David Gordon’s First Draft

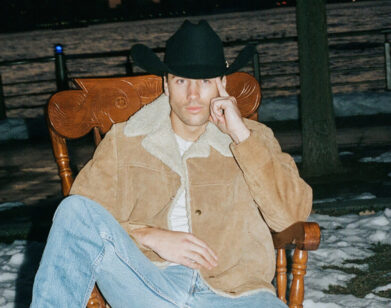

ABOVE: DAVID GORDON. PHOTO COURTESY OF MICHAEL SHARKEY.

David Gordon’s Mystery Girl is not an easy novel to follow. Of the many characters, there are perhaps three or four whose identities and names don’t change at least twice. Inspired by the classic noir or the ’40s and ’50s, it is a madcap, high-energy investigation into the shadowy and perverse world of avant-garde, pornographic filmmaking in modern-day Los Angeles. Even as the book travels up the coast to Big Sur or down south into Mexico, Gordon’s elaborate and exact attention to small detail and sometimes outlandish humor holds the attention rapt. This book has the quality—in the best possible way—of your friend bumping into you in a coffee shop, slumping into the seat opposite yours and, before you have a chance to say a word, telling you that you have no idea what his weekend was like. You’re not sure what’s coming next, but you know you’re in for a heck of a ride. We sat down with Gordon to discuss plot twists, pornography, and the therapeutic effects of running.

MICHAEL HAFFORD: There are a lot of twists and turns; double and triple identities. Did you have an ending or story arc in mind when you started?

DAVID GORDON: A little of both. I knew the ending. Literally, these two people were going to be in this situation in the middle of the desert. I even had some sense of the lines. I don’t want to say who, but he and she. The very end, the last moment. That last image of a couple in the desert facing each other and saying these lines of dialogue. That idea of the couple alone, together in the desert. I had that. But I didn’t know how they got there or why they were saying these things to each other, even though I had the dialogue. Working out the various twists and turns was unbelievably difficult and painful. I had charts and cards [but] even then, there was a point maybe 60 or 70 pages into the first draft where I realized I had everything figured out wrong and I had to scrap everything and go back. I actually—maybe my mind was playing tricks on me—but I literally went to the mirror one day and there was a new line in my forehead that I now name Mystery Girl. [laughs] So, yes, I feel that I sprained something in my head trying to figure this all out.

HAFFORD: Pornography pops up a lot in the book, in terms of all the movies that Zed Naught produces. Is that something you think about as a writer; the pornographic aspect of watching these people perform and the extreme emotions that they’re feeling?

GORDON: Yeah, I think that’s a good way to put it. Obviously, sex and desire and romantic love are part of the engine of this book. I felt like it was important to have that material in there. I also feel like it’s also an area that—how should I put it?—we can’t not look at a picture of a naked person, no matter how badly done. A lot of the photos that I would actually be publishing in these magazines [in my time working for Hustler and associated publications] were so poorly composed. I’d be so happy when someone came along who was just a good photographer—who didn’t have the model smile in every single picture. Just things like that. And yet, you have to look. Whether you’re talking about advertising or you’re talking about Lucian Freud, there’s something about that realm that compels attention and, the other thing you brought up which I think is interesting, it compels strong and extreme emotions. I think that’s really the thing because I’m basically sitting by myself and endlessly writing all day. Whether I’m writing about sex or I’m writing about the stock market, neither one is all that salacious. [laughs] You’re basically endlessly rewriting the same sentence. If I can get into territory that brings up strong emotions in readers and characters, I think it brings them to life and it gets interesting. I think that matters more to me than whether anyone thinks it’s sexy, or whatever.

HAFFORD: How many drafts of your work do you do before you send it to an agent?

GORDON: A lot. I do many drafts of almost everything. The only thing I don’t do multiple drafts of is texts and quick emails, and when I go back and look at them, I’ve made a ridiculous number of mistakes and sent them to the wrong person, so even then I should probably be doing three to five drafts. I’m going to say 10, give or take, and then a few more with my editor. I would say 12 to 14 drafts is a good rule of thumb for something to get from a vague idea in my head to published work out in the world. The truth is, even then, if I let myself read too many pages I instinctively want to reach for that invisible pencil in my pocket and start changing things, even if it’s in a magazine and I can’t do anything about it. I try my best to not stop too much during a draft—I try not to look in the rearview mirror more than I have to. Inevitably I do have to. Inevitably I crash, and I have to restructure everything. If I have momentum I try to keep going because I’m so afraid if I reread it, I’ll have to go back to the first word and change everything. It’s kind of like that cartoon character who runs off the cliff who doesn’t fall until he looks down. I try not to look down until I absolutely have to. And then I do and it’s like “Oh my god, it’s a disaster.” And that’s draft two. [laughs].

HAFFORD: Someone told me the other day that if your character needs to have a different job or have something changed about him, to just do it and worry about going back and fixing it later.

GORDON: That’s the miracle of word processing. Think about when every one of those changes meant retyping. I agree. The problem then, though, is that I literally forget and sometimes I have characters whose names change three or four times in the course of the story. Remember, too, that there’s a time factor. If you’re drafting novels, you maybe haven’t gone back and looked at chapter two in months. So, suddenly you’re re-reading this thing and you’re like, “Mary, Marcy, Marlene, Magdalene,” and you’re like, “Wait a second.” Another thing I do is write notes to myself and tape them to the wall right in front of my face. I actually have some pictures somewhere of the Mystery Girl wall, because I was moving. Basically the whole wall of my room is this weird collage art project of scraps of paper and charts of things that bit by bit I kept adding. And theoretically I would go back and change those things. That’s another thing you can do, is somehow remind yourself. Whether it’s a Post-it or notes in the margin or, in my case, ripping out a page of my notebook and putting it on the wall that says, “Make him taller.” [laughs]

HAFFORD: People would think it’s a serial killer’s apartment or something.

GORDON: Very much so, yeah. I’ve always had weird encounters with neighbors or roommates or significant others. You’re always the weirdo. Neighbors were constantly asking me… they basically thought I was a bum, because I would be walking to the deli at like four in the afternoon and they would ask me if I had just woken up, or I was sick. I would be in pajama pants with crazy hair and talking to myself. I’ve had people tell me that they’ve spotted me on the street mumbling to myself and laughing. I said, “Oh, I was probably on the phone.” And they said, “No, your hands were in your pockets. You were just standing on the corner, laughing, and your lips were moving.” So stuff like that. You definitely become kind of an oddball.

HAFFORD: That’s when it’s going great, though; it’s when you’re not talking that it’s a problem.

GORDON: It depends on what you’re saying to yourself. If what you’re saying is, “You suck, you suck, you suck,” then it’s time to go running. That’s the other thing that I think saves novelists from going mad is I recommend running.

MYSTERY GIRL IS ON SALE NOW. DAVID GORDON WILL TALK TONIGHT, AUGUST 1, WITH RIVKA GALCHEN AT POWERHOUSE ARENA IN BROOKLYN. FOR MORE ON GORDON, VISIT HIS BLOG.