OPENING

“She’s a Real 20th Century Figure”: Thelma Golden on the ICA’s Mavis Pusey Retrospective

Hallie Ringle and Thelma Golden. Photo by Emma Schartz.

Mavis Pusey knew what she wanted: communion with nature, a vibrant social life alongside fellow artists, and to finally overcome her fear of driving at night. She also wanted to build her own world of ideas through artmaking and, in her own words, “$1,000,000 from unexpected sources.” All of this comes through in Mavis Pusey: Mobile Images, the Institute of Contemporary Art Philadelphia’s latest exhibition, co-organized with the Studio Museum in Harlem. Walking through two floors of Pusey’s paintings and archival materials, this desire infiltrates the architecture, providing the fuel for her prodigious output, much of which ultimately fell into obscurity.

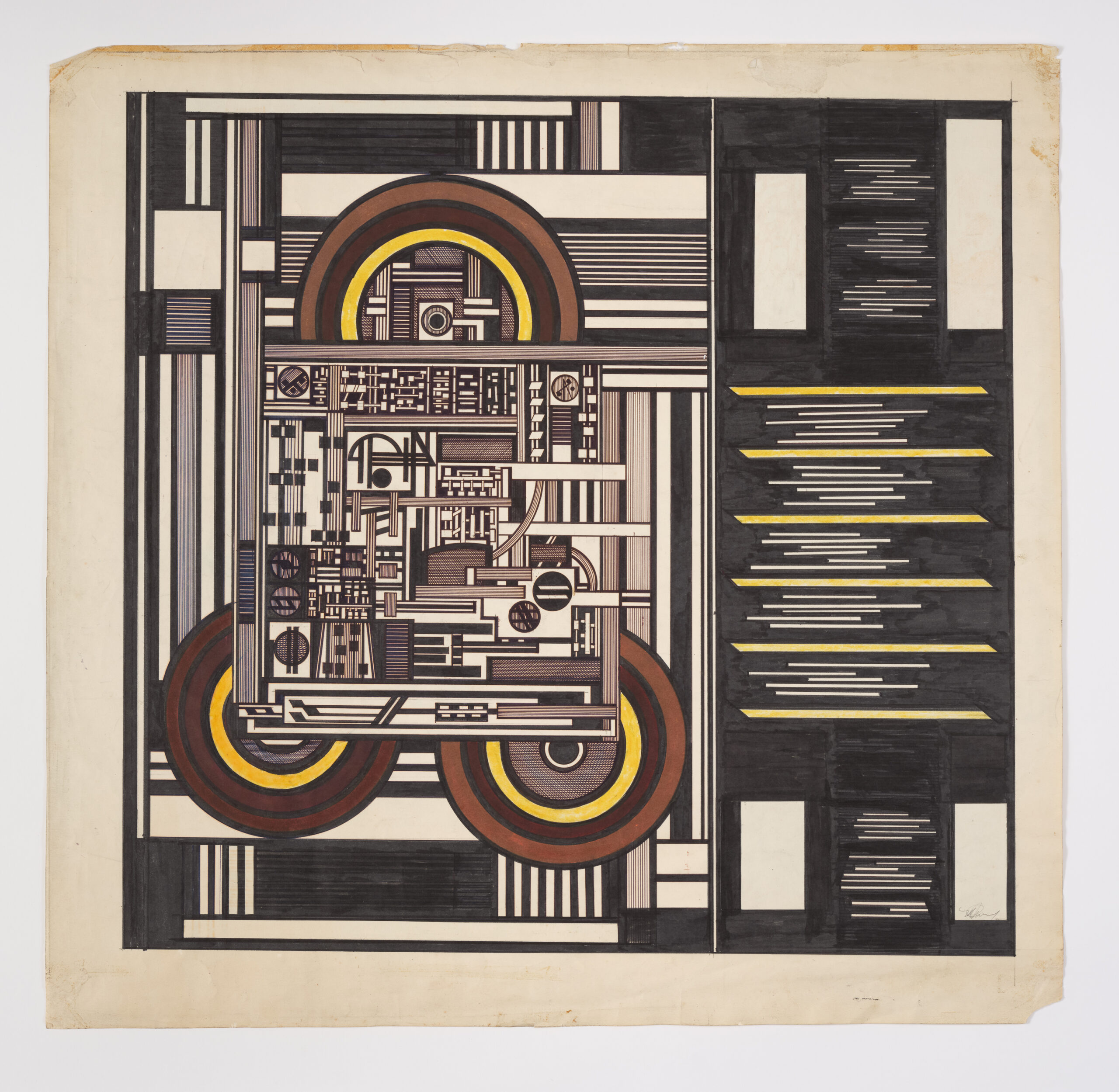

Across massive canvases and hard-edge prints, Pusey translated the clamor of urban construction and gentrification into fractured planes, sharp diagonals, and rhythmic blocks of color. Buildings stretch and collapse; cities thrum in gridded hues of rust, ochre, and deep cobalt blue. In one painting titled “Within Manhattan,” overlapping rectangles seem to vibrate in place. Her compositions usher the dust particles of 1970s New York into lines, gesturing toward both the past and future. Born in 1928, Pusey arrived in New York at 18 and would spend the next several decades moving from the Art Students League to Robert Blackburn’s printmaking workshop to exhibitions in Paris and London, culminating with a landmark showing in the Whitney Museum’s Contemporary Black Artists in America exhibition in 1971. “She’s a real 20th-century figure,” says Thelma Golden, director of the Studio Museum, whose discovery of Pusey’s work in an auction catalogue sparked the collaboration. “You feel the way in which she not only envisioned an artistic path for herself, but a place in the world.” Ahead of the show’s opening last week, I spoke to Golden and curator Hallie Ringle about the decade-long process that led to Mobile Images, Pusey’s bathtub garden, and what the artist’s work reveals about timeless ambition.

———

EMMA SCHARTZ: We can start by talking about how both of you, as curators, have approached this incredible exhibition. You’ve both worked to recover and elevate voices that are not typically accessible or well-known within the art history canon. Working on this exhibition, were there any specific paintings or pieces from Mavis’ archive that served as an entry point?

THELMA GOLDEN: Our mission at the Studio Museum in Harlem from our founding has been to create space for the voice and vision of Black artists, and that’s animated me over my career. That is to say, I am always learning. So about 10 years ago, I was looking at an online auction catalog and I saw some abstract works, some geometric abstraction. It was a sale of works of African American artists, and while they looked familiar, I didn’t know them. The language of the work fit within an aesthetic lineage that I understood, but I didn’t know the artist. I will say that my first inquiry was ego-driven. It was sort of like, “Why don’t I know who this is?!” But that is often the question that I encounter, because my work has a lot to do with what it means to have the voices and visions of so many artists, particularly artists of African descent, that are unknown. So I did what one does when you’re a museum director who’s not a curator: I asked a brilliant, tenacious, engaged, committed curatorial voice. I probably put a Post-it with my very bad handwriting on it saying, “I want to know more,” and that’s where Hallie comes into the story.

HALLIE RINGLE: That’s exactly where I came in. There was a website like mavispusey.com, where I got to see a bit more of her work, and there were these amazing prints that were very clearly influenced by music, because they had these musical staffs in them. And you could see, even in these pictures of them, that she had layered color. So it wasn’t just purple, it was purple under black, or it was orange under black. Then thinking about her as a person that really had quite a global influence got me really excited about her practice. From that point on, I learned so much global history just from Mavis alone.

Photo by Emma Schartz.

GOLDEN: But very practically speaking, handing the Post-it with the question mark led her to research Mavis, not only those works she saw on the website, but to try and chart a course and understand where Mavis fit. That’s what made us feel that there was some potential there. I don’t know if we would’ve called it an exhibition yet, but research potential. For many curators, research can be the work in and of itself, and it doesn’t always end up in an exhibition. Sometimes that research can just become a new body of knowledge that maybe gets tucked away for years. But in this particular case, it became clear early on that there was the potential to create something that would be public.

SCHARTZ: Absolutely. Hallie, I know you’ve been working on this for nearly a decade. What do you feel sustained you throughout this whole practice?

RINGLE: In a lot of ways, it’s easy with an artist like Mavis because her work was so expansive and had so many touch points in the world. I mean, it was also made easier because I had support from the Studio Museum and the Warhol Foundation. But to be able to pick apart the different threads of Mavis’ life led me down some very interesting paths. Thinking about her time in London to her role in May 1968 and how that led her to music and to the Atelier Populaire and its resonance today. Then to also be able to spend time in Jamaica and connect with the National Gallery there and think about what her formative years looked like. Also, to really spend time with her archival material and realize that she was in touch with Mohamed Melehi, the geometric abstractionist who was formative in the Casablanca School. And on top of that, her time in New York and at the [Robert] Blackburn Workshop. There’s a whole lifetime of research that could go into a person who was as dynamic as Mavis.

GOLDEN: She’s a real 20th century figure. So much of the trajectory of her life as well as her art and the aesthetic dialogues they’re a part of are so emblematic. For me, what is important about this project is not only Hallie’s ability to create a narrative that allows us to take a path through Mavis Pusey’s work, but also the ways in which this path will create recognition for how her ideas have animated contemporary art.

Untitled, n.d. Ink and graphite on paper. Private collection.

SCHARTZ: Absolutely. In preparing for this interview, I listened to a 1981 lecture that Mavis was giving in Maryland. And not only does she talk about working with Robert Blackburn and Romare Bearden, but she really talks about that urban movement a lot. I was wondering if that is really integrated into the exhibition, how Mavis moved around a lot?

RINGLE: A hundred percent. We haven’t shied away from any facts of her life in the exhibition, which is that she was at the Art Students League. She was on a student visa and her visa ran out. An immigration official showed up at her door and told her she had three months to leave. So she went to London to live with her brothers and she worked as a pattern maker. She printed with Birgit Skiöld, and that took her to Paris. We have an entire section about her time in London, and a section on her fashion. The archival section is curated by Kiki Teshome from Studio Museum, who’s done a wonderful job of building out these stories to show that she really had a lot of agency in the way that things played out. She was with her brother, but she was also connecting in different places to artist communities, and she was building worlds around her. She saved a lot of archival material from Paris, and that’s where we find the first examples of her screen prints. The Atelier Populaire was teaching people how to screen print. There’s no direct evidence that that’s where she learned, but she does talk about screen printing at her home.

Paris, Mars – Juin, 1968. Screenprint, 33 x 24 1/2 inches, full margins. Private collection.

SCHARTZ: That’s incredible. I feel like a big part of this story is also that her archive is fragmented. It seems like an important part of the work that you guys wanted to do was bringing it all back together. How did you navigate silences or absences in the story?

GOLDEN: Some of the gaps that might be in the material now will get filled in. This project becomes part of that larger archival process, and more will come from this period. I also think about exhibitions as being part of what creates the impetus for not just the use of archives, but also for their continuing growth as more people engage with an artist’s life.

SCHARTZ: It’s never-ending. What did Mavis’s New York City feel like to both of you as you were approaching her work and going through all of these years that she spent in this city?

Installation View of Within Manhattan. n.d. Oil on canvas, 73 x 96 inches. Private collection. Institute of Contemporary Art, University of Pennsylvania. Photographed by Constance Mensch.

GOLDEN: Well, in an early encounter with her work, my assumption of her put her in the middle of a deep, profoundly important community of artists, many of whom were deeply involved with the Studio Museum. So I have all kinds of questions about when she would have been in the museum? Knowing her connection to many of the artists who also printed at Bob Blackburn’s workshop, including someone like a Romare Bearden, who then also was deeply involved with so many other structures, organizations, institutions. Then the Arts Students League, thinking about the intersection of artists who studied and taught there, and knowing that so many of these artists were socially and professionally connected. They had deep engagements with each other. Some of us who were lucky enough to work at times when many of them were still alive, to understand how fertile and how rich those moments were when they were making and creating and engaging in such deep ways.

RINGLE: She did also contribute to a Studio Museum benefit at some point. But I think New York to Mavis is exactly how she describes it, a city of hope and of movement, of past and present simultaneously. This is a person who saw the history and the possibility in every corner and in every brick. That’s something that I’ve always loved about her work, how it feels like it could be made today or 50 or 60 years ago. We found some photographs that will be in the exhibition, and you can really see the city through her eyes. It’s incredible to see how truly everything was geometric to her. She says that in some of her lectures, but I couldn’t really see it until I saw the photographs. And once we saw the photographs I thought, “Oh, yes, this is it. This is her life. This is her world.”

Photo by Emma Schartz.

GOLDEN: Yes, and how she saw things.

RINGLE: Exactly. She gave this lecture at the Jamaica Art Center for an anniversary of the workshop. Mavis held back a bit, because everybody else on the panel said she was older and that she needed to speak less. So at the end she was like, “You know, I love the workshop, but I think we need more community. And I’ve been trying to make more community.” And Bob said, “Yes, Mavis does this all the time. Last night after the convening, I was at home and I was eating dinner, and my cousin called me and said, ‘I’m at Mavis’. Come down. She’s having a party.’” And he said she does this all the time, every weekend. Her place was the place. She had this loft in Chelsea and she was always cooking something with cabbage. She was a vegetarian. She was growing her own food in the bathtub. She was extremely social, but it was really important to have a community around her. It’s also no coincidence that she got all these teaching jobs everywhere. It was through the connections that she had and that she created for herself.

GOLDEN: Right. That’s what I have felt getting to spend time with the work. I think it’s important, and I am convinced that visitors to this exhibition will see how the profound spirit of this artist is so evident in the work, in its strength, in its breadth, in its beauty. You feel the way in which she not only envisioned an artistic path for herself, but a place in the world. What’s so exciting to me, now that we’re finally having this exhibition happen, is the ability to honor who she was and what she accomplished.

Personante, n.d. Oil on canvas, 53 1/2 x 75 inches. Private collection.

SCHARTZ: My wrap-up question comes from this essay by Hilton Als that I live by. It talks about artists being a ghost in the sunlight, that idea of spirit and really having to bring memory into the living and how past and present are constantly blurred. After spending so much time with Mavis’ work, do you feel like the show brings her back into the light? What part of her glows brightest in this show, would you say?

GOLDEN: I think what this does is it really captures the true power of her spirit. The opportunity to present an exhibition means that we’re not only getting the chance to see what she did through her work, but also all the space that it opened up for so many other artists, some of whom might not have known her work. In some ways, this exhibition is about opening up and expanding what has been, by many people, a complete love for her and for her work. Hallie?

RINGLE: Oh, man. We did a conversation about music with Chief Xian aTunde Adjuah a while ago. He said he saw a print of hers and said, “I’ve never seen music until I saw this print.” And I thought, “That’s it. That’s her.” You know?

GOLDEN: Mm-hmm.

RINGLE: She’s alive.

GOLDEN: We see it and we can feel it. The work has such profound spirit in it, and the exhibition is a way to really honor that spirit.

Installation view of Mobile Images. Institute of Contemporary Art, University of Pennsylvania. Photographed by Constance Mensch.

SCHARTZ: Are there any last things you’d like to say, to shout out for Mavis and for people in New York City and across the country to go see this exhibition?

GOLDEN: We hope that everyone will go to the ICA Philadelphia and see this exhibition. If they can’t, we hope they’ll at least go online and see what will be some of the profoundly beautiful ways in which the exhibition’s interpreted. There is a catalog accompanying this exhibition, so it’s another way to learn more and see more of her work. And then our hope is this exhibition will be traveling. So, following the ICA and the Studio Museum, it will allow people who are not in either of these places to have a chance to encounter the exhibition.

RINGLE: We hope this is the beginning of deep, deep engagement with Mavis on many levels.