MADAME

Vaginal Davis Opens Up

Vaginal Davis wears Sunglasses Vaginal’s Own.

I first encountered Vaginal Davis at a poetry reading in Los Angeles in 1992. The self-described Blacktress, literary figurine, and spokesmodel appeared in heels and a maroon choir robe, singing, “When you get caught between the moon and New York City” while shaking a Mickey Mouse tambourine. Her first poem consisted of the word “girl” pronounced in as many different ways as there are Inuit words for “snow.” She passed out copies of Fertile LaToyah Jackson (her publishing venture) and read some of the zine’s fan mail. (“Dear Miss Jackson, you are evil…”) Wildly inventive and uncategorizable? I didn’t know the half of it. I didn’t yet know about her videos like The White to Be Angry, her art-punk bands like the Afro Sisters, or her portraits made from eyeliner, lip stain, and other beauty products. And there’s so much more. Vag (pronounced Vaj) absconded to Berlin decades ago, and her work has only deepened. A comprehensive exhibition, “Magnificent Product,” opens at MoMA PS1 in October after an earlier iteration at Gropius Bau, Berlin. Critic José Esteban Muñoz once described her work as “terrorist drag,” explaining, “Terrorist, insofar as she is performing the nation’s internal terrors around race, gender, and sexuality.” When I spoke to her over Zoom, we discussed her tendency to take on all the problems of the world, her friendship with Warhol superstar Holly Woodlawn, and her life in Berlin.

———

TUESDAY 5 PM JUNE 24, 2025 BERLIN

VAGINAL DAVIS: Hi, darling.

CYNTHIA CARR: So great to see you, if only on a screen. How are you?

DAVIS: I’m doing okay for a 64-year-old with Type 1 diabetes. I’m trying to smile through it.

CARR: Good. And I hear your show is doing great at Gropius Bau.

DAVIS: They just told me that it’s been breaking records. So far they’ve had 30,000 guests.

CARR: Wow. And the show’s coming to PS1, right?

DAVIS: Yes. But it’s going to look different because PS1’s a lot smaller than Gropius Bau. There’s going to be six installations in one room, and then the CHEAP Collective installation, “Choose Mutation,” in a separate room.

CARR: I wanted to ask you about the CHEAP Collective. What’s cheap about it?

DAVIS: We’re the CHEAPies. The very first CHEAP Collective production was in 2001 in Berlin. It was a performance piece saluting Hollywood actress Carmen Miranda and [filmmaker] Jack Smith. At that point, I was like a special guest brought in from Los Angeles, and Ronald Tavel, who wrote those early Warhol films and was living in Bangkok at the time, was also brought in as a special guest. Then the CHEAP Collective did a regular club night in Berlin, and I was always invited in to do things with them. I’d be going back and forth from Los Angeles to Berlin. Then, after I got gentrified out of my big, beautiful apartment in Koreatown in L.A., my comrades in arms at the CHEAP Collective said, “Why don’t you move to Berlin?” I figured, what have I got to lose? I’ve never learned how to drive a car, even though I’m from the city of cars. I don’t have a relationship. It’s not like I have a husband or anything, and most of my family members are dead. What’s keeping me in tired Los Angeles?

Dress and Top (worn as headpiece) Lou De Bètoly.

CARR: Especially now, with what’s happening there under Trump.

DAVIS: Oh my god, the whole country. I left at the perfect time, which was 2005, and I did not look back, lest I turn into a pillar of salt. It was the best decision I ever made. I’m celebrating 20 years being in Berlin and 26 years with the CHEAP Collective. I wanted to tell you that I read your book on Candy Darling, and it is incredible. I thought I knew a lot about her, but I didn’t know that poor Candy didn’t really have a home. Here she was a superstar, and she was just couch surfing, going from person to person, and sometimes going back to her mother in Long Island.

CARR: Was she important to you in some way?

DAVIS: Of course. That triumvirate—Holly Woodlawn, Candy, and Jackie Curtis—were big influences on me. Those three ladies were really something else. And Holly, she left New York in the early ’80s, I believe, and went to Los Angeles. She used to work at a store on Melrose Avenue. You remember Melrose Avenue, the punk rock avenue in Los Angeles?

CARR: Yes.

DAVIS: Well, I used to work and do the windows at this store called Retail Slut. And Holly worked just up the street from me at Soap Plant and Wacko. I’ve known Holly ever since. Right before she died, the CHEAP Collective—[founders] Susanne Sachsse and Marc Siegel—curated an art conference called Camp Anti-Camp: The Queer Guide to Everyday Life. And one of the main guests was the legendary Holly Woodlawn. That was her last big performance. She was just sublime. My makeup artist at the time, Akira Knightley, did her makeup and made her look so heavenly and so gorgeous. She just inspired the Berlin community. So your book meant a lot to me. Do you remember, I was doing this performance piece at NYU called “Vaginal Davis Is Speaking From the Perineum,” and you were in this talk show installation?

CARR: I remember. I first saw you in 1992 at the gay bookstore on Santa Monica Boulevard. And I acquired a copy of Fertile LaToyah Jackson Magazine [Vaginal’s zine that ran from the early ’80s to the late ’90s]. Then at NYU in 2014, I was on “Speaking From the Perineum.” But I can’t remember what I talked about.

DAVIS: It was about the Athletic Model Guild photographer Bob Mizer, because NYU’s Washington Square East [80WSE Gallery] was curating this exhibition about him.

CARR: Oh right.

DAVIS: Then, back in 2010, I did “Vaginal Davis Is Speaking From the Diaphragm,” a talk show installation at PS 122. I was a big lover of talk shows from the ’60s and ’70s. I’m old enough to remember The Joey Bishop Show and the very gay Merv Griffin. And remember The Mike Douglas Show from Philadelphia? For a whole week [in 1972], he had, as his co-hosts, John Lennon and Yoko Ono. This Middle America audience was just blown away by Yoko’s singing. They were looking at her like, “What’s going on here?” I wasn’t such a huge fan of the Beatles, but I loved Yoko. And now at my exhibit at the Bau, on the ground floor are my installations, and on the first floor are Yoko’s installations. But when I did “Speaking From the Diaphragm” at PS 122, I brought in people from all walks of life—from the theater world, art, fashion, film. I even had people who were selling insurance, because a lot of talk shows in the ’60s and ’70s would have a normal person on, talking with celebrities. I wanted to bring that flavor back, where it’s not just about some celebrity trying to pitch their latest movie.

CARR: Now that all seems like more innocent times.

DAVIS: It seems like now the entire world is falling apart. And it’s very difficult to make art in this morass. I felt that I took on all the problems of the world as a child. When I was about seven or eight, I started being pen pals with other kids around the world. The thing that struck me was that other young children were so much more politically aware than children here in the United States, because everything is kept from us. That’s still part of my art practice. I still write letters the old-fashioned way. Whenever I teach at universities and art schools, I get the young students to write letters. I don’t teach theory, I teach doing by doing, which I stole from the legendary performance artist Rachel Rosenthal.

The Wicked Pavilion, 2021. Installation view of Vaginal Davis: Magnificent Product, Moderna Museet, May 15–Oct. 13, 2024. Photo: My Matson. Courtesy of Moderna Museet.

CARR: I know you think of her as a mentor, but her work is so different from yours.

DAVIS: It’s completely different. She was one of the first performance artists to deal with environmental issues. No one else was doing performances on such a grand scale. She was the ultimate grand madame, and now that I’m older, I see myself as a grand madame.

CARR: Right.

DAVIS: One of the legendary grand madames is Diana Vreeland. The adage she wrote, “There is elegance in refusal,” I live by it. My mother was a firm believer in saying no. I have four older sisters, and I was the baby in a Black Creole family from Louisiana. My mother’s mother was a full Choctaw Indian woman who grew up on a reservation. That’s why I have these high cheekbones. Thank goodness for them. My mother left the Deep South to move to Southern California, but it was almost the same because a lot of Southerners moved there for the weather. They had these covenant laws where people of color could only live in certain parts of Los Angeles—Watts being one of the areas, and East Los Angeles being another. It wasn’t until Nat King Cole disrupted all that, when he bought a house in the old-money enclave of Hancock Park. Boy, did they want to lynch him when he went there. But he was defiant, and he stayed there until he died. Did you know that Berlin has officially been the sister city to Los Angeles since 1967?

CARR: Really? I didn’t know that.

DAVIS: They’re similar in that there are few natives born to the area, but many people who migrate there. I’ve been living here for 20 years, and I never imagined that I would have a solo museum show.

CARR: You were also in a show at the New Museum in 2017, right? It was all gay, trans, and queer artists. You had a piece there made from makeup. I remember it as an abstract piece, and I thought it was one of the best things in that show.

DAVIS: A lot of people know me as a performance artist and writer, but don’t know that I painted, made sculptures, and whatnot. The show at the New Museum was called Trigger. Those relief sculptures made out of makeup and clay were first exhibited as a solo show in 2015. As the CHEAP Collective, we did our first performance piece in New York that year. Susanne Sachsse, the fearless leader of CHEAP, directed the piece. I wrote the libretto. Then Jamie Stewart of the avant-garde music group Xiu Xiu did the music. It was a version of The Magic Flute. But I discarded the Mozart music, and I had Jamie write an original score. Then I wrote a crazed, disjointed, deconstructed libretto. The gallery had six different rooms. It was a performative installation. The audience would go through every room accompanied by Susanne Sachsse. She was Heidi, and I was the twin sister Heiki. It was a bit convoluted, but somehow, it worked.

CARR: Mm-hmm.

DAVIS: I’m known for being part of the punk world, but one of my early influences was actually grand opera. The very first opera that I got to see as a child was Mozart’s The Magic Flute at the old Shrine Auditorium. I got to see that because I was in a special program for gifted children called MGM, which stood for “Mentally Gifted Minors.” Back in the ’60s and ’70s, there was still a social consciousness, which is eradicated now. I was part of the last generation that benefited from this social consciousness for poor, underprivileged kids who could get all this special stuff in public school. One of the reasons why I’m still alive today and not in jail or dead is because I was put in special classes. If I hadn’t had that, I certainly wouldn’t have become an artist having solo shows in museums.

CARR: Why is the new show called Magnificent Product?

DAVIS: It refers to an advertisement that was in this very famous Korean-owned wig store on Hollywood Boulevard, Ms. Ellen’s Hollywood Wigs. Everyone who got dressed up got their wigs from Ms. Ellen because the prices were amazing and the quality was incredible. For the longest time, her false eyelashes were a dollar a pop. Can’t beat that. In her shop was a faded advertisement from maybe the early ’70s for some kind of Black hair-care product called “Magnificent Product.” The advertisement was this gorgeous, serene, graceful Black lady with a big Afro who looked so fierce and so determined. I was in the store buying some wigs, and I said, “Oh, Ms. Ellen, can I have this advertisement?” She said, “Yeah, take it.” That’s how I made my zine. I would type things on a 1920s portable typewriter and cut and paste flyers with rubber cement. I used the words “magnificent product” for the album we were recording for my then–performance group called the Afro Sisters. The album was never released, but I always said I’ve got to use that title. After PS1, I think the show is going to my birth city of Los Angeles. But I never believe anything’s going to happen until it actually does. My mother, Mary Magdalene de Plantier, used to say, “Honey, there’s no guarantees in this world or the next,” and it’s so true. Who knows what’s going to happen with all these insane men ruling the world.

CARR: PS1 is part of MoMA. Do you think of yourself as entering the mainstream now?

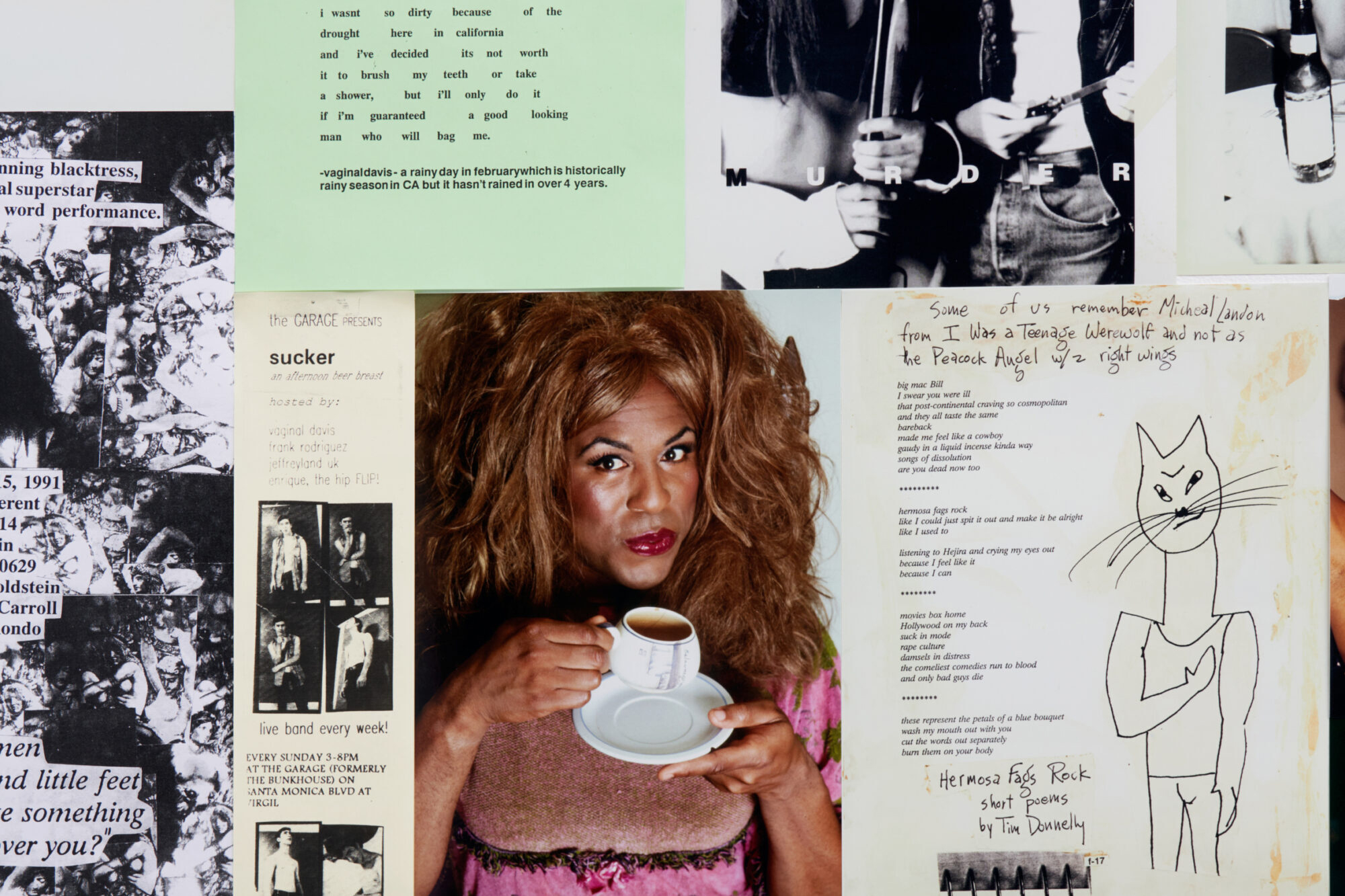

Memorabilia and ephemera from The Wicked Pavilion, 2021. Installation view, Eden Eden, Berlin, 2021. Photo: GRAYSC. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin. © Vaginal Davis.

DAVIS: That’s a prostate-probing question. I never thought that I would because I would do my little art projects and then move on to the next thing. I didn’t save anything. I didn’t even have any copies of my zines. If it weren’t for friends of mine who saved some art objects and all this weird ephemera, it wouldn’t have wound up in the show. You know, when I moved to Berlin, I came with one suitcase and not even $100 in my pocket.

CARR: Since moving to Berlin, have you kept up with your bands like Afro Sisters, Cholita!, and Pedro, Muriel & Esther?

DAVIS: A lot of my bands have gone on hiatus. But never say never. We may reemerge. I’ve started some art bands here in Berlin—one called Tenderloin, and another with the CHEAP Collective called Ruth Fischer. I don’t know if you know who Ruth Fischer is.

CARR: No.

DAVIS: She was [composer] Hanns Eisler’s sister, and she worked for the CIA at one point. She was in charge of the Communist Party of Germany. One of our songs says, “I’m a communist/I’m a communist/I worked for the CIA/I’m a communist/I’m a communist/Not part-time, but every day.” Ruth Fischer has gone in and out of hiatus over the years, but it somehow always reemerges.

CARR: Did you know German when you moved to Berlin?

DAVIS: I had studied German because I was an English literature major and a minor in philosophy, and you had to have a prerequisite in Deutsch. But I didn’t expect to actually use it outside of referencing German philosophers. When I moved here, I took a refresher course. My mother’s native tongue is French, but she never spoke French to me. She wanted a language to talk to my sister so that the baby couldn’t understand. So I actually had to take French in school. I have a Mexican-born father, and like most Americans, I also have a German background because those German immigrants really got around. My father was born in Mexico City, but his mother was a German Jewish woman from Austria. And his father was actually born here in Berlin. He was a Protestant who broke the rules and married a Jewish woman. And they fled. They saw the writing on the wall. They weren’t allowed to come to the United States, but they were able to go to Mexico. My father was 19 when he met my mother, who was in her forties. They were never married. I’m an illegitimate child. And this isn’t mythology: They fornicated at a Ray Charles concert under those round tables at the Hollywood Palladium. And then nine months later, I was the rip heard ’round the world.

CARR: I saw that one of the installations in your show is a large penis in a pink bed in a pink room.

DAVIS: I’ll just say that that particular installation is a stylized rendition of what my bedroom was like when I was a tween. I’ve always loved pink. It’s a color that turns up in almost everything I do. Pink and the colors chartreuse and pistachio, those 1950s colors. I was always collecting imagery. I would put up clotheslines and hang images of whoever my crushes were at the time and whatnot. And the crushes weren’t just pop stars. They could also be literary people or people from the world of science. Because back in the ’70s and the ’80s, a lot of different worlds collided. That’s how Los Angeles was: the mixing of people from different cultures, different classes, which you don’t really have so much now. Once I got involved in the punk scene—a lot of the kids in the punk scene were the children of movie stars. Then when I went to UCLA, oh my god, there were all these rich kids, people who were in a different stratosphere than me. I was kind of jealous and had this sort of “I hate the rich, blah, blah, blah.” But then when I got to know some of these people, I felt sorry for them because so much of their relationships were transactional. They don’t have it as easy as you think. I did have a very unusual childhood and family, but it was very loving.

CARR: I know that your mother was a big influence. Are you coming to New York for the show?

DAVIS: I hope to be. Who knows what’s going to happen between now and September with the Orange Roughy in charge and his sidekick, the Space Karen, and their army of enablers and psychopaths. It’s very, very, very frightening. That’s why we all have to stay close to all our friends and our loved ones, because we can find joy with these people. And that’s so, so important right now.

CARR: I agree.

DAVIS: We shouldn’t go into despair. We have to be vigilant. You have to fight all the time. It’s a struggle that never ends.

———

Hair: Ruby Howes using Oribe at Shotview Management.

Makeup: Christian Fritzenwanker using Fenty Beauty.

Nails: Camilla Volbert.

Photography Assistants: Andreas Musculus and Bendek Tikk.

Fashion Assistant: Ivanna Torres.