Steve Toltz’s Platonic Ideal

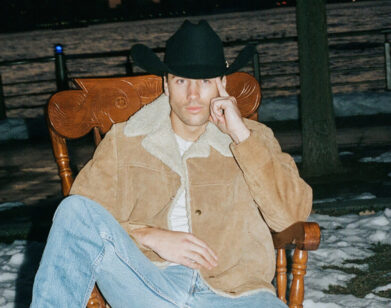

ABOVE: STEVE TOLTZ. PHOTO COURTESY OF PRUDENCE UPTON.

An abrasive ex-con, Aldo Benjamin is not the easiest protagonist to sympathize with. In Australian writer Steve Toltz’s new novel Quicksand, even the other characters find Benjamin’s behavior challenging, but throughout the course of the book, Benjamin draws the reader in.

Now in his early 40s, Toltz is known for his blend of philosophical musings and aphoristic humor. His debut novel about three generations of an eccentric Australian family, 2008’s A Fraction of a Whole, was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize. Quicksand, which comes out today via Simon & Schuster, is his follow-up.

JARED LEVY: You have a book tour coming up. You’re doing readings in the U.S. and abroad. What is it like to be done with the book and then do publicity?

STEVE TOLTZ: I’ve heard someone refer to an interview with Harrison Ford where he says something like, “The publicity is my job, but the acting I would do for free.” That’s accurate. I treat writing like a job, and I’ve struggled for the last 20 years to make it my livelihood, but it’s more like a trade. The publicity is the only part of the job where I have to wear pants. That feels more like a real job for me.

LEVY: What is your relationship to discussing your writing?

TOLTZ: In a way, the book speaks for itself. I’m unable to elaborate unless you’re talking about the origin to the story. When you’re in an argument with someone, you say, “Look, I don’t want to argue, I just want to say one thing,” and then you walk out of the room—that’s what writing is for me. I’ve said my one thing. I’ve walked out of the room. Now someone keeps pulling me back in to explain myself.

LEVY: To pull you back in, Quicksand communicates a lot through lists. What is the significance of lists for you?

TOLTZ: I love lists in poetry. Some of my favorite poets use lists. Saul Bellow has a quote that “a writer is a reader driven to emulation,” or something like that. For me, the whole act of writing is responding to literature that I love. A lot of that is stuff that I’ve read over the last 20 years and it’s engrained in me. When I’m starting to write, I’m referring to the best things that are in my head.

In a way, I don’t think about the reader as much as one might think. Perfection is unachievable, so what I’m trying to do is reach a platonic ideal of this imperfect form. If I knew no one was ever going to read the book, it would be exactly the same: the same kind of tension, pacing, and punch lines. The reader is both necessary, but also irrelevant.

LEVY: There are a lot of different writing styles in the book: poetry, stream of consciousness, and dialogue. Why are various forms of writing part of the platonic ideal of Quicksand?

TOLTZ: There are a few answers to that and none is completely true on its own. In my period of falling in love with literature, one of my favorite books was A Hero of Our Time by Mikhail Lermontov. What blew me away is that there’s one character that’s talking about another character, and it switches from first person to third person, and then into a diary. I love the variety of forms; what that book did is an interrogation of a character. When you’re trying to find out about a person, one of the best ways is to hear about that person from the inside and the outside.

That’s one answer. Another answer is that in this book the poem is the only section that is autobiographical. Like the character, I became paralyzed. I spent a lot of time in hospitals and in a wheelchair. And because I’m not a memoirist, I tried to write that as prose, but it didn’t work out. It wound up dead on the page. I don’t like to write things that are strictly factual. For me, writing is about invention at all times. Because I had nothing specific to invent, I had to put my invention into form. That’s why I wrote that as a poem.

For a long time, I wanted to find literature that was like Dostoyevsky or Tropic of Cancer. In those books, you’re very much aware of ideas and they’re very didactic. You know you’re listening to Dostoyevsky and you know you’re listening to Henry Miller. They’re not hidden in the characters. I have a natural storyteller instinct, which is very different. I love story where characters wander around and nothing happens, but I also love stories where a lot happens. So in order to marry all these different things that I love, the most effective way is to take on different forms.

LEVY: Another characteristic feature of Quicksand is that there are a lot of quick, witty lines. One mentions that you never see characters go to the toilet in movies. With this book, what was the equivalent of going to the toilet?

TOLTZ: As you grow older, you try to match blocks of time with other blocks of time. I went to university and got a bachelor of arts. I did three years there. Those were three influential years in my life and in the end I had this single piece of paper, which was my degree. With this book, the first three years I also had one piece of paper, and that was Page One. It wasn’t just throwing out stuff; it was this long torturous process of working out the book that I wanted to write, taking a character, and running with it. It changed so often.

It was also coming to terms with the idea that writing a Fraction of a Whole, which was my first novel, only taught me how to write a first novel. Then I realized that I had to learn how to write this book that I didn’t know how to write. Somewhere in Quicksand there’s a line like, “illness is only diagnosable after death,” like when there’s an autopsy and they’re like, “Oh, that’s why he died.” Sometimes the first draft is like that. So I would write a whole thing and then realize it died and it was only by finishing it that I could understand what was wrong with itself. It’s a time consuming thing to do and no way to make a living.

QUICKSAND IS OUT TODAY, SEPTEMBER 15, VIA SIMON & SCHUSTER.