IN CONVERSATION

“Should We Talk About Death?”: P. Staff and Jamieson Webster Take Aspen Art Week

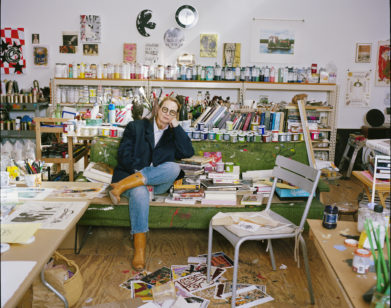

Photo by Emily Sandstrom.

TUESDAY 8:07 AM JULY 29, 2025 ASPEN

Early on a Tuesday morning, the psychoanalyst Jamieson Webster and the performance artist P. Staff gathered in the dimly lit Aspen Chapel for a conversation that turned out to be rich with analysis and alive with chemistry and insight. Coming from two different disciplines, they found a natural common ground discussing their respective practices, suicidal patients, Freud, Ferenczi, and the very notion of “final words,” all at the bleary hour of eight in the morning. Their exchange echoed through the rest of Aspen Art Week, leaving many to contemplate their ideas as they took in other fairs, dialogues, and exhibits.

Their conversation kicked off the inaugural AIR Festival, hosted last week by the Aspen Art Museum, where a chunk of the art world banded together for a packed lineup of performances, keynotes, and conversations. The 10-year initiative was made possible by a $20 million donation to the museum, supplied by a number of sizable foundations and deep-pocketed art enthusiasts. After a few hours of stomach-lurching turbulence over the Rockies, I was thrust into the festivities: Paul Chan in conversation with his AI self; Werner Herzog dissecting alien gang-rape in conversation with Hans Ulrich Obrist; a titillating and intricate installation by Mimi Park tucked away in the Aspen Physics library; a refreshingly candid conversation between two institutional legends, Glenn Ligon and Thelma Golden; and a breathtaking 90-minute performance piece by Matthew Barney, which strung together huskies, horses, cowboys, a hula-hooping professional, an assault rifle, two marching bands, and two quarterbacks on a remote cattle ranch—offered as a commentary on structural violence in American football.

Having successfully cajoled art stars from across the world to pad out an undeniably strong program, the question rang loudly throughout the course of the week: Could a steep $20 million dollar cash infusion confer on Aspen the kind of art world cultural relevance typically reserved for coastal cities? Between sucking down oxygen canisters to support my adjustment to the altitude and taking in Herzog’s fevered imagination, it certainly seemed so. Fortunately for us, we got the exclusive on Staff and Webster’s haunting and intimate conversation, an abridged version of which appears below.

———

P. STAFF: Good morning. Thank you for that incredible performance.

JAMIESON WEBSTER: Good morning. I’m so happy to be on air, and I’m so happy to open this day.

STAFF: When we were walking yesterday, I mentioned that maybe what I would call volatile in psychoanalysis and in your work, you would call disorder or disorganization. Does that feel accurate?

WEBSTER: It feels accurate. I wrote a book called Conversion Disorder, and then I have a collection called Disorganization & Sex. I really love these two words. Conversion Disorder is actually the term that came to replace hysteria when the Diagnostic and Statistics Manual in Psychiatry wanted to get rid of Freud. And I thought, “What a wonderful term.” The idea is that the conversion is the volatile conversion of psychic life into bodily symptoms. Then I thought, “How can this be a disorder?” Or, “This is all our disorder.” The next book, in terms of disorganization, brought forward the question: “How hard is it to make room for disorganized states of mind?” So many of the ideas around mental fitness and wellness is that you’re going to get yourself organized and you’re going to get yourself grounded. And actually, what psychoanalysis does is really the opposite of that. I also think about art that way as well.

STAFF: Is the nightmare disorganized dreaming, or is all dreaming disordered? Because there is a value judgment in there. If I had a dream last night or I had a nightmare last night. Is one more ordered than the other?

WEBSTER: Well, Freud said that the nightmare is a failed dream. And the reason was because a dream is supposed to keep you asleep. If too much anxiety creeps in and you wake up, then the dream has failed. Part of what you’re doing when you’re dreaming is you’re wishing. And if the wish makes you anxious, then you fail to sleep. The French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan said that the nightmare is the real dream, because we don’t want to wake up. We don’t want to enter back into reality. The nightmare shows you what you are terrified of, what you are afraid to want for yourself. He was very worried that we wouldn’t wake up, and Freud was worried that we wouldn’t dream. They’re very funny parallel figures in that way.

STAFF: I remember in your book about breathing, there are these incredible passages about the nightmare being a process of turning things inside out. Am I remembering that correctly?

WEBSTER: Yeah. I said that the importance of the nightmare is actually to find what’s tender in it. The importance of the wishful dream is to find out what’s terrifying and anxious in it, so you’re in this process of turning something inside out. But also, a lot of your work deals with the question of whether you want to look away from what wants to penetrate and get inside something. A big part of the breathing book is this theory by a psychoanalyst named Sándor Ferenczi, who believed that we all wanted to go back to the sea—because in the sea, everything was fluid. It was nurturing. We are in an environment that can support our body weight, and the things that need to mix, mix outside of us. He says that the catastrophe is that when the seas dried up, we went on to land and we were forced to evolve and into whatever human beings are at this point in time. And that fluidness became the question of the fluid needing to be inside the body in order to protect the embryo, so we developed sex and we developed death and we developed penetration. And that when the baby is born, the seas again crash the child onto the shores, and we have to redo that entire ecological catastrophe. It’s a wild theory.

STAFF: It’s incredible, this idea that we all relive this trauma in the moment of birth, and that we then spend our lives essentially rubbing our dry genitals to try and get back to this fluid state. I started ruining dinner parties by trying to tell everyone about that section in your book.

WEBSTER: [Laughs] Penetration, it’s really a figure for Ferenczi of needing to put something somewhere. To get something inside in order to protect it as a response to the catastrophe of life on land. There’s something in your work, where you’re thrusting upon the person that we cannot get outside of this desire. We have to see how we are trying to turn things inside out, and is there a less violent way of doing that?

STAFF: I would say no.

WEBSTER: I know you would say no.

STAFF: [Laughs] Yeah.

WEBSTER: Should we talk about death?

STAFF: I was about to say, I don’t know how to segue into death. It feels like a heavy thing to talk about this time in the morning. I wonder, curatorially, if you and I were put together because both of us have a certain high tolerance for talking about death, and also maybe a certain bluntness.

WEBSTER: That’s true. I think the most important moments in my work—and I know that you must have a strong relationship to this as a death doula—is what it means to be present for the people grieving and for the person who’s confronting death. In the book, I reflected on the fact that I’m going to go to the scene of death and I’m going to figure out how to make use of myself there, which has always been what psychoanalysis wants to do. It wants to go to the place where people are suffering and where the machinery of the world might just want to put a lid on it and to try to do your best not to let that happen. I wanted to be in the ICU with the patients who were intubated. I was very curious about intubated patients and the family members who had to say goodbye. But I realized at a certain point that this was to get away from the people who were dying but conscious. My own denial, delusion that there I am in the moment, is this courageous confrontation with death. I am, as anybody else, trying to do my best to get away from the question of what it means to be dying. I think you made very important statements about the difference between death and dying. Death, we don’t know. Dying, we have experienced to different degrees, or even had the idea that we are all dying. To live is to be in the process of dying and this is what’s very difficult to tolerate.

STAFF: Just to give a little biographical information, my entry into this world begins in childhood. Both of my parents work in assisted living facilities. I found it deeply unremarkable most of my life. I say that because it just simply was the job that my parents had. I would say that neither of them consider it a career. Neither of them consider it a calling or a vocation. It was paid labor and it was available labor. I didn’t reflect so deeply on this until the art world took a turn towards care. Suddenly, my peers were—not to complain about my peers—but extolling the virtues of care, being as audacious to claim that care is the antidote to violence. I sort of started to feel like I was going crazy, partly because anyone that’s spent any time around structured institutionalized care will recognize that a huge amount of violence happens in care. That care homes, assisted living, hospices are rife with violence, and that there is a constant tribunal addressing of violence. We are trained that most people do not want to talk about death, let alone their own death. Most people do not want to address the fact they’re dying even as they are actively dying. And one of the ways to coax this out of people was to talk about their values around dying. Do you value a quick death? Do you value dying at home? Do you want to be surrounded by your loved ones or do you want to be listening to music and in your own world? Often, many of us are comfortable talking about this value of dying rather than really confronting the reality of our own process of dying. Something that came up for me very early was that I just found myself saying, “I don’t want to die in a mass death. I don’t want to die in a plane crash, in a pandemic, in a shooting.” But in that moment I was like, “What the fuck am I talking about? How many people die every minute, every day?” And yet, I’m attached to this idea that mine will be the only one that day? It’ll be my death? It’ll be the most special one that’s ever happened?

WEBSTER: I don’t want to be one number amongst many.

STAFF: Yeah, exactly.

WEBSTER: This was this amazing point by Luce Irigaray, the feminist philosopher, when she was thinking about air-atmosphere interdependency. She was in this field of male philosophers for whom the existential question of my death was the most important aspect of philosophy. She said, “No, you’ve forgotten togetherness. You’ve forgotten our dependency on air. And whatever death is, it’s a death in common. It’s not my death.”

STAFF: Right, and maybe my umbrage with the emergence of death doula as a discipline—

WEBSTER: Is individualism.

STAFF: Yeah, there are these drives to professionalize, to privatize, to create yet another industry around death when, in fact, the reason that many of us end up gravitating towards end of life care is to understand that actually we need to alleviate the burden of privatized structured violence around the death industry.

WEBSTER: This was the hardest thought according to Freud, that we are simply a link in a chain serving the ends of our species that we will never know. It becomes the idea that the way in which you are part of a process of evolution whose end you will never see is one of the most radical narcissistic blows to the human being. I think about technology, where if we could catch up with where this technology has taken us, we will not see it. This is really an impossible thought, that you don’t get to see the end of what you were a part of.

STAFF: Something that really struck me in your book, Jamieson, was this phrase that the patient must want to live. Another part of hospice training is that often the living, particularly a family member or partner, might want to intervene in the dying process, often to try and prolong life. Of course, it’s completely understandable and natural. I made a work in the pandemic called Heaven that was about many of my friends expressing a desire to die and trying to stop myself from immediately saying, “No, you have to live.” How do you meet someone in a moment and say, “Okay, you want to die?” How does that emerge in your work?

WEBSTER: Two things come to mind. I think the hardest work I did with a patient was with someone who was trying to plan her suicide. I was scared, but every session felt like I had bought a day or two until the next time I saw her. I kept saying to myself, “I have to call the lawyer.” But I knew that if I called the lawyer, the lawyer would tell me that I have to do something, that I have to put her in the hospital, and I would ruin the treatment at that moment. I might save her life, but I would ruin the treatment. The treatment was keeping her alive, so it was an incredible double bind. I just had the thought to keep going, so I did for six months and we made it through the crisis. You have to see if you make it through the crisis. If you try to stop it prematurely, then you put the person in an endless cycle, which is what we also do with certain people who are having a psychotic breakdown and then we medicate them. You have to be really strong as an analyst, I think, and you have to really believe in the work, and you have to believe in your capacity to know the moment that you need to intervene—not by what’s told to you in terms of what’s going to keep you legally protected, or so you’ve crossed your T’s and dotted your I’s or whatever. The second thing is, just to go back to dreaming, the idea of making room for something like dreams is also making room for something like death. We all don’t want to go to sleep in some way, because it is a bit like removing yourself from conscious, rational, ordered, agentic life.

STAFF: When I began to seriously engage with death I thought, “Okay, this is an antonym to power. By living with death, by trying to be ready for death, I might begin to be able to relinquish this addiction to power that we all have, and my investments in living would change.” This sounds hokey. Suddenly, I feel like I’m giving a TED talk. It’s a complex kind of psychological process.

WEBSTER: A friend of mine made a joke about how excited we are about the trace of water on Mars, just to go back to our main theme. She said, “But there’s so much water here.” I think about this. Also, this ecstatic excitement for ChatGPT, OpenAI, large language models, that this thing produces this language back at us like that. I think we still don’t even know how to talk to each other. I think what you’re talking about in terms of trying to get away from mastery and power and acquisition is also very important, because power right now is information, and these are information machines. We go down this hole of wanting more and more and more information, and to what end? Living together, dying together is so difficult and you want to pad it with information?

STAFF: Something that I find hugely overblown is the idea of someone’s final words, that it’s quoted in history. You can look up a Wikipedia page and see someone’s final words as if it’s something we should all practice in our lives and decide what our last sentence is going to be. The experience in hospice care is that it’s not really about language at all. Final words might happen a long time before the passing, and the final words, if such a thing exists, usually have already transcended this immediate realm that we’re in.

WEBSTER: I remember this piece by the feminist performance artist Vanessa Place, where she went through the archive of last words, which they are forced to record for people who are facing death sentences. They have a microphone there, and they force you. You don’t have to say anything, but it has to be there for legal reasons. But what a lot of them say are just descriptions of the feelings of their bodies, which is really, really painful to listen to. Actually, it was surprising and it made me think of your work, because often at the end of your videos, you’ll enter into language after this intense experience with visuals and colors and the sounds. You bring a moment of language at the end. It’s not exactly last words because, again, it’s a description often of automatic forces.

STAFF: I’m having an overwhelming urge to be like, “Can we end on last words?” Can we end on the finality of speech?

WEBSTER: Yes.

STAFF: Do you have any final words, Jamieson?

WEBSTER: No. Thank you, everybody.

STAFF: Thank you for having us.