IN CONVERSATION

When Mary Boone and Julian Schnabel Ran New York

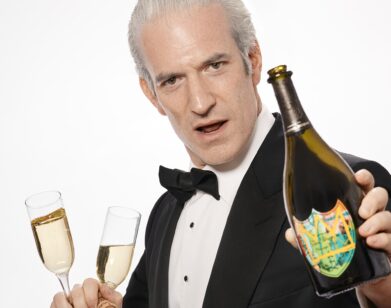

Julian Schnabel and Mary Boone, photographed by Ben Taylor.

In a trip down memory lane last week, Mary Boone and Julian Schnabel traveled far and wide, from Max’s Kansas City and the Cedar Bar to Ocean Club and Christ Cella, lighting up each bygone hotspot with memories of the artists who crossed their paths. They recounted trading paintings with Andy Warhol; the night Brice Marden took a swing at Schnabel; the time a painting fell off the wall and landed on Patrick Lannan; and the mischievous exploits of Sigmar Polke, who would run wild around Manhattan licking public windows to startle strangers on the other side.

The era left an indelible mark, paving the way for a litany of artists whose internecine scandals and rivalries were just as much a source of intrigue as the work itself. It’s no wonder that Boone, after a five-year hiatus from the art world (and a minor stint behind bars for tax fraud) has chosen to revisit the halcyon days with Downtown/Uptown: New York in the Eighties, an all-star group show she’s guest curated at Lévy Gorvy Dayan’s Beaux-Arts townhouse. On view through December 13th, the show features works by Schnabel, Francesco Clemente, Eric Fischl, Ross Bleckner, Jeff Koons, and Cady Nolan, to name a few. To mark her welcome return, Boone and Schnabel took a plunge headfirst into their unruly and decadent pasts.

———

JULIAN SCHNABEL: Well, here we are. Hi, Mary.

MARY BOONE: Hi, Julian. Just like old times. Is this your studio?

SCHNABEL: Yeah.

BOONE: Oh, good. I didn’t recognize the painting behind you.

SCHNABEL: You’ve never seen the painting behind me.

BOONE: But I’ve never seen anything like it before.

SCHNABEL: That’s good. That’s was the whole goal for doing it, doing something that I’ve never done before.

BOONE: So, are you working on a new movie? Is that what I heard?

Installation view of Downtown/Uptown: New York in the Eighties. Courtesy of Lévy Gorvy Dayan, photos by Elisabeth Bernstein.

SCHNABEL: I made a movie called In the Hand of Dante. We just showed it at the Venice Film Festival last Wednesday. I was given this award, Glory to the Filmmaker there.

BOONE: That’s great.

SCHNABEL: I just came back to the city. I was painting out in Montauk and brought all the works here. I only saw them inside for the first time two days ago.

BOONE: So, you were painting all that time outside?

SCHNABEL: Yes. I keep going. That’s what I do. I’m always painting.

BOONE: So, what about the movie, though?

SCHNABEL: What about the movie? Why don’t we talk about painting?

BOONE: Okay.

SCHNABEL: Basically, the movie takes place in the 14th century and the 21st century, and it’s called In the Hand of Dante. It’s based on Nick Tosches’ book from 2002.

BOONE: Okay, I will see it.

SCHNABEL: I don’t know, there was a standing ovation in Venice, and there’s a lot of beautiful responses to it. Sometimes people don’t understand it…

BOONE: Well, there are not a lot of painters that make movies. That’s why I’m fascinated by it.

SCHNABEL: I never knew that that’s what I was going to do either. I really did it because Jean-Michel [Basquiat] died and somebody was asking me about him and he wasn’t really listening, or he didn’t really understand. The problem with movies is people don’t know what their subject matter is. I know something about being an artist, and my experiences were similar to Jean-Michel’s experiences at that moment in time. And he died and I lived. I’m here and he is not, but his work is here. And when I’m not around, my work will be here too.

BOONE: It’s true. An artist always has their work as their legacy.

SCHNABEL: Well, you have this painting of Saint Francis of Assisi in Ecstasy in your house, so you get to see me every day.

BOONE: [Laughs] I know I do. Every day I say, “Hello, Julian.”

SCHNABEL: That’s one way of communicating with each other. Everything I had to say was in that painting.

BOONE: I remember when I first came to your studio and I saw that painting and I had to beg you to let me have it, because you didn’t want to sell it.

SCHNABEL: It was a good thing that I did acquiesce and that you have it. I’m happy that you do.

BOONE: I’m happy that I do too. It’s a grounding in my life.

SCHNABEL: We should show it somewhere soon. People should see that painting. It’s one of my favorites.

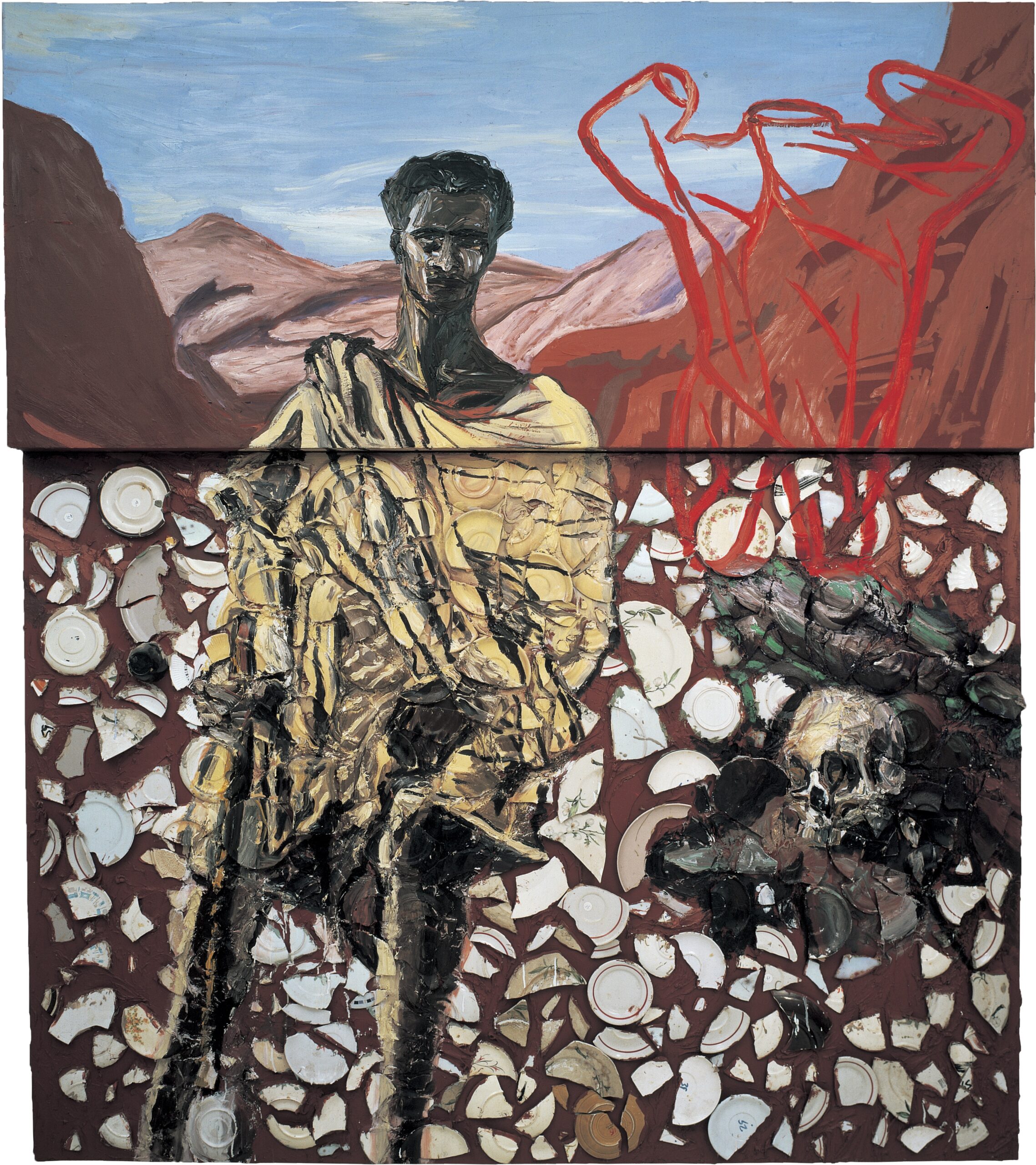

Julian Schnabel, Aborigine Painting, 1980. Oil, plates, and Bondo on wood and canvas. 96 × 86 inches (243.8 × 218.4 cm). On view at Lévy Gorvy Dayan: Downtown/Uptown: New York in the Eighties.

BOONE: We can show it. You know more about the art world than I do, being an artist.

SCHNABEL: I don’t know. I think there’s a difference between the art world and the world of art. And it’s shifted a lot from when we were kids. Or when we…

BOONE: When we started, we were kids.

SCHNABEL: When we were coming up, there were a lot of people that were vibrant and amazing to be around. John Chamberlain for one, and I spent a lot of time at Max’s Kansas City in 1974.

BOONE: I remember that.

SCHNABEL: I was the youngest person in the room at that time. Richard Serra, Robert Smithson, and obviously, Bob [Robert] Williamson were always around. But Frosty Myers had that sculpture cantilevered in the middle of the…

BOONE: I think it’s still there.

SCHNABEL: I haven’t been in there in a long time, but it was a very different time in the world. There were places where people congregated, so there was a sense of community.

BOONE: The thing is that all these young artists now don’t have a place to gather, like the Cedar Bar or Max’s Kansas City, or the Ocean Club. Even doing this on Zoom, it’s a different thing.

SCHNABEL: Sure. Obviously, we’re just talking now, but in general you need to see paintings in the flesh. You need to stand in front of them and let them do what they do or they don’t do to you.

BOONE: I loved your work from the first time I came to see it, but I was having trouble selling it. I got Klaus [Kertess] to come to your show, and he brought Patrick Lannan, and it was like love at first sight. He bought the painting, and it was a great one.

SCHNABEL: Giacomo Expelled from the Temple. It’s at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles.

BOONE: I know, he [Patrick Lannan] gave his whole collection away to institutions.

SCHNABEL: Actually, that painting fell off the wall and landed on Patrick Lannan when he was in bed one night, but he didn’t get hurt. Luckily, it wasn’t a plate painting, it was a wax painting. But Giacomo Expelled from the Temple, was in my studio in 1979, when Clyfford [Still] still came up to New York and he was having his show at the Met.

BOONE: I remember in 1990, I did the Clyfford Still show with his wife. It was amazing that we had access to people like that. It seems like the world’s not like that anymore, in terms of meeting older people.

SCHNABEL: He’s not here. And Richard Artschwager is not around. Lawrence Weiner is going to have a show tonight at Barbara Gladstone. I made a painting of him a couple weeks before Lawrence died and gave it to his wife, Alice [Zimmerman]. It’s in her kitchen. She’s cool. But he used to hang around at Max’s. There was a great community of people there. That was a line in the film Basquiat, where Gary Oldman says to Jeffrey Wright, “Good conversations, hard to find in this town.” But I’m not nostalgic at all for the ’80s. I don’t miss anything. It’s funny, looking back at Basquiat, it doesn’t even look like that in New York City anymore. The facade has changed, but the fact is that the works that were made at that time… They hold up pretty well. The thing is, you have to see paintings in person, and the world keeps turning. But there’s a lot of young people that have never seen the works of some of the artists in your show in the flesh.

The Patients and the Doctors, 1978 and Notre Dame, 1979, in the artist’s residence, New York, 2021. Photograph by Tom Powel Imaging. Courtesy of the artist.

BOONE: That’s how things have changed. We were the last generation before computers. I think we had a special place, a good fortune.

SCHNABEL: Well, there’s a lot to be said about the digital age in terms of being able to make things easier, like printing is easier than silkscreens. Also, it’s expanded the possibilities of what a painting could be. We have to separate between the idea of people becoming less human because of the computer, and people using it in a way that is humane and constructive. There’s a song by Donny Hathaway, “Someday We’ll All Be Free,” that goes, “Hang on to the world as it spins around. Just don’t let the spin get you down.” I think that’s important too. I was talking at the University of Houston to the graduate class in the art school there last May, and I said, “If somebody asks you what you’re doing and you say, ‘I don’t know,’ that’s a good answer.” The great thing about making a painting is you don’t have to know what you’re doing. You could discover it after you’ve done it, or in the process of doing it. And if somebody tells you an answer right away, they’re probably lying to you. When I’m painting, I become a part of everything that’s outside and inside of me, andI am okay with that. If I didn’t paint, I would go mad. It was like that then when we met, and it’s like that now.

BOONE: I remember when we first met; that was funny. I think it was Ross [Bleckner] that introduced us.

SCHNABEL: Well, I think I went over to Bykert Gallery, and you were behind the desk over there. I had seen you before when you were Klaus’s secretary.

BOONE: That was a great time. I was lucky to get that job.

SCHNABEL: He was very lucky. It’s a beautiful moment to think of. There were a lot of opportunities at that time to show work. When you’re young, you’re very excited and you have all these–in Spanish you would say, “Tengo ganas para hacerlo,” meaning, “I have a need to do this.” You want to show your stuff. You want people to know who you are.

BOONE: You want them to respect you.

SCHNABEL: In those days, I don’t think there was actually a lot of respect for young artists. I’m also thinking about the invisible days, the audience that you think are out there. But after a while, you have no idea who the audience is. That’s not why you make the art, but I think when we were younger, there were things that we were seeing at that time that were important for us to do. Like being a part of what was going on in Europe. We wanted to bring the world across. So, all of a sudden there was Francesco Clemente and Enzo Cucchi and Sandro Chia. And Georg Baselitz and Markus Lüpertz were much older, obviously. In 1974, Sigmar Polke came to New York, and he and I were pretty good friends. Blinky Palermo was my friend. But I hadn’t been to Europe at that point.

BOONE: I thought you had met Blinky Palermo and Polke when you were in Germany? I thought you were Polke’s student.

SCHNABEL: No, absolutely not. Sigmar Polke came to my studio in 1974 because he was visiting Ernst Mitzka in New York, who was going out with Marjorie Heidsieck, from Heidsieck Champagne. And he was friends with Blinky Palermo. I knew Blinky because Blinky used to go to Max’s. And he also used to go to Negril, and we would drink together over there. When Sigmar came, Ernst Mitzka introduced us. He came to my studio before I ever saw a painting of his. So, you got it a little backwards there, but that was okay.

BOONE: When we did his first show, which was like in ’83, he acted like he really knew you for a long time.

SCHNABEL: Well, he did for almost 10 years. When I finally did go to Germany, I stayed at his house in Mönchengladbach, and we had a lot of fun together. When he was in New York, he was… Well, he did a lot of crazy things. He’d go up to luncheonette windows, and he would lick them while people were sitting on the other side, eating breakfast. Or he would take his camera out and take a picture of the guy next to him on the train, which is illegal. He would wear these tiger skin pants and he had this really long hair that would be combed back. But he was very, very funny. He was also a really great artist. He’s one of the few artists that I really, really, love. Particularly these purple paintings that have these images printed on them, which are at the Dogana in Venice. He was using a lot of materials that I think probably made him sick ultimately.

BOONE: Sigmar?

Installation view of Downtown/Uptown: New York in the Eighties. Courtesy of Lévy Gorvy Dayan, photos by Elisabeth Bernstein.

SCHNABEL: But Blinky’s work obviously didn’t look anything like Sigmar’s work, but there was something that was pre-made in both, whether it was material that Sigmar found that he was painting on, or pieces of the Stoffbild paintings that Blinky made where he had things sewn together. And if you looked at a Barnett Newman painting, you think, “Well, why in the world would he do that? Didn’t it already get done?” But in fact, no, it hadn’t been done. We need to start looking at the way materials were being used, and people’s attitude towards distance.

BOONE: How far back you stand away from a painting, is that what you’re saying?

SCHNABEL: No. I’m talking about distance in terms of objectivity. Meaning if you look at Brice [Marden]’s paintings, you see the marks. Even if you see the palette knife, you see a meditative repetition of mark-making that’s happening. If you look at Blinky’s, you see a piece of material that’s sewn to another piece of material. Like Frank Stella said, “There’s only two things are how to paint and what to paint.” Frank Stella and I became very, very good friends later in life. I have this incredible painting in my house that he gave me. It’s gigantic and it’s really wild. I never get tired of looking at it. But I live with obviously the art of other people too. I have this great big, beautiful Andy Warhol portrait that he made of me that we had traded. The painting I made of him, a velvet one, is at the Hirshhorn. Then I have a Francesco Clemente that’s built into the wall of the library in my house here. Cy Twombly gave me some beautiful drawings.

BOONE: I saw those in your house. The drawings.

SCHNABEL: I was painting The Walk Home of plate painting that Eli Broad owns from 1982, and Cy was in my studio looking at these two drawings. They looked like garbage on the floor. He said, “Can I have those?” I said, “Yeah, sure.” “I’ll give you something someday from him.” But this was what you were talking about, Mary, this sense of community. Even older artists wanted to be part of this thing or felt like there was this community.

BOONE: Like Andy loved coming to our openings because he felt more accepted. He told me he felt more accepted by the young artists that I showed than he did by his own generation.

SCHNABEL: I think that Bruno Bischofberger introduced all of us to Andy over at Christ Cella. That was a great thing, to go and eat in the kitchen over there with Jean-Michel. There were also different factions in this group in the ’80s, obviously. I was friends with Jeff Koons. I think I was closer to Jeff than to some other people.

BOONE: Well, you introduced me to Jeff.

SCHNABEL: Well, I actually traded…I bought his old green Mercedes.

BOONE: The car.

SCHNABEL: Jeff gave me the car. What did I give him? I don’t remember anymore. I think I bought it.

BOONE: You got the car. Then you traded the car with Brice for…

SCHNABEL: Exactly. I got the car, and then I traded the car for two suicide drawings with Brice that I still have.

BOONE: I think his daughter still has that car.

Mary Boone and Julian Schnabel in 1980. Photo by Bob Kiss.

SCHNABEL: I remember early on when David Diao took us to his studio late one night, I commented, “The paintings aren’t done.” And Brice said, “Well, you’re a student, you don’t have the right to say anything.” And I said, “Well, we’re all students.” And then he got pissed off and tried to swing at me, and then we fell on the floor. I said, “I’ll let you go if you stop trying to hit me.” Forty years later, he asked me what I thought of a painting in his studio. And I said, “I guess I’m old enough to speak now.” I figure if you live long enough, you can laugh about those things. Obviously, we knew each other for a really long time, but I think we had a mutual admiration. Even though he was very tough on me when I first came to New York as a kid.

BOONE: Brice said to me that he always measured an artist’s worth or value by virtue of how much it integrated into your life. He said every time he’s driving on 6th Avenue, he sees the tarps on the side of the buildings that he thinks of Julian. And if he thinks of Julian, then it must mean that you’ve had a big effect on the world. He even said it in an interview I read recently.

SCHNABEL: That was nice that he said that. Anyway… It’s been nice talking to you, Mary.

BOONE: Nice to talk to you, Julian. We should do this every week.

SCHNABEL: We don’t have to have a recorder. We can just talk. I’ll see you again soon.