IN CONVERSATION

“It’s All Fear, No?”: Lena Henke, in Conversation With Urs Fischer

Lena Henke, photographed in her exhibition Good Year at MARTa Museum, Herford, 2023. © Gunnar Meier.

Spread across three floors of the Aspen Art Museum are John Chamberlain’s infamous sculptures of scrap car parts, deconstructed, crushed, and twisted. The man in charge of interpreting and contextualizing Chamberlain’s body of work is none other than the visual artist and sculptor Urs Fischer. “It almost sounds a little Christian, but don’t do to others what you don’t want to be done to yourself,” he jokes as he explained to Lena Henke his curatorial philosophy when approaching a new show of Chamberlain’s works, THE TIGHTER THEY’RE WOUND, THE HARDER THEY UNRAVEL. Henke, the fellow sculptor, photographer, and visual artist, opened her own show, You and your vim, on the same day, right overhead on the museum’s rooftop. Henke’s exhibition tackles her long-standing fascination with figure and environment and features a soaring bronze figure of a woman and an oversized mirror that reflect visitors legs back to them as they explore. Once they returned home from Aspen, the two artists got on Zoom to discuss Chamberlain’s legacy, how their tastes have changed with age, and the solitary nature of art-making.—EMILY SANDSTROM

———

LENA HENKE: Good to see you. Did you get back okay from Aspen?

URS FISCHER: Yeah. I caught a cold, but the rest is good.

HENKE: Oh my God, I got sick, too. I had a 15-hour flight back and arrived here and my baby is sick. I’m going from one extreme to the other, from the mountain ski resort, very exclusive, back to cab work.

FISCHER: It’s always an interesting contrast. On one hand, you change diapers and the evening before you had opening.

HENKE: I know, yes. I never thought that would happen, but here we are and I quite like it. I wanted to say, and maybe this sounds cheesy, but you really put fresh blood into [John] Chamberlain for me. I think it was the best show of Chamberlain works I’ve ever seen. I think it’s an epic, epic show. When I had my long flight back, I looked through the catalog and I thought about how important it is for you to curate, because you have been doing it since you started your career, right, basically 30 years ago?

FISCHER: It’s similar to looking at works by others. You can learn for yourself, for your own practice. It’s interesting to try to understand what the whole thing is actually about. Not that you will ever have a conclusive answer, it’s an ever-unfolding journey to me. When I was young, I was pretty opinionated about what’s good and bad. But this order starts to disintegrate and you start to appreciate or see other things. I used to have a practice where I looked at works of artists I never liked.

HENKE: That’s good, because you want to try to understand them.

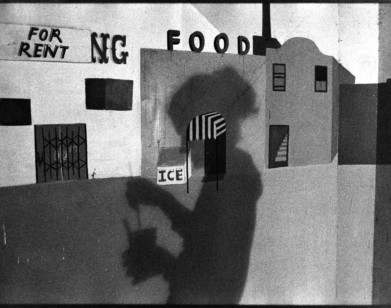

John Chamberlain: THE TIGHTER THEY’RE WOUND THE HARDER THEY UNRAVEL, installation view. Courtesy of the Aspen Art Museum. Photo by Daniel Pérez.

FISCHER: Even things that are only 10 years old already look kind of irrelevant and stupid to you. I remember one of the first people I looked at was [Marc] Chagall. I never understood Chagall. Up in Zurich, they have this Chagall window, Chagall this, Chagall that. I just never understood. It always felt kitschy or something. But when you get into it, it’s very beautiful. You allow yourself to explore a bit about what it is rather than the the parameters you prop up for yourself. To curate the show with Tony Shafrazi was very different. That was much more about a sampler platter of a mythology of the New York art world. The works were well really chosen, but it was more about a story. The difference was that I was never tasked with the responsibility of working with another artist that is not alive anymore, you know?

HENKE: Yes.

FISCHER: An institution always has an educational thing. It’s not an experimental ground. You go there and you want to get a full menu. Going to a museum is almost like going to a banquet. You get the starter and you get the main dish and then you get the dessert. There is a kind of an order to that. It almost sounds a little Christian, but don’t do to others what you don’t want to be done to yourself. [Laughs] It’s about trying to make somebody’s work look as good as possible.

John Chamberlain: THE TIGHTER THEY’RE WOUND THE HARDER THEY UNRAVEL, installation view. Courtesy of the Aspen Art Museum. Photo by Daniel Pérez.

HENKE: Absolutely, that’s why I like to switch it. I started curating shows when I came to New York, 2011 or 2012, after the crash. Money came back in and I was so disappointed with the New York art scene, especially very easy, sellable works in shows. I was pretty bored. So I started curating these shows with a friend of mine with no budget at all, and we used the city as a backdrop. The first show was called Under the BQE [Brooklyn Queens Expressway]. And you know what I liked the most? The install and the de-install, because we had 20 artists, super young kids, but we also had well-known artists. This energy they had created, that was the best for me. I love that so much.

FISCHER: Yes, there is the communal aspect, too, the installation or working with people. I mean, I don’t particularly like making art as a practice because I like people.

HENKE: I get that from you.

FISCHER: A lot of what we do, we do alone. For a painter, you just lock yourself in your studio for 10 hours.

HENKE: Tell me about it.

FISCHER: I don’t do anything if I don’t think there is a need for it or a place for it. I don’t have a way to relax in my work, in a way. Because I like the communal part, the most fun I ever had with art was when I did this project Yes at the Geffen [Contemporary MOCA]. We had between 30 to 200 people everyday. All the divisions fell down and everybody had so much fun because you’re just doing something together. I’m a firm believer in synergy. Synergy is the key to anything.

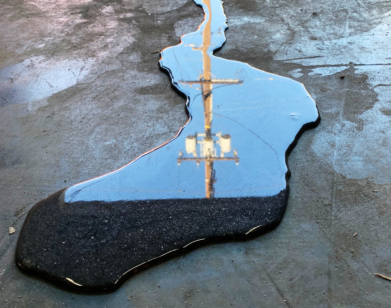

Lena Henke: You and your vim, installation view. Courtesy of the Aspen Art Museum. Photo by Daniel Pérez.

HENKE: Looking more into your work now, before Aspen, I realized now what it brings you, working with the community. When I saw your piece where you invite the public to come in and change the work, I didn’t get that. I was like, “Why?” I remember that piece on the Lower East Side, at JTT, right?

FISCHER: Oh, yeah.

HENKE: But now seeing the Geffen work, I really understand what you get out of it and I find it very impressive.

FISCHER: Well, there are two different things. One is the communal energy, as we said. The other is more a proposition. You have this work by [Aristide] Maillol, which I really always was a bit creeped out by. Most of his figures look like they’re a little too young, you know? Then at the very end of his life and as Europe slides into turmoil, he makes this fully mature woman that is kind of falling. It’s such a strong sculpture. To have this kind of figure that’s already distressed invites people to interact. We as humans are pretty strange when somebody shows weakness. You can respond in various ways. One is to care and to protect. Then what often happens is the insecurity throws people off, so some people do something nice with it and for other people it brings out aggression. They want to rip off an arm. You know, you could at any point repair the work as much as you could rip it apart. People like to tear things apart, and once things are a bit torn, they tear more and more. It’s like what we do to the planet.

Lena Henke: You and your vim, installation view. Courtesy of the Aspen Art Museum. Photo by Daniel Pérez.

HENKE: True, yes. It’s so interesting because the moment of fear pops up in several interviews with you. I looked back at the first interview you did with Interview with Gavin [Brown] in 2008, and he asked you that fear question: “Are you afraid of something?” I had this sentimental moment on the airplane as I was watching a movie and there was this quote by a monk that goes, “You should live neither in fear nor hope.” I was thinking maybe you would like that.

FISCHER: Yes. [Laughs] Try to have children and not live in a monastery. But fear is always interesting. I mean, it’s all fear. No?You are at the mercy of your fear. Your fears go so deep, sometimes you don’t understand what they are. Like this morning I woke up and I had this dream. It was just a simple image, I fell to the floor and I was holding some things and then came this big dog. I am usually afraid of dogs, but I was not showing that I was afraid of the dog. Then the dog became kind of just a big dog, and it was good. [Laughs]

HENKE: That’s funny because I had a dream last week when I was reading so much about you, where I made a clay piece with you. I think it has to do with the fact that in 2018, when I prepared my show at the Kunsthalle in Zurich with Daniel Baumann, I was in awe going there because they have this archive of over 3,000 materials and you feel like an alcoholic in a wine shop. That’s where I saw your clay models. I was thinking about scale a lot and how I always need a reason or a concept in my work to relate to scale. When did you start working so large? What is your perfect scale? And how do you scale them up, the stamp clay pieces?

FISCHER: I don’t know. You do the same in your work. You think a lot in space, no?

HENKE: Yes.

FISCHER: I mean, we’ve been tossed into a world with a lot of large exhibition spaces. So, logically, we all respond to it, and the work gets bigger on average across the board. Some things just make sense when you’re in a spatial scenario. There is a physical scale, but there are also emotional scales. Sometimes, if you have a simpler image, maybe that contains itself, there are broken images that are kind of fractured where you move through.

HENKE: You said, “3D is reality somewhere.” I like that.

FISCHER: In a way, when you make a sculpture, you compete with the physical space. You don’t produce a two-dimensional image, but you can enter and see at any scale from a thumbnail, like a big cinematic projection in a way where you kind of engage into a dream. There’s not much dream in sculpture, as you know.

HENKE: That’s true. There’s a lot of dreams in the current book [John Chamberlain Against the World]. I was wondering if you could ever see these juxtapositions between Chamberlain and all the artists you put him together with from the past 100 years or so? Although I read in the book, Chamberlain preferred to be shown alone.

FISCHER: Yeah, that’s how it started with this book. A person like him, to me, being born 50 years later, always seemed kind of cool but old. [Laughs] Maybe it’s more of a visual formal orchestral concept that you kind of can communicate with on that level. But other than that, it is a part of history in a way, you know? So out of this came the idea, we juxtapose it with other artists. Some of them small, large, it could be an image, it could be a physical thing. A big problem we will all see unfolding more and more is the cost of putting on any institutional show. Like, a lot of the big retrospectives you have in museums will disappear entirely, like the Rothko show that was in Paris. That’s probably the last time someone could afford all of the insurance values to bring all of these works together.

HENKE: Absolutely.

John Chamberlain: THE TIGHTER THEY’RE WOUND THE HARDER THEY UNRAVEL, installation view. Courtesy of the Aspen Art Museum. Photo by Daniel Pérez.

FISCHER: When I grew up, not even that long ago, there were provincial museums that had a Van Gogh show or a Dali show, or whatever. These kinds of shows disappeared because of the costs. The cost of transport, insurance, the values, nobody wants to lend them. I realized pretty soon that’s a really uneconomical way of bringing a new context to Chamberlain’s work. Each thing would come with a courier and a fee or you will not get the good work. In the photo you get the best one. So, digitally is even easier, but the liberty of how you can send and juxtapose and share images, that’s what I love about books, still. I’m antiquated this way.

HENKE: And the book is free, which is a really cool move. Instead of shipping another Chamberlain work, you decided to print out the book and give it away.

FISCHER: I mean, I know you made books in the past.

HANKE: Yes, I made many books.

FISCHER: You gave me one manual that looks so beautiful, so you know how much time it takes to put that together.

HANKE: Absolutely. I wanted to take one last turn. I was thinking about cigarette boxes because my favorite room of your Chamberlain show is the foam room, the second room of the show. The foam works, especially the models, they’re so beautiful and inspiring. Can you talk a little bit about your idea about putting the foam works in the front and then you end with these two boxes?

FISCHER: Yes. I’ll give you a bit of context. He started using car parts in 57’, 58’, and then he thinks, “I’m going to move onto the next thing,” because, you know, you have endless new ways in front of you. I had two theories about the foam. One is, I think he started carving his couches and the foam is a lot of garbage, so he would probably tie it together. [Laughs] That’s a personal theory. And then the ducts, if you think in the context of the mid-sixties and him not being part of a minimalist movement, there is more of an honesty of materials, you leave things be. You don’t have a decorated sculpture, a painted sculpture, like a [Alexander] Calder, you don’t have a bronze cast. You use the raw thing. This is very different from the car parts, because they already have a story inherent in terms of their shape, their paint, and then the force he applied to that. But these things, the duct and the foam, they’re kind of just raw materials where he kind of left his not very refined mark. One is just tied together and the other one was crushed at the place around the corner from his house. So he bought these ducts and they were just crushed together.

HENKE: I heard many rumors about the ducts. Some of them are from [Donald] Judd, who was a big fan of his work and tried to understand Chamberlain. He had some leftovers. That’s a rumor, right?

FISCHER: Could be, I don’t know. But they’re industrial products. They were new at the time they were crushed, just left bare, unpainted. In that room, it’s all simple action taken to some raw thing. And funny enough, the raw thing travels through time and takes on a lot of patina, which gives it his history. Not dissimilar to the car paint, but the patina brings in the history to the action.

HENKE: Another rumor is that he would always crumble the cigarette boxes at Max’s Kansas City. And then I read about your very minimalistic booth with Gavin [Brown’s Enterprise], where you just showed a crumbled cigarette box in the booth?

FISCHER: Yeah, well it had some mechanisms, so it started to move around and then, at times was like flying off and then landing and moving.

HENKE: Nice. Should we leave it at this?

FISCHER: Yes, thank you.

HENKE: Thank you.