New Again: David Hare

The 2015 Tony Award nominees were announced yesterday, and ahead in the race are An American in Paris (directed by Christopher Wheeldon, starring Robert Fairchild and Leanne Cope) and Fun Home (directed by Sam Gold, starring Michael Cerveris and Beth Malone), with 12 nominations each. Other nominated shows include Wolf Hall, a two-part British period piece, The Elephant Man, starring Bradley Cooper as a disfigured circus performer, and Skylight, a relationship drama starring Bill Nighy, Carey Mulligan, and Matthew Beard.

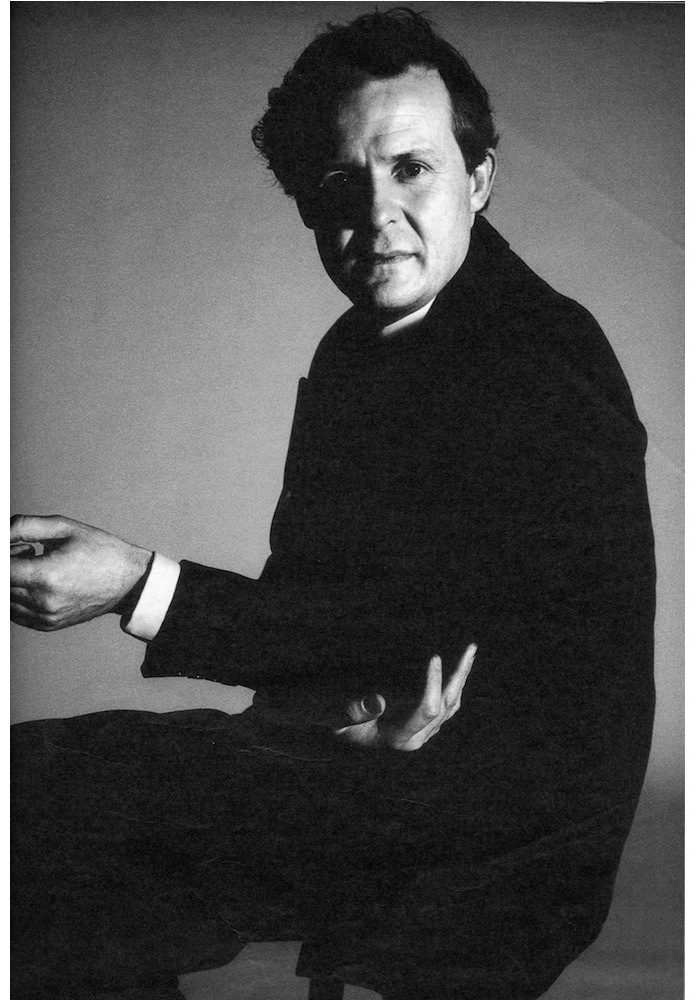

Written by David Hare, Skylight originally premiered at the National Theatre in London in 1995 with Michael Gambon and Lia Williams. Here, we revisit a 1989 interview with Hare in which the knighted playwright, screenwriter, and director discusses politics, the theater, and the Tony Awards. —Johanna Li

Dramatically Speaking

By Kathleen Tynan

One of Britain’s best playwrights, David Hare has two new films, Strapless and Paris by Night, and one new play, The Secret Rapture. Kathleen Tynan talked to him in London about directing, Orwell, and New York.

After I saw Knuckle in 1974, I made sure to book in for any new play by David Hare. It’s not only that I’m drawn to the views of his left-inclined university wit who grew up in the fringe theater and moved swiftly to the main arenas; nor merely that I’m eager to listen to a writer who cuts through the small talk to argue about, laugh at, and explore—in a piercingly intelligent yet light style—such matters as capitalism (Knuckle, Pravda), the Chinese Revolution (Fanshen), post-colonialism (A Map of the World), and the death of idealism (Plenty). It has more to do with recognizing a detective of the soul.

David Hare’s most recent play, The Secret Rapture, opened last October at the National Theatre in London. The Sunday Times calls it “a moral masterpiece for our times” and described it as “one of the best English plays since the war.” The Guardian wrote that it “touched profounder chords” than anything Hare had written before.

Last year, Hare explored the Thatcherite ethos in Paris by Night, starring Charlotte Rampling, and examined extreme romantic love in Strapless, with Blair Brown and Bruno Ganz. He wrote and directed both of these films, which will be released here later this year.

Not long ago, Hare dropped into my South Kensington living room and answered some questions. He is tall, extremely good-looking in a quintessentially angular, English way, articulate, witty, and playful. And yet, when grappling with such matters as God and mammon he suggests, as one observer put it, “an air of luminous exhaustion, like a Dominican monk lost in Gomorrah.”

According to his friends, he gets easily depressed, suffering from a strong sense of torment. (“You must find the dark,” he once instructed the actor Simon Callow.) His agent, the legendary Margaret Ramsay, describes him as “full of feelings, not able to control himself, and capable of making an ass of himself. But I love people who do really destructive things. Don’t you?”

Hare hardly gives the impression of self-destructiveness. He works extraordinarily hard; adores his girlfriend, the American actress Blair Brown; and is devoted to his three children, whom he cares for at his house in Notting Hill Gate when they aren’t with their mother Margaret Matheson, a handsome and intelligent television producer. (Hare and Matheson married in 1970 and divorced in 1980 but remain friends.)

Hare was born on June 5, 1947, in Bexhill-on-Sea. Here, he lived with his mother in a modest semidetached while his father, a ship’s purser, was away at sea. From this socially inauspicious background, he was removed to Lancing College, a public school that despised Hare’s accent and class and forced him to take on protective coloring. He thereafter condemned himself for joining such an ugly system. He went on to read English at Cambridge University. In 1968 he confounded the Portable Theatre, working with Howard Brenton and Snoo Wilson. He succeeded his friend Christopher Hampton as literary manager of the Royal Court. He then worked with William Gaskill and the Joint Stock Theatre Group. He has also worked at the National Theatre and at Joseph Papp’s Public Theatre.

Hare’s friend Stephen Frears points out that nowadays he and his fellow dissidents of the ’60s and ’70s are “defending cricket and civilization—all the things we were attacking before Thatcher.” Hare is also pointing to how things ought to be. Beyond and above that, his province is deep and demandingly mysterious.

KATHLEEN TYNAN: You fell into playwriting, didn’t you?

DAVID HARE: I fell into writing plays by accident. But the reason I write plays is that it’s the only thing I’m any good at. It was a long time before I discovered I had a gift for anything.

TYNAN: You were very good at directing, Michael Blakemore says that you have “the capacity to make the moments count so that there’s an unbroken line of energy.”

HARE: Insofar as I’m good at directing, it’s because I’ve now become a writer. I started writing because we had to fill a slot in the program that somebody else failed to fill. Then, when I discovered that I had a gift for writing dialogue, I just cheered up to no end as a person because I wasn’t useless. Actors taught me to direct, but that came much later. It was Trevor’s (Griffiths) play, actually. I was doing The Party with Fulton Mackay and Jack Shepherd. They made me see things the actor’s way, and then I became a much better director.

TYNAN: One of the most impressive things about your plays is that the pacing and the music are wonderful. But you never attach dialogue to a character very recognizably, do you?

HARE: No.

TYNAN: Is that by choice?

HARE: When Kate (Nelligan) first read Knuckle, she asked, “Why do all the characters talk the same?” I said, “Well, they feel completely different things, and they do express this in different ways, but the fact is there is a such thing as style.” It’s like being a painter. You paint in a certain style. I would regard as a very bad painting one in which each figure was drawn in a different style. I went to see a Lucian Freud exhibition, which influenced me very, very profoundly because I began to understand portraiture. He made me recognized what I’d known all along and had never been able to articulate, which is that portraiture isn’t everything to do with likeness. It’s to do with emotional affinity.

TYNAN: Richard (Eyre, the new director of the National Theatre) says—and I feel the same way—that your plays get better and better. This suggests a long career. I mean, there are certain playwrights who producer four or five or even a dozen plays, and that’s it.

HARE: My own view is that they’re getting better. I think the difficulty is that I had a gift and a facility, and it took me a very long time to understand my own emotions. I remember Max (Stafford Clark, of the Royal Court) saying something, which has absolutely haunted me, He said, “The problem with you, David, is that you want to be entertaining every moment.” What he was effectively saying is that my gift is very flashy. It’s taken me a long time to express myself rather than let my gift run me.

TYNAN: Why are you accused—and I say this with some surprise—of being a cold writer?

HARE:I don’t know. It absolutely mystifies me. I’m absolutely bemused by it. I mean, it’s just a fact that almost all the greatest performances of my work have been given by foreigners. Kate Nelligan is Canadian, Blair Brown is American; so are Meryl Streep and Irene Worth. I’m often writing about the difficulty the English have with feelings, but the feeling has to be burning away underneath. And English actors do slightly drain my work of feeling. Foreign actors understand that it’s very, very emotional. So does the American audience. Also, my work’s described as cold because it’s about moral things, and anybody who writes about moral things, about what you should do, or whether there’s such a word as “ought,” is accused of being cold.

TYNAN: Or rectitudinous. You’re immediately put on the side of the Roundheads rather than that of the Cavaliers.

HARE: Exactly. But the plays and films are obviously getting so much more romantic.

TYNAN: Your agent, Peggy Ramsay, said that there’s not too much “throb” in David, by which she meant not that you aren’t emotional, but that you don’t spill all over the place.

HARE: I don’t think of my plays as steamy places where people display huge amounts of emotions. The feeling is underneath, which in my experience is where most feeling is. I don’t myself spend my life shouting in rooms, and I don’t really believe things in which people do spend their time in total hysteria. Bill Gaskill, who was running the Royal Court, once said to me: “Hysteria is actually the easiest emotion to get going. You can get it going on a bus, you can get it going in the theatre.” And it’s true.

TYNAN: Politics. Let’s come back to feeling later. Are you an Orwell admirer?

HARE: I like Orwell’s writing very much but he was an essayist dabbling in fiction. I don’t think his fiction is densely imagined.

TYNAN: But from a political point of view?

HARE: You mean, do I like his politics? Yes. I do like his politics and plainly my politics are not a mile away from his. Trying to be a socialist and a libertarian is obviously a very difficult balancing act, which nobody has pulled off too successfully in this century. But Orwell is one of the people who has come closest to pulling it off. I don’t agree with his suspicion of the organized left. He’s sort of a non-joiner. But he doesn’t seem to understand that that’s just something writers temperamentally are. They’re not very good at joining things. There was a meeting the other night to attempt to get novelists and playwrights into some sort of broad movement of the left.

TYNAN: Who was organizing it?

HARE: Harold Pinter. You could tell they were all going to fall out before they came into the room. You can dragoon right-wing journalists, who will simply say what they’re told to by Thatcher or by representatives of Thatcher. But getting left-wing people to agree with anything is very, very hard. They don’t like lying on behalf of a cause. Whereas right-wing journalists will say anything. One of the depressing things in England at the moment is the total orthodoxy: the law is handed down from Downing Street.

TYNAN: But you said somewhere that Thatcher absolves us from worrying about other people’s lives. You do have to go to Harold’s meetings or whatever it might be.

HARE: Yes, you do. But what politicians want and what creative writers want will always be profoundly different, because I’m afraid all politicians, of whatever hue, want propaganda, and writers want the truth, and they’re not compatible. For a politician, the mans to power is paramount, and the ideology, in a way, can look after itself; I’m afraid a writer can’t think like that. A writer has to think that it’s more important to be right than to be popular.

TYNAN: So, other than writing about these things in your own work, is there any way in your private life that you can be a socialist?

HARE: I’m vey bad at marshaling arguments. I can’t, at a dinner party, explain why I’m a socialist and why others should be socialists as well. I’m not good at standing on platforms and persuading people to my political point of view. Nor would I seek to. My gift is completely different. It’s for presenting an imaginative version of the world which I hope people would recognize and be affected by. Finally Lenin and Gorky will always fall out. If they don’t understand that, they can’t help each other. If they do understand hat, they can help each other.

TYNAN: What policies do you support?

HARE: If you do the things that Britain needs to do—namely, withdraw from NATO, get rid of the bomb, and stop being aligned with one side of the Cold War—then presumably the run on the pound, the result in the stock exchanges of the world, will be fairly catastrophic for the economy. But some sort of political realignment is plainly what this country needs. I’ve absolutely no doubt that the state ought to do a great deal more than it does to help the lowest, the worst-off members.

TYNAN: What do you have to say about Thatcher?

HARE: She’s got the smallest percentage of the electorate of any prime minister since the war. She’s the least popular prime minister and actually, the people who dislike her actively make up the highest number since the war. But the facts simply don’t appear in the official version, and she’s universally admired by the press. She has television cowed, so her control of the media is very powerful

But, when a statistic appears—as it did in the Sunday Times last week—saying that 48 percent of the electorate would like the country to be more socialist in its outlook, this statistic is simply glossed over. It’s suppressed. It will never appear again. And the official propaganda version keeps being pumped out from television stations and the press. They simply lie about her popularity. It’s disorienting to foreigners, who can’t understand it.

TYNAN: It’s very effective because the word “radical” is attached to it.

HARE: I don’t see anything radical about her at all.

TYNAN: Not even the smashing of the welfare state?

HARE: This whole thing of the Thatcher revolution—I don’t feel that she’s truly transformed the country in any direction different from the direction that Edward Heath would have liked to take it in. What she wants to do is what all the Tories have always wanted to do, namely, take away from the poor and give to the rich. That’s what she’s done.

TYNAN: Bye-bye, Mrs. Thatcher. Oh, no, stay here, Mrs. Thatcher. Your new play was originally called The Power of Prayer?

HARE: Now it’s called The Secret Rapture—the moment when the nuns meet Christ.

TYNAN: Apart from that, it is about Thatcherism. Did you intend it to be?

HARE: Yes, I mean, it’s very hard to write about now, and there’s obviously been an absence of plays about the ’80s. You know, playwrights have gone quiet about the times they live in.

The two plays about aversion in the ’80s that have made some impression are Pravda (by Hare and Howard Benton) and Caryl Churchill’s Serious Money. Both swim the audience round behind the villain. Lambert Le Reux is celebrated, just as Michael Douglas’ character is the popular character in Wall Street. Ron Silver’s character is the popular character in David Mamet’s Speed-the-Plow. Serious Money is basically a celebration of malign energy. Speed-the-Plow, Pravda, and Serious Money all celebrate malign energy. They all say, this is the force and the force is sweeping through the decade and nothing can stop it unless you bastards organize. In Speed-the-Plow the opposition to Ron Silver is feeble and deeply unconvincing. The other two parts are psychologically unplayable. Mamet’s the writer I admire most but he’s way off from when he tries to talk about what the moral appeal of liberal thought is. His heart is not in it.

And they don’t give the Tony Award to the actor who has to play the poor liberal. They give the Tony Award to Ron Silver, because he’s playing the character who is what America wants to be. It’s the same with Wall Street; they give the Oscar to Michael Douglas. They’re not giving it to the actor; they’re giving it to the character.

Glengarry Glen Ross, to me, is the only play about the ’80s that really gets anywhere, because it’s about fear. It’s about terror—people living their lives in sheer terror. That’s why it’s a great play. The Secret Rapture tries not to use the device of malign energy to write about the ’80s. It’s about people who are corrupted by the age. Because of that, they take certain attitudes to be the good character.

TYNAN: But the good character prevails; her capacity for love affects the others.

HARE: Yes, but she gets driven back. The director in London remarked to me that the times are so one-way now that when you hear things you stop in absolute disbelief and you think, “How do I begin to explain to this person that my point of view is completely opposite to the orthodoxy?” The orthodoxy of America is as rigid as that of Soviet Russia. There is one point of view allowed. If you start a conversation from another point of view, the words dry in your mouth. Isobel is a woman who has certain values, but, I’m afraid, in the course of the evening she becomes less and less able to articulate them because of the effort of trying to swing around people who are so rigid in their way of thinking. That’s really what the play is about. The play is a tragedy and she has a fatal flaw. What is her fatal flaw? That she’s a good person. People gang up on her because implicitly they feel criticized by her. That, I’m afraid, is the effect of good nowadays.

TYNAN: How do you change things?

HARE: I don’t think one changes things. Things change.

TYNAN: With small acts that add up: refusing to go somewhere, or writing a play that’s a fictionalized version of a newspaper baron’s behavior in England.

HARE: What happened with Pravda—which was terribly interesting—was that people began laughing even before the play had begun. The first character came out onto the stage and was met with a gale of laughter. The fact that the audience knew in advance that they wanted the play. They were going to approve of it, however incompetent or competent it was, because it caught something in the time and it was in the air that if there was a good antiestablishment or antipress play, that is what people craved at the moment. The sensation was like sailing downwind for the first time in my life. The audience blew the boat downwind. You couldn’t go wrong.

TYNAN:Is this a play that could “go” in New York?

HARE: I don’t know. It’s never made it to New York because it’s been so elaborate. There are 30 characters. It’s pure luck when you hit it like that, but everybody knows that moment in the theatre. It obviously happened on a much larger scale with Look Back in Anger, hitting this deep sociological lode. When you’ve hit it, it’s the most extraordinary sensation. It’s only happened to me once, but you think: I’ve got it absolutely right. There it is—what people want. I didn’t even know they wanted it before they came in, but there it is. It’s very exciting.

TYNAN: You clearly want to break through and get a strong audience reaction. But perhaps sometimes your standards are too high. There seems to be some sort of dialogue in your work—not necessarily a friendly one—between you and you.

HARE: Yes. In The Bay at Nice and Wrecked Eggs I had to sort out various things. I cared very little about whether the public came to see these plays. We deliberately presented them in a small theater. We put them on because I couldn’t grow up unless I worked out some things I felt.

TYNAN: You might like to describe what these plays are.

HARE: The Bay at Nice is a play, set in the ’50s in Leningrad, about the authentication of a Matisse by a woman who has lived in Russia all her life. The characters, played very brilliantly by Irene Worth, has to decide whether this Matisse is authentic or not. It’s set against the background of her daughter’s divorce. In the second play life in Russia is contrasted with life in America, where people, although theoretically free, lead lives as rigid as the lives in Russia. It’s an East-West evening.

TYNAN: It’s a satire on American self-absorption.

HARE: Yes. The American half of the evening is not as strong as the Russian, so I’ve been nervous about presenting the plays in New York. I wrote them for Blair Brown, who’s not been free to play them except at a time when Joe Papp had no theater present in the. Bad luck. But perhaps it’s for the best.

TYNAN: Is this the only time you’ve written for a particular actor?

HARE: Yes.

TYNAN: Was she your model?

HARE: Not really. It’s more complicated than Picasso’s model was so-and-so and yet you can’t find a single thing that remotely resembles her. It’s profound.

TYNAN: It’s wonderful if it produces a profound result, not if you’re simply trying to disguise your sources.

HARE: Absolutely.

TYNAN: Do you keep a notebook? Do you write down raw material?

HARE: Oh, yes. But not raw material. I don’t do what Alan Bennett does, which is to sit on a bus and copy down a remark. I am much more of a portraitist in the sense that anything that fits the sort of world I belong in.

TYNAN: But surely there is a lot of power in taking the brutality and effectiveness of, say, a dream or somebody’s behavior and simply putting it down on the page. Once you start playing around with it, it loses its potency, its content.

HARE: No. This whole idea that you can just slap down your life and it will turn out to be art is a load of nonsense. If there’s, say, a couple of minutes of your life that you can actually transcribe, then you will have to work for an hour onstage to create the fiction that gets you to that two minutes, and then you’ll have to work for the next hour to get away from it.

TYNAN: I suspect that in year to come one of the criticisms in your work will be that it took some time to hit the mark. Rather like Lucian Freud’s paintings.

HARE: I can’t worry about it. I think a work and its reception are two completely different things. I don’t worry anymore about the effects. Peggy (Ramsay) said to me when I started out: “The more you’re attacked, the more successful your work will become. Just never pause to think about an individual comment or review, or your reputation, because you’re the kind of writer who, every time you write, will be attacked and yet the more you write the more effect the plays will have.” When she took me on—because of Knuckle—she said, “This is an incredibly important play.” I said, “Oh, you mean it will be very successful?” She said: “Good Lord, no. Everybody’s going to hate it. But that doesn’t mean it isn’t an important play.” She always understood that the two have nothing to do with each other. She said, “You’re on a 20-year burn.”

I learned this again with the musical The Knife, which we presented in New York in 1987. Nick Bicât is the only composer now working to take the form of the musical and do something incredibly radical and exciting with it and still produce something beautiful. Who noticed? Well, just the odd crazy who comes up to me in the street and tells me it was the best night of their theatre-going life. No one else, God knows.

TYNAN: Do you have a good relationship with your audience?

HARE: I have a very, very good relationship with 10 percent of the audience. The only purpose of art is intimacy. That’s the only point.

TYNAN: And to be liked by people you care about. However, that’s not what theater is about. I think the theater has to engender reciprocity between the two elements: the stage and the audience.

HARE: The majority don’t like me before the curtain goes up, and I always have to win them. Pravda was the only exception. They’ve always been against me before I start, and then I either pull them round or I fail to pull them round. To the small wedge in the brie I’m speaking more intimately than anybody. I’m the voice they really want to listen to. The rest of them have no clue at all about what’s going on. My film Wetherby was where I changed about this, because I delivered something I didn’t fully understand. I just knew that there would be a certain section of the audience for whom these images had a very profound resonance. It’s something I’ve been frightened of in the past. I never used to kill characters, because I thought killing characters was cheating.

TYNAN: Pornographic.

HARE: It’s using an easy emotion. Of course, if you kill a character people feel sad. That’s too easy. Now I’m not frightened of those things. In the film Strapless, one of the characters is going to give birth. Five years ago, I would never have dared to do these things because I felt instinctively that it’s cheating to use devices that are so powerful.

TYNAN: You don’t earn it.

HARE: Exactly. Whereas now I feel that the emotion is actually going to be justified.

TYNAN: Strapless is the film with Blair Brown?

HARE: Yes, it’s about romantic love. Blair plays a doctor in a cancer hospital in London who loves and loses a man, played by Bruno Ganz, who can’t deal with ordinary life at all. So he leaves. He loves this woman from the bottom of his heart. But what’s the point of love? The point of love is the overturning.

TYNAN: The overturning?

HARE: Yes, the overturning of everything, of all your feelings. The rest is the bit where you actually have to go on living.

TYNAN: It’s not merely sexual, this mysterious addiction.

HARE: I’m trying to write something in which you know that it’s all about sex but you never see any. Well it’s not all about sex, but sex is surely the thing that carries the spiritual charge, isn’t it? You see, the reason I’ve had great difficulty with the screenplay is that it was basically about a woman who opens the box and then finds these feelings coming out. Then, because the man disappears, the puts the lid back on the box and says: “Well, that’s romantic love. It’s everything, but it’s nothing. It’s totally sublime, but it also has no relationship with the rest of your life.”

It’s taken months to work out that I don’t believe that. I actually think love changes everything. I think it’s the only thing worth having. And also, what I’ve been fighting to get right is the sense that you’re changed by it. Now, to show that in a film is fantastically difficult—to show that you are changed by it, and so are your relationships with other people. I want her to come out of it better off, in spite of the fact that the man has vanished.

TYNAN: Are you changed? You’re not necessarily more generous or more socially useful.

HARE: I think you are.

TYNAN: I mean, this woman has lost the man she is in love with. How does that alter her behavior?

HARE: I believe love opens people up. Picking up the bill, after all, is part of feeling. If you feel, then you’ve got to pick up the bill. That’s what we come to understand.

TYNAN: You said you couldn’t act because acting involved access to your feelings.

HARE: No, I can’t imagine manufacturing emotions in public. One of the things I find about getting older is that I seem to get louder, more voluble; that I constantly have to walk around repressing my vitality. It’s one of the things about England. Everyone’s so muted that I feel like a big man in China.

TYNAN: What do you feel like in the States?

HARE: I think I go quite quiet in the States.

TYNAN: Do you like being there?

HARE: I don’t, terribly. I used to get a great charge from it, and I think that’s all it’s good for—for the English. It’s the drug. It’s getting there and getting a burst. I can’t imagine writing there. I can’t imaging living there because of the usual English writer’s problem, which is that there is the illusion of England that people are listening and that you have some effect. It’s an essential illusion—that the society is still amenable to being talked to.

TYNAN: You were listened to when your plays were on in New York.

HARE: I never knew what the consequences were.

TYNAN: You could see success, but you didn’t hear a dialogue. Didn’t you feel an intimacy?

HARE: I think the novel is the American form because people read it in private, and the only valuable things that happen in America happen in private life, because public life is a dead loss. They may as well go to some idiot musical, because when they get together to think about ideas or feelings, there’s no way in which they can use what they come out of the theatre with to change the essential facts of their own lives. In England there is a sense that you’re part of a broad continuity of liberal writing and that there are still parts of the society that can be affected by the way you think and by the theatre’s being sued as a way of addressing the country. Which is undoubtedly was with Pravda. The Prime Minister knew perfectly well that at the National Theatre, there was a play which was a rallying point for opposition to the government. It may have caused her three seconds’ pause, but it got there in some way that in America is impossible.

TYNAN: So you think you make a difference by working inside the establishment?

HARE: I don’t see the theater as an establishment. The National Theatre has always seemed to me a people’s theater. It was never meant to reinforce the values of the government of the day, nor does it, nor should it. On the contrary, it’s the place from which the Government has been attacked, and quite rightly. The theatre isn’t part of the establishment. It never can be unless it’s dead theatre.

TYNAN: Your new film, Paris by Night—what’s it about?

HARE: It’s about a member of the European Parliament, and I can’t quite remember now what it’s about. It’s about the old things, what all my work is about. It’s about the soul.

TYNAN: Does the character lose her soul? Does she have a soul?

HARE: Yes. It’s exactly about that. Are we just what comes out of our mouths? Or are we more than that? It’s about a woman who seems to be nothing except what is ever passing through her mind. To me, the most frightening idea is that we are only the stuff that’s going on—the inner dialogue and the words. So I try to give the audience the fright of their lives by saying to them, “Now do you think this is all life is?” Paris by Night really is a thriller. It’s about death. It occurred to me that the thriller was a really profound form. I realized it because it plays with the idea of when you will die. It’s inevitable that you will die, so the only question is when. The great thrillers are the moments that play and tease with the question, “When will it be?” In a way the form itself is as profound as tragedy. I’ve tried to write a tragedy in The Secret Rapture, because when you get to the age I’m at, then you feel death not at the end of the road, but death all around you, in everything. Life is saturated with death. I feel death everywhere.

So it’s not at the end. It’s all around us. And tragedy is the form that recognizes whichever the protagonist is—is going to die, and it’s as inevitable as it can be from the moment you see her. The play would be a failure for me unless the sense that she must die is there as a drumbeat throughout.

TYNAN: You know, some people have trouble with Plenty—however much they love it—in that they feel these exceptions are set up which were meant to have some resolution and they’re not given any.

HARE: Right. I regret that. One of the things about Isobel (in The Secret Rapture) that’s very hard to get right is that she withdraws, and yet I was very keen that she shouldn’t be mad. As soon as the Audience hears that word, they cop out: “Oh she’s mad.” The second act of Plenty was extensively rewritten after I discussed it with Kate (Nelligan), whose own mother went mad. Kate had this tremendous anger with her mother about the ease of being mad, that madness was the great get-out. Once you behave madly, then it’s emotionally such an easy thing to be. It’s a cop-out.

The same thing is in the character Katherine in The Secret Rapture. Here is somebody who wants to have it proved to her all the time that she’s incompetent, that she’s a failure. She is constantly on the search for evidence that she’s no good. As soon as she finds that evidence, she says, “There. I told you I was no good.”

Well, it’s very easy to live your life like that. Finally, this is where I am cold. It is a cycle that people get into—a cycle of self-pity—and it can be broken only cruelly, I’m afraid. So The Secret Rapture is quite a harsh play in saying that compassion isn’t necessarily the best way to treat people who are in the self-feeding syndrome.

TYNAN: When you are deprived of romantic love, when that’s no longer there, is there anywhere else to look for nourishment?

HARE: Well, plainly in one’s children and in the exercise of work. I’m lucky enough to do work that is profoundly satisfying. Whether I’d feel that if I were working behind the perfume counter at Selfridges, I rather doubt.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY RAN IN THE APRIL 1989 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

New Again runs every Wednesday. For more, click here.