STUDIO VISIT

For the Artist Gala Porras-Kim, Sculpture Is a Portal to the Afterlife

I fell wildly, urgently in love with Gala Porras-Kim’s work in a Seoul museum, where I saw a replica she made of a sarcophagus held in the British Museum. Taking seriously the beliefs of ancient Egyptians, who built doors facing east to let the dead see the sunrise, Porras-Kim proposed that the British Museum turn their sarcophagus east and wrote a letter explaining why. “Since we cannot yet be certain of the mechanics of the afterlife,” she wrote, “we could consider the perpetual plans of the persons under your charge as a guide for their care and, as such, in their display.”

Other work she exhibited at that museum showed ever-beguiling ways of imagining beyond the usual stalemates in the fights to repatriate what’s often considered stolen art. Since I’m writing a heist novel about Korean artifacts, I thought, “Who is this brilliant person? I must talk to her.” So I did, meeting Porras-Kim in her studio days before she’d fly to Seoul to install a show at the major art gallery Kukje, where her work will be on view through the end of October. For those of you not in Seoul, Porras-Kim’s work is on view among collections at the Whitney, MOMA, and LACMA. But really, if you haven’t yet, keep an eye out: before long, you’re going to see her work everywhere.

———

R.O. KWON: I was looking at a few of your recent posts on your Instagram, and you said something so beautiful, that drawing as a medium has helped you slow down time.

GALA PORRAS-Kim: I almost feel like a high-achieving multitasker: I can do five things at the same time really well, but not one thing perfectly. When I think about my time, I wish I could spend one month growing one tomato, and eat it, but I can’t. So I was thinking about what things I can actually control. With my main job, which is art-making, I can choose to build in a time frame in which I can slow down my own time so that I can understand the subject better. Because the drawings take so long to render, you see all of the cracks in the pot. People ask me, “Why not photographs?”

KWON: Yeah.

PORRAS-KIM: They’re photorealistic, so it would look the same, but for me, as an author, I’m the first viewer of that work. And when I make the work, I am its first audience, so I can see all of the subjects of the drawings first. I think that the audience can also tell. If they come and see a photograph versus a drawing, immediately they can tell it took a long time. I do work with a team now, but you just have to have a lot of patience.

KWON: One of my favorite thinkers is Simone Weil. She converted to Catholicism later in life, and one of her lines is, “Attention is the highest form of prayer.”

PORRAS-KIM: Yeah. Also, when I’m drawing, a pencil has a tip, so it feels like such a perverted medium because you’re looking at every single tiny pore of this object, every single pixel. Painting involves this many bristles, so you can cover more ground.

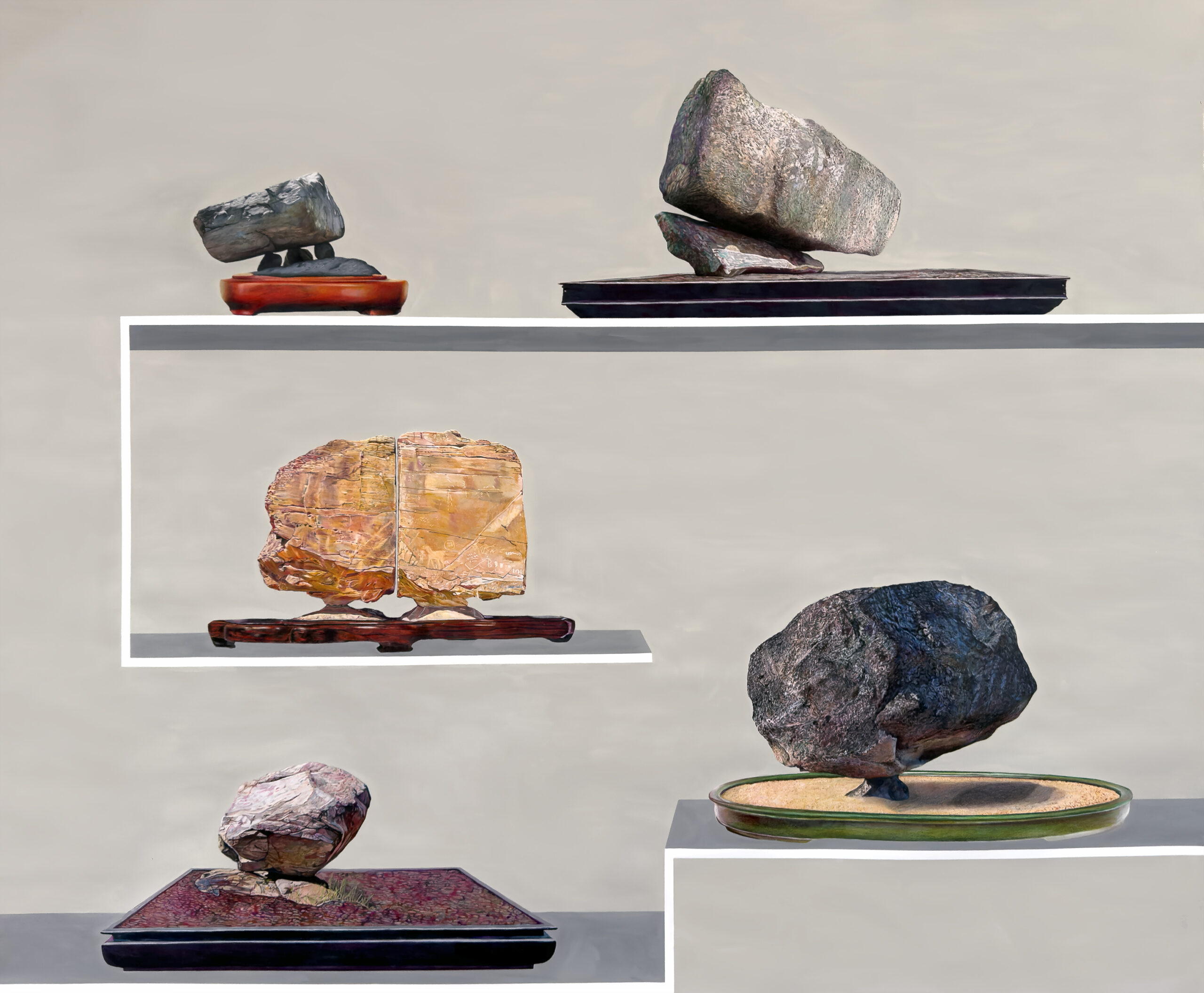

Installation view of Conditions for holding a natural form. Image provided by Gala Porras-Kim.

KWON: [Laughs] Yeah. I find your work so intensely moving, for a variety of reasons. One reason is the respect you seem to have for objects, regardless of how they’re valued by the outside world. I’m thinking of the attention you’ve paid in your drawings to objects like a museum’s tags for artifacts, and how you’ve focused on these tags as items worthy of notice. You’ve also been working on a piece for which you put out a question to museum curators about–

PORRAS-KIM: Oh, about what’s least likely to be on view.

KWON: Yes, the artwork least likely to be shown in public. What drew you to that idea?

PORRAS-KIM: It’s not necessarily that the object itself has agency. It’s more thinking about a material in relation to other things. Not just to people, it could be a material in relationship to mold, or to spirit. It’s not necessarily that I’m thinking, “Oh, this object has its own will,” but how do we respect previous relationships that this object had that are still relevant today? Because some of them don’t expire. For example, the material relationship between a stone and the mountain it was a part of. Even if that rock goes away from the mountain, they’re still connected, and they live in a different timeline because mountain time is different from human time.

KWON: Yeah.

PORRAS-KIM: So, in a sense it’s about recognizing the characteristics of these different types of relationships. When you understand that this object is also functioning as other things for these previous iterations of its life, then we can toggle the iterations: “This relationship is more important, and this one is less important.” The relationship of a material to a dead person who needs it for their afterlife, I think, is more important than it being a paperweight for someone right now. Even though it is functioning as these multiple things.

KWON: I grew up extremely Christian, then left the faith. It’s the pivotal loss of my life, and it’s left me so afraid of death. I spent formative years believing I was going to have life everlasting, and so was everyone I love. And now, when I get extra depressed about the state of the world, I like reading articles for laypeople about quantum physics. One of the physics ideas I find to be intensely appealing is the possibility that we all came from one thing, and then we burst out, and so we all belong to each other. I wonder if ideas around this kind of belonging are attractive to you.

15 Rocks from outer space, 2025. Colored pencil and Flashe on paper. 182.9 x 228.6 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Kukje Gallery. Photo: Gala Porras-Kim Studio. Image provided by Kukje Gallery.

PORRAS-KIM: I think belonging is strange, because then it feels like you own something. You know what I mean? There’s a responsibility, and then it feels like it trickles down into insurance and liability and ownership and borders. I like to think about things more relatively. Yes, we might be one thing, but we are relative to this particular timeframe in the bigger picture. And then, we will turn into mold, and that will be our next timeframe, still us in a different shape. So, in that sense, yes, I can understand that we could be all one tight chain at different stages. Like this cactus [gestures]— if I eat it, it’ll become part of me.

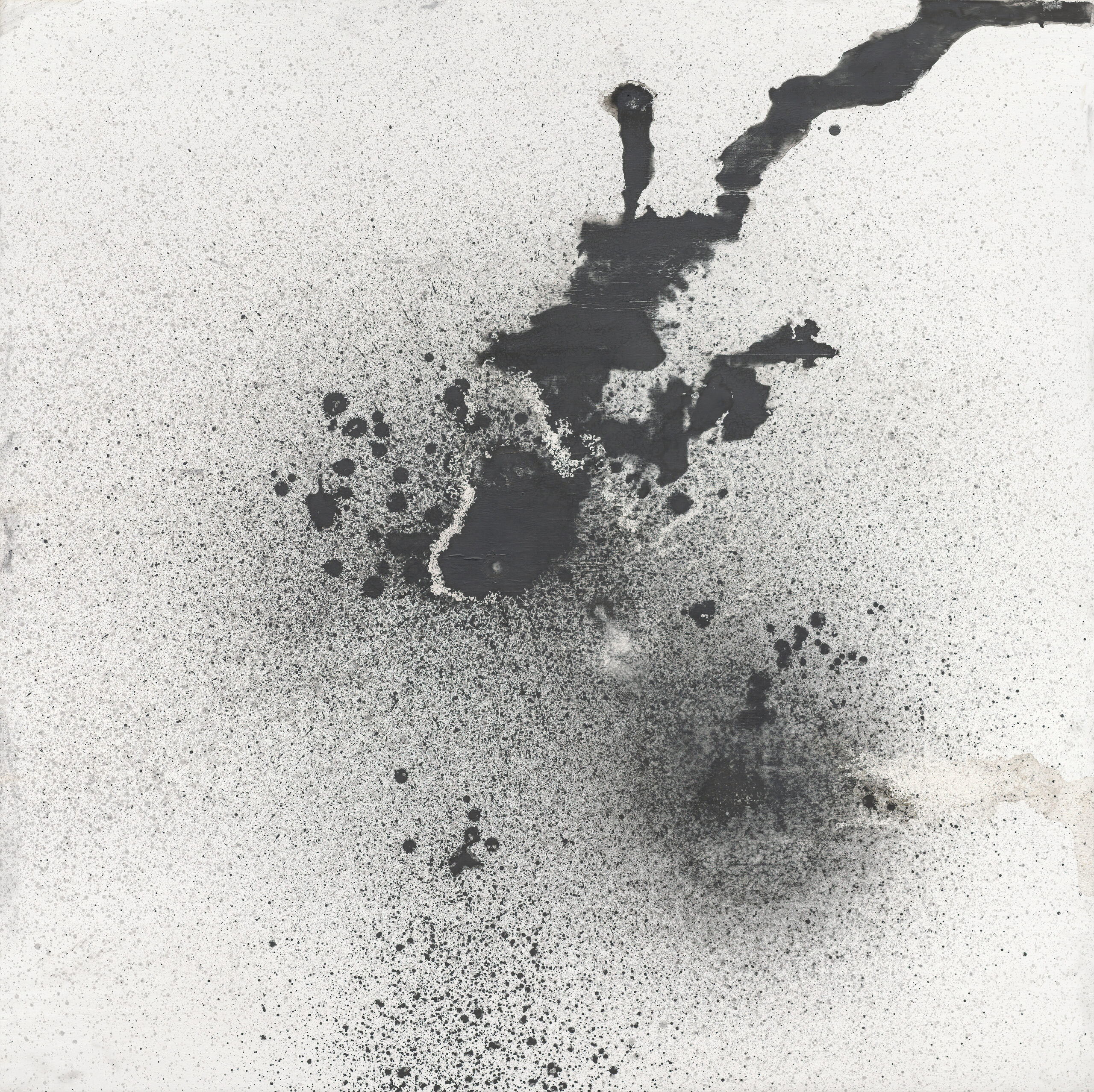

KWON: Speaking of timeframes, I love A terminal escape from the place that binds us, the ink-stain work you made after seeing ancient people’s bodies in a museum in Gwangju, Korea. You made the ink stains with the stated hope of asking the spirits of these bodies where they’d like their remains to be. I saw that it’s a series, a question you’ve continued asking.

PORRAS-KIM: Yes.

KWON: So, why did you turn to encromancy, or ink-stain divination? How did you first get there?

PORRAS-KIM: Encromancy is not itself the subject of the work because I’m not a witch, but we thought, “How does an abstract form create some uncontrollable logical meaning for us? Through this abstraction we will find something.” Then I thought, well, abstraction is part of art making. And so I can make a process in which we’ll create an abstract form that can’t have every variable controlled. I mean, I can control the dimension, the color, the size. But the form itself is being controlled by the temperature, or the gravity. We don’t necessarily know if we can or cannot communicate with the afterlife. I have no idea. I know that I don’t know it doesn’t work.

Signal (Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporáneo 03/09/23-09/03/23), 2023. Graphite on gessoed panel. 182.9 x 182.9 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Kukje Gallery. Photo: Chunho An. Image provided by Kukje Gallery.

KWON: Yeah.

PORRAS-KIM: That’s kind of how I think about spiritual things. People think I’m a really spiritual person, but I’m thinking more that if I don’t know, I can’t say it doesn’t work. So, when you think about all of these people in the past who were really, really certain that their version of an afterlife was going to happen for them — why would I take my version of not knowing over the certainty of someone in the past? When you think about the ancient Egyptians, they put so much energy and resources into planning their afterlife. So why, when we see their objects in the museum, do we think that our version is more legitimate than theirs?

KWON: I read that you had considered working with a Korean shaman, a mudang?

PORRAS-KIM: Yeah. We thought, “Well, what are existing ways of communicating with people in the afterlife?” Then we decided with the curator that we wouldn’t go that way, because we don’t know when this person lived, and it was probably pre-Korea, pre-mudang. Which type of cell phone model are we going to use? [Laughs] If we picked working with a shaman, it would be too resolved. And I don’t want to make it seem like I know anything, because I don’t. None of the work in A terminal escape from the place that binds us is about a solution. There’s no result. Abstraction is a form, but I don’t know how to read those abstractions. It’s more like, “There is a landscape in here, and we don’t need to know how to read it because it’s not even for me.”

KWON: Oh, that’s so beautiful. With this work, have you ever experienced any – I don’t even know what I would call it. I’m agnostic, and I’m with you: I know what I don’t know. But have you ever had any dreams, any emanations?

PORRAS-KIM: I think that making these projects has helped me figure out my own logical boundary. I’m a very logical person and I get put off by a lot of spiritual things. But these works help me recalibrate my own relationship to things I don’t know, and to argue with myself, like, “Why do you feel like this is cringe?” So it’s not necessarily as direct as a dream. But it’s helping me rearrange my brain so that my thinking can include a more spiritual life, because I can’t logic my way out of it.

Installation view of Gala Porras-Kim’s solo exhibition. Conditions for holding a natural form at Kukje Gallery K1. Image provided by Kukje Gallery.

KWON: Yeah.

PORRAS-KIM: But I think that has helped me be like, “I don’t need to know everything. It’s actually fine not to know because I will know once I’m mold what it is to live more in nature.” Because, in my current life, I feel so removed from nature. I’m a mammal first and then a person. But it feels like the order has changed so much. We live on concrete, you know?

KWON: Yeah. I was delighted by everything you did that had to do with the Mayan rain god Chaac, and Harvard Peabody Museum’s collection of objects that Mayans had dropped in a sacred cenote as offerings to the god. I laughed when I read that you considered suing on behalf of the rain god, and that, instead of suing, you instead asked them to acknowledge that the objects are on loan from Chaac. You also made work focusing on the dryness of the Peabody’s conservation, comparing the museum’s environment to the water-filled cenote in which the objects had existed for centuries. I wonder if you can talk about what led you toward the path of loans and water, and not the path of suing?

PORRAS-KIM: When I made the proposal for that work, which was attached to a fellowship at Harvard’s Radcliffe Institute, I was like, “Harvard has great lawyers and I want to make this new project.” I was going to spend a year reading about the law, which I’m really interested in, because law and policy make boundaries for materials in the world, the same way that we as artists make boundaries for material. It’s just more collective in law and policy. If trees were all made into legal artworks, then nobody could touch them. They would come with conservation notes, et cetera. It turned out that a conservation project was more interesting because of the specificity of the cenote being in water and the museum’s storage being dry, and I thought, “This is a moisture work more than a legal work.” The legal work can take place in a different way. The cenote is a placeholder for many objects that are being kept in storage, objects that have similar relationships to the spiritual and religious.

KWON: You’ve said in various ways that — well, so much of your work involves a kind of letting go —

6 Balanced stones, 2025. Colored pencil and Flashe on paper. 152.4 x 182.9 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Kukje Gallery. Photo: Gala Porras-Kim Studio. Image provided by Kukje Gallery.

PORRAS-KIM: Mm-hmm.

KWON: Does this mean that you’re good at giving up control?

PORRAS-KIM: No.

KWON: [Laughs.]

PORRAS-KIM: Absolutely not. I’m working through this, thinking through how to let go. It helps me. I think that’s why audiences respond well to the work, because I have these same anxieties. I think about institutional collections, but in relationship to my own home objects. I had a hoarding problem. I love collecting. But how do you think about what you keep? They’re the same types of anxieties you have in your day-to-day life, but then it becomes institutional, through more generations. It’s more collective.

KWON: I’m curious about the letters you’ve sent to institutions asking, “How about you? How about turning the sarcophagus just a little bit to align with this ancient Egyptian’s clearly described religious beliefs?” And it sounds as though very few institutions have taken you up on what seemed like reasonable proposals. Is that more or less what you expected?

PORRAS-KIM: The letters are an artwork, so they are constructed, in a way, for the viewer. So I’ve sent a hundred emails to these directors before those letters. The exhibition copy is an artwork in itself. But those conversations are still ongoing. For example, for the Gwangju work, I sent that letter during COVID, so I never physically met the woman. It was mediated through curators. But I met her at the opening. She came out and she’s like, “I got your letter.” [Laughs.]

KWON: Oh my gosh.

PORRAS-KIM: I think it’s not that these institutions are not already thinking about these things, it’s just that their policy doesn’t allow them to actually move forward into any change. For example, with the sarcophagus, it seems easy, but it’s not, because they’re thinking, “What about the wheelchair accessibility of this aisle?” So there are contemporary reasons why.

Installation view of Gala Porras-Kim’s solo exhibition. Conditions for holding a natural form at Kukje Gallery K1. Image provided by Kukje Gallery.

KWON: I remember thinking, from the first time I saw a dead body in a museum—

PORRAS-KIM: You know.

KWON: I thought “If I were that dead body, I’d be furious.”

PORRAS-KIM: Exactly. And if you were their kid—those people have kids! And families.

KWON: Yes. And of course, there are ongoing disputes about this, and people are fighting for the return of their own relatives’ bodies.

PORRAS-KIM: I think that looking at the law here is also very interesting, because the question is, “When does a cadaver become old enough to stop being related to living people? And is it old enough to be archaeological?” And every country has different laws. For example, in some countries it’s like, “When the body has been eaten enough that it’s unrecognizable, it becomes archeological.” So the maggots determine the border between cadaver and archeology. Or in some places in Europe–I think Italy says that people who died after World War I can still be cadavers before they are “old enough” to be archaeological.

KWON: That’s fascinating.

PORRAS-KIM: Italy is… they’re Catholic. They’re thinking about that. But this legal caveat has arranged the way that people categorize matter, the same matter. So, that can change your spiritual view on things? It’s very interesting to me.

KWON: Wow. Yeah, Catholics, the sanctity of the body, it’s a big part of Catholicism–

PORRAS-KIM: Yeah. But pre-World War I–

KWON: No more.

PORRAS-KIM: Unless it was a murder victim, then there’s a loophole.

KWON: What? So Italian murder victims from before World War I have the rights of bodies, of cadavers?

PORRAS-KIM: It changes per country and probably per administration.

KWON: This is fascinating.