RECLINE & LUXURIATE

Mickalene Thomas and Whoopi Goldberg on Artistic Freedom

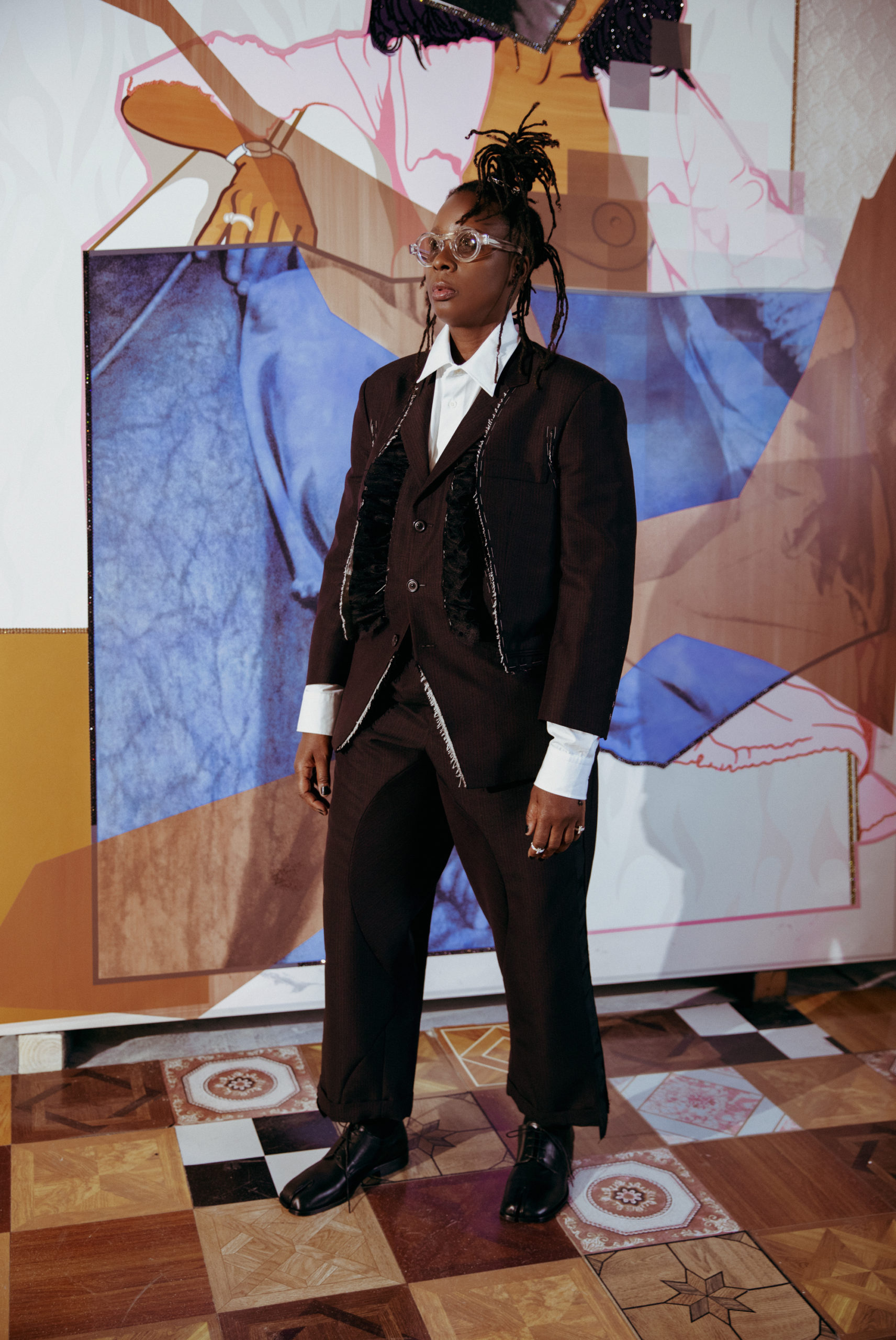

Jacket and Pants by Issey Miyake Homme Plissé. Shirt by Gucci. Sunglasses and Bracelet Mickalene’s Own. Necklace (worn in hair) and Rings by L’Enchanteur. Socks Stylist’s Own. Shoes by Loewe.

This fall, Mickalene Thomas is taking over the world. The 50-year-old Brooklyn-based artist is launching the kind of global tour more in keeping with rock stars, kicking off her four-city Lévy Gorvy gallery mega-exhibition in New York with large-scale paintings based on Black women who appeared in the vintage pages of Jet magazine. Then she’s off to London, Paris, and Hong Kong to unveil three new series of works. The title of this globe-trotting extravaganza? Beyond the Pleasure Principle, a mashup of Janet Jackson (see her 1986 hit pop song) and Sigmund Freud (see his 1920 foundational essay). As if that weren’t enough, the artist has her first, career-spanning monograph out from Phaidon this fall. Thomas spoke with one of her idols from her studio as the paint was still drying.

———

WHOOPI GOLDBERG: I’m a big fan of your work. Where are you right now?

MICKALENE THOMAS: I’m in Brooklyn, close to the Navy Yard. Where Spike Lee and all those Black bohemians used to be. I’m just floored to be talking to you. I have to say, you’ve inspired my personal and professional life. I remember your comedy performance in 1984 where you were wearing a white shirt on your head and calling it your “long, luxurious blond hair,” which changed everything for me—and not just for me, but I’m sure for a lot of Black and Brown kids who look like us. I used a little clip of that in one of my videos called “Do I Look Like a Lady?,” the arc of which is about Black female singers, comedians, and celebrities and how they project and personify beauty and their understanding of what that means in the world.

GOLDBERG: We as Black women always have to deal with the comparison, even with each other, of, “Am I ever going to look good enough to be XYZ?”

THOMAS: Exactly. And I’ve learned to appreciate it. I don’t want to look like anyone else. I started having my locks in braids at a very young age and people would say, “Oh, Whoopi!” At first, I didn’t know what that meant. But when I realized who Whoopi was, I was like, “I embrace that. She’s powerful. She’s smart. She’s beautiful. She’s funny. She’s intelligent. Yeah, I’m Whoopi.”

GOLDBERG: I love that, because the whole point of that show was to say, “Listen, there are so many roadblocks that I can’t even keep up. So this is what you get.” Let me ask you, as an artist, how do you see beauty? Do you see it through the eyes of women? Is it through the eyes of Black women? Is it through a brush or the camera? How do you perceive it?

THOMAS: I perceive beauty in a myriad of ways, and I think it has to do with experience. It started for me at home, growing up, looking at my mother and my grandmother and how they saw themselves. They never allowed who they were or how they were perceived to be an obstacle. It was never age or color that prevented them from doing anything. So I see beauty as a perseverance and resilience in a person. It’s definitely something that exudes from the inside out. It’s how you’re a magnet and how you attract things in your life.

GOLDBERG: When I was little, people would say, “Beauty is skin deep.” And I never could figure out what that meant, because as a kid, I had a mom like you. She was who she was, and if you didn’t get it or didn’t like it, it wasn’t her problem. Her attitude with me was, no one will get who and what you are. They’re just not going to, because you resonate in a different way. So they’re not going to say to you, “My god, you stop traffic!” But, if they get to know you, they may say that. That felt like a kind of freedom when I got older. I was lucky to have a mother who said, “Divine is on the inside.”

THOMAS: My mother was 6’1″ and gorgeous. She modeled. I look more like her now, but growing up I didn’t. So people were saying, “That’s your daughter?” My mother had a very exquisite beauty, with these high cheekbones, but I didn’t have that growing up. I didn’t feel ugly, I just felt different. All I knew was that I did not look like my mother, but I wanted to. She taught me resilience, and to not rely on the outside world to define who you are.

GOLDBERG: That’s the message a lot of us got from the women in our lives. The women who would say, “Nobody can tell you who you are and that this is how you have to be.” It’s a great thing, but it’s been a pain in the ass as well, because it doesn’t let me be very flexible when people try to tell me things. Now, you were born an artist. How old were you when it began to manifest?

THOMAS: I grew up in Newark, New Jersey, and we would come to New York to visit the museums, but it wasn’t until my early twenties that I really gravitated towards a creative practice, and that was when I was living in Portland, Oregon. I’d moved out there right after high school with my partner at the time. The percentage of Black people in Portland is very small, but I found a community of artists and musicians that I surrounded myself with and who really inspired me. It was the right moment. I was just coming into myself, and I started making art. I had also seen an incredible exhibit by Carrie Mae Weems at the Portland Art Museum, and that spearheaded this newfound trajectory for me. It was the first time I saw contemporary art in a museum that reflected who I was. That was the moment that I knew I wanted to become an artist. So I decided to go to art school, which was a strange concept in my family. No one really knew what that meant. They were like, “You’re not going to make any money.” As Black folks, you want security.

Top by Dylan Mekhi. Shirt by Issey Miyake Homme Plissé. Pants Stylist’s Own. Sunglasses by Selima Optique. Earrings (worn in hair), Bracelet, and Rings (worn on right hand) by Bvlgari. Socks by Falke. Shoes by Christian Louboutin.

GOLDBERG: I realized at a later age that all anybody wants you to do is not ask them for money. Do you consider yourself a performance artist?

THOMAS: There are definitely some performative elements in my work, and I have performed. The other performative elements are the environments that I create for my sitters, and I like to think of those as collaborative. But whether it’s me using myself as the subject or working with other sitters or models, it’s performative.

GOLDBERG: Are you a Black artist, or are you an artist?

THOMAS: That’s a great question. It’s funny because I’ve been doing the press release for my upcoming show and there’s a sentence where it says, “Black queer artist,” and then, a little later, “queer Black artist.” Black artists so often have to define ourselves based on how we look. We don’t have the same freedom or privilege as white people to walk around and say, “I’m an artist.” And I welcome that. There was a time when I shied away from it. To be quite honest, Whoopi, there were times when I was like, “Don’t say I’m a Black artist. I’m an artist.” But I think there’s a power in stating or defining a position. And I got that primarily from Kerry James Marshall, who unapologetically speaks about being a Black artist. Once I learned that from him, I decided to take it on. That’s why I continue to make images with Black women at the center.

GOLDBERG: When Oprah saw the painting you did of her, what was her reaction?

THOMAS: I’ve never met Oprah. The images for that series were archival. But she did see them, because my first show was in Chicago, where her network and studio are. I got a note back that said, “She did a good job making me look good.” But I would love to photograph her. It’s on my bucket list.

GOLDBERG: You also did Condoleezza [Rice] in that same series. What made you want to portray her?

THOMAS: It was more about the dualty of the two. They were polar opposites at the particular time when Condoleezza Rice was in the news. She and Oprah represented a particular Black woman in power, but they were perceived very differently by the public. I called that series “When Ends Meet,” as if they were coming together as Black women. They both did amazing things. I can see the positivity they represent for many women and for girls that look like us who probably want to go into those fields. It was about celebrating these two forces.

GOLDBERG: Your work always feels like a celebration. This is us. Here we be.

THOMAS: People tend to shy away from sexuality and create respectability politics around how we’re supposed to be and talk and walk. We don’t have the freedom of just luxuriating or just being. That’s why, compositionally, I like to put Black women in the same positions as the subjects in Old Master paintings, because it’s about having that freedom to just be in the moment, to recline without doing work. Can’t we just recline? Can’t we have that moment of being looked at without having to have all of this baggage? Can’t we luxuriate?

GOLDBERG: We’re held to a different standard. We’re not allowed to just sit down. It is habitual for people to expect us to be in continuous motion. Speaking of which, do you work on multiple projects at the same time?

THOMAS: Yes. Right now I’m doing several different bodies of work. One is paintings about Jet magazine; another is a series of portraits related to Picasso; another is called “Resist,” that’s using archival images from the media, from 1960s Civil Rights to the present-day Black Lives Matter [movement]; and then I’m working on two videos; and we’re also doing some special projects and sculptures.

Blazer, Pants, and Shoes by Maison Margiela. Shirt by Hermès. Sunglasses by Selima Optique. Rings by Tiffany & Co. Socks by Falke.

GOLDBERG: You once did a portrait of Donna Summer. Is she an inspiration for you?

THOMAS: Oh, yeah. Her album Once Upon a Time is so cool. She’s a creative force that shifted the music industry even though she was under-appreciated.

GOLDBERG: Donna was a friend of mine, and she was everything you want Donna Summer to be—and more. She embodied the idea that nobody could stop you. If you had your groove, that was your groove. Let me ask you, there have been a lot of strides made in the art world with embracing new voices, and especially people of color. Do you think that’s something we’re always going to have to monitor?

THOMAS: Always. The art world is very complicated. It’s a billion-dollar market and many people don’t understand how it works. But with Black people entering it, not just showing their work, but also collecting, it’s going to be quite a change. I do have some Brown and Black collectors, but it’s a very small percentage. Most of my collectors are white or Asian. There need to be more Black people owning and running galleries. It’s not just about being artists. We’re already doing that. It’s about moving into other areas that are going to become fundamental to our growth and to really hold onto it because otherwise, this time is going to be fleeting. We might not be at this same moment 10 years from now unless we have people writing about our work and putting on shows and collecting us. We need Black people collecting art like they’re collecting their Rolexes.

GOLDBERG: How do we get that?

THOMAS: I don’t think many Black people understand the value of art. It increases, unlike boats and cars that depreciate once you buy them. And it’s a great investment in our cultural history. We have to get to a point where people support contemporary artists, collecting and buying the work and not putting their nose up at particular price points.

GOLDBERG: Everybody wants you to get your due but nobody wants to give it to you.

THOMAS: Exactly. I have a sign on the door of my studio that says, “Do not ask for discounts when purchasing art.”

GOLDBERG: Do people do that?

THOMAS: Yes!

GOLDBERG: Does fame help or hurt an artist?

THOMAS: It depends on the artist. I don’t necessarily see myself as a famous person, but I guess I have a name that people recognize. So I think it’s how you get up in the morning. If you’re going to walk out into the world and be the type of person that has a big ego, no. But fame can be fleeting. I don’t walk around as if I’m famous. I still live in the same neighborhood I lived in when I started undergrad. If I consider myself famous then I’m detaching myself from other people in the world who I can no longer have access to, and I love being around everyday people who inspire me. But I’m also conscientious and know that what I do can create change and opportunities for others. And because of my success, I’m able to do things that other people aren’t able to do and I use that in ways that are uplifting and inspiring to those who aren’t at that position. My partner and I have created various advocacies and platforms for artists of color and queer artists, supporting them financially, helping them with their exhibitions, curating, and advising them on contracts. So I try to pay it forward.

GOLDBERG: Well, I think you’re more than famous. You’re successful. However you’re defining it, it’s coming with a big smile.

THOMAS: Maya Angelou talked about the idea that how you make people feel is the mark you’ll leave behind. And that’s what I keep. It’s not about what you say, it’s about how you make people feel.

———

Hair: Laila Hayani using Andis at Forward Artists.

Makeup: Dick Page at Statement Artists.

Set Design: Jenny Correa at Art Department.