Adam Langer is Not In Hiding

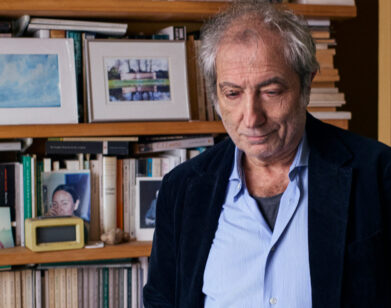

ABOVE: ADAM LANGER

The Adam Langer we met for lunch in Soho last week isn’t the same person as the Adam Langer who is the protagonist of Langer’s latest novel, The Salinger Contract. Not exactly, anyway, though at the time of writing the novel he did have certain things in common with his character: a quiet, involuntarily semi-reclusive life in Bloomington, Indiana, with a German-born academic wife; a CV that includes both creative writing and an editorial tenure at a since-folded literary magazine; a deep familiarity with, and rightful suspicion of, the publishing world.

The last of these is perhaps the most useful in explaining what happens to the fictional Adam Langer—and what made the real Adam Langer want to write it. His complex story is comprised of puzzles within puzzles, and to reveal too much about would be a disservice to its tight construction, so a brief description will suffice. In the novel, onetime novelist and current househusband Langer runs into an old friendly acquaintance, Conner Joyce, a crime novelist whose work, once bestselling and prized for its specificity, has been made obsolete by the popularity of crime shows on TV. Joyce begins to tell Langer the story of how he’s been contacted by Dex, a mysterious benefactor who promises an unheard-of sum in exchange for a novel Joyce will write for Dex’s eyes only. Of course, it can’t be quite that simple, and as the story twists forward at a satisfying clip, it comes to implicate a variety of reclusive authors—Salinger, Pynchon, Harper Lee—and, eventually, Langer himself. (The fictional one, that is… we think.)

ALEXANDRIA SYMONDS: How much do you read in a week?

ADAM LANGER: This week? Nothing. [laughs] It depends. I just had to review three 500-page books in a row, so I’m taking a break. How much do you read in a week?

SYMONDS: I guess that depends, too. I’d never read Infinite Jest, so I’ve been…

LANGER: It’s on my phone. It’s the first download I did.

SYMONDS: I can’t imagine how long it takes to scroll through.

LANGER: It’s completely demoralizing, because you read like what you think is a lot of pages and you don’t clear one percent.

SYMONDS: Yeah, I’ve been reading on an iPad too. But I’ve been taking a lot of breaks—every hundred pages or so, I’ll take a break and read something else, because I feel like that’s the only way to maintain your sanity through all that tennis.

LANGER: I have to say, I did that, and I’m now in the midst of what I would call a four-month break.

SYMONDS: I want to ask you about the kind of narrative of frustrated talent, or frustrated expectation. The heady period of potential is really romanticized in literary culture.

LANGER: Then you actually have to have a life and a career afterwards.

SYMONDS: Right, which is not addressed as much. What kinds of conversations have you had with friends in publishing about that topic?

LANGER: I don’t have that many friends in publishing.

SYMONDS: That’s probably even better.

LANGER: That’s kind of disingenuous. I think even among friends, it’s hard to have a friend close enough that you can tell what’s actually happening. Everyone, particularly in the Facebook/Twitter universe, you’re always kind of promoting yourself. You’re always kind of putting forth the best version of what’s happening and kind of deleting all the other parts of your character that might be having self-doubt or might be having struggles. Whenever you talk to other writers, or at least when I do, everything is always going great. So, then there’s this pressure on you that it has to be going that way with you, too.

SYMONDS: It becomes an ouroboros—nobody talks about it because nobody talks about it.

LANGER: This is going to sound really obnoxious in a way, but there was this time in 2004, ‘5, ‘6 when everyone was getting “six-figure deals” for books, and we’d all sit around and talk about that. But Joe Shmoe, who got, I don’t know, $150,000 for his book and wrote his book over the course of five years, split that with his agent—he’s really, if you quantify it, making as much as some entry-level administrative assistant. It’s not that grim, but that’s the kind of stuff you don’t talk about. You spend a lot of time talking about whatever the literary equivalent of “first-world problems” is.

SYMONDS: [laughs] I think they’re still just first-world problems.

LANGER: Like, “Oh yeah, my agent didn’t like this one.” Or “I didn’t sell the UK rights,” or something. Nice problems to have. But when you’re trying to have a career and a family and everything, they are problems.

SYMONDS: No, that’s genuine, for sure. But specifically, that weird moment after the first book, is that something you feel like you’ve talked to a lot of people about?

LANGER: Not really—because, by the time the first book is coming out, your second’s almost done. There’s not time to reflect on, “Well, that was the first book, and here’s the second, and it’s going to do this.” You get on this—it’s not a rollercoaster, because it’s not that interesting, but pick your metaphor. It’s some sort of a journey. Because the first book is all potential and you’re just happy to have your name on a book and have it in a bookstore and have someone review it, and then it comes with all the expectations the second time of what that book didn’t do and what the next one’s going to do, and it doesn’t always do all that.

SYMONDS: I’m hesitant to talk too much about Salinger, because I don’t want to give anything away.

LANGER: So let’s talk about Salinger, but not too much. Have you seen the movie, by the way?

SYMONDS: I haven’t. I was going to ask you whether you’ve seen the movie or gotten an advance copy of the book. When you found out that all this stuff was coming out right around the same time as your book is, were you excited to be included in this trend or upset by it?

LANGER: Neither. I think from a marketing standpoint it’s convenient, but I was never a big Salinger guy and part of my book is almost satirizing the person who’s so into that. I mean, anything that makes you part of a conversation is fine, but if roundups are looking for people to talk about the magic of reading J.D. Salinger, I’m kind of the wrong messenger for that. Yeah, I don’t know, someone sent me a copy of the book, I saw the movie…

SYMONDS: What did you think?

LANGER: It sucked.

SYMONDS: That’s exactly what I heard.

LANGER: Part of it can’t help but be interesting, because it is sort of an interesting story and he is an interesting, even if sort of an unappealing character. And it does talk to a lot of people who you haven’t seen on screen before and takes you into a whole literary world and a time 50, 60 years ago, when authors were viewed like that. I heard the movie opened very well, but I went to the theater on the second night and there were only 11 other people in the theater. The kind of thing that’s almost more interesting or disturbing to me was not whether these questions about Salinger are answered or not, but whether it even matters to anybody.

SYMONDS: The premise of your novel in the first place…

LANGER: Define what that premise is. I have trouble talking about it.

SYMONDS: It’s the story, told through a frame narrative, of a sort of down-on-his-luck former best-selling author who gets the opportunity of a lifetime from a shadowy patron figure who wants to finance a new book.

LANGER: That’s good.

SYMONDS: Thanks. [laughs] That’s very nerve-wracking to do, to describe something to the person who created it.

LANGER: Oh no, it’s even more nerve-wracking for the person who wrote it.

SYMONDS: I believe that, yeah.

LANGER: Someone’s like, “What’s the book about,” and you’re like, “I don’t know, some stuff.”

SYMONDS: Well, I think that if writers were especially good at elevator pitches, they’d be in advertising.

LANGER: No, it’s true. But you’re kind of drilled to be good at it.

SYMONDS: It’s an auxiliary skill that you don’t want to have to have. [laughs] So anyway, I don’t want to ask where that came from, but I do want to ask where that came from…

LANGER: I kind of had a feeling you were going to ask that; and every time I talk to somebody, they say, “Where did the idea come from,” and each time I remember something different. The answer is always true, but it’s always different. So I just remembered something today, which is I was out in Los Angeles talking to a TV producer who was trying to give me ideas of things to write, and he said, “I really want a modern Murder, She Wrote,” which I thought was like the worst idea I’d ever heard.

SYMONDS: [laughs] Yeah.

LANGER: It’s such a cliché to have the writer who writes about crime turn around and solve them. I thought that was a lame idea, and I didn’t write anything for him, but it did occur to me to completely reverse the polarity on it and come up with an idea of a writer whose books become the basis for crimes. So I think it was almost a knee-jerk reaction to the idea, going out and trying to figure out an idea that would be the absolute opposite.

I think it also came from, authors are getting really good at these self-aggrandizing descriptions of how they write characters and how they write stories. You talk about how books changed your life, and I kind of wanted to play with the idea of taking that very literally. Those two things, and though I was never that into Salinger’s work, I was always kind of interested by this concept of what would lead a writer to disappear, why would they do that.

SYMONDS: It’s always inherently dramatic to explore why things that seem too good to be true are. I wanted to ask about your view of the morality of the contract Conner makes with Dex. I think a lot of people would say that the idea of having a locked cabinet full of possible masterpieces by prized artists is inherently immoral and art should be disseminated as widely as possible.

LANGER: Certainly the person who’s doing that is not a moral, ethical or admirable character.

SYMONDS: No, not at all. But I think there’s an argument to be made that he’s a patron, he commissioned this work, and he’s free to do whatever he wants with it.

LANGER: I think what I was commenting on is—I don’t really buy it, but what is perceived as dwindling readership, disappearance of literary culture, is that at a certain point you might not have a choice and it will be a privilege to be read by one person. Fine art is much different than books because people don’t write books with the idea of just being patronized by one single individual.

SYMONDS: I don’t think people necessarily make art that way either, anymore.

LANGER: Though actually, now that I’m thinking of it, the one thing that was offered to me on a number of occasions, and to other writers I know—because there was this time when writers were getting smaller advances than they had and were trying to figure out how they would make a living; I don’t know if it’s still as prominent as it was—but you would find very, very rich individuals who would want you to write their private autobiography, which was just to be distributed to their family.

SYMONDS: Oh, really, I had no idea about that.

LANGER: I had friends who were fairly prominent in the literary world who would, meet some guy who did not have an apparently interesting life story but who would say, “I will give you double what you normally make for your book. Write my life story.” And if you don’t have a trust fund or residuals, it becomes a very tempting sort of offer. Or there are authors who ghostwrite things, where you may have had a part in something and your name was nowhere to be seen and it’s out in the world —and maybe that’s okay, except your authorship completely disappears from it. Though that’s not what you’re talking about, necessarily.

SYMONDS: No, but it’s an interesting tangent on the same kind of idea, I think. Any time you mix the creative impulse up with economics, you’re getting into thorny territory. But I guess I was asking more broadly whether there’s ever any amount of money that makes it right or that makes it morally acceptable for one person to own a piece of creative work exclusively?

LANGER: To play the devil’s advocate, how is it immoral? Because art should be appreciated by everybody?

SYMONDS: If you believe that the function of art is to reflect and elevate society.

LANGER: But we live in a city where that’s the ideal, but often the art is consumed not necessarily by only one person, but only one sort of person at the same time. And maybe that’s equally morally problematic.

SYMONDS: I guess. That’s more of a collective morality than an individual one.

LANGER: I come from Chicago, which has a very democratic approach. Artists don’t make great livings, but they’re part of a community, and you come to New York and you become part of something very different.

SYMONDS: How long ago did you leave Chicago?

LANGER: 2000. It’s funny, I left Chicago for New York to do what I thought was a book proposal about the morality of corporate funding of arts. I got a fellowship to do this, and when I was just about to start research, I was told by one of the people in charge, who were very glad to give me this fellowship, “We actually have some people you’re talking about who are funding our organization, so we would prefer you not to write that.”

SYMONDS: Wow.

LANGER: So at that point I was faced with a choice of whether I would buckle under to that pressure or whether I would do something completely different, and I decided to write a novel instead, which I didn’t publish but became the basis for my first published novel. When I was in Chicago, whenever you went to the theater, it was Phillip Morris money or AT&T money—Steppenwolf’s Grapes of Wrath, brought to you by AT&T. The corporations weren’t dictating content, but theater companies weren’t going to do anything to piss their funders off. So I wanted to explore that question and see actually how art was affected by the funding, but I never did. I decided to write novels instead.

THE SALINGER CONTRACT IS OUT NOW.