good back then. I was only 14 years old, so I would chase the girls around the mall and eat some pizza and have some change left over. I’m from the poor side of the tracks, and I made more money doing that than my rich friends got in allowance. [laughs]

EHRLICH: Tell me a little more about The Vanilla Ice Project, your reality show about fixing up houses. What drew you to that?

VAN WINKLE: Actually, I did a bio for A&E, and one thing one of the producers picked up on was that I do real estate. It’s kinda boring, and I didn’t think anybody would really care about that, but a year later I get a phone call and a producer asked, “You still do that?” And I said, “Yeah. I have a seven thousand square-foot mansion I just closed on yesterday, and I’m gonna renovate it. It’s been sitting for three years. It’s a foreclosure type thing. The pool is black, it’s been raped of all the appliances and cabinets, and the toilets are gone and everything, and he said, “You gotta be kidding me. Do you mind if we film it?” And I said, “Not at all. Come on and film it.” And there you have it. It actually came together in two days.

EHRLICH: Were you doing that to flip the house? Or is that where you were going to live?

VAN WINKLE: Oh no, no, no. I’ve been flipping homes for 15 years now. When I came into a lot of money, I bought homes all around the country. I went on tour for three years, never used them, and I’m like, jeez, you know? I bought these homes, and I haven’t used them once. And I ended up selling them, and literally I made millions of dollars on selling them, I’m like, “Are you kidding me? I just sold these homes I hadn’t even used. I mean it can’t be that easy.” And it was. So I’m like, “Fuck. I’m gonna invest in real estate.” So I just bought a whole bunch more houses and sold them.

EHRLICH: In case the IRS reads this article, we better not talk too much about the money. These days people are getting cleaned out in real estate—are you finding it more difficult?

VAN WINKLE: It’s better right now than ever. I’m cleaning it up right now. Even in a bad market, location, location, location is a way to still buy and sell property. And with these short sales, there’s so much inventory out there. I’m telling you, it’s better today than it’s ever been.

EHRLICH: Once we get off the phone, I’m going to go buy a house. You’re inspiring me. Switching gears, let’s talk a little about Canada—one of my three favorite countries in North America. Tell me about Canada Sings! What is that?

VAN WINKLE: Basically, you take these people from working environments, and they’re given professional choreographers and vocal coaches, and they’re taught to sing and put this act together. But the thing that makes it so amazing is that they are doing it for charity. Each team has a special connection with the charity. Like one of the guys who’s on the team is giving to the Ronald McDonald House because he just gave his kidney to his daughter and was put up in the Ronald McDonald House. So there is a whole story behind each team of how they are personally connected to the charity that they’re competing for. So it’s kind of a tearjerker, but it’s amazing.

EHRLICH: And you have a new album, WTF, which I assume stands for wisdom, tenacity, and focus, or is it “what the fuck?”

VAN WINKLE: No, it stands for wisdom, tenacity, and focus. That way we can get it in Wal-Mart. [laughs] Just kidding. It doesn’t have any explicit lyrics. It’s a total change of direction for me and a new musical adventure. It’s been really fun doing it because, you know, you get bored doing the same old thing. So I changed it, flipped the script a little bit, and put a techno, hip-hop dance record together, and I’m really proud of it, man. It’s like Prodigy meets Lady Gaga meets Vanilla Ice.

EHRLICH: I’m also a songwriter, and one of the people who recorded my songs is Moby, so I should have gotten him on that record. Moby and Vanilla Ice.

VAN WINKLE: Oh, I love Moby. Oh, that’s great, absolutely. You never know.

EHRLICH: You’re also going to be appearing as Captain Hook in a live stage production of Peter Pan in England.

VAN WINKLE: Henry Winkler played it one year, Hasselhoff played it last year, I’m playing it this year, and, with the success of the show Dancing On Ice, there is a lot of attention over in Europe. In fact, actually, I’m flying back to London today—I’ve been living there for the last year.

EHRLICH: I know that you felt that some people you’ve worked with in the past did a bad job in terms of representing you. Do you ever have any regrets about the name or persona you created as Vanilla Ice, in terms of, like, things that were your own responsibility?

VAN WINKLE: Well, yes, tons of regrets, but I look at those like positives. The whole way the thing played out was so huge, more massive than I ever predicted. I sold over a hundred million records worldwide, all my records combined. The way I look at it is, “We are who we are because of who we were.” Meaning that anything that’s happened in my past is a great thing. I turn my negatives into my positives because one of my mottos is, “Yesterday’s history, tomorrow’s a mystery,” meaning that you can’t go back and change anything in the past. I had a weekend that lasted a few years back in ’94. I didn’t know who I was, and as far as the quote unquote dream of being a rock star, rich and famous, it just wasn’t as good as the dream. Another car is not going to help me out, a nicer car, I’ve already got it. A bigger house ain’t gonna do anything for me, and you know, a yacht, it’s not going to do anything for me anymore. So how can I find happiness? Well, you know, you think of Britney Spears, she shaves her head, she goes crazy. It’s hard for us out here—I don’t need a violin or anything, but I didn’t know what my purpose in life was. I had people come over to my house and break a five-thousand-dollar vase and go, “Sorry man, where’s the beer?” You know? It’s just fake, artificial, and just wasn’t real, so I’m like, “This sucks, man,” and that was my weekend that lasted three years. I found my purpose, which is family and friends, and that’s why I look at all my negatives as positives, because it’s helped mold who I am today. And even though I wouldn’t wish my life on my worst enemy, to get to where I’m at today, I wouldn’t trade it with anybody ’cause I’m so grateful where I’m at, and even though I had to go swim through the trenches to get to the other side, I made it to the other side and it’s very rewarding. The most valuable lesson I’ve ever learned in my life is that life is about family and friends, not about material things or any of that. It’s about enjoying your life. If you have no family, no friends to enjoy it with, it don’t matter how much you have, how much success you have, how much fame you have, how much money you have, it doesn’t matter.

EHRLICH: Can you still walk down the street without being recognized?

VAN WINKLE: No, absolutely not. It’s probably worse today than it ever was back in the day. I guess it’s ’cause I’m on television a lot more. I can’t go to the mall. I can’t go down the street in New York City. It gets overwhelming, but it doesn’t bother me, because I have a whole new outlook on it. I don’t run around with bodyguards. That’s why I think The Vanilla Ice Project is such a success, because people get to see the real side of what I’m like, aside from the famous, bigger-than-life Vanilla Ice onstage persona. The Surreal Life was all staged, so when you see The Vanilla Ice Project, you see the real deal. It’s not a reality show, it’s cameras watching me be myself. Here’s my daughter, here’s my wife, here’s my kid, here’s what Rob really is. I always try to live a private life. I don’t run around L.A. and call the paparazzi like Britney Spears when she goes to Starbucks. I don’t do all that shit—I’m far away from that. You know, I’m a regular family guy.

EHRLICH: Do you find there’s any difference in general in the way black and white people view you today as opposed to when you started out?

VAN WINKLE: Oh absolutely. We all embrace each other now. I think America has evolved into a greater place, becoming one with equal rights, and as a musician, I had a lot of hurdles when I first started to get respect, just being white. When I first started, my whole audience was black. I always intended it to be black because that’s what rap music was back then.

EHRLICH: Where do you see yourself 25 years down the road?

VAN WINKLE: One thing I’ve learned to do is to expect the unexpected. Everything that has hap- pened in my life has come out of left field. So I have no clue. I have goals and agendas, but I have no clue where I’m going to be. [laughs] If you asked me the question 10 years ago, there’s no way I could have pictured myself ice-skating. I’m from Florida. We don’t have ice, you know?

EHRLICH: You began your career as a performer on a dare when you went on stage at City Lights in Dallas. Does the idea of doing things on a dare still hold any appeal to you?

VAN WINKLE: Absolutely. I’m an adrenaline junkie, and I’ll just do it for the thrill of doing it. I’ve never had nerves get in my way of anything.

EHRLICH: I know you’ve been into motocross for a long time. How has the idea of extreme shifted for you as you’ve gotten older?

VAN WINKLE: I still live my life to the extreme, but I’ve definitely cut out the partying. I’m a family man. I wouldn’t want to disrespect them in any way or humiliate my kids. I don’t cheat on my wife. I don’t run around like Tiger Woods. I’m a vegetarian. I try to take care of myself now. I’ve been down some roads that were pretty self-destructive, and I learned not to go down those roads. At one point in my life, I didn’t even know who I was, what my purpose was, and didn’t even want to live anymore. With hundreds of millions of dollars in the bank, I didn’t give a shit about life. Who I am today is a complete flip-the-script opposite of that and just super-grateful, man, for my family, for my kids. And that’s the meaning of life, man, the true meaning of life. I still race moto-cross, I still jump over monster trucks on fire. I stilldo wild things, but I don’t party. I don’t drink, I don’t do drugs. I try to stay as clean as I can, butI just jumped a 1967 Cadillac through a fire and into a pond. I did that for charity. I love doing the stunts.

EHRLICH: So you’re the non-evil Knievel.

VAN WINKLE: Yeah. [laughs]

EHRLICH: In the early ’90s, the infamous rap industry tough-guy Suge Knight allegedly paid you several visits, to intimidate you into signing over some of your songs to him. What do you remember about those encounters? Did you feel physically threatened? I believe the story was that at one point he took you out on a balcony implying that he might throw you over the ledge.

VAN WINKLE: Yeah, well, first of all, that’s a lie. I read the story, and I heard it, and I had to defend it nine million times, but he never took me to the balcony, threatened to hang me over, or anything. In fact, the guy didn’t have to be mean or anything, I got it. Rap music is gangster, it’s been gangster from the beginning. Um, I did go to a balcony, so there is a little bit of truth to it. Um, yes, Suge Knight took some money from me, and he did take me to the balcony, explained it to me. He was actually nice to me. It’s completely different than the story that’s been posted out there in the media. I look at it like I’ve invested in some of the greatest hip-hop music in the world. I mean, from the money that Suge got from To the Extreme from me, he started Dr. Dre. The Chronic record came from the funding from my record; Tupac came from the funding of my record; Snoop Dogg came from the funding from my record. It produced some great, historical hip-hop music and legends out there. So I gave back to my community that made me. I look at it like it’s a positive. I can’t go back and change that. And, to be honest with you, I’ve made great investments, so it ain’t like I needed that money. People look at it like, God, they think I’m so bitter about it—I never went to the police, I never did anything like that. I knew better.

EHRLICH: But when you say that was an investment, you didn’t get returns on the Tupac and Snoop records. In other words, you gave him money, so indirectly, you helped fund those albums, right?

VAN WINKLE: Indirectly, exactly. Indirectly I helped fund some of the greatest hip-hop music without a return on my money, but I didn’t care. Look, it was a price that I had to pay, and it’s funny how this story has evolved and been polished up and changed around to make him a monster and everything—hell, I’m still friends with Suge Knight. I never was bitter about it. But the way the story goes is that, like, he’s hangin’ me over some balcony and my change isfallin’ out of my pocket—you know, come on.

EHRLICH: Okay, well regardless of how hard Suge Knight can hit you, over the years you’ve definitely taken some pretty hard hits from the press. Did that stuff ever hurt? How did you handle the negative things that people wrote about your music?

VAN WINKLE: It was very emotional for me, very hard for me. I didn’t like it, of course, but, I just looked at it like, you know what? I’m sellin’ a million records a day; I gave them a record, they gave me tons of money. They’re sellin’ a million records a day, so I’m just goin’ along with it. I’m thinking, okay, I’ll just say hey, it’s workin’. Shit, man. Fuck, a million records a day? Hell, I got platinum yesterday, I’m double platinum today. [laughs] I’m thinkin’, All right, whatever. And, you know, there was a consequence to that. But I realized at that point, okay, I guess I’m a product on the shelf. So it was kind of a double-edged sword. They had to clean up the image to make it cross over, because if you really listen to the words of “Ice Ice Baby,” it says, you know, “Shay with a gauge, Vanilla with a nine.” You know what a gauge is. A 12-gauge shotgun, a nine is a nine millimeter. “The chumps acting ill ‘cause they’re full of eight ball.” That’s cocaine! You know? This is not for seven-year-old kids. The record company cleaned up my image, cleaned up the whole look, and then all of a sudden there’s this good lookin’ kid out there, and they made it acceptable for the parents because they saw these kids dancing—oh, it’s just a dance song, it’s acceptable now and let’s find out who he is. Oh, he’s wholesome, he’s good, and all this. But the truth was is that I wrote all of that. I’m not an artificial act, man, I’m not New Kids with snot, I’m not any of this boy-band shit. I came out of nowhere and I wrote all my words and all my lyrics. Once this whole mess started, there was no way I was going to stop it. I had no idea where it was going, but I had to ride it. Wherever that wave took me, that’s where I was gonna be.

EHRLICH: One place the wave took you was into a relationship with Madonna for eight months, which is documented in the book Sex. How did it end and are you still in touch with her?

VAN WINKLE: It’s really not very exciting. It was just kinda boring really ’cause it was just a normal relationship like anybody would have. I guess it’sfascinating because both people are famous, but to me it’s just another relationship that was really no bells and whistles, just another girlfriend that I had. I wish I could tell you something that would make it more exciting.

EHRLICH: In 1994 you grew dread locks for a period of time and started talking openly about smoking weed. Were the dread locks a sign that you were interested in Rastafarianism or was it just a fashion thing?

VAN WINKLE: No, I was totally interested in it and am a huge fan of old-school reggae from the ’50s and ’60s. That’s my main catalogue in my iTunes, and, yes, I used to smoke pot and advocate the use of it. I was just tryin’ to tell everybody to chill out because people who are on pot don’t kill people, you know? I was trying to send that little Rastafari thing out there. A lot of that has evolved into my life today because Rastafarians are vegetarian; I’m vegetarian. Bob Marley has so much wisdom, and his words to music are unlike any other musician, ever. So, yes, he’s a mentor to me. Yes, I’ve learned a lot from the Rastafaris, and their outlook on peace and life and love and unity is just amazing.

EHRLICH: When you look back on all the ups and downs of your life and career that we’ve talked about so far, as well as other things, how do you want to be remembered? If you could write the epitaph on your gravestone, what would it say?

VAN WINKLE: Here’s a guy with no ego that took it worldwide. [laughs] And survived.

Dimitri Ehrlich is a contributing music editor of Interview.