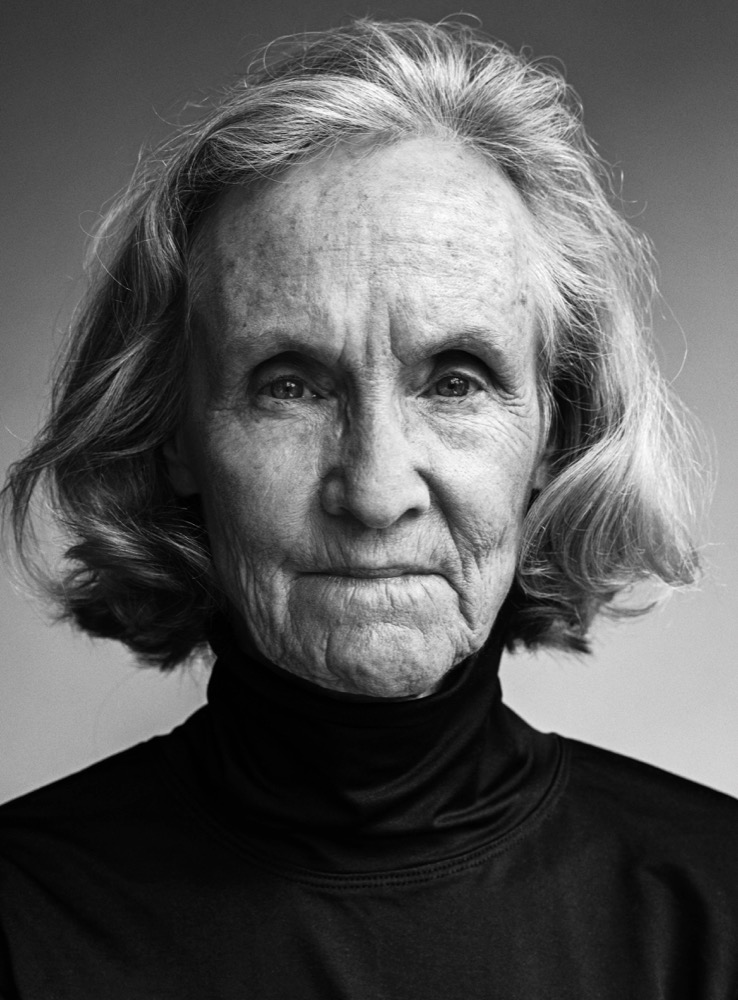

Photographer Tina Barney captures the lives of the upper crust

Tina Barney is an American icon. For 40 years, she has been making photographs that depict the upper crust, rendering the psychological landscape of rarefied social strata with painterly precision. It’s a world familiar to the artist, who grew up in New York among tribes who attend certain schools and summer in certain places; whose houses are called cottages; and whose gestures, habits, and even hairstyles are passed from generation to generation.

Barney’s jarringly intimate yet large-scale images draw the viewer deep into a well-manicured world that encompasses both mundane and stylized expressions of class. The magic of her pictures lies in the tension between the emotional interior of her subjects and her own complex visual compositions, which seem to tear at the highly polished surface—whether it be the East Coast apartments and country homes of her early work; her baronial, blue-blooded The Europeans series (1996-2004); or her most recent project-in-process, Youth, which focuses on teenagers, some of whom are descendants of past subjects. Inside every Barney image is a disarming trust between the photographer and her muse.

This past May, I sat down with Barney in her Manhattan apartment, where we talked about everything from whether or not wealth has changed much in the past four decades—it has not—to the enormous evolution of photography. One of the most telling moments during our time together was unspoken: midway through our conversation, Barney got up to get something, opening a closet that was filled equally with towels, linens, and prints of her photographs—a perfect articulation of her love for the domestic, and proof that the art and the artist are indivisible.

Despite describing herself as a private person, Barney is warm, engaged, and generous about the work of others—no small gift when she’s just finished work on a major monograph covering her many decades of shooting interiors, locations, and the American and European elite, out this month from Rizzoli. And as willing as she is to travel through time and talk about all that she has accomplished, there is a distinct enthusiasm, a twinkle in her blue eyes, which suggests that bubbling beneath the surface is all that she has yet to do.

A.M. HOMES: I think of your work as being very anthropological. It’s beautifully photographic, but also psychological.

TINA BARNEY: Oh, it is. At least I hope it is.

HOMES: How would you describe the evolution of your relationship to the world you chronicle?

BARNEY: In 2015, I started photographing the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of some of the people I had photographed in the past with an 8 × 10 camera—which in itself is a whole different way of taking pictures. It slows you down. It makes you think. It’s much more meditative. I’m at the point now where I don’t really have an agenda. I kind of let things flow, and there’s not a narrative. It’s usually one or two people, and I’m not trying to choreograph them as I did in the past. I’m really just trying to see what’s going on in their minds and in their faces. Shooting these great-grandchildren, who are around the age of 15, is fascinating to me, because they’re right on this fine line between still being children and starting to become themselves.

HOMES: Right. It’s a kind of awareness that’s simultaneously there and not.

BARNEY: The idea of the portrait itself is my great love. The questions and answers in it can go on forever and ever. It is what happens in the eyes or with a tilt of the head. I keep going because it’s too interesting to stop. And with these new subjects, it really seems as if nothing has changed from their parents’ time. The conservatism is extraordinary to me; just compare the way they dress to the way their parents dress. There are still no tattoos or piercings, which is interesting to me. Why does everyone who lives in one place dress alike, look alike, eat the same thing, and decorate the same way?

HOMES: For me, the phenomenon you capture isn’t that different from what Diane Arbus captured in her portraits.

BARNEY: Some of the people she photographed weren’t so far apart from mine in terms of where they came from and lived, and yet it really looked like they were from different planets. Nan Goldin was also interesting to me in the beginning. I don’t know if I ever told her this, but I wanted to switch lives with her for a week.

HOMES: That would have been amazing.

BARNEY: Wouldn’t it? I would not have made it. [Homes laughs] Not physically. I couldn’t have stayed up late enough.

HOMES: You’re polar opposites, in a way, but you both think a lot about color.

BARNEY: Well, color is very important. That comes from style. My mother was a fashion model and an interior decorator, so that was me imitating her. My closest friend’s mother was the same way, and her taste rubbed off on me, too. It’s a domino effect of taste permeating through people.

HOMES: Many of your photographs are also studies of interiors, with echoes of color from one room to another or the patterns of curtains next to a vase. They almost become Dutch paintings.

BARNEY: I started photographing interiors because I didn’t know how to shoot people. I was using a 4 × 5 view camera, and if you’re inside, the exposure has to be long because you need more light. I couldn’t have people sit for that long. When I did start putting people in pictures, I had to have them hold still and I would be yelling out, “One one thousand, two one thousand …” Someone finally introduced me to lighting, and the technical aspect caught up to my dreams about narrative. Those narratives, from early on, had to do with keeping the family together. Then I started to orchestrate these family members being together, getting physically closer, and showing affection. Those pictures from the ’80s are the most well-known. And then I got tired of that, so I shifted to vertical portraiture, which was very much influenced by Thomas Ruff. When I got to Europe in 1996, right away I realized I couldn’t tell these people what to do because they were so formal, so poised and regal. They were fairly intimidating, even the ones I might have known a bit.

HOMES: There is something slightly performative about those European pictures. One has the sense of them kind of coming in and being like, “This is how I will be today,” as opposed to the American families, where it feels more casual.

BARNEY: I’ve always said that the Europeans subconsciously knew how to pose because of the culture or tradition of having your portrait made. They were surrounded by these portraits, and subconsciously they were already posing for them.

HOMES: I’m curious about what happens as you shoot. Do you know when you’ve taken the shot that will be the keeper? In the family portraits, it seems like it’s the moment when things are slightly out of order, when something has happened or is about to happen that throws things off-kilter.

BARNEY: That’s a very good point. In doing this book, I went back and looked at the outtakes. There aren’t any good ones. I usually know when I take the picture. There’s always some kind of un-self-conscious thing going on, so that it doesn’t look like they’re there for the sake of having their portrait taken.

HOMES: You don’t get the sense of people guarding themselves, which you often see in portraiture.

BARNEY: I sometimes get commissioned to photograph families, and they see the results and say, “Oh, I look terrible.” And that’s when I realize the difference between the people I choose and the people who choose me.

HOMES: Do you remember the series that Cindy Sherman did in 2008, in which she portrayed art-collector types? I thought she did it so brilliantly to the point that, even though the characters were fictional, certain people would see themselves in those photographs in awful ways. She captured the essence of certain personalities that felt very authentic.

BARNEY: She sure did. I often think people don’t give Cindy enough credit for being a great actress.

HOMES: I’ve never heard anyone say that, but I think it’s totally true.

BARNEY: From those very first black-and-white images, where she’s standing on the road, she’s so un-self-conscious. I’m just guessing, but I feel like there are elements that most photographers would consider mistakes in both her pictures and in mine, but that we both didn’t tidy up. We keep that sense of something being in the wrong place at the wrong time.

HOMES: That’s what makes them so wonderful. It’s very brave to leave the mess in the frame.

BARNEY: It was so scary to come out with those pictures about the upper class. If you look at the reviews at the time, the critics only focused on their own fascination with the upper class. They never talked about the actual pictures. And that killed me, although I don’t think they were being nasty. I think they were just saying this was the first time anyone had revealed the upper class, and then they went on to describe it, but they never talked about the things in the work that were really interesting to me. That will always sort of identify me, but on the other hand, that’s why I made them big. I wanted people to be able to see the cereal box, the kind of dress, the kind of curtain. Those details fascinated people. I compare it to when audiences first saw that TV series Dallas, their being fascinated by a world they did not know.

HOMES: It’s so striking and disarming to be confronted by a family portrait printed big.

BARNEY: Definitely. It’s very revealing.

HOMES: Your work has so many painterly elements to it, but you’re not a painter.

BARNEY: No, but I have been surrounded by art all my life. My mother was a terrific artist. The fact that my pictures are about families is kind of motherly.

HOMES: [The writer] Grace Paley acknowledged that women often write about the domestic and the intimate interior, while men write about big social landscapes, although that’s not really true anymore. When you shoot your subjects inside, how close are you to them physically?

BARNEY: I am close to these people. I wasn’t in the first years because I wanted to show the interiors. But then each year I got physically closer because I wanted the picture to feel more personal. But wherever I’m photographing, I still feel as if I’m looking from a distance. I’m really a voyeur, examining everything. I don’t mean I’m being critical. But even as I’ve grown closer, I’m backing up to an extent. I myself am very private. I keep my distance. Some of that has to do with fear—of letting somebody in and them knowing too much about me.

HOMES: That part of intimacy is always hard. Was the recognition you received as an artist difficult for you?

BARNEY: Very much so. I never thought that my work was going to become well-known. It started happening slowly, without my realizing it. But when I did, it was terrifying. I still can’t believe that people let me photograph them. The trust is amazing. But I’ve always put them in a context that is dignified, and that’s really important.

HOMES: What are your thoughts on iPhone photography?

BARNEY: People aren’t really looking at the result. And they don’t print it. So to me, it’s almost not a photograph. It’s like looking in the mirror. It’s a tool I don’t relate to at all.

HOMES: But has it changed your subjects’ relationship to you? I imagine it’s even changed people’s natural gestures when they know they’re being photographed.

BARNEY: That depends on your definition of gesture. I’ve thought of it literally as what you’re doing with your hands or your body, which suggests what you’re thinking about or who you are. Some of that is hereditary and handed down, and some is newly learned.

HOMES: You took a photograph of two generations of hands [The Hands, 2002] shot in front of a painting in an interior that is beautiful. I once sent my mother a photograph of my daughter when she was very young, and my mother said, “She has your grandmother’s expression on her face right now.” I loved that.

BARNEY: I also think people imitate actors—things they’ve seen in a movie or on TV, and before you know it, they’re doing something with their face or their mouth. It’s from some actor they think is cool. They might not even know they’re doing it, which is kind of funny.

HOMES: To me, you are the best at capturing what I would call a psychosocial expression of history and of experience and of class.

BARNEY: And the history of a particular family. I feel as if most people are pretty much the same within a certain class, due to the schools they attend and the way they are raised.

HOMES: You are like the Margaret Mead of photography.

BARNEY: Oh my god. I used to be so interested in anthropology that I’d go to the Margaret Mead Film Festival, and they’d screen these old black-and-white movies with women sitting around in a circle. The subtitles would have them saying, “My husband, he’s so lazy. He never takes out the garbage.” It’s exactly the same thing happening in Greenwich, Connecticut, with women in their Prada clothes. I know that’s very simplistic but—

HOMES: But it’s also basic human behavior. Is ritual or tradition important to you?

BARNEY: Oh god, yeah, especially the repetitions of birthday parties and christenings and weddings, and going out to buy a pumpkin or a Christmas tree. I think kids love those repetitions because they’re comforting.

HOMES: Even if stuff is going badly, those are the things we do. As an artist, what do you feed on? What do you consume for your own artistic life?

BARNEY: I look at art all the time. I go to the museums and galleries every week. That really is like food for me. And I go to the movies a lot. Lately, I’ve been trying to work in film, some Super 8, which I find hard but also enjoy. I’m filming the people I’ve photographed. It’s silent, and I’m curious how they look when they’re talking. I don’t know if I want to show it. But I’ve been working on a number of other projects. I’m finishing up Youth, and I’ve been doing landscapes, which I haven’t done in many years. I photographed some nudes for a couple of years that I might go back to.

HOMES: Maybe a nude in a landscape?

BARNEY: Actually, nudes are much more interior to me. But you never know. I also draw and paint. For 20 years, I’ve been drawing and painting snapshots from my family, as well as from my own work. I do them in pastel, watercolor, crayon, and pencil. Nobody knows about that. Even me. I always forget all about it.

A.M. HOMES IS A NEW YORK-BASED WRITER. HER NEW BOOK OF SHORT STORIES IS DUE OUT IN SPRING 2018.